Effectiveness of a Nature Sports Program on Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

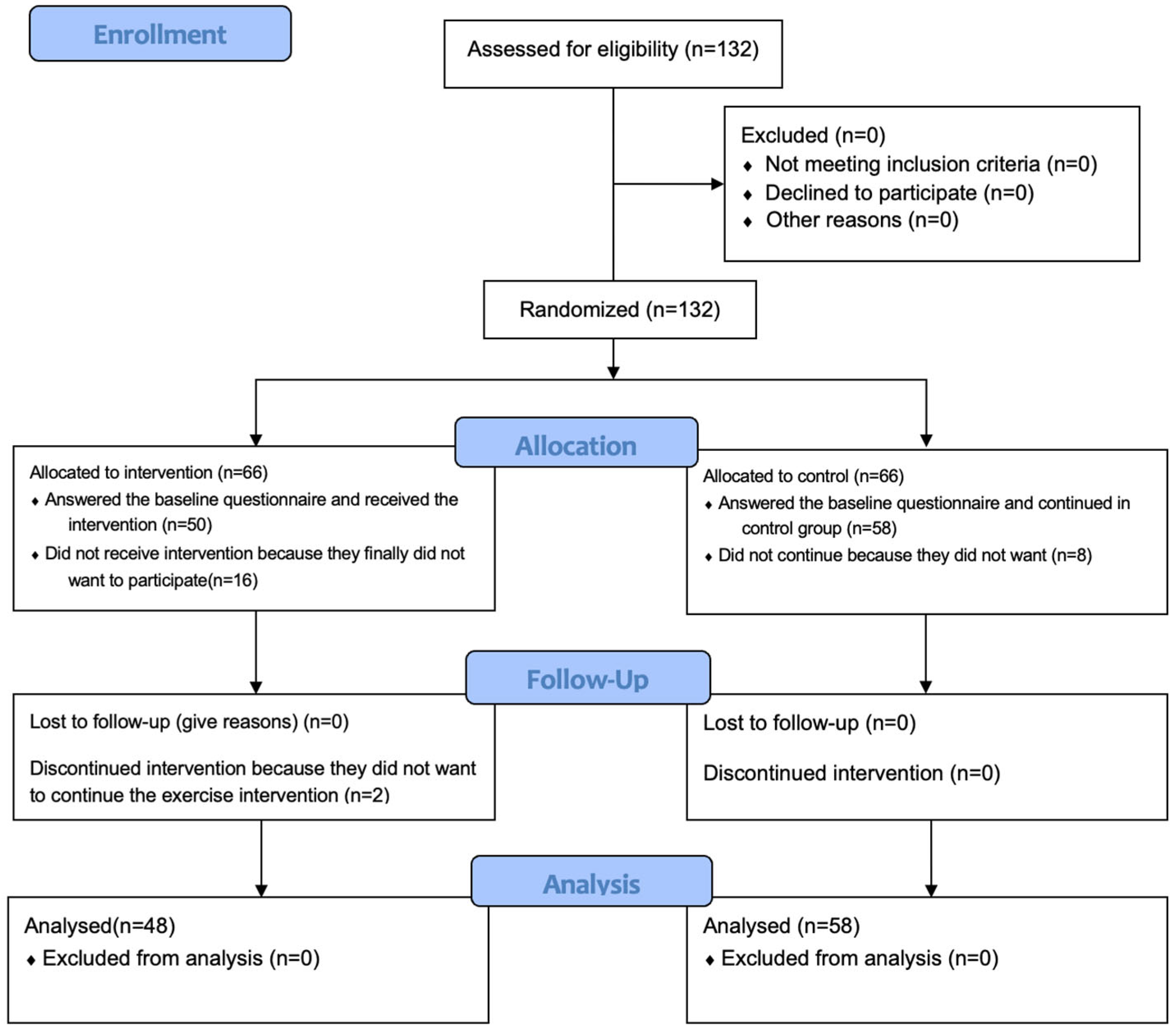

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Randomization

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Study Variables and Data Collection

2.6. Blinding

2.7. Statistical and Qualitative Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

Post-Intervention Scores

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of This Study and Future Research

4.2. Strengths of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Control group |

| IG | Intervention group |

References

- Online Etymology Dictionary. Burnout. Available online: https://www.etymonline.com/word/burn-out (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Schwartz, M.S.; Will, G.T. Low morale and mutual withdrawal on a hospital ward. Psychiatry 1953, 16, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, H.B. Community-based treatment for young adult offenders. Crime Delinq. 1969, 15, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff burn-out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. Maslach Burnout Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisdedos, N. Maslach Burnout Inventory (Spanish Adaptation); TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Constitution of the World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031029 (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; de Andrade, S.M. Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, T.; Ho, R.; Tang, A.; Tam, W. Global prevalence of burnout symptoms among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 123, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Vu, T.H.T.; Fuller, J.A.; Freedman, M.; Bannon, J.; Wilkins, J.T.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Hirschhorn, L.R.; Wallia, A.; Evans, C.T. The association of burnout with work absenteeism and the frequency of thoughts in leaving their job in a cohort of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Health Serv. 2023, 3, 1272285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, C.L.; Abreu, L.C.; Ramos, J.L.S.; Castro, C.F.D.; Smiderle, F.R.N.; Santos, J.A.D.; Bezerra, I.M.P. Influence of burnout on patient safety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina 2019, 55, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Albendín-García, L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Romero-Bejar, J.L.; De la Fuente-Solana, E.I.; Cañadas, G.R. Analyzing latent burnout profiles in a sample of Spanish nursing and psychology undergraduates. Healthcare 2024, 12, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Velando-Soriano, A.; Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Ramírez-Baena, L.; Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Ortega-Campos, E.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Prevalence and levels of burnout in nursing students: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2023, 72, 103753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, Y. Psychological mechanisms of healthy lifestyle and academic burnout: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1533693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.E.; Bird, M.D.; Jackman, P.C. Comparing the effects of affect-regulated green and indoor exercise on psychological distress and enjoyment in university undergraduate students: A pilot study. J. Adv. Sport Psychol. Res. 2022, 2, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 388, e081124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Tian, X.; Wu, H. Exploring the mediating role of social support in sports participation and academic burnout among adolescent students in China. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1591460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, Y.A.; AbdulJabbar, M.A.; Ali, O.A. The effect of sports job burnout on the performance of workers in student activities departments in Iraqi universities. Retos 2025, 66, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Ricardo, Y.; Caiza, M.V.; Sánchez-Cañizares, M.; Ferreira, J.P. Physical exercise, burnout syndrome levels and heart rate variability in university students. Medicina 2021, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Liu, F.; Mou, L.; Zhao, P.; Guo, L. How physical exercise impacts academic burnout in college students: The mediating effects of self-efficacy and resilience. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 964169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M. Burnout among Iranian medical students: Prevalence and its relationship to personality dimensions and physical activity. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2021, 1, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Pinto, A.M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresó, E.; Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. In search of the “third dimension” of burnout: Efficacy or inefficacy? Appl. Psychol. 2007, 56, 460–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunston, E.R.; Messina, E.S.; Coelho, A.J.; Chriest, S.N.; Waldrip, M.P.; Vahk, A.; Taylor, K. Physical activity is associated with grit and resilience in college students: Is intensity the key to success? J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castillo, A.; Fernández-Prados, M.J. Resilience and burnout in educational science university students: Developmental analysis according to progression in the career. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 4293–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, C.; Mack, D.E.; Wilson, P.M. Does physical activity in natural outdoor environments improve wellbeing? A meta-analysis. Sports 2022, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, S.A.; Aidman, E.; Teychenne, M.; Smith, J.J.; Swann, C.; Rosenbaum, S.; White, R.L.; Lubans, D.R. Optimising the effects of physical activity on mental health and wellbeing: A joint consensus statement from Sports Medicine Australia and the Australian Psychological Society. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2023, 26, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C. Awareness of healthy life and mental health of nursing college students before and after the COVID-19 outbreak with the involvement in sports activities. Rev. Psicol. Deporte (J. Sport Psychol.) 2024, 33, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, C.; Meixner, F.; Wiebking, C.; Gilg, V. Regular physical activity, short-term exercise, mental health, and well-being among university students: The results of an online and a laboratory study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 388, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Mean (Standard Deviation) | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | CG: 22.28 (7.87) IG: 21.24 (1.83) | 12.951 | 0.332 | |

| Working hours per week | CG: 3.7 (12.22) IG: 3.65 (12.22) | 0.311 | 0.982 | |

| Mean steps per day | CG: 7912.04 (1150.88) IG: 8237.64 (1284.77) | 0.986 | 0.171 | |

| Emotional exhaustion | CG: 14.86 (7.76) IG: 12.44 (7.28) | 0.259 | 0.083 | |

| Cynicism | CG: 4.06 (4.13) IG: 4.55 (5.08) | 1.151 | 0.587 | |

| Academic efficacy | CG: 26.54 (5.42) IG: 23.68 (9.20) | 16.381 | 0.057 | |

| Stress | CG: 18.76 (6.75) IG: 18.44 (7.08) | 0.024 | 0.816 | |

| Anxiety | CG: 9.46 (3.42) IG: 9.28 (3.79) | 0.820 | 0.793 | |

| Depression | CG: 12.28 (1.96) IG: 12.65 (2.54) | 2.401 | 0.063 | |

| Engagement | CG: 3.96 (1.18) IG: 3.50 (1.54) | 2.912 | 0.073 | |

| Categorical variables | Group | Categories % | Chi-squared | p |

| Sex | CG | Male: 16% Female: 84% | 1.09 | 0.295 |

| IG | Male: 24.4% Female: 75.86% | |||

| Marital Status | CG | Single: 90% Married: 10% | 96.70 | <0.001 |

| IG | Single: 94.82% Married: 5.18% | |||

| Children | CG | No: 94% | 3.57 | 0.167 |

| IG | No: 98.04% | |||

| Working and studying | CG | Yes: 12% | 1.46 | 0.227 |

| IG | Yes: 20.64% | |||

| Emotional exhaustion | CG | Low (50%), medium (16%), high (34%) | 2.66 | 0.264 |

| IG | Low (63.64%), medium (15.48%), high (20.64%) | |||

| Cynicism | CG | Low (74%), medium (22%), high (4%%) | 0.448 | 0.799 |

| IG | Low (70.52%), medium (22.36%), high (6.88%) | |||

| Academic efficacy | CG | High (44%), medium (34%), low (22%) | 2.76 | 0.252 |

| IG | High (43%), medium (22.36%), low (34.4%) | |||

| Burnout | CG | 46% | 3.72 | 0.444 |

| IG | 37.84% |

| Variable | Mean (Standard Deviation) | t | Cohen’s D (95%CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | GC: 17.24 (7.31) IG: 13.96 (6.39) | 2.23 | 0.483 (0.05, 0.91) | 0.028 |

| Cynicism | CG:5.29 (5.43) | −0.28 | −0.061 (−0.48, 0.36) | 0.779 |

| IG: 5.60 (4.84) | ||||

| Professional efficiency | CG: 26.05 (4.69) | 0.699 | 0.151 (−0.27, 0.57) | 0.486 |

| IG: 25.15 (6.69) | ||||

| Stress | CG: 20.35 (7.25) IG: 17.50 (5.36) | 2.11 | 0.456 (0.02, 0.88) | 0.037 |

| Anxiety | CG: 9.59 (2.76) IG: 9.28 (3.79) | 0.46 | 0.101 (0.10, −0.32) | 0.641 |

| Depression | CG: 11.97 (2.51) IG: 11.39 (2.87) | 1.06 | 0.229 (0.22, −0.19) | 0.291 |

| Engagement | CG: 4.04 (1.04) IG: 4.06 (1.13) | −0.10 | −0.22 (−0.44, 0.40) | 0.920 |

| Average steps per day | CG: 8573 (1337.22) IG: 9954.55 (1204.85) | −5.06 | −1.09 (−1.54, −0.63) | <0.001 |

| Variable | Mean (Standard Deviation) | Effect | F | Partial η2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional exhaustion | CG pre: 14.86 (7.76) CG post: 17.24 (7.31) IG pre: 12.44 (7.28) IG post: 13.96 (6.39) | Time | 5.85 | 0.056 | 0.017 |

| Group | 16.28 | 0.141 | <0.001 | ||

| Time * group | 0.002 | 0.00 | 0.967 | ||

| Cynicism | CG pre: 4.06 (4.13) CG post: 5.29 (5.43) IG pre: 4.55 (5.08) IG post: 5.60 (4.84) | Time | 3.36 | 0.031 | 0.070 |

| Group | 0.34 | 0.003 | 0.561 | ||

| Time * group | 0.02 | 0.000 | 0.881 | ||

| Professional efficiency | CG pre: 26.54 (5.42) CG post: 26.05 (4.69) IG pre: 23.68 (9.20) IG post: 25.15 (6.69) | Time | 1.09 | 0.013 | 0.3 |

| Group | 2.37 | 0.027 | 0.128 | ||

| Time * group | 0.66 | 0.008 | 0.42 | ||

| Stress | CG pre: 18.76 (6.75) CG post: 20.35 (7.25) IG pre: 18.44 (7.08) IG post: 17.50 (5.36) | Time | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.852 |

| Group | 5.31 | 0.058 | 0.024 | ||

| Time * group | 0.45 | 0.005 | 0.505 | ||

| Anxiety | CG pre: 9.46 (3.42) CG post: 9.59 (2.76) IG pre: 9.28 (3.79) IG post: 9.27 (3.36) | Time | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.985 |

| Group | 1.03 | 0.016 | 0.314 | ||

| Time * group | 0.68 | 0.011 | 0.414 | ||

| Depression | CG pre: 12.28 (1.96) CG post: 11.97 (2.51) IG pre: 12.65 (2.54) IG post: 11.39 (2.87) | Time | 4.98 | 0.055 | 0.028 |

| Group | 0.30 | 0.003 | 0.584 | ||

| Time * group | 1.47 | 0.017 | 0.228 | ||

| Engagement | CG pre: 3.96 (1.18) CG post: 4.04 (1.04) IG pre: 3.50 (1.54) IG post: 4.06 (1.13) | Time | 3.34 | 0.037 | 0.071 |

| Group | 0.70 | 0.008 | 0.406 | ||

| Time * group | 0.86 | 0.010 | 0.355 | ||

| Average steps per day | CG pre: 7912.04 (1150.88) CG post: 8573 (1337.22) IG pre: 8237.64 (1284.77) IG post: 9954.55 (1204.85) | Time | 45.32 | 0.304 | <0.001 |

| Group | 28.18 | 0.213 | <0.001 | ||

| Time * group | 9.41 | 0.083 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Conde, I.; Suleiman-Martos, N.; Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Lazo-Caparros, M.D.; García-Oliva, S.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Effectiveness of a Nature Sports Program on Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Clinical Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192510

Pérez-Conde I, Suleiman-Martos N, Membrive-Jiménez MJ, Lazo-Caparros MD, García-Oliva S, Cañadas-De la Fuente GA, Gómez-Urquiza JL. Effectiveness of a Nature Sports Program on Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Clinical Trial. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192510

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Conde, Inmaculada, Nora Suleiman-Martos, María José Membrive-Jiménez, María Dolores Lazo-Caparros, Sofía García-Oliva, Guillermo A. Cañadas-De la Fuente, and Jose Luis Gómez-Urquiza. 2025. "Effectiveness of a Nature Sports Program on Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Clinical Trial" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192510

APA StylePérez-Conde, I., Suleiman-Martos, N., Membrive-Jiménez, M. J., Lazo-Caparros, M. D., García-Oliva, S., Cañadas-De la Fuente, G. A., & Gómez-Urquiza, J. L. (2025). Effectiveness of a Nature Sports Program on Burnout Among Nursing Students: A Clinical Trial. Healthcare, 13(19), 2510. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192510