Evaluating the Perceptions, Expectations, and Concerns of Community Pharmacists in Germany Regarding Prescribing by Pharmacists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire Development

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Ethical Issues

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Recommendations for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMP | Non-medical prescribing |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| IP | Independent prescriber |

| CPs | Community pharmacists |

| OTC | Over-the-counter |

| GP | General practitioner |

| PSA | Prescribing safety assessment |

References

- World Health Organization. Quality of Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Stewart, D.; Jebara, T.; Cunningham, S.; Awaisu, A.; Pallivalapila, A.; MacLure, K. Future perspectives on nonmedical prescribing. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2017, 8, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpola, R.L.; Issakhany, D.; Gisev, N.; Hopkins, R.E. The accessibility of pharmacist prescribing and impacts on medicines access: A systematic review. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2024, 20, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, L.C.; Abuzour, A.S.; Tully, M.P. Nonmedical prescribing: Where are we now? Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2016, 7, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham-Clarke, E.; Rushton, A.; Noblet, T.; Marriott, J. Non-medical prescribing in the United Kingdom National Health Service: A systematic policy review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crown, J. Review of Prescribing, Supply & Administration of Medicines—Final Report; UK Government Web Archive: London, UK, 1999. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20130105143320mp_/http:/www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_4077153.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Thyer, A.; Robinson, P. MLX 284—Proposals for Supplementary Prescribing by Nurses and Pharmacists and Proposed Amendments to the Prescription Only Medicines (Human Use) Order 1997; UK Government Web Archive: London, UK, 2002. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20150113190110mp_/http:/www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/comms-ic/documents/websiteresources/con2022567.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Medicines & Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. MLX 321—Consultation on Proposals to Introduce Independent Prescribing by Pharmacists; Medicines & Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency: London, UK, 2005. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20141008042455mp_/http:/www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/comms-ic/documents/websiteresources/con007684.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- NHS England. Pharmacy First. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/pharmacy-services/pharmacy-first/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- UK Government Department of Health and Social Care Media Centre. Pharmacy First: What You Need to Know. 2024. Available online: https://healthmedia.blog.gov.uk/2024/02/01/pharmacy-first-what-you-need-to-know/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Karim, L.; McIntosh, T.; Jebara, T.; Pfleger, D.; Osprey, A.; Cunningham, S. Investigating practice integration of independent prescribing by community pharmacists using normalization process theory: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2024, 46, 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancarz, K. Pharmacists Prescribing in Poland; Polish Pharmaceutical Chamber: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; Available online: https://www.nia.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Pharmacist-prescribing-Katarzyna-Gancarz-Polish-Pharmacutical-Chamber.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Owczarek, A.; Marciniak, D.M.; Jezior, R.; Karolewicz, B. Assessment of the prescribing pharmacist’s role in supporting access to prescription-only medicines—Metadata analysis in Poland. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszewska, J.; Wrzosek, N.; Zimmermann, A. Extended prescribing roles for pharmacists in Poland—A survey study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins English Dictionary. Available online: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/repeat-prescription (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Ghabour, M.; Morris, C.; Wilby, K.J.; Smith, A.J. Pharmacist prescribing training models in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada: Snapshot survey. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 23, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for the Initial Education and Training of Pharmacists; General Pharmaceutical Council: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://assets.pharmacyregulation.org/files/2024-01/Standards%20for%20the%20initial%20education%20and%20training%20of%20pharmacists%20January%202021%20final%20v1.4.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Dixon, D.L.; Johnston, K.; Patterson, J.; Marra, C.A.; Tsuyuki, R.T. Cost-effectiveness of pharmacist prescribing for managing hypertension in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2341408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafferty, E.; Yaghoubi, M.; Taylor, J.; Farag, M. Costs and savings associated with a pharmacists prescribing for minor ailments program in Saskatchewan. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2017, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.F.; Maskrey, M.; MacBride-Stewart, S.; Lees, A.; Macdonald, H.; Thompson, A. New ways of working releasing general practitioner capacity with pharmacy prescribing support: A cost-consequence analysis. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebara, T.; Cunningham, S.; MacLure, K.; Awaisu, A.; Pallivalapila, A.; Stewart, D. Stakeholders’ views and experiences of pharmacist prescribing: A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1883–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, K.; Byrne, S. Role of the pharmacist in reducing healthcare costs: Current insights. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2017, 6, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Teichert, U.; van den Bussche, H. Ärztemangel in der hausärztlichen Versorgung auf dem Lande und im Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienst. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz 2018, 61, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker, S.; Joshi, R.; Shanthosh, J.; Ma, C.; Webster, R. Non-Medical prescribing policies: A global scoping review. Health Policy 2020, 124, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A. Non-medical prescribing in primary care in the UK: An overview of the current literature. J. Prescr. Pract. 2023, 5, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J.K. A prescription for better prescribing. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 61, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauld, N.J. Analysing the landscape for prescription to non-prescription reclassification (switch) in Germany: An interview study of committee members and stakeholders. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.; MacLure, K.; George, J. Educating nonmedical prescribers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 74, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Nurses Association. Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN). Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/aprn/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Royal College of Surgeons of England. Advanced Nurse Practitioner. Available online: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/careers-in-surgery/surgical-team-hub/surgical-team-roles/advanced-nurse-practitioners/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Bundesgesundheitsministerium. Kurzpapier: Vorläufige Eckpunkte Pflegekompetenzgesetz; Bundesgesundheitsministerium: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/P/Pflegekompetenzreform/Kurzpapier_Vorlaeufige_Eckpunkte_PflegekompetenzG.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände. Die Apotheke—Zahlen, Daten, Fakten 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/ZDF/ABDA_ZDF_2023.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Bundesministerium der Justiz. Apothekenbetriebsordnung in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 26. September 1995 (BGBl. I S. 1195), die Zuletzt Durch Artikel 8z4 des Gesetzes vom 12. Dezember 2023 (BGBl. 2023 I Nr. 359) Geändert Worden Ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/apobetro_1987/BJNR005470987.html (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Bundesgesetzblatt im Internet. Gesetz zur Stärkung der Vor-Ort-Apotheken. 2020. Available online: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Gesetze_und_Verordnungen/GuV/S/Gesetz_zur_Staerkung_der_Vor_Ort_Apotheken.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Bundesministerium der Justiz. Apothekengesetz in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 15. Oktober 1980 (BGBl. I S. 1993), das zuletzt durch Artikel 3 des Gesetzes vom 19. Juli 2023 (BGBl. 2023 I Nr. 197) Geändert Worden Ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/apog/ApoG.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände. In Eine Gesunde Zukunft mit der Apotheke. 2025. Available online: https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/Pressetermine/2025/Pk_20250409_forsa-Umfrage/Positionspapier_In_eine_gesunde_Zukunft_mit_der_Apotheke_2025.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände. Positionspapier Runder Tisch—Novellierung der Approbationsordnung. 2022. Available online: https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/Ausbildung_Studium_Beruf/AAppO_Runder_Tisch_22_06_29.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Straub, B.; Germans are losing faith in their healthcare policy. Robert Bosch Stiftung, 27 March 2023. Available online: https://www.bosch-stiftung.de/en/storys/germans-are-losing-faith-their-healthcare-policy (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Greiner, G.G.; Schwettmann, L.; Goebel, J.; Maier, W. Primary care in Germany: Access and utilisation—A cross-sectional study with data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefert, J.; Zimmermann, N.; Thakkar, K.; Mészáros, Á. Pharmacy customers’ views towards the potential introduction of pharmacist prescribing: A survey study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Pharmacological Society. Ten Principles of Good Prescribing. Available online: https://www.bps.ac.uk/education-engagement/teaching-pharmacology/ten-principles-of-good-prescribing (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- LimeSurvey. Privacy Notice. Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org/privacy-notice (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände. Die Apotheke—Zahlen, Daten, Fakten 2024; Bundesvereinigung Deutscher Apothekerverbände: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.abda.de/fileadmin/user_upload/assets/ZDF/Zahlen-Daten-Fakten-24/ABDA_ZDF_2024_Broschuere.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Qualtrics. Sample Size Calculator. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/de/erlebnismanagement/marktforschung/stichprobenrechner/ (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Amador-Fernández, N.; Botnaru, I.; Allemann, S.S.; Kälin, V.; Berger, J. Clinical relevance and implementation into daily practice of pharmacist-prescribed medication for the management of minor ailments. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1256172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, M.I.; Edelman, A.B.; Skye, M.; Darney, B.G. Reasons for and experience in obtaining pharmacist prescribed contraception. Contraception 2020, 102, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.J.; Lymn, J.; Anderson, C.; Avery, A.; Bissell, P.; Guillaume, L.; Hutchinson, A.; Murphy, E.; Ratcliffe, J.; Ward, P. Learning to prescribe—pharmacists’ experiences of supplementary prescribing training in England. BMC Med. Educ. 2008, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.; Pfleger, D.; McCaig, D.; Bond, C.; Stewart, D. Independent prescribing by pharmacists: A study of the awareness, views and attitudes of Scottish community pharmacists. Pharm. World Sci. 2006, 28, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuzour, A.S.; Lewis, P.J.; Tully, M.P. Practice makes perfect: A systematic review of the expertise development of pharmacist and nurse independent prescribers in the United Kingdom. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woit, C.; Yuksel, N.; Charrois, T.L. Competence and confidence with prescribing in pharmacy and medicine: A scoping review. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 28, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A.; Stewart, D.; Craig, G.; Boyter, A.; Reid, F.; Stewart, F.; Cunningham, S.; Maxwell, S. Student and pre-registration pharmacist performance in a UK Prescribing Assessment. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, F.; Power, A.; Stewart, D.; Watson, A.; Zlotos, L.; Campbell, D.; McIntosh, T.; Maxwell, S. Piloting the United Kingdom ‘Prescribing Safety Assessment’ with pharmacist prescribers in Scotland. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium der Justiz. Bundes-Apothekerordnung in der Fassung der Bekanntmachung vom 19. Juli 1989 (BGBl. I S. 1478, 1842), die Zuletzt Durch Artikel 8 Absatz 3a des Gesetzes vom 27. September 2021 (BGBl. I S. 4530) Geändert Worden Ist. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bapo/BJNR006010968.html (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Bundesgesetzblatt. Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I Nr. 73. 2005. Available online: http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl105s3394.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Deutsches Arzt Portal. Impfungen von Apothekern Gegen das Coronavirus: Ärzte Sind Eindeutig Dagegen. 2021. Available online: https://www.deutschesarztportal.de/interaktiv/rp-newsletter/umfrageauswertungen/detail/impfungen-von-apothekern-gegen-das-coronavirus-aerzte-sind-eindeutig-dagegen (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- McIntosh, T.; Stewart, D. A qualitative study of UK pharmacy pre-registration graduates’ views and reflections on pharmacist prescribing. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2016, 24, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Desborough, J.; Parkinson, A.; Douglas, K.; McDonald, D.; Boom, K. Barriers to pharmacist prescribing: A scoping review comparing the UK, New Zealand, Canadian and Australian experiences. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 27, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Less than 30 | 67 (18.8) |

| 30–39 | 92 (25.8) |

| 40–49 | 63 (17.7) |

| 50–59 | 90 (25.3) |

| 60–69 | 39 (11.0) |

| 70 and over | 4 (1.1) |

| No answer | 1 (0.3) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 158 (44.4) |

| Female | 197 (55.3) |

| No answer | 1 (0.3) |

| Professional Status | |

| Owner of a community pharmacy | 188 (52.8) |

| Branch manager of a community pharmacy | 47 (13.2) |

| Employed pharmacist in a community pharmacy | 121 (34.0) |

| City size of the pharmacy’s location | |

| Village with less than 5000 inhabitants | 40 (11.2) |

| Small town between 5000 and 20,000 inhabitants | 108 (30.3) |

| Medium-sized city between 20,000 and 100,000 inhabitants | 91 (25.6) |

| Large city with over 100,000 inhabitants | 114 (32.0) |

| No answer | 3 (0.8) |

| Professional experience as a community pharmacist (years) | |

| Less than 5 | 87 (24.4) |

| 5–10 | 54 (15.2) |

| 10–20 | 63 (17.7) |

| More than 20 | 149 (41.9) |

| No answer | 3 (0.8) |

| Recommendation Factors | n (%) * |

|---|---|

| Taking history of current and past medical complaints, considering the limits of self-medication (type, severity and duration of symptoms and the patient’s age) | 341 (95.8) |

| Consideration of the patient’s complete medication regimen (including allergies and intolerances) | 307 (86.2) |

| Consideration of the patient’s individual needs and preferences when selecting the most suitable dosage form | 293 (82.3) |

| Consideration of patients’ health literacy (including concerns and expectations) | 196 (55.1) |

| Cost–benefit analysis of the respective preparations | 123 (34.6) |

| Benefit-risk assessment of the respective preparations | 196 (55.1) |

| Consideration of the guidelines | 171 (48.0) |

| Preferred Prescribing Models | n (%) * |

|---|---|

| Pharmacists are allowed to prescribe medications based on a predetermined clinical management plan for a medically diagnosed condition. (Mainly refers to the issuing of prescriptions for drugs for long-term therapy (repeat prescriptions).) | 296 (83.1) |

| Pharmacists are allowed to prescribe certain prescription drugs for specific illnesses or patient groups independently and without a prior medical consultation. | 103 (28.9) |

| Pharmacists are allowed to prescribe medicines without restriction, independently and without prior medical consultation. | 18 (5.1) |

| No answer. | 18 (5.1) |

| n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statements | No Answer | Do Not Agree at All | Somewhat Disagree | Neutral | Somewhat Agree | Fully Agree |

| I would trust myself to take on a prescribing role to a certain extent after acquiring the relevant additional qualifications. | 2 (0.6) | 10 (2.8) | 23 (6.5) | 30 (8.4) | 100 (28.1) | 191 (53.7) |

| As a community pharmacist, I would trust myself to make a diagnosis for minor illnesses and prescribe medication based on this. | 3 (0.8) | 13 (3.7) | 49 (13.8) | 41 (11.5) | 113 (31.7) | 137 (38.5) |

| If pharmacists are allowed to issue prescriptions for drugs for long-term therapy, patients would be more likely to have them issued by their community pharmacists (repeat prescription). | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.1) | 15 (4.2) | 37 (10.4) | 116 (32.6) | 182 (51.1) |

| I am confident that as a prescribing community pharmacist, I would prescribe as safely as my clients’ associated GP. | 5 (1.4) | 13 (3.7) | 39 (11.0) | 63 (17.7) | 110 (30.9) | 126 (35.4) |

| My clinical assessment skills would need to be enhanced before I would be allowed to prescribe medication. | 3 (0.8) | 9 (2.5) | 28 (7.9) | 48 (13.5) | 129 (36.2) | 139 (39.0) |

| I consider it a basic prerequisite for pharmacists to undergo further training in line with their prescribing authorization. | 1 (0.3) | 8 (2.2) | 14 (3.9) | 27 (7.6) | 77 (21.6) | 229 (64.3) |

| With the help of the nationwide pharmacy network and the convenience of the pharmacy location, access to prescriptions for minor illnesses or repeat prescriptions could be facilitated by prescribing community pharmacists. | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.4) | 5 (1.4) | 17 (4.8) | 100 (28.1) | 226 (63.5) |

| The introduction of prescribing pharmacists could relieve the burden on GP practices. (More time and resources for in-depth medical care of patients would be available in GP practices). | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.4) | 7 (2.0) | 30 (8.4) | 90 (25.3) | 221 (62.1) |

| Health insurance companies should cover the costs of medicines prescribed by pharmacists. (As is already the case with the existing supply of medicines). | 3 (0.8) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.3) | 6 (1.7) | 28 (7.9) | 314 (88.2) |

| The introduction of prescribing pharmacists would be a good way for the healthcare system to save money. | 8 (2.2) | 15 (4.2) | 24 (6.7) | 81 (22.8) | 84 (23.6) | 144 (40.4) |

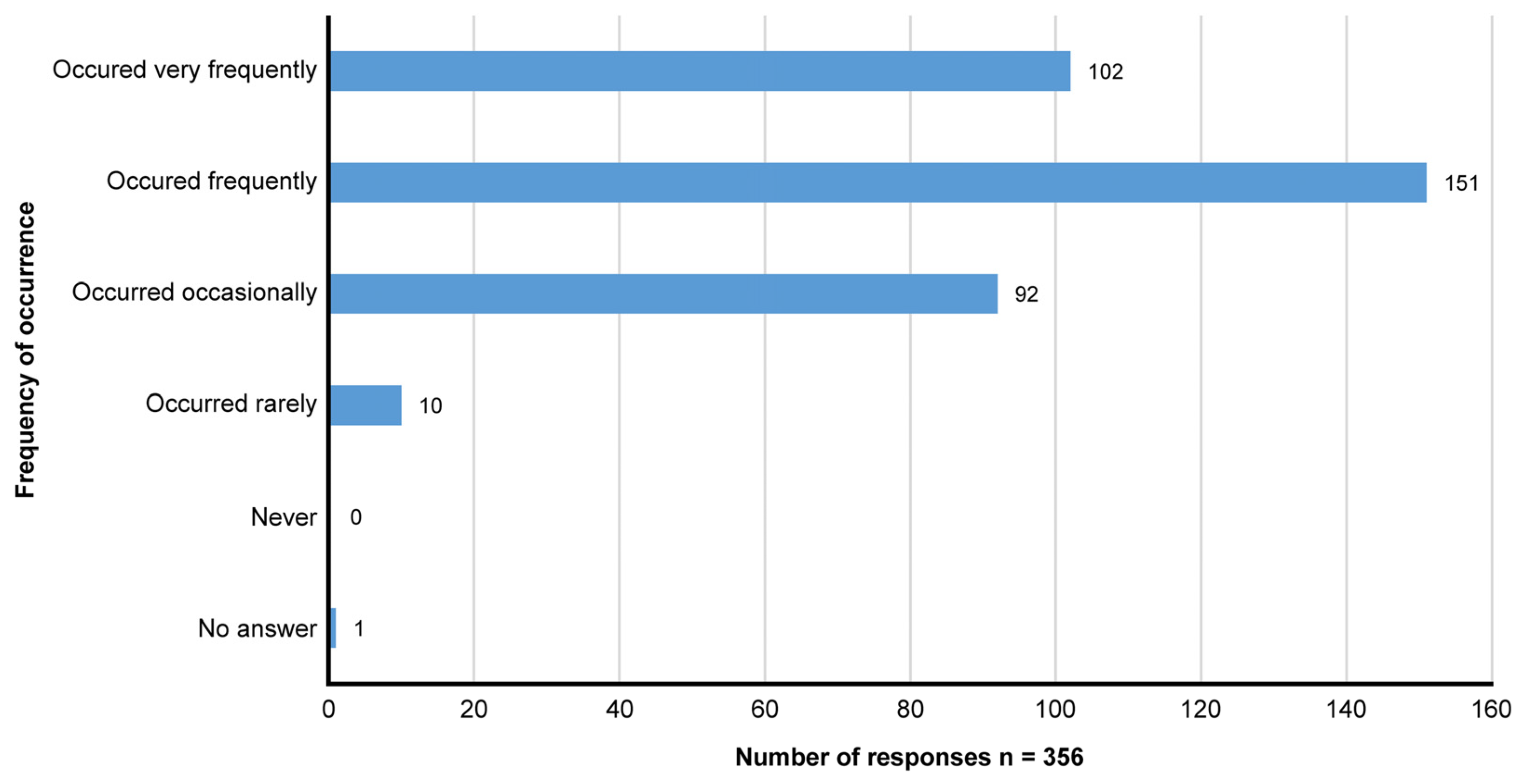

| The introduction of prescribing pharmacists could have a negative impact on patient safety. | 3 (0.8) | 98 (27.5) | 151 (42.4) | 60 (16.9) | 37 (10.4) | 7 (2.0) |

| I am of the opinion that there would be no abuse of prescriptions by the pharmacists. | 6 (1.7) | 20 (5.6) | 80 (22.5) | 88 (24.7) | 89 (25.0) | 73 (20.5) |

| I think the concept of prescribing pharmacists is a good one and I can imagine it being introduced in Germany to a certain extent. | 2 (0.6) | 15 (4.2) | 18 (5.1) | 28 (7.9) | 113 (31.7) | 180 (50.6) |

| Concerns | n (%) * |

|---|---|

| Lack of clarity about the legal framework. | 234 (65.7) |

| Additional bureaucratic effort due to delays caused by health insurance companies. | 177 (49.7) |

| The possibility of harm to the patient as a result of a misjudgment. | 140 (39.3) |

| Other | 68 (19.1) |

| The quality of care if pharmacists were allowed to prescribe independently would not correspond to that of a doctor. | 59 (16.6) |

| I have no concerns. | 57 (16.0) |

| No answer | 3 (0.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zimmermann, N.; Siefert, J.; McIntosh, T.; Mészáros, Á. Evaluating the Perceptions, Expectations, and Concerns of Community Pharmacists in Germany Regarding Prescribing by Pharmacists. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2490. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192490

Zimmermann N, Siefert J, McIntosh T, Mészáros Á. Evaluating the Perceptions, Expectations, and Concerns of Community Pharmacists in Germany Regarding Prescribing by Pharmacists. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2490. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192490

Chicago/Turabian StyleZimmermann, Niklas, Jan Siefert, Trudi McIntosh, and Ágnes Mészáros. 2025. "Evaluating the Perceptions, Expectations, and Concerns of Community Pharmacists in Germany Regarding Prescribing by Pharmacists" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2490. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192490

APA StyleZimmermann, N., Siefert, J., McIntosh, T., & Mészáros, Á. (2025). Evaluating the Perceptions, Expectations, and Concerns of Community Pharmacists in Germany Regarding Prescribing by Pharmacists. Healthcare, 13(19), 2490. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192490