Active Breaks in Primary and Secondary School Children and Adolescents: The Point of View of Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

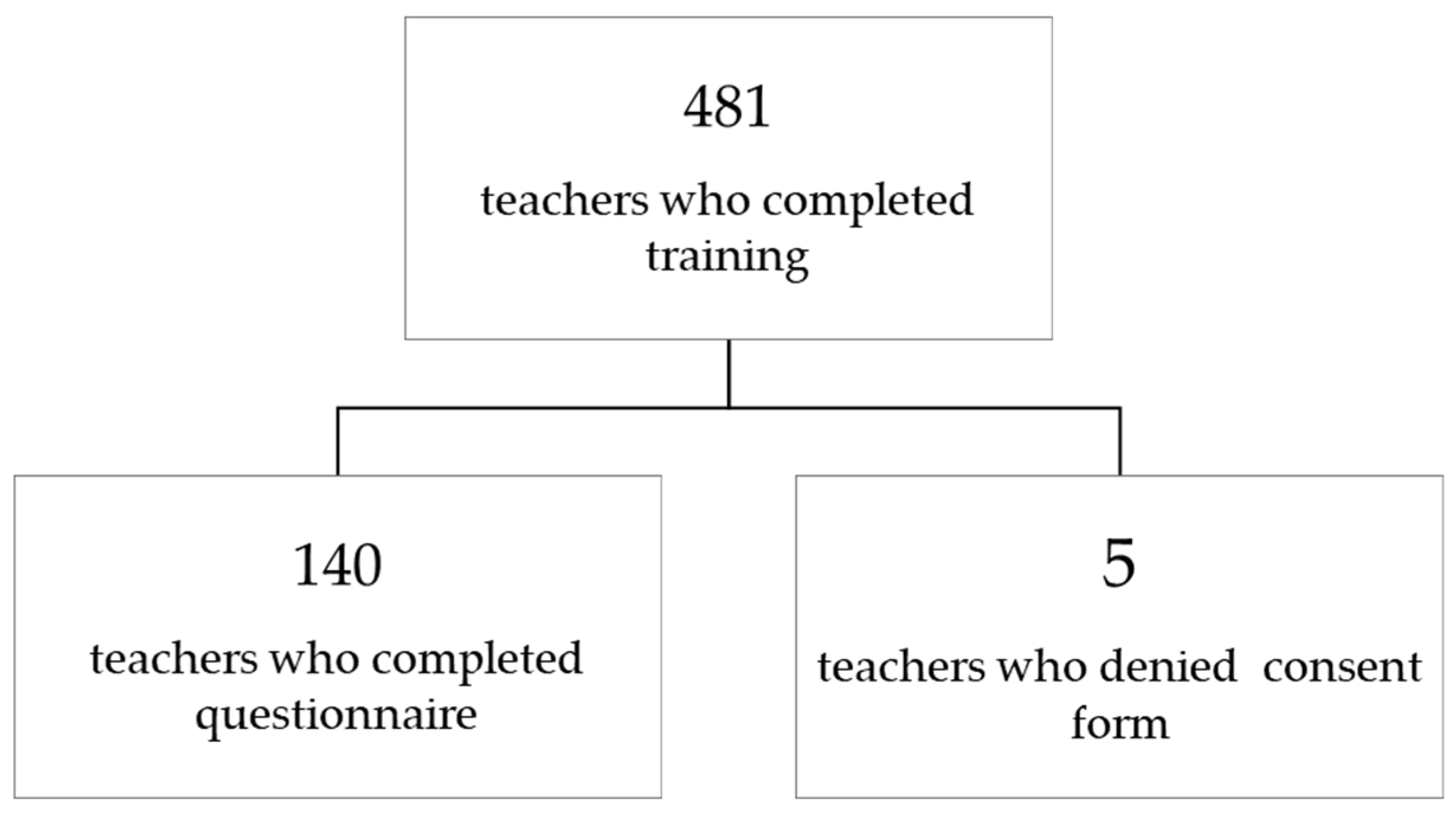

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Survey Questionnaire and Administration

- Teacher sociodemographic characteristics (4 items collecting data such as gender, teaching role, years of experience, and school level).

- Practicability, applicability, sustainability of ABs (9 items) and perceived benefits experienced during their use (7 items).

- Inclusion and disability (3 items, including those with special educational needs or diverse abilities).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

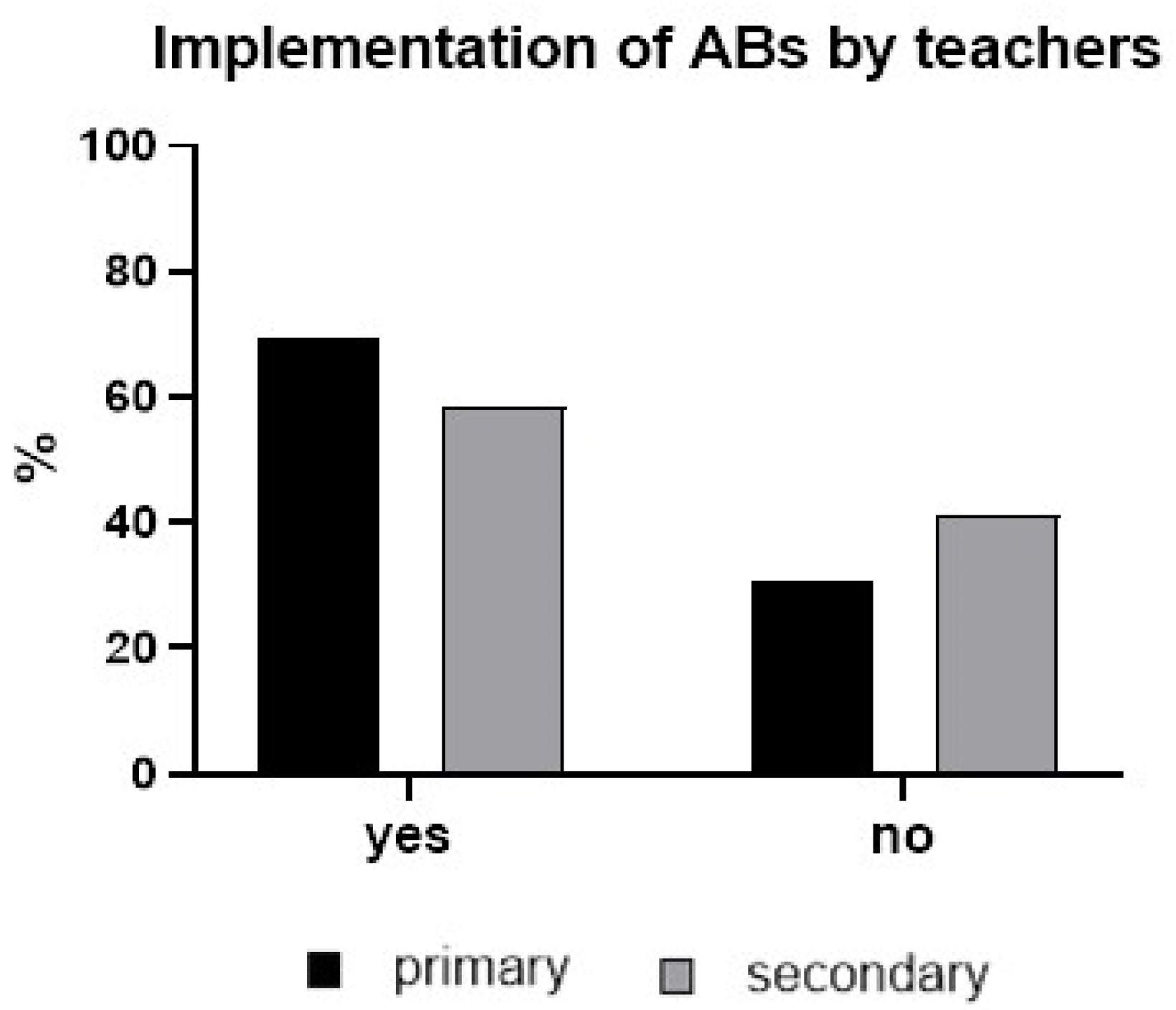

3.2. Teacher ABs Implementation

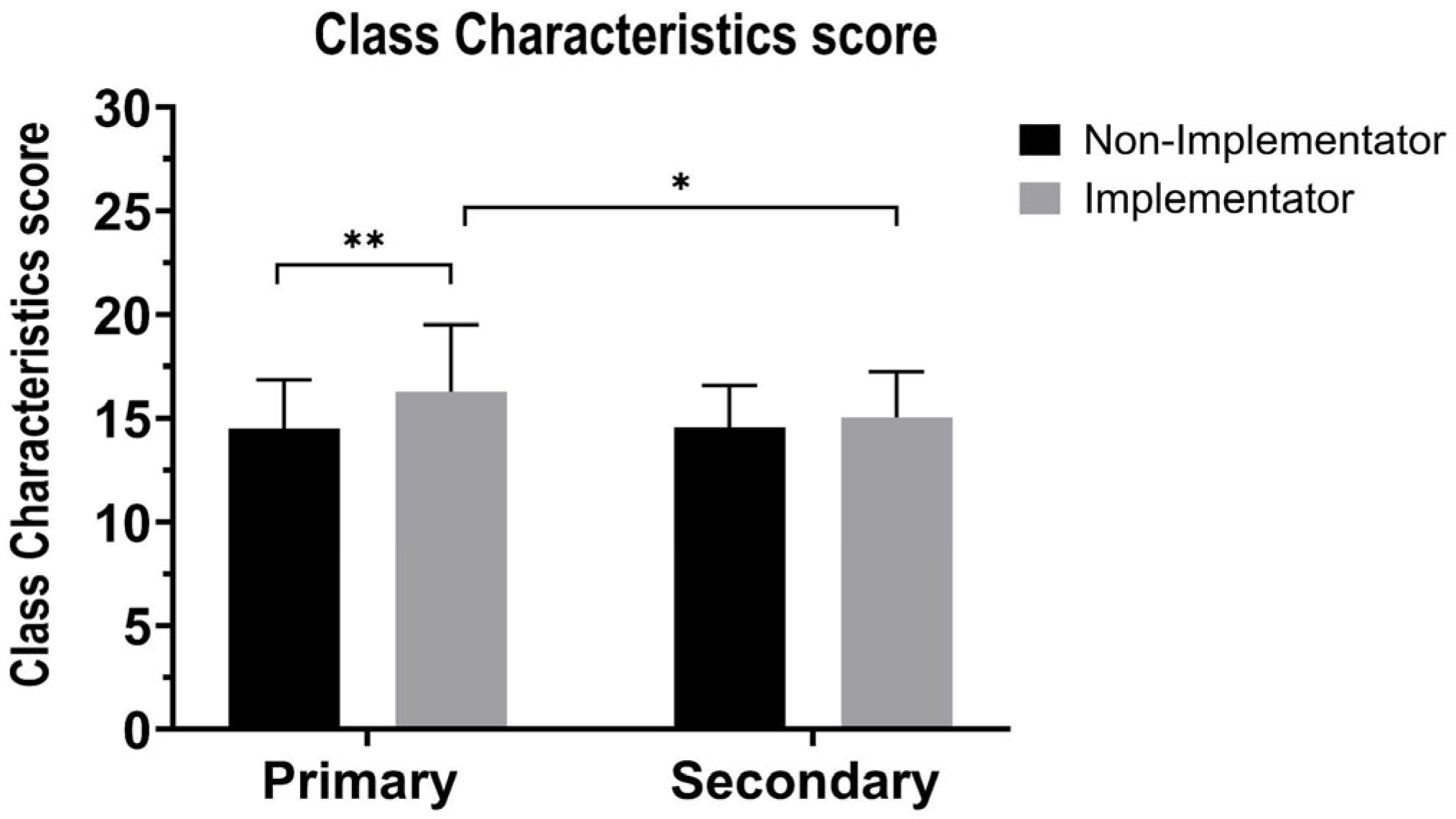

3.2.1. Teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes Toward ABs in the Classroom

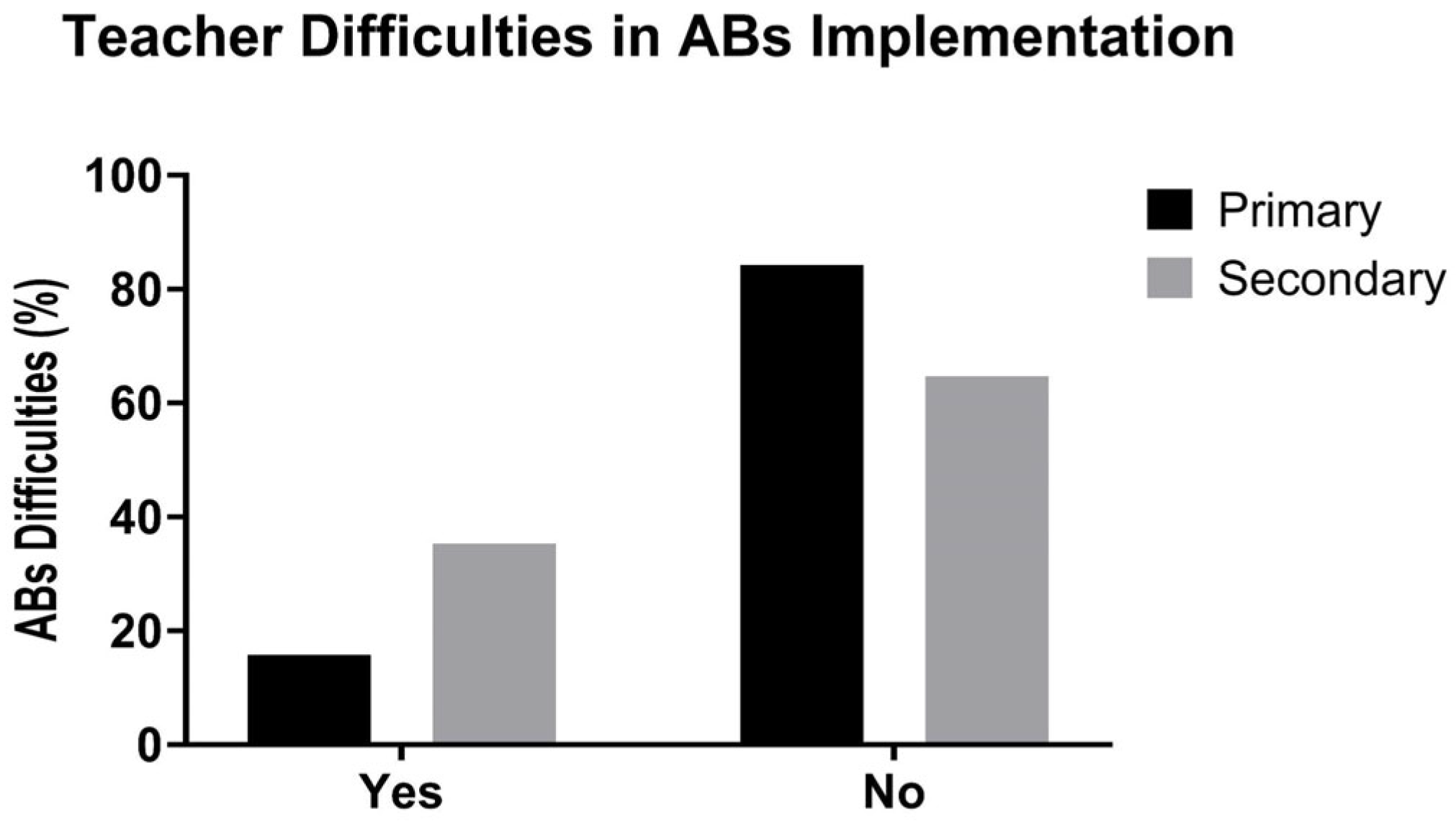

3.2.2. Perceived Difficulties and Barriers to ABs

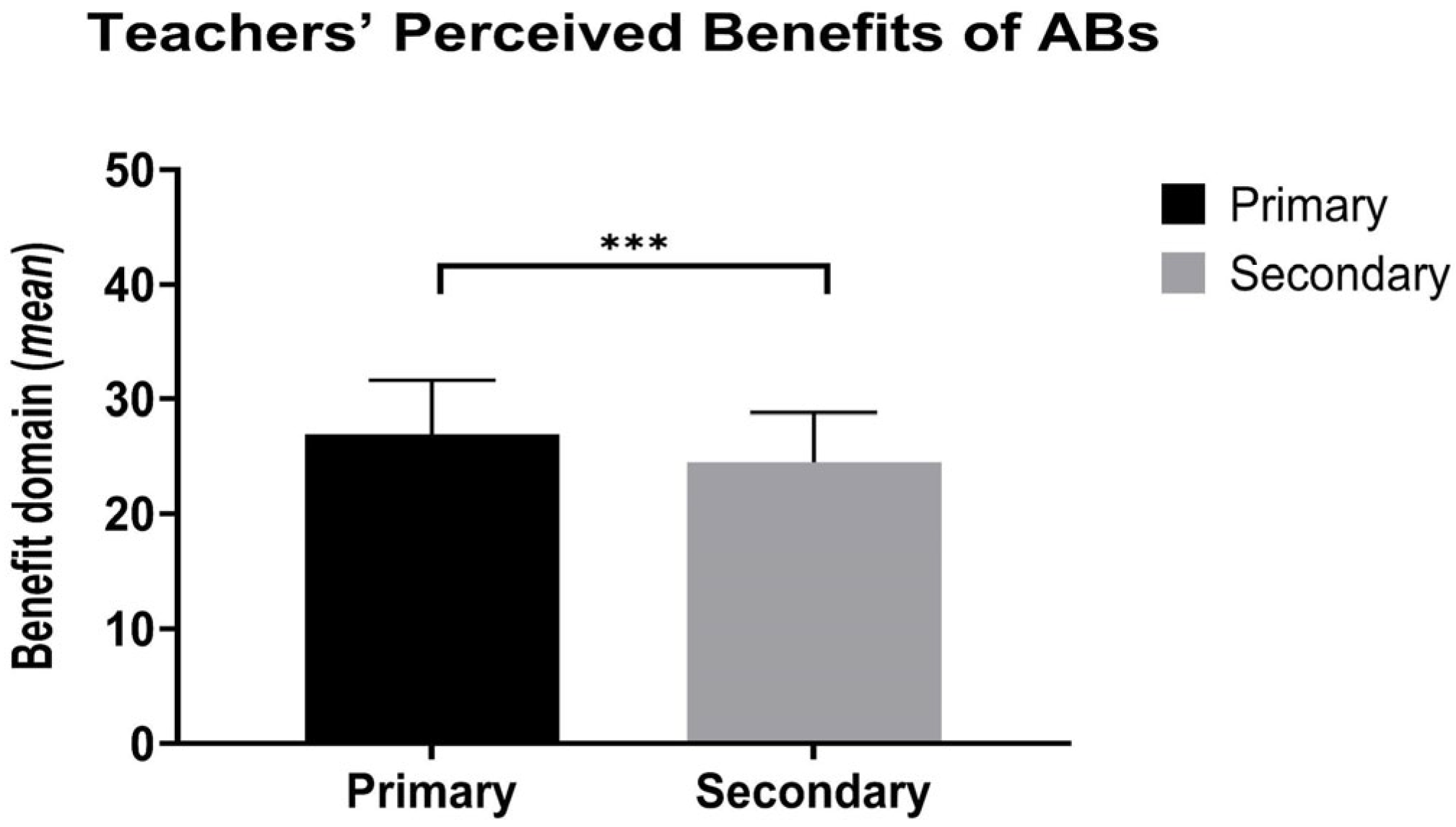

3.3. Practicability, Benefits, Applicability, and Sustainability of ABs in the Classroom

3.4. Inclusion and Disability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABs | Active Breaks |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| ATPA | Attitudes Towards Physical Activity |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| METs | Metabolic Equivalents |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| SBs | Sedentary Behavior |

| SURGE | Survey Reporting Guideline |

Appendix A

| Primary (N = 57) | Secondary (N = 34) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did you feel comfortable suggesting active breaks? | N. | % | N. | % |

| Definitely YES | 44 | 77.19 | 24 | 70.59 |

| More YES than NO | 12 | 21.05 | 8 | 23.53 |

| More NO than YES | 1 | 1.75 | 2 | 5.88 |

| In which month did you start performing active breaks? | ||||

| Autumn (September–November) | 19 | 33.33 | 4 | 11.76 |

| Winter (December–January–February) | 23 | 40.35 | 23 | 67.65 |

| Spring (March–April–May) | 15 | 26.32 | 7 | 20.59 |

| How often did you perform active breaks? | ||||

| A few times a week | 29 | 50.88 | 22 | 64.71 |

| A few times a month | 5 | 8.77 | 7 | 20.59 |

| Every day once a day | 12 | 21.05 | 5 | 14.71 |

| Every day several times a day | 11 | 19.30 | 0 | 0.00 |

| How long does an active break usually last? | ||||

| 15 min | 2 | 3.51 | 1 | 2.94 |

| 10 min | 34 | 59.65 | 14 | 41.18 |

| 5 min | 20 | 35.09 | 15 | 44.12 |

| Others | 1 | 1.75 | 4 | 11.76 |

| At what time of the school day is the active break most useful? | ||||

| Early morning | 16 | 28.07 | 4 | 11.76 |

| Midmorning | 25 | 43.86 | 26 | 76.47 |

| After lunch break | 6 | 10.53 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Afternoon | 8 | 14.04 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Other | 2 | 3.51 | 4 | 11.76 |

| What type of content did you use most frequently in active breaks? | ||||

| Cognitive | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.88 |

| Disciplinary | 3 | 5.26 | 1 | 2.94 |

| Motor | 39 | 68.42 | 23 | 67.65 |

| Relational | 1 | 1.75 | 2 | 5.88 |

| Mixed Content | 14 | 24.56 | 6 | 17.65 |

| Who led the active breaks? | ||||

| Teacher | 38 | 66.67 | 14 | 41.18 |

| Expert on educational project | 1 | 1.75 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Pupils | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 23.53 |

| Special needs teacher | 5 | 8.77 | 1 | 2.94 |

| Teacher and Pupils | 6 | 10.53 | 9 | 26.47 |

| Mixed Figures | 7 | 12.28 | 2 | 5.88 |

| During the active break did you use the interactive whiteboard? | ||||

| No | 49 | 85.96 | 28 | 82.35 |

| Yes | 8 | 14.04 | 6 | 17.65 |

| What digital teaching tools/applications have you used with the interactive whiteboard? * | ||||

| YouTube | 4 | 7.02 | 6 | 17.65 |

| Mixed tools | 4 | 7.02 | 2 | 5.88 |

| None | 49 | 85.96 | 28 | 82.36 |

| Primary (N = 57) | Secondary (N = 34) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were there pupils with disabilities in your class this year? | N. | % | N. | % |

| No | 20 | 35.09 | 10 | 29.41 |

| Yes | 34 | 59.65 | 22 | 64.71 |

| I prefer not to answer | 3 | 5.26 | 2 | 5.88 |

| Teachers who taught pupils with disabilities | (N = 34) | (N = 22) | ||

| Can you specify the type of disability referred to the pupils in your class? * | ||||

| Cognitive | 27 | 79.41 | 15 | 68.18 |

| Physical | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9.09 |

| Sensory | 2 | 5.88 | 0 | 0 |

| Cognitive and Physical | 1 | 2.94 | 1 | 4.55 |

| Cognitive and Sensory | 2 | 5.88 | 0 | 0 |

| I prefer not to answer | 2 | 5.88 | 4 | 18.18 |

| Was it necessary to adjust the timing/rhythms/scheduling of the ABs to meet the needs of the students with disabilities? * | ||||

| Never | 11 | 32.25 | 10 | 45.45 |

| Almost never | 8 | 23.53 | 2 | 9.09 |

| Rarely | 1 | 2.94 | 2 | 9.09 |

| Sometimes | 10 | 29.41 | 6 | 27.27 |

| Always | 4 | 11.76 | 2 | 9.09 |

References

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-001512-8. [Google Scholar]

- Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Borghese, M.M.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.-P.; Janssen, I.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Pate, R.R.; Connor Gorber, S.; Kho, M.E.; et al. Systematic Review of the Relationships between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S197–S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, E.; Salmon, J.; Pesce, C.; Teo, W.-P.; Rinehart, N.; May, T.; Barnett, L.M. Effects of Classroom-based Active Breaks on Cognition, Sitting and On-task Behaviour in Children with Intellectual Disability: A Pilot Study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 464–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sit, C.; Li, R.; McKenzie, T.L.; Cerin, E.; Wong, S.; Sum, R.; Leung, E. Physical Activity of Children with Physical Disabilities: Associations with Environmental and Behavioral Variables at Home and School. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Willumsen, J.; Bull, F.; Chou, R.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Jago, R.; Ortega, F.B.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. 2020 WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour for Children and Adolescents Aged 5–17 Years: Summary of the Evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steene-Johannessen, J.; Hansen, B.H.; Dalene, K.E.; Kolle, E.; Northstone, K.; Møller, N.C.; Grøntved, A.; Wedderkopp, N.; Kriemler, S.; Page, A.S.; et al. Variations in Accelerometry Measured Physical Activity and Sedentary Time across Europe—Harmonized Analyses of 47,497 Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, H.; Fiedler, J.; Wunsch, K.; Woll, A.; Wollesen, B. mHealth Interventions to Reduce Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e35920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Gray, C.E.; Poitras, V.J.; Chaput, J.-P.; Saunders, T.J.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Okely, A.D.; Connor Gorber, S.; et al. Systematic Review of Sedentary Behaviour and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth: An Update. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, S240–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thivel, D.; Tremblay, A.; Genin, P.M.; Panahi, S.; Rivière, D.; Duclos, M. Physical Activity, Inactivity, and Sedentary Behaviors: Definitions and Implications in Occupational Health. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.; Laddu, D.R.; Phillips, S.A.; Lavie, C.J.; Arena, R. A Tale of Two Pandemics: How Will COVID-19 and Global Trends in Physical Inactivity and Sedentary Behavior Affect One Another? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 64, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Saunders, T.J.; Carson, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Altenburg, T.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN)—Terminology Consensus Project Process and Outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Abdeta, C.; Abi Nader, P.; Adeniyi, A.F.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Andrade Tenesaca, D.S.; Bhawra, J.; Brazo-Sayavera, J.; Cardon, G.; et al. Global Matrix 3.0 Physical Activity Report Card Grades for Children and Youth: Results and Analysis From 49 Countries. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, S251–S273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsson, I.Þ.; Jóhannsson, E.; Daly, D.; Arngrímsson, S.Á. Physical Activity during School and after School among Youth with and without Intellectual Disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 56, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, C.H.P.; McManus, A.; McKenzie, T.L.; Lian, J. Physical Activity Levels of Children in Special Schools. Prev. Med. 2007, 45, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maïano, C. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Overweight and Obesity among Children and Adolescents with Intellectual Disabilities. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, M.; Evenhuis, H.M.; Hilgenkamp, T.I.M. Physical Fitness of Children and Adolescents with Moderate to Severe Intellectual Disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2542–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levit-Binnun, N.; Davidovitch, M.; Golland, Y. Sensory and Motor Secondary Symptoms as Indicators of Brain Vulnerability. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2013, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A.; Downing, K.; Rinehart, N.J.; Barnett, L.M.; May, T.; McGillivray, J.A.; Papadopoulos, N.V.; Skouteris, H.; Timperio, A.; Hinkley, T. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and Their Correlates in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, P.S.; Sasser, T.; Gonzalez, E.S.; Whitlock, K.B.; Christakis, D.A.; Stein, M.A. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep in Children With ADHD. J. Phys. Act. Health 2019, 16, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, K.; Milne, N.; Pope, R.; Orr, R. Factors Influencing the Provision of Classroom-Based Physical Activity to Students in the Early Years of Primary School: A Survey of Educators. Early Child. Educ. J. 2021, 49, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.; Kulinna, P.; Cothran, D. Chapter 5 Physical Activity Opportunities During the School Day: Classroom Teachers’ Perceptions of Using Activity Breaks in the Classroom. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2014, 33, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Amigo, T.; Ibarra-Mora, J.; Aguilar-Farías, N.; Gómez-Álvarez, N.; Carrasco-Beltrán, H.; Zapata-Lamana, R.; Hurtado-Almonácid, J.; Páez-Herrera, J.; Yañez-Sepulveda, R.; Cortés, G.; et al. An Active Break Program (ACTIVA-MENTE) at Elementary Schools in Chile: Study Protocol for a Pilot Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1243592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallolio, L.; Gallè, F.; Masini, A. Active Breaks: A Strategy to Counteract Sedentary Behaviors for Health Promoting Schools. A Discussion on Their Implementation in Italy. Ann. Ig. Med. Prev. E Comunità 2023, 35, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.A.; Engelberg, J.K.; Cain, K.L.; Conway, T.L.; Mignano, A.M.; Bonilla, E.A.; Geremia, C.; Sallis, J.F. Implementing Classroom Physical Activity Breaks: Associations with Student Physical Activity and Classroom Behavior. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Drew, R.; Morgan, P.J.; Lubans, D.R.; Schmidt, M.; Riley, N. Effects of Different Types of Classroom Physical Activity Breaks on Children’s On-task Behaviour, Academic Achievement and Cognition. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Marini, S.; Ceciliani, A.; Barone, G.; Lanari, M.; Gori, D.; Bragonzoni, L.; Toselli, S.; Stagni, R.; Bisi, M.C.; et al. The Effects of an Active Breaks Intervention on Physical and Cognitive Performance: Results from the I-MOVE Study. J. Public Health 2023, 45, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Amigo, T.; Salinas-Gallardo, G.; Mendoza, E.; Ovalle-Fernández, C.; Ibarra-Mora, J.; Gómez-Álvarez, N.; Carrasco-Beltrán, H.; Páez-Herrera, J.; Hurtado-Almonácid, J.; Yañez-Sepúlveda, R.; et al. Effectiveness of School-Based Active Breaks on Classroom Behavior, Executive Functions and Physical Fitness in Children and Adolescent: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1469998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantes-Paniagua, Á.; Silva, A.F.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Sarmento, H.; González-Fernández, F.T.; González-Víllora, S.; Clemente, F.M. Active School Breaks and Students’ Attention: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, N.M.; Michaliszyn, S.F.; Kelly-Miller, N.; Groll, L. Elementary School Classroom Physical Activity Breaks: Student, Teacher, and Facilitator Perspectives. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2019, 43, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Ceciliani, A.; Dallolio, L.; Gori, D.; Marini, S. Evaluation of Feasibility, Effectiveness, and Sustainability of School-Based Physical Activity “Active Break” Interventions in Pre-Adolescent and Adolescent Students: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Public Health 2022, 113, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, N.; Mantilla, A.; Bussey, K.; Emonson, C.; Olive, L.; McGillivray, J.; Pesce, C.; Lewis, S.; Rinehart, N. Understanding the Benefits of Brief Classroom-Based Physical Activity Interventions on Primary School-Aged Children’s Enjoyment and Subjective Wellbeing: A Systematic Review. J. Sch. Health 2022, 92, 916–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, V.; Salimi, R.; De Groot, R.; Jolles, J.; Chinapaw, M.; Singh, A. “It’s a Battle… You Want to Do It, but How Will You Get It Done?”: Teachers’ and Principals’ Perceptions of Implementing Additional Physical Activity in School for Academic Performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelona, J.; Centeio, E.; Phillips, S.; Gleeson, D.; Mercier, K.; Foley, J.; Simonton, K.; Garn, A. Comprehensive School Health: Teachers’ Perceptions and Implementation of Classroom Physical Activity Breaks in US Schools. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daac100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.L.; Lassiter, J.W. Teacher Perceptions of Facilitators and Barriers to Implementing Classroom Physical Activity Breaks. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 113, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKown, H.B.; Centeio, E.E.; Barcelona, J.M.; Pedder, C.; Moore, E.W.G.; Erwin, H.E. Exploring Classroom Teachers’ Efficacy towards Implementing Physical Activity Breaks in the Classroom. Health Educ. J. 2022, 81, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, K.; Gebhardt, M.; Mäehler, C. Working Memory Functions in Children with Different Degrees of Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2010, 54, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero della Salute Piano Nazionale Della Prevenzione 2020–2025. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_notizie_5029_0_file.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Bennett, C.; Khangura, S.; Brehaut, J.C.; Graham, I.D.; Moher, D.; Potter, B.K.; Grimshaw, J.M. Reporting Guidelines for Survey Research: An Analysis of Published Guidance and Reporting Practices. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.; Hwang, H.-J. The Importance of Anonymity and Confidentiality for Conducting Survey Research. J. Res. Publ. Ethics 2023, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, L.; Bigelow, H.; Graham, J.D.; Ogrodnik, M.; Chiodo, D.; Fenesi, B. A Mixed Method Investigation of Teacher-Identified Barriers, Facilitators and Recommendations to Implementing Daily Physical Activity in Ontario Elementary Schools. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, M.M.C.; Chin, M.K.; Chen, S.; Emeljanovas, A.; Mieziene, B.; Bronikowski, M.; Laudanska-Krzeminska, I.; Milanovic, I.; Pasic, M.; Balasekaran, G.; et al. Psychometric Properties of the Attitudes toward Physical Activity Scale: A Rasch Analysis Based on Data From Five Locations. J. Appl. Meas. 2015, 16, 379–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, A.P.; Parker, E.A.; Lane, H.G.; Deitch, R.; Wang, Y.; Turner, L.; Hager, E.R. Physical Activity, Confidence, and Social Norms Associated With Teachers’ Classroom Physical Activity Break Implementation. Health Promot. Pract. 2024, 25, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draugalis, J.R.; Plaza, C.M. Best Practices for Survey Research Reports Revisited: Implications of Target Population, Probability Sampling, and Response Rate. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009, 73, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). (EU 2016/679). Available online: https://gdpr-info.eu (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Wilson, A.B.; Brooks, W.S.; Edwards, D.N.; Deaver, J.; Surd, J.A.; Pirlo, O.J.; Byrd, W.A.; Meyer, E.R.; Beresheim, A.; Cuskey, S.L.; et al. Survey Response Rates in Health Sciences Education Research: A 10-year Meta-analysis. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2024, 17, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Education and Culture Executive Agency. Eurydice. In The European Higher Education Area in 2024: Bologna Process Implementation Report; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dinkel, D.; Schaffer, C.; Snyder, K.; Lee, J.M. They Just Need to Move: Teachers’ Perception of Classroom Physical Activity Breaks. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Russ, L.; Vazou, S.; Goh, T.L.; Erwin, H. Integrating Movement in Academic Classrooms: Understanding, Applying and Advancing the Knowledge Base. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Longo, G.; Ricci, M.; Scheier, L.M.; Sansavini, A.; Ceciliani, A.; Dallolio, L. Investigating Facilitators and Barriers for Active Breaks among Secondary School Students: Formative Evaluation of Teachers and Students. Children 2024, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masini, A.; Marini, S.; Gori, D.; Leoni, E.; Rochira, A.; Dallolio, L. Evaluation of School-Based Interventions of Active Breaks in Primary Schools: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2020, 23, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Murtagh, E.M. Teachers’ and Students’ Perspectives of Participating in the ‘Active Classrooms’ Movement Integration Programme. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, R.D.; Webster, C.A.; Egan, C.A.; Nilges, L.; Brian, A.; Johnson, R.; Carson, R.L. Facilitators and Barriers to Movement Integration in Elementary Classrooms: A Systematic Review. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2019, 90, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, C.H.P.; Mckenzie, T.L.; Cerin, E.; Chow, B.C.; Huang, W.Y.; Yu, J. Physical Activity and Sedentary Time among Children with Disabilities at School. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzoli, E.; Koorts, H.; Salmon, J.; Pesce, C.; May, T.; Teo, W.-P.; Barnett, L.M. Feasibility of Breaking up Sitting Time in Mainstream and Special Schools with a Cognitively Challenging Motor Task. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, D.D.; Courtney-Long, E.A.; Stevens, A.C.; Sloan, M.L.; Lullo, C.; Visser, S.N.; Fox, M.H.; Armour, B.S.; Campbell, V.A.; Brown, D.R.; et al. Vital Signs: Disability and Physical Activity--United States, 2009–2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| (N = 140) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 123 | 87.9 |

| Male | 17 | 12.1 |

| Level of education | ||

| No graduate degree | 24 | 17.1 |

| Bachelor’s and master’s degrees | 116 | 82.9 |

| Years of experience as a teacher | ||

| 1–10 | 46 | 32.9 |

| 11–20 | 44 | 31.4 |

| +21 | 50 | 35.7 |

| School type | ||

| Primary School | 82 | 58.6 |

| Middle and High school | 58 | 41.4 |

| Non-Implementers (N = 49) M ± SD | Implementers (N = 91) M ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| INDIVIDUAL PERCEPTIONS * | 14.16 ± 2.63 | 16.63 ± 3.01 |

| Feels able to conduct ABs with students | ||

| Feels motivated to propose ABs | ||

| Feels able to encourage students to practice ABs | ||

| Feels/would feel safe to implement Abs | ||

| CLASS CHARACTERISTICS * | 10.31 ± 1.75 | 11.71 ± 2.25 |

| Think students behave/could behave well during Abs | ||

| During the school day, there is time to do Abs | ||

| It is possible/would be likely to implement ABs with its students | ||

| SUPPORTING THE SCHOOL EDUCATION NETWORK * | 14.55 ± 2.17 | 15.83 ± 2.93 |

| The school is committed to promoting the health and well-being of students | ||

| Parents of pupils support the implementation of ABs | ||

| Colleagues support the implementation of ABs | ||

| The school principal supports the implementation of the ABs |

| Non-Implementers (N = 49) | Implementers (N = 21) | |

|---|---|---|

| BARR1 Space available is adequate | 2.75 ± 1.02 | 2.38 ± 0.90 |

| BARR2 No fear of injuries | 3.32 ± 0.98 | 3.61 ± 0.90 |

| BARR3 Material is sufficient | 3.12 ± 0.77 | 3.38 ± 1.05 |

| BARR4 Bureaucratic process for ABs is simple | 3.10 ± 0.71 | 3.33 ± 0.99 |

| BARR5 Class is too large | 2.83 ± 0.96 | 3.09 ± 1.02 |

| BARR6 Class is easy to manage | 2.81 ± 0.96 | 2.61 ± 1.13 |

| BARR7 Training is sufficient | 3.16 ± 0.74 | 3.23 ± 1.02 |

| BARR8 Time available is sufficient | 3.14 ± 0.83 | 3.19 ± 0.85 |

| PRIMARY M ± SD | SECONDARY M ± SD | |

|---|---|---|

| ABs help children sit more easily | 4.02 ± 0.64 | 3.39 ± 0.82 |

| ABs facilitate the achievement of learning objectives | 3.29 ± 0.69 | 3.35 ± 0.68 |

| ABs facilitate conflict management | 3.54 ± 0.78 | 3.09 ± 0.70 |

| ABs are simple and fun | 4.32 ± 0.68 | 4.03 ± 0.85 |

| ABs are more effective than other strategies | 3.82 ± 0.60 | 3.56 ± 0.85 |

| ABs improve the classroom environment | 4.00 ± 0.71 | 3.71 ± 0.89 |

| ABs facilitate behavior management | 3.89 ± 0.84 | 3.47 ± 0.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Persiani, M.; Ceciliani, A.; Russo, G.; Dallolio, L.; Senesi, G.; Bragonzoni, L.; Montalti, M.; Sacchetti, R.; Masini, A. Active Breaks in Primary and Secondary School Children and Adolescents: The Point of View of Teachers. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192482

Persiani M, Ceciliani A, Russo G, Dallolio L, Senesi G, Bragonzoni L, Montalti M, Sacchetti R, Masini A. Active Breaks in Primary and Secondary School Children and Adolescents: The Point of View of Teachers. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192482

Chicago/Turabian StylePersiani, Michela, Andrea Ceciliani, Gabriele Russo, Laura Dallolio, Giulio Senesi, Laura Bragonzoni, Marco Montalti, Rossella Sacchetti, and Alice Masini. 2025. "Active Breaks in Primary and Secondary School Children and Adolescents: The Point of View of Teachers" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192482

APA StylePersiani, M., Ceciliani, A., Russo, G., Dallolio, L., Senesi, G., Bragonzoni, L., Montalti, M., Sacchetti, R., & Masini, A. (2025). Active Breaks in Primary and Secondary School Children and Adolescents: The Point of View of Teachers. Healthcare, 13(19), 2482. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192482