Exploring a Systems-Based Model of Care for Effective Healthcare Transformation: A Narrative Review in Implementation Science of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

Search Strategy and Transparency

2. Conceptual Framework of the Saudi Model of Care

2.1. Defining Systems-Based Care

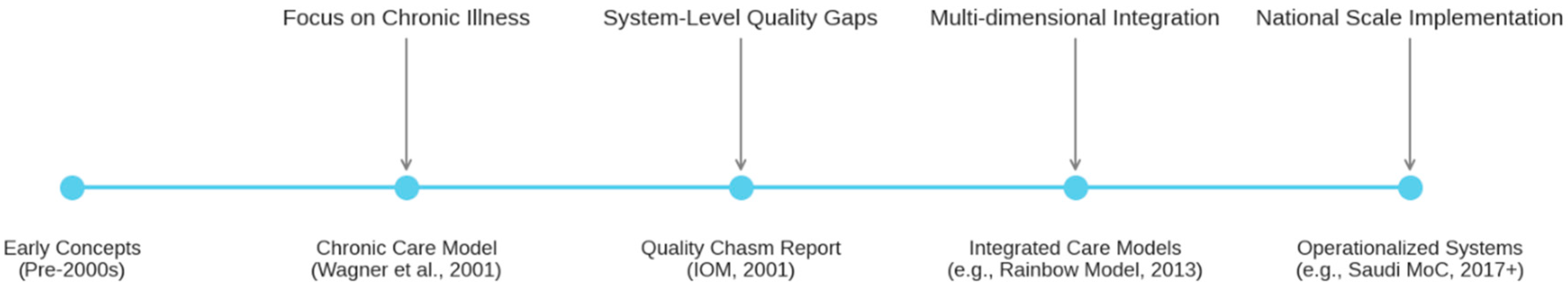

2.2. Evolution of Systems Thinking in Healthcare

2.3. Key Characteristics of the Saudi MoC

2.3.1. Integrated Healthcare Model of Care Framework

2.3.2. Patient-Centered “Six Asks” Framework

- Keep Well: How will the system support me to stay healthy and prevent illness?

- Urgent Problem: How will the system support me effectively and efficiently when I have an urgent health problem?

- Planned Procedure: How will the system support me to achieve a great and consistent outcome for my planned procedure?

- Safe Birth: How will the system support me (and my family) to safely deliver a healthy baby?

- Chronic Condition: How will the system support me in managing my chronic conditions effectively over the long term?

- Last Phase: How will the system provide compassionate and supportive care during the last phase of my life?

2.3.3. Guiding Principles

- Patient Activation and Empowerment: Placing individuals and families at the center, equipping them with knowledge and tools to actively participate in their health and care. Tools include apps for self-monitoring and educational portals. Desired outcomes include reduced chronic disease complications and improved quality of life. Incentives are value-based, rewarding outcomes rather than production.

- Prevention over Cure: Shifting focuses on proactive health promotion and disease prevention, rather than solely reacting to illness.

- Outcome over Activity: Emphasizing the achievement of desired health outcomes and value for patients, rather than merely measuring the volume of services delivered.

- Integration “from Hospital to Home”: Ensuring seamless coordination and continuity of care across all settings, encompassing physical, mental, and social wellbeing.

- Value-Based Care: Aligning resources and incentives to deliver high-quality care efficiently and effectively.

2.3.4. Core Themes

- From hospital-centric to home- and community-based care.

- From focusing on volume of activity to focusing on health outcomes and value.

- From a predominantly treatment-focused approach to one emphasizing prevention and wellbeing.

- From siloed institutions to integrated service networks.

- From reliance on physical buildings to leveraging virtual services.

- From viewing patients as passive recipients to engaging them as active participants in their care.

3. Results

3.1. Intervention Characteristics

3.2. Outer Setting

3.3. Inner Setting

3.4. Characteristics of Individuals

3.5. Implementation Process

- Intervention Characteristics: The MoC provides detailed specifications for its 42 interventions, articulates their relative advantages (projected health benefits), allows for adaptability to different contexts, and presents them within comprehensive documentation.

- Outer Setting: The model aligns with patient needs (through the “Six Asks”), responds to external pressures (global trends, Vision 2030 mandate), and considers the broader policy environment.

- Inner Setting: It plans for structural changes (e.g., National Referral Networks), aims to influence organizational culture (patient activation), considers the implementation climate (resource allocation, planned incentives), and emphasizes leadership engagement.

- Individuals Involved: The strategy includes components for building knowledge and skills (training), enhancing self-efficacy (capability building), and managing the change process for individuals.

- Implementation Process: The MoC outlines specific stages for planning, engaging stakeholders (co-creation approach mentioned in initial design), executing (phased rollout), and reflecting/evaluating (monitoring framework).

3.6. Phased Implementation Approach

- Developing Governance Structure: Establishing dedicated teams at national, regional (cluster), and organizational levels to oversee and coordinate implementation.

- Building Capability: Investing in training and development for implementation teams and frontline staff to equip them with the necessary knowledge and skills.

- Prioritizing Interventions: Strategically sequencing interventions, potentially identifying “quick wins” achievable with existing resources alongside medium- and long-term actions requiring more significant enablers.

- Developing System Plans: Creating detailed operational plans for implementing each intervention within the specific context of healthcare clusters or organizations.

- Phased Rollout in Clusters: Implementing the model progressively across the approximately 20 regional healthcare clusters being formed in the Kingdom, allowing for learning and adaptation between phases.

3.7. Contextual Adaptations

- Geographic Contexts: Tailoring service delivery profiles and intervention implementation based on whether a setting is classified as a city (access to tertiary hospital), town (access to general hospital), or rural area (access primarily to primary care centers). This considers differences in available facilities, workforce density, population distribution, and geography.

- Special Populations and Contexts: Developing specific considerations and pathway adjustments for unique situations, including the massive Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages (requiring surge capacity and specific public health measures), pediatric services (addressing the distinct needs of children), and mental health services (acknowledging the need for integration and development in this area).

3.8. Enabling Infrastructure

- Workforce: Redesigning roles, enhancing training, ensuring appropriate staffing levels, and potentially allowing for more flexible scopes of practice to meet the demands of the new model.

- eHealth Infrastructure: Implementing robust digital health solutions, including the Integrated Personal Health Record, e-referral platforms, telehealth capabilities, and data analytics systems.

- Payment Reform: Shifting reimbursement mechanisms away from fee-for-service towards value-based payment models that incentivize desired outcomes, prevention, and efficiency.

- Private Sector Participation: Defining and facilitating the role of the private sector in contributing to the goals of the MoC, potentially through partnerships or specific service provision.

- Cluster Governance and National Regulation: Establishing effective governance structures within the regional health clusters and ensuring appropriate national regulatory frameworks are in place to support the transformed system.

3.9. Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

- Systematic Data Collection: Aiming to establish a unified system for collecting comprehensive data on population health, service utilization, quality, and expenditure from both public and private providers.

- Outcomes Monitoring: Developing a national system for continuously tracking key population health indicators and patient-reported outcomes, building on existing clinical audit capabilities.

4. Health Outcomes and Value Proposition

4.1. Health Outcomes Framework

4.2. Comprehensive Value Proposition

- Improved Health Outcomes: The MoC aims to improve the health of the population. Through targeted interventions, particularly those addressing leading causes of mortality like road traffic accidents and cardiovascular disease, the model projects significant health improvements, including increased average life expectancy in the Kingdom to 80 years by 2030, surpassing previous UN projections [16].

- Enhanced Patient Experience: Through its patient-centered design and specific interventions like the Health Coach Program, Virtual Self-Care Tools, and Enhanced Primary Care Services, the MoC aims to improve patient satisfaction, promote activation and engagement in self-care, and create a more navigable and supportive healthcare journey.

- System Efficiency and Integration: By addressing fragmentation and improving coordination, interventions such as National Referral Networks, Integrated Personal Health Records, and Case Coordination are intended to create a more seamless patient experience across different care settings, reduce duplication of services, and improve overall system efficiency.

- Workforce Development and Satisfaction: The model’s emphasis on team-based care, enhanced training, and potentially optimizing scopes of practice aims not only to build the necessary capacity but also to improve provider engagement and satisfaction, recognizing the critical role of the healthcare workforce in successful transformation.

4.3. Health Impact Framework

- Prevention and Early Intervention: Decreasing the burden of disease through enhanced prevention, health promotion, and early detection. This includes reducing risk factors for chronic diseases, preventing accidents, and promoting healthy lifestyles.

- Care Quality and Integration: Improving health outcomes through better care coordination, evidence-based practices, and patient engagement. This encompasses streamlining pathways, reducing complications, and improving care continuity across settings.

4.4. Implementation Considerations

- Time Horizon: Many health improvements, particularly from preventive interventions, may take years or decades to fully materialize. Long-term monitoring will be essential to capture these benefits.

- Attribution Challenges: In any complex, system-wide transformation involving multiple concurrent initiatives, definitively attributing observed changes in health outcomes to specific MoC interventions poses significant methodological challenges.

- Population Diversity: The impact may vary across different geographic regions, population subgroups, and socioeconomic contexts, requiring careful monitoring of equity in outcomes.

- Implementation Fidelity: Actual health outcomes will depend heavily on the quality and consistency of implementation across different settings and the successful development of enabling infrastructure.

5. Discussion

5.1. Synthesis of Findings

5.2. Distinctive Features and Contributions of the Saudi MoC

- Operationalizing Systems Thinking at National Scale: While many systems frameworks exist, the MoC provides a rare example of a nation attempting to translate these principles into a concrete, operational plan for its entire public healthcare system.

- Novel Organizing Principle (Six Asks): Structuring a national model around patient life-course needs rather than traditional administrative or specialty boundaries is an innovative approach that warrants further study regarding its impact on integration and patient experience.

- Explicit Integration of Non-Clinical Layers: The formal inclusion of activated individuals, healthy communities, and virtual care as core architectural layers represents a significant attempt to bridge the gap between clinical healthcare, public health, and self-management.

- Detailed Intervention Specification: The granular level of detail in defining the 42 interventions provides a practical blueprint that contrasts with more high-level strategic plans often seen in other contexts.

- Planned Contextual Adaptation: The foresight in planning for variations across geographic settings and special populations demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of implementation challenges in diverse environments.

- Alignment with Implementation Science: The conscious incorporation of elements like phased rollout, stakeholder engagement (in design), capability building, and performance monitoring reflects an appreciation for the science of translating policy into practice.

5.3. Critical Analysis: Strengths and Potential Challenges

- Implementation Complexity: Coordinating 42 interventions across multiple layers, six systems of care, and ~20 regional clusters, while simultaneously developing five major enablers, represents an enormous implementation challenge requiring exceptional leadership, coordination, and sustained commitment.

- Dependence on Enablers: The success of many interventions is heavily contingent on progress in developing the enabling infrastructure, particularly eHealth systems (like the integrated PHR) and workforce redesign. Delays or shortcomings in these areas could significantly impede progress.

- Cultural and Behavioral Change: Shifting towards patient activation, prevention, and team-based care requires substantial changes in the attitudes and behaviors of both the public and healthcare professionals, which can be difficult and slow to achieve.

- Potential for Implementation Gaps: As with any large-scale plan, there is a risk of gaps between the intended design and actual implementation on the ground (implementation fidelity). Ensuring consistent adoption across diverse settings will be critical.

- Sustaining Momentum: The model requires long-term commitment and sustained investment in change management. Maintaining momentum across political and administrative transitions will be crucial.

- A notable implementation risk concerns the lag in payment reform and private-sector participation. Several MoC interventions presuppose the existence of value-based purchasing mechanisms and active private-sector engagement. However, while these are defined as enabling components in the MoC framework (2017 Overview, 2025 V2.0), they remain in early stages of development. At present, service delivery reforms are being rolled out, but financing reform and regulatory frameworks to incentivize value remain partly aspirational. This distinction between implemented elements and planned enablers must be recognized in assessing both progress and risks. To illustrate these linkages, Supplementary Table S2 presents a logic pathway connecting the Six Asks with exemplary interventions, required enablers, and intended outcomes.

5.4. Comparison with International Initiatives

5.5. Implementation Challenges and Success Factors

- Sustained Leadership and Vision: Consistent political and administrative leadership committed to the long-term vision is paramount.

- Effective Stakeholder Engagement: Ongoing engagement with patients, frontline clinicians, managers, and private sector partners is crucial for buy-in, co-design of solutions, and addressing emergent barriers.

- Adaptive Management and Learning: The ability of the system, particularly the cluster governance structures, to monitor progress, learn from experience, and adapt strategies flexibly will be vital.

- Alignment of Incentives: Ensuring that payment systems and non-financial incentives consistently support the desired changes in practice is essential.

- Balancing Fidelity and Adaptation: Effectively managing the tension between implementing the core components of the model faithfully while allowing necessary adaptations for local contexts requires careful oversight and evaluation.

- Capacity Building: Continuous investment in training and support for the workforce to develop the new skills and competencies required by the MoC.

5.6. Generalizability and Lessons Learned

- The value of a comprehensive, multi-layered conceptual framework that explicitly integrates clinical care with prevention, self-management, and community resources.

- The potential utility of structuring care around patient life-course needs as an alternative to traditional silos.

- The importance of detailed intervention planning alongside high-level strategy.

- The critical need to proactively plan for contextual adaptation within national programs.

- The necessity of co-developing key enablers (workforce, eHealth, payment) in parallel with service delivery changes.

- The essential role of a robust monitoring and evaluation framework informed by implementation science.

- Unique features include Vision 2030 financing and Hajj adaptations; generalizable elements encompass the Six Asks framework and phased rollout.

5.7. Policy Implications

5.8. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, K.; Soucat, A.; Kutzin, J.; Brindley, C.; Maele, V.; Touré, H.; Aranguren, M.; Li, D.; Barroy, H.; Flores, G.; et al. Public Spending on Health: A Closer Look at Global Trends; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Framework on Integrated People-Centred Health Services; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/integrated-people-centered-care (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- OECD. Rethinking Health System Performance Assessment: A Renewed Framework; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/rethinking-health-system-performance-assessment-844c0ba3-en.htm (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- OECD. Improved Health System Performance Through Better Care Coordination; OECD Health Working Papers No. 149; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Future of Health Systems: Resilience, Equity, Sustainability; OECD Policy Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/the-future-of-health-systems.html (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Plsek, P.E.; Greenhalgh, T. The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001, 323, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturmberg, J.P.; Martin, C.M.; Katerndahl, D.A. Systems and complexity thinking in the general practice literature: An integrative, historical narrative review. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlie, E.B.; Shortell, S.M. Improving the quality of health care in the United Kingdom and the United States: A framework for change. Milbank Q. 2001, 79, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.H.; Austin, B.T.; Davis, C.; Hindmarsh, M.; Schaefer, J.; Bonomi, A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001, 20, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- America, I.; Staff, I. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valentijn, P.P.; Schepman, S.M.; Opheij, W.; Bruijnzeels, M.A. Understanding integrated care: A comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2013, 13, e010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratwani, R.; Fairbanks, T.; Savage, E.; Adams, K.; Wittie, M.; Boone, E.; Hayden, A.; Barnes, J.; Hettinger, Z.; Gettinger, A. Mind the gap. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2016, 7, 1069–1087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hinrichs, S.; Jahagirdar, D.; Miani, C.; Guerin, B.; Nolte, E. Learning for the NHS on procurement and supply chain management: A rapid evidence assessment. Health Soc. Care Deliv. Res. 2014, 2, 25642568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H.C.; Hori, Y.; Revill, P.; Rattanavipapong, W.; Arai, K.; Nonvignon, J.; Jit, M.; Teerawattananon, Y. Analyses of the return on investment of public health interventions: A scoping review and recommendations for future studies. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e012798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health. The National Model of Care; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health. Model of Care Interventions of System of Care: Revised MOC Elements/Interventions MOC 1.1 Version 2.0; 2025; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Timmins, N.; Ham, C. The Quest for Integrated Health and Social Care: A Case Study in Canterbury, New Zealand; Kings Fund: Canterbury, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail, in Museum Management and Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, J.M.; Smith, M.; Saunders, R.; Stuckhardt, L.; McGinnis, J.M. (Eds.) Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America; National Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health. Statistical Yearbook 2023; Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Porter, M.E. What is value in health care? N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2477–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwick, D.M.; Nolan, T.W.; Whittington, J. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Population, Total—Saudi Arabia. World Development Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=SA (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. 2022. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT). Population Estimates 2022. Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 2022. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.sa (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ahmad, T. Diabetes in Saudi Arabia: A growing public health challenge. J. Diabetol. 2024, 15, 456–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rubeaan, K.; Al-Manaa, H.A.; Khoja, T.A.; Ahmad, N.A.; Al-Sharqawi, A.H.; Siddiqui, K.; Alnaqeb, D.; Aburisheh, K.H.; Youssef, A.M.; Al-Batel, A.; et al. Epidemiology of abnormal glucose metabolism in a country facing its epidemic: SAUDI-DM study. J. Diabetes 2015, 7, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattan, W.; Alshareef, N. 2022 insights on hospital bed distribution in Saudi Arabia: Evaluating needs to achieve global standards. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From triple to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, B.G.; Spivack, B.S.; Stearns, S.C.; Song, P.H.; O’Brien, E.C. Impact of accountable care organizations on utilization, care, and outcomes: A systematic review. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2019, 76, 255–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindul-Rothschild, J.; Gregas, M. Patient turnover and nursing employment in Massachusetts hospitals before and after health insurance reform: Implications for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Policy Politics Nurs. Pract. 2013, 14, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, J.H.; Borowski, A. Long-term care insurance reform in Singapore. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2022, 34, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, A.; Greenhalgh, T.; Lewis, S.; Saul, J.E.; Carroll, S.; Bitz, J. Large-system transformation in health care: A realist review. Milbank Q. 2012, 90, 421–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, N.S.; Woodard, G.S.; Johnson, C.; Nguyen, J.K.; AlRasheed, R.; Song, F.; Stoddard, S.; Mugisha, J.C.; Sievert, K.; Dorsey, S. Stakeholder engagement to inform evidence-based treatment implementation for children’s mental health: A scoping review. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2022, 3, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Intervention Name (Official) | System of Care Association | Source (MoH Document) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Cutting (15) | Health in All Policies | All | 2017 Overview; 2025 V2.0 Annex C |

| School Education Programs | All | 2017 Overview | |

| Virtual Education and Navigation Tools | All | 2017 Overview | |

| Healthy Living Campaigns | All | 2017 Overview | |

| Health Hotline Services | All | 2017 Overview | |

| Enhanced Home Care Services | All | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Enhanced Primary Care Services | All | 2025 V2.0 | |

| National Referral Networks | All | 2017 Overview | |

| Integrated Personal Health Records | All | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Systematic Data Collection | All | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Outcomes Monitoring | All | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Resource Optimization | All | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Health Research Programs | All | 2017 Overview | |

| National Guidelines | All | 2017 Overview | |

| Virtual Self-Care Tools | All | 2025 V2.0 | |

| System-Specific (27) | Health Coach Program | Keep Well | 2017 Overview |

| Community-Based Wellness Programs | Keep Well | 2017 Overview | |

| Workplace Wellness Programs | Keep Well | 2017 Overview | |

| School Wellness Programs | Keep Well | 2017 Overview | |

| Healthy Food Promotion | Keep Well | 2017 Overview | |

| Health Edutainment Programs | Keep Well | 2017 Overview | |

| Promoting the Saudi CDC | Keep Well | 2025 V2.0 | |

| One-Stop Clinics | Planned Procedure | 2017 Overview | |

| Pathway Optimization | Planned Procedure | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Length of Stay Reduction Initiatives | Planned Procedure | 2017 Overview | |

| Step-Down and Post-Discharge Services | Planned Procedure | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Resource Control Center | Urgent Problem | 2017 Overview | |

| Urgent problem Clinics | Urgent Problem | 2017 Overview | |

| Population-Based Critical Care Centers | Urgent Problem | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Premarital Screening | Safe Birth | 2017 Overview | |

| Preconception Care Services | Safe Birth | 2017 Overview | |

| Safe Birth Services | Safe Birth | 2017 Overview | |

| National Birth Registry | Safe Birth | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Postnatal Care Services | Safe Birth | 2017 Overview | |

| Well Baby Clinics | Safe Birth | 2017 Overview | |

| Neonatal Care Services | Safe Birth | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Chronic Disease Screening | Chronic Condition | 2017 Overview | |

| Case Coordination | Chronic Condition | 2017 Overview | |

| Continuing Care Services | Chronic Condition | 2025 V2.0 | |

| Patient and Family Support | Last Phase of Life | 2017 Overview | |

| Hospice Care Services | Last Phase of Life | 2017 Overview | |

| Multidisciplinary Team Development | Last Phase of Life | 2025 V2.0 |

| Region/Clusters | Estimated Population (Millions) | Bed Density (per 1000) | Urban/Rural Coverage | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riyadh Province—3 clusters | ~8.2 | 2.8–3.5 | Predominantly Urban | Capital region; high chronic disease burden |

| Makkah Province—3 clusters | ~7.0 | 2.5–2.8 | Urban/Rural Mix | Seasonal Hajj/Umrah surge |

| Eastern Province—2 clusters | ~3.2 | 3.0–3.2 | Predominantly Urban | Industrial and occupational health risks |

| Al-Qassim Province—1 cluster | ~1.0 | ~2.2 | Mixed | Agricultural region |

| Madinah Province—1 cluster | ~2.3 | ~2.5 | Urban/Rural Mix | Religious tourism |

| Hail Province—1 cluster | ~0.74 | ~2.0 | Mixed | Mountain/desert terrain |

| Tabuk Province—1 cluster | ~0.88 | ~2.1 | Mixed | Border security considerations |

| Al-Jouf Province—1 cluster | ~0.60 | ~2.3 | Predominantly Rural | Remote access challenges |

| Northern Borders—1 cluster | ~0.37 | ~1.5 | Predominantly Rural | Harsh desert climate |

| Asir Province—1 cluster | ~2.1 | ~2.7 | Urban/Rural Mix | Mountainous geography |

| Najran Province—1 cluster | ~0.50 | ~1.8 | Predominantly Rural | Border area |

| Jazan Province—1 cluster | ~1.4 | ~2.4 | Mixed | Coastal and agricultural |

| CFIR Domain | Saudi MoC Elements Related to the Domain | Baseline Values (Examples) |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention Characteristics | Detailed specification of 42 interventions providing clarity. Articulation of relative advantages (projected financial savings and health outcome improvements). Design includes adaptability for different contexts (geographic, special populations). Comprehensive documentation (e.g., 2017 MoC Overview, 2025 V2.0 Interventions) indicating design quality and packaging. | Baseline life expectancy: 74 years (2016), with a target of 80 years by 2030 [13,14,16]; Baseline NCD mortality: 73% of deaths (2016), with a target reduction through prevention to <10% probability of premature mortality by 2030 [7,15,16,23,24,25]. |

| Outer Setting | Alignment with patient needs and expectations (structured around “Six Asks”). Responsiveness to external policies and mandates (explicit link to Saudi Vision 2030). Consideration of broader healthcare trends (implied response to global calls for transformation). | Baseline population: ~32.18 million (2022 census); projected growth to ~34.6 million by 2025 [26,27,28]; Baseline chronic disease prevalence high (e.g., diabetes ~18.5%), target improved management via Vision 2030 [29,30]. |

| Inner Setting | Planned structural changes (e.g., Cluster governance, National Referral Networks). Focus on networks and communications (e.g., Integrated PHR, e-referral platforms). Aim to influence organizational culture (shift towards prevention, patient activation, team-based care). Consideration of implementation climate (planned resource allocation, future value-based incentives). Emphasis on readiness for implementation (leadership engagement, capability building programs). | Baseline hospital beds: Approximately 2.43 beds per 1000 population [31], target optimization via cluster reforms [16]; Baseline primary care utilization: Low (~20% of visits), target increase to gatekeeping role. |

| Characteristics of Individuals | Addressing knowledge and beliefs through training and development components. Building self-efficacy via capability building initiatives for staff. Acknowledging individual stage of change through a dedicated change management strategy. | workforce density: the physician workforce density in Saudi Arabia reached approximately 3.5 physicians per 1000 population, reflecting progress from earlier baseline levels, with Vision 2030 targeting further capacity-building and expanded professional roles [16,22]. |

| Implementation Process | Formal planning process (outlined five-step approach). Engaging stakeholders (co-creation approach mentioned in initial design, ongoing communication emphasized). Structured execution strategy (phased rollout across clusters, prioritization of interventions). Mechanisms for reflecting and evaluating (Systematic Data Collection, Outcomes Monitoring, specific performance metrics in V2.0). | Primary health care (PHC) centers recorded over 100 million visits, with a steady increase compared to previous years (e.g., 15% rise from 2022), indicating improved access and capacity building [22]. Virtual consultations reached 50 million, including 20 million via the 937 hotline, 15 million through the Seha app (https://www.seha.sa/), and additional services via the X platform for prescriptions and consultations. Mobile clinic visits exceeded 5 million, supporting community-based care. Referrals totaled 2.5 million, facilitating integrated pathways. Home medical care services provided care to 1.2 million patients, reducing hospital burdens [22]. Virtual appointments numbered 30 million, enhancing timeliness. Average hospital length of stay was 4.5 days (down from 5.2 in 2022), and ICU stay averaged 3.8 days (down from 4.1), reflecting optimized resource use and efficiency gains with target reduction via phased metrics [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aljerian, N.A.; Almasud, A.M.; AlQahtani, A.; Alyanbaawi, K.K.; Almutairi, S.F.; Alharbi, K.A.; Alshahrani, A.A.; Albadrani, M.S.; Alabdulaali, M.K. Exploring a Systems-Based Model of Care for Effective Healthcare Transformation: A Narrative Review in Implementation Science of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Experience. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192453

Aljerian NA, Almasud AM, AlQahtani A, Alyanbaawi KK, Almutairi SF, Alharbi KA, Alshahrani AA, Albadrani MS, Alabdulaali MK. Exploring a Systems-Based Model of Care for Effective Healthcare Transformation: A Narrative Review in Implementation Science of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Experience. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192453

Chicago/Turabian StyleAljerian, Nawfal A., Anas Mohammad Almasud, Abdulrahman AlQahtani, Kholood Khaled Alyanbaawi, Sumayyah Faleh Almutairi, Khalaf Awadh Alharbi, Aisha Awdha Alshahrani, Muayad Saud Albadrani, and Mohammed K. Alabdulaali. 2025. "Exploring a Systems-Based Model of Care for Effective Healthcare Transformation: A Narrative Review in Implementation Science of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Experience" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192453

APA StyleAljerian, N. A., Almasud, A. M., AlQahtani, A., Alyanbaawi, K. K., Almutairi, S. F., Alharbi, K. A., Alshahrani, A. A., Albadrani, M. S., & Alabdulaali, M. K. (2025). Exploring a Systems-Based Model of Care for Effective Healthcare Transformation: A Narrative Review in Implementation Science of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Experience. Healthcare, 13(19), 2453. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192453