Nurse Midwives’ Perspectives on Women’s Vocalization During the First and Second Stages of Labor: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Obstetric Characterization

3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

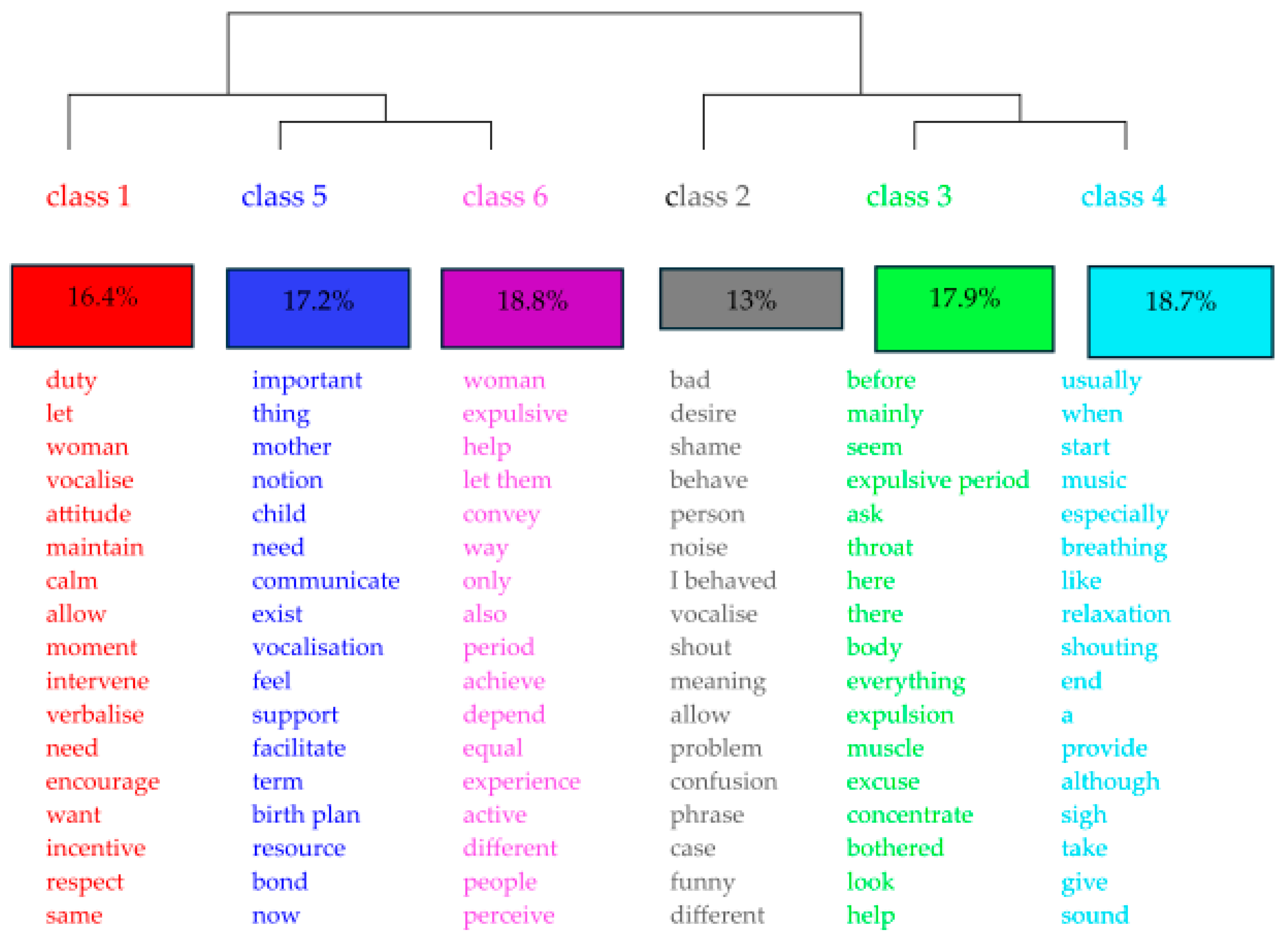

3.3. Thematic Classes

“I don’t think we should intervene in that… we should allow it”(int_03)

“I encourage women if they feel the need to express themselves vocally, I always encourage them”(int_09)

“I think it’s a waste of resources and energy on the part of the pregnant woman, who could be focusing her attention on breathing effectively to help minimize the pain of contractions.”(int_06)

“You still see some women who are ashamed to scream or draw attention to themselves, perhaps because they don’t want to behave badly”(int_11)

“There are women who do not feel comfortable vocalizing, and when they do so involuntarily… they apologize… they feel… ashamed… during the expulsion phase… they do not feel well… they are in labor… when they come to their senses, they apologize… because they feel ashamed.”(int_03)

“It’s allowing them, telling them that it’s okay to scream as much as they want… allowing them to vocalize.”(int_13)

“I’m not in the habit of saying ‘look, scream’ or ‘open your mouth’. I’m not ready for that yet, nor am I aware of it… to make the woman feel comfortable doing it, but maybe it’s more because I don’t know… I don’t remember that it can be a tool for her.”(int_10)

“They really scream, scream, we know it bothers us, but I notice that it bothers me less. At the beginning of my practice, vocalization bothered me more than it does today.”(int_02)

“There is no need to encourage this, otherwise maternity will soon seem like a screaming competition.”(int_16)

“I think vocalizing helps them, especially during the expulsion period… also in the active phase, because when they vocalize, it helps to open the vagina due to the way they vocalize, the pressure exerted on the diaphragm is also reflected in the vagina”(int_03)

“Sometimes I even say, when I give the signal, start saying ‘a’ and sighing as if you want to let go, and they do that… I try to guide them in some way in this vocalization so that it is controlled and at a much lower tone, which is better for her, makes her relax, and is better for me”(int_05)

“Because she is disoriented and out of control, not in the active phase, I don’t encourage it. Sometimes I even tell women that if they want to scream, they should scream, but not in an uncontrolled way… when they are in the expulsion phase… if they want to scream, they should scream.”(int_12)

“There may be some extreme screaming, I don’t think that has ever happened, but if it does, you have to understand that it’s not because she’s screaming louder that it’s going to relieve her pain. You have to understand and try other means, such as relaxation, breathing, exercises, listening to music, but without exaggeration.”(int_07)

“Breathing in and filling your chest with air and then breathing out slowly through your mouth while pushing is more effective because it is a sustained force, as the woman concentrates on that breathing and can hear the specialist nurse… in fact, it helped a lot, she didn’t scream, she breathed very effectively and pushed at the right moment, at the right time and for the right amount of time.”(int_06)

“I think it’s natural, and women used to do it in the old days, so maybe it really is beneficial for labor”(int_04)

“Vocalization is an important way for people to express what they are feeling”(int_16)

“When we hear them vocalize, some expressions, we know if they are in pain, if they need something”(int_08)

“If a woman is vocalizing, it is to relieve pain”(int_09)

“They hear their mother’s vocalization, they hear the voice they already heard in the womb… it is the continuation of the mother-child relationship that already existed”(int_02)

“Sometimes things are a little difficult, and they open their mouths and vocalize, and that seems to help a little, and they gain strength and energy to expel”(int_10)

“The different forms of vocalization help to open the vagina”(int_03)

“Sometimes I think we need to bring them… back to reality, because sometimes we need them to do certain things to check the well-being of the fetus, but other than that… they can vocalize”(int_04)

“We end up understanding better how patients feel and what their needs are”(int_02)

“In the expulsion phase, it’s the same thing, because in the expulsion phase we can also understand a little about their reactions, how they view childbirth and not only that, but also birth, how receptive they are to receiving the newborn, their child”(int_01)

“They don’t need to say words about what they are feeling; their expressions and what we hear are important so that we can perhaps know the best way to act in the active phase of the expulsion period. It’s the same thing.”(int_08)

“Vocalization… conveys the moment… it can be a vocalization of well-being… and it can be distressing, asking for help… and we try to help”(int_02)

“They also convey a little of what they are feeling in terms of pain and not only that; sometimes even fear, other times other needs they have in relation to the active phase”(int_01)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Incorporating curriculum modules on vocal physiology, toning techniques, prenatal singing, and clinical listening into obstetrics programs;

- Standardizing environmental adjustments for acoustic privacy and advance information for the family;

- Developing clinical language guidelines, replacing prescriptive directives with non-directive support techniques.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DHC | Descending hierarchical classification |

| ECUs | Elementary context units |

| ICUs | Initial context units |

| IraMuTeQ | Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ULSAALE | Unidade Local de Saúde do Alto Alentejo |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

- −

- What do you think about the use of vocalization by women in active labor? (Class 6, Class 3)

- −

- What do you think about the use of vocalization by women in labor during the expulsion phase? (Class 6, Class 3)

- −

- Do you believe in vocalization as a skill for women in labor? (Class 5)

- −

- What kind of support did you offer women who vocalized? (Class 1)

- −

- Are you aware of the expectations of women in labor regarding the use of vocalization during the active and expulsion stages of labor? (Class2)

- −

- What is your attitude toward women who use vocalization during the active stage of labor? (Class 3, Class 4))

- −

- What is your attitude toward women who vocalize during the expulsion stage of labor? (Class 3, Class4)

- −

- What is your attitude toward women who are unable to vocalize on their own during the active stage of labor? (Class1)

- −

- What is your attitude toward women who are unable to vocalize on their own during the expulsion stage of labor? (Class1)

- −

- In addition to your personal experience in assisting women in labor, are you familiar with any models or theories, or have you read any scientific articles on vocalization during labor? (Class1)

- −

- What resources have you used to enable women in labor to vocalize? (Class 1)

- −

- How do you encourage vocalization to create the bond between mother and child? (Class 5)

Appendix B

| Class Number | Class Name | ECUs | % | Representative Words | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attitude toward vocalization | 43 | 16.4% | duty, leave, woman, vocalize, attitude, maintain, calm, allow, moment, intervene, verbalize, need, encourage, want, incentive, respect, equal | “My attitude is somewhat expectant, letting things happen, always trying to intervene as little as possible” (int_11) |

| 2 | Significance of women’s self-image | 34 | 13% | bad, desire, shame, behave, person, noise, I behaved, vocalize, shout, meaning, allow, problem, confusion, sentence, case, funny, different | “They feel ashamed… they think that screaming or moaning… is bad behavior, and then they apologize… they feel guilty” (int_01) |

| 3 | Resistance and acceptance of vocalization | 47 | 17.9% | before, mainly, seem, expulsive period, ask, throat, here, there, body, everything, expulsion, muscle, excuse, concentrate, bothered, look, help | “During the expulsion period… this shout helps with the expulsion… only at the moment of expulsion… shouting before doesn’t help much” (int_12) |

| 4 | Control and inhibition of vocalization | 49 | 18.7% | normally, when, begin, music, especially, breathe, as, relaxation, shout, finish, one, provide, although, sigh, take, give, sound | “I also love deliver babies to the sound of music. When there is no soundtrack, I usually turn on the radio, and when they start to lose control, I say, ‘Look, get into the rhythm of the music’ (int_05). |

| 5 | Advantages and disadvantages of vocalization | 45 | 17.2% | important, thing, mother, notion, child, need, communicate, exist, vocalization, feel, support, facilitate, term, birth plan, resource, bond, now | “Vocalization is an important way for people to express what they are feeling” (int_16) |

| 6 | The usefulness of vocalization in caregiving | 44 | 16.8% | woman, expulsive, help, let them, convey, way, just, also, period, achieve, depend, equal, experience, active, different, people, perceive | “Vocalization… also helps nurse midwives interpret how the woman is experiencing labor” (int_02) |

References

- Rabinerson, D.; Horowitz, E. The evolution of midwifery. Harefuah 2007, 146, 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, C.L.; McKenzie, B.; Hauck, Y. Looking Back Moving Forward: The History of Midwifery in Western Australia. Women Birth 2022, 35, e409–e420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Švaljug, D.; Malnar, D.; Kurbanovič, M.; Kuljak, Ž.; Bonačić, D. A History of the Midwifery Profession in the Republic of Croatia. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2022, 33, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, J. What Role Does Gender Have in Shaping Knowledge That Underpins the Practice of Midwifery? J. Gend. Stud. 2019, 28, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, B.F.; Roberts, J.E.; McKay, S. Acoustical analysis of maternal sounds during the second stage of labor. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1993, 6, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, S.; Roberts, J. Obstetrics by ear: Maternal and caregiver perceptions of the meaning of maternal sounds during second stage labor. J. Nurse Midwifery 1990, 35, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikin, A.; Canessa-Pollard, V.; Pisanski, K.; Massenet, M.; Reby, D. Beyond Speech: Exploring Diversity in the Human Voice. iScience 2023, 26, 108204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikin, A.; Persson, T.; Arnling Bååth, R. Human Non-Linguistic Vocal Repertoire: Call Types and Their Meaning. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2018, 42, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, J.; Pisanski, K.; Reby, D. Tennis Grunts Communicate Acoustic Cues to Sex and Contest Outcome. Anim. Behav. 2017, 130, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W. “The Luxurious Daughters of Artificial Life”: Female “Delicacy” and Pain in Late-Victorian Advice Literature. Can. Bull. Med. Hist. 2014, 31, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinsser, L.A.; Stone, N.I. Overcoming Shame to Vocalise During Childbirth: A Qualitative Interview Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosen, M.; Tavčar Krajnc, M. Sociological Conceptualization of the Medicalization of Pregnancy and Childbirth: The Implications in Slovenia. Rev. Sociol. 2013, 43, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colmenares, J.; Ramírez, B. Let’s go back to humanized childbirth. Rev. Obstet. Ginecol. Venez. 2024, 84, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, D.M. “To Change the World, We Must First Change the Way the Babies Are Being Born”: Childbirth Activism in Europe. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosevelt, L.; Danford, K.; Zielinski, R. Impolite Birth: Provider Perspectives on Vocalization During Childbirth. Birth 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.; Nucci, M.; Silva, F.L.; Chazan, L.K. Climbing volcanoes: Rereading pain in humanized childbirth. Mana Estud. Antropol. Soc. 2019, 25, 519–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Kenner, A.N. Communication of Pain: Vocalization as an Indicator of the Stage of Labour. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1993, 33, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Mendonça, P.P.; Vieira, L.B.; Silva, V.L.; Zveiter, M. The Use of Your Own Voice in Labor: A Phenomenological Study. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2023, 43, e20220215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danford, K.; Mercein, J. The Birth Process and Voice Training: The Glorious Chorus: A Qualitative Pilot Inquiry. Voice Speech Rev. 2017, 12, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danford, K.; Roosevelt, L.; Vroom, A.; Harris, L.; Zielinski, R. Impolite Birth: Theatre Voice Training and the Experience of Childbirth. Voice Speech Rev. 2022, 17, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverly Pierce The practice of toning in pregnancy and labour: Participant experiences. Complement. Ther. Nurs. Midwifery 1998, 4, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Neta, J.N.; Amorim, M.M.; Guendler, J.; Delgado, A.; Lemos, A.; Katz, L. Vocalization during the Second Stage of Labor to Prevent Perineal Trauma: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 275, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppänen, T. Always More Than Two: Vibrations, the Foetus, and the Pregnant Person in Childbirth Singing Practices. NORA-Nord. J. Fem. Gend. Res. 2018, 26, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Foster, B.M. “No Justice in Birth”: Maternal Vanishing, VBAC, and Reconstitutive Practice in Central Florida. Am. Anthropol. 2023, 125, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, D.; Magnard, C.; Koutseff, A.; Patural, H.; Chauleur, C.; Reby, D.; Pisanski, K. Vocal Communication and Perception of Pain in Childbirth Vocalizations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2025, 380, 20240009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Waal, R.; Mayra, K. Obstetric Violence. In Gender-Based Violence: A Comprehensive Guide; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 413–425. ISBN 978-303105640-6. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D. Midwives, Gender Equality and Feminism. Pract. Midwife 2016, 19, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Dayyabu, A.L.; Murtala, Y.; Grünebaum, A.; McCullough, L.B.; Arabin, B.; Levene, M.I.; Brent, R.L.; Monni, G.; Sen, C.; Makatsariya, A.; et al. Midwife-Assisted Planned Home Birth: An Essential Component of Improving the Safety of Childbirth in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Perinat. Med. 2019, 47, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggleton, S.; Davis, D. Applying Salutogenesis in Midwifery Practice. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 459–464. ISBN 978-303079515-3. [Google Scholar]

- Migliorini, L.; Setola, N.; Naldi, E.; Rompianesi, M.C.; Iannuzzi, L.; Cardinali, P. Exploring the Role of Birth Environment on Italian Mothers’ Emotional Experience during Childbirth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburas, R.; Pati, D.; Casanova, R.; Adams, N.G. The Influence of Nature Stimulus in Enhancing the Birth Experience. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2017, 10, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.-L.; Pan, W.-L.; Mu, P.-F.; Gau, M.-L. Birth Environment Interventions and Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Birth 2023, 50, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çamlibel, M. Experiences of Maternity Care: Is the Perspective of Health Care Professionals Respectful Care While That of Women Obstetric Violence?: A qualitative study. Medicine 2025, 104, e41467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, I.; Correia, M.; Sim-Sim, M.; Ferrão, A.C.; Zangão, M.O. Women’s Vocalization in the First and Second Stages of Labour: A Scoping Review Protocol. Women 2024, 4, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-4-155021-5.

- Rossato, M.; Martinez, A.M. Contribuições da metodologia construtivo-interpretativa na pesquisa sobre o desenvolvimento da subjetividade. Rev. Lusófona Educ. 2018, 40, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazoni, S.R.; de Carvalho, E.C.; dos Santos, C.B. Clinical Validation of the Nursing Diagnosis Labor Pain. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2013, 21, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Howson, A. Qualitative Research Methods (Sociology); Salem Press Encyclopedias: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Czakon, W.; Schmitt, F. Purposeful Sampling and Saturation in Qualitative Research Methodologies: Recommendations and Review. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.; Pradhan, S.; Ranajee. Sampling in Qualitative Research; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jian, M.; Muhamad, N.S.; Hizam-Hanafiah, M. Data saturation in qualitative research: Aliterature review in entrepreneurship study from 2004–2024. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and Justifying Sample Size Sufficiency in Interview-Based Studies: Systematic Analysis of Qualitative Health Research over a 15-Year Period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Cunha, M.P.; Meyer, V., Jr. Quantos participantes são necessários para um estudo qualitativo? Linhas práticas de orientação. Rev. Gest. Países Língua Port. 2019, 17, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havan, P.; Kohút, M. Details Matter: The Effect of Different Instructions and Their Order on the Bias of Measured Personality Traits by Social Desirability. Stud. Psychol. 2023, 65, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bispo Júnior, J.P. Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Health Research. Rev. Saude Publica 2022, 56, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Fundamentos de Pesquisa em Enfermagem—AVALIAÇÃO DE EVIDÊNCIAS PARA A PRÁTICA DA ENFERMAGEM, 9th ed.; Artmed Editora: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2018; ISBN 978-85-8271-489-8. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, K.M. Empirical Development of a Middle Range Theory of Caring. Nurs. Res. 1991, 40, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics João Marôco; ReportNumber, Lda: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Floyd, R. Obstetrics and Midwifery in the United States: The Tensions between the Technocratic and Midwifery Models of Maternity Care. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Reproductive Medicine and Technology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 56–69. ISBN 978-111984537-9. [Google Scholar]

- Badejoko, O.; Onwudiegwu, U. Management of Normal and Abnormal Labour. In Contemporary Obstetrics and Gynecology for Developing Countries, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 117–127. ISBN 978-303075385-6. [Google Scholar]

- Heera, K.C.; Parajuli, S.B.; Gurung, A.; Mishra, A. Respectful Maternity Care During Labour and Postpartum in a Tertiary Hospital: A Descriptive Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2024, 62, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivekanandan, K.; Sharma, U.; Sharma, B.; Raina, D. Respectful Maternal Care—Need for Educational Interventions Among Maternal Health Care Providers. ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 5899–5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkamu, E.; Tesfaye, G.; Yetwale, A. Provision of Respectful Maternity Care During Labor and Delivery and Associated Factors Among Postnatal Mothers at Jimma University Medical Center, Jimma, South West Ethiopia, 2021. Int. J. Childbirth 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stones, W. Respectful Care in Labour. Obstet. Gynaecol. Reprod. Med. 2016, 26, 341–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Lu, H.; Zang, Y.; Ren, L.; Li, C.; Wang, J. The Effects of Hands on and Hands off/Poised Techniques on Maternal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Midwifery 2020, 87, 102712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusambili, A.M.; Wisofschi, S.; Wade, T.J.; Temmerman, M.; Obure, J. A Qualitative Enquiry of Health Care Workers’ Narratives on Knowledge and Sources of Information on Principles of Respectful Maternity Care (RMC). PLOS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0000157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramme, T. Introduction. In Library of Ethics and Applied Philosophy; Springer Science and Business Media B.V.: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 35, pp. 1–14. ISBN 13876678. [Google Scholar]

- Nyoni, C.N.; Botma, Y. Implementing a Competency-Based Midwifery Programme in Lesotho: A Gap Analysis. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2019, 34, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangar, M.; Howe, J. How Discourses of Sharam (Shame) and Mental Health Influence the Help-Seeking Behaviours of British Born Girls of South Asian Heritage. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2021, 37, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. Women and Shame: Kin and Culture. In Feminism and Addiction; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 175–194. ISBN 978-131782307-0. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, O. Birthing Consciousness as a Case of Adaptive Altered State of Consciousness Associated with Transient Hypofrontality. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owren, M.J.; Amoss, R.T.; Rendall, D. Two Organizing Principles of Vocal Production: Implications for Nonhuman and Human Primates. Am. J. Primatol. 2011, 73, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, O.; Zibenberg, A.; Goldberg, A. Birthing Consciousness and the Flow Experience during Physiological Childbirth. Midwifery 2024, 138, 104151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernetskaya, N.I.; Shumovskaya, O.A. Providing Psychological Support to Pregnant Women in Childbirth by Obstetrician Service Staff. J. Obstet. Womens Dis. 2019, 68, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.T.; Ali, R.M.; Hussein, E.A. Effectiveness of an Educational Program on Nurses-Midwives’ Practices about Pain Management during Labor in Baghdad Maternity Hospitals. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2020, 14, 1866–1871. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M.; Goldkuhl, L.; Nilsson, C.; Wijk, H.; Gyllensten, H.; Lindahl, G.; Moberg, K.U.; Begley, C. Room4Birth-the Effect of an Adaptable Birthing Room on Labour and Birth Outcomes for Nulliparous Women at Term with Spontaneous Labour Start: Study Protocol for a Randomised Controlled Superiority Trial in Sweden. Trials 2019, 20, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, A.; Marinho, G.; Melo, R.S.; Pinheiro, F.; Lemos, A. Effectiveness of Breathing Exercises during First Stage of Labor: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2024, 68, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaviagem, A.; Melo Junior, E.; Lubambo, L.; Sousa, P.; Aragão, C.; Albuquerque, S.; Lemos, A. The Effectiveness of Breathing Patterns to Control Maternal Anxiety during the First Period of Labor: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2017, 26, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayres-de-Campos, D.; Louwen, F.; Vivilaki, V.; Benedetto, C.; Modi, N.; Wielgos, M.; Tudose, M.-E.P.; Timonen, S.; Reyns, M.; Yli, B.; et al. European Association of Perinatal Medicine (EAPM), European Board and College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (EBCOG), European Midwives Association (EMA). Joint Position Statement: Substandard and Disrespectful Care in Labour—Because Words Matter. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 296, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.; Lanceley, A.; Whitten, M.; Kelly, C.; Nicholls, J. Consent on the Labour Ward: A Qualitative Study of the Views and Experiences of Healthcare Professionals. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 264, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrão, A.; Zangão, M.; Almeida, V. Obstetric Violence Concept Analysis: Scoping Review; OSF: Peoria, IL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coxon, K.; Sandall, J.; Fulop, N.J. To What Extent Are Women Free to Choose Where to Give Birth? How Discourses of Risk, Blame and Responsibility Influence Birth Place Decisions. Health Risk Soc. 2014, 16, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbour, K. Home Birth vs. Hospital Birth. Voices Bioeth. 2016, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nattah, F.M.; AL-Yasir, A.A.; Khaleel, M.A. Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Program upon Midwives’ Knowledge Concerning Use of Partograph during First Stage of Labor in Al-Hilla Hospitals. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019, 10, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M.A.; Martin, C.R.; Dahlen, H.G. (R13596) Time to rectify past mistakes and take a woman-centred approach to labour progress. Obstet. Gynaecol. Reprod. Med. 2022, 32, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamichi, M. Non-Human Primate Birth and Human Birth. Primates J. Primatol. 2023, 64, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.E.S. A musicoterapia pré-natal; da criação de uma canção do bebé imaginário à observação da musicalidade comunicativa mãe-bebé após o nascimento. In FCSH: CESEM—Documentos de Conferências Nacionais; Repositorio Universidade Nova: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swee, G.; Schirmer, A. On the Importance of Being Vocal: Saying “Ow” Improves Pain Tolerance. J. Pain 2015, 16, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Menek, M.; Dansuk, E.; Tayboga, U.I. Effect of Local Vibration Therapy on Pain, Joint Position Sense, Kinesiophobia, and Disability in Cervical Disc Herniation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Chen, T. Om chanting modulates the processing of negative stimuli: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 943243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.P.; Alves, V.H.; e Silva, A.M.; Penna, L.H.G.; Vieira, B.D.G.; da Silva, S.É.D.; dos Reis, L.C.; Branco, M.B.L.R. Women’s Perception of Labor and Birth Care: Obstacles to Humanization. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2022, 75, e20210215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.; Etsane, E.; Bergh, A.-M.; Pattinson, R.; van den Broek, N. ‘I thought they were going to handle me like a queen but they didn’t’: A qualitative study exploring the quality of care provided to women at the time of birth. Midwifery 2018, 62, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Puyvelde, M.; Neyt, X.; McGlone, F.; Pattyn, N. Voice Stress Analysis: A New Framework for Voice and Effort in Human Performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus Batista, M.H.; Alves de Araujo, A.; Feitosa dos Santos, R.; Vicentino Lima, D.; Soares Nunes, T.; de Moraes Souza, A.C. Desafios da enfermagem frente ao parto humanizado: Percepções de profissionais sobre a humanização em obstetrícia. Saúde Coletiva 2021, 11, 6949–6955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, S. Paralinguistic profiling using speech recognition. Int. J. Speech Technol. 2014, 17, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Audhkhasi, K.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S. Detecting Paralinguistic Events in Audio Stream Using Context in Features and Probabilistic Decisions. Comput. Speech Lang. 2016, 36, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Audhkhasi, K.; Lee, S.; Narayanan, S. Paralinguistic event detection from speech using probabilistic time-series smoothing and masking. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2013, Lyon, France, 25–29 August 2013; pp. 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, H.; Samur, I.; Uzun, F.; Sahin, R. Cultural Methods Used by Women Who Give Vaginal Birth to Cope with Birth Labour Pain. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 13, 1988–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Prado, S.; Sánchez-Ojeda, M.; Marmolejo-Martín, J.; Kapravelou, G.; Fernández-Gómez, E.; Martín-Salvador, A. Cultural Influence on the Expression of Labour-Associated Pain. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susan, M. Culturally Sensitive Perinatal Care for Southeast Asians. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 1995, 24, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Code | Years as a Midwife | Age | Gender | Academic Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| int_01 | 19 | 57 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma |

| int_02 | 24 | 55 | Female | Master’s Degree |

| int_03 | 9 | 40 | Female | Master’s Degree |

| int_04 | 10 | 40 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma |

| int_05 | 18 | 49 | Female | Master’s Degree |

| int_06 | 2 | 38 | Male | Master’s Degree |

| int_07 | 18 | 56 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma |

| int_08 | 18 | 56 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma |

| int_09 | 1 | 42 | Female | Master’s Degree |

| int_10 | 18 | 56 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma |

| int_11 | 12 | 39 | Male | Master’s Degree |

| int_12 | 17 | 61 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma |

| int_13 | 16 | 52 | Female | Master’s Degree |

| int_14 | 17 | 56 | Male | Master’s Degree |

| int_15 | 6 | 38 | Female | Master’s Degree |

| int_16 | 19 | 59 | Female | Postgraduate Diploma |

| Variables | Categories | Frequencies n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Years as a nurse midwife | 0–5 years | 2 (12.50%) |

| 6–10 years | 4 (25.00%) | |

| 11–15 years | 1 (6.25%) | |

| 16–20 years | 9 (56.25%) | |

| Gender | Female | 13 (81.25%) |

| Male | 3 (18.75%) | |

| Geographical origin | Iberia | 16 (100%) |

| Religion | Christianity | 15 (93.75%) |

| Atheism | 1 (6.25%) | |

| Marital status | Married or civil union | 16 (100%) |

| Academic qualifications | Postgraduate Diploma in Maternal Health Nursing and Obstetrics Nursing | 7 (43.8%) |

| Master’s Degree in Maternal Health and Obstetrics Nursing | 9 (56.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, I.R.; Sim-Sim, M.; Zangão, M.O. Nurse Midwives’ Perspectives on Women’s Vocalization During the First and Second Stages of Labor: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192451

Pereira IR, Sim-Sim M, Zangão MO. Nurse Midwives’ Perspectives on Women’s Vocalization During the First and Second Stages of Labor: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192451

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Isabel Rute, Margarida Sim-Sim, and Maria Otília Zangão. 2025. "Nurse Midwives’ Perspectives on Women’s Vocalization During the First and Second Stages of Labor: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192451

APA StylePereira, I. R., Sim-Sim, M., & Zangão, M. O. (2025). Nurse Midwives’ Perspectives on Women’s Vocalization During the First and Second Stages of Labor: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(19), 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192451