Mapping Geographic Disparities in Healthcare Access Barriers Among Married Women in Pakistan: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Outcome Variable

2.2. Independent Variable

2.3. Data Management

2.4. Spatial Analysis

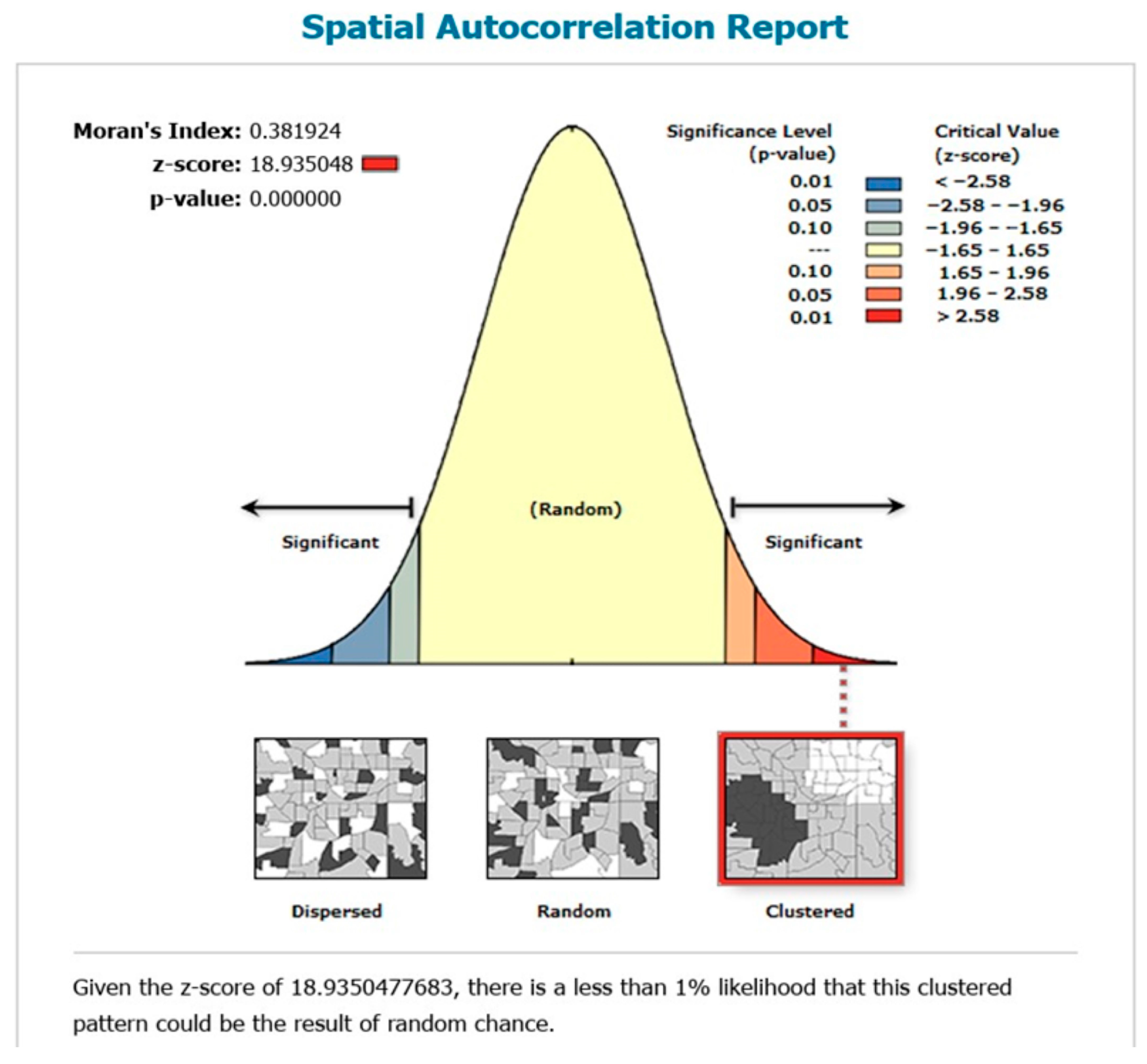

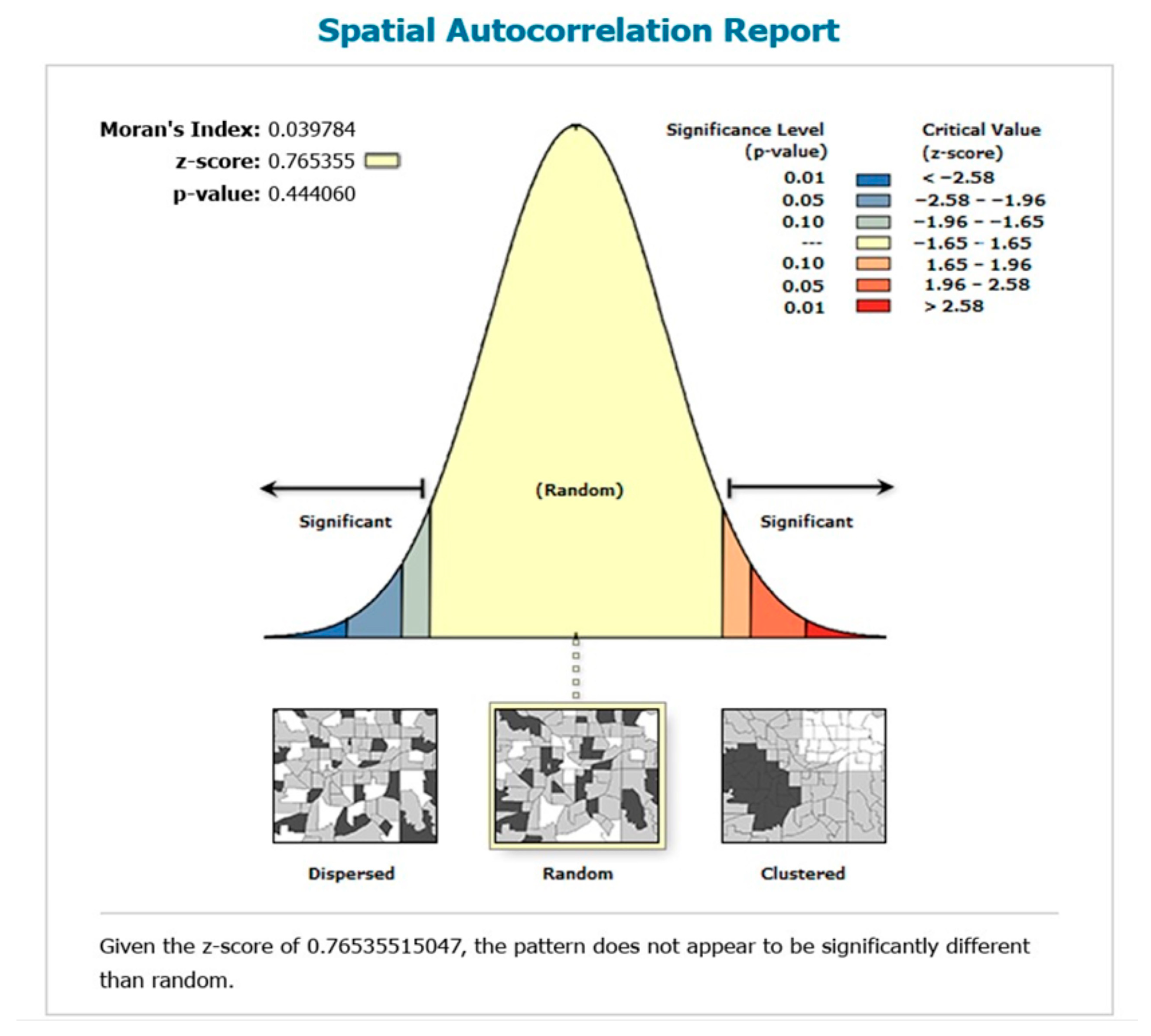

2.4.1. Spatial Autocorrelation

2.4.2. Local Moran’s I

2.4.3. Getis-Ord-Gi* Analysis

2.4.4. Spatial Scan Analysis

2.4.5. Spatial Interpolation

2.5. Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR)

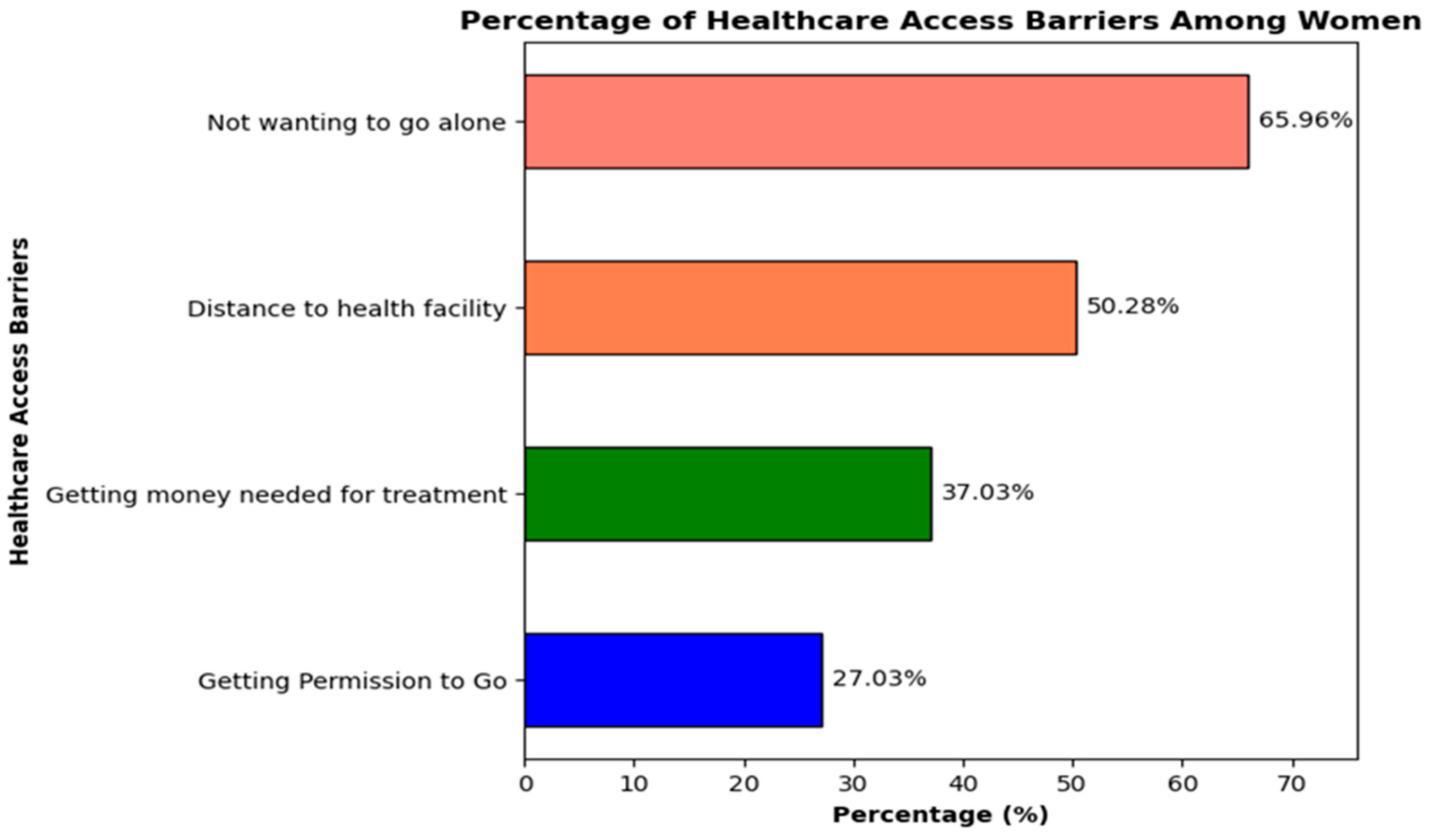

3. Results

3.1. Percentage Distribution of Characteristics of Respondents

3.1.1. Global Spatial Autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I) of Healthcare Access Barriers

3.1.2. Local Moran’s I Analysis of Healthcare Access Barriers

3.1.3. Getis-Ord-Gi* Analysis of Healthcare Access Barriers

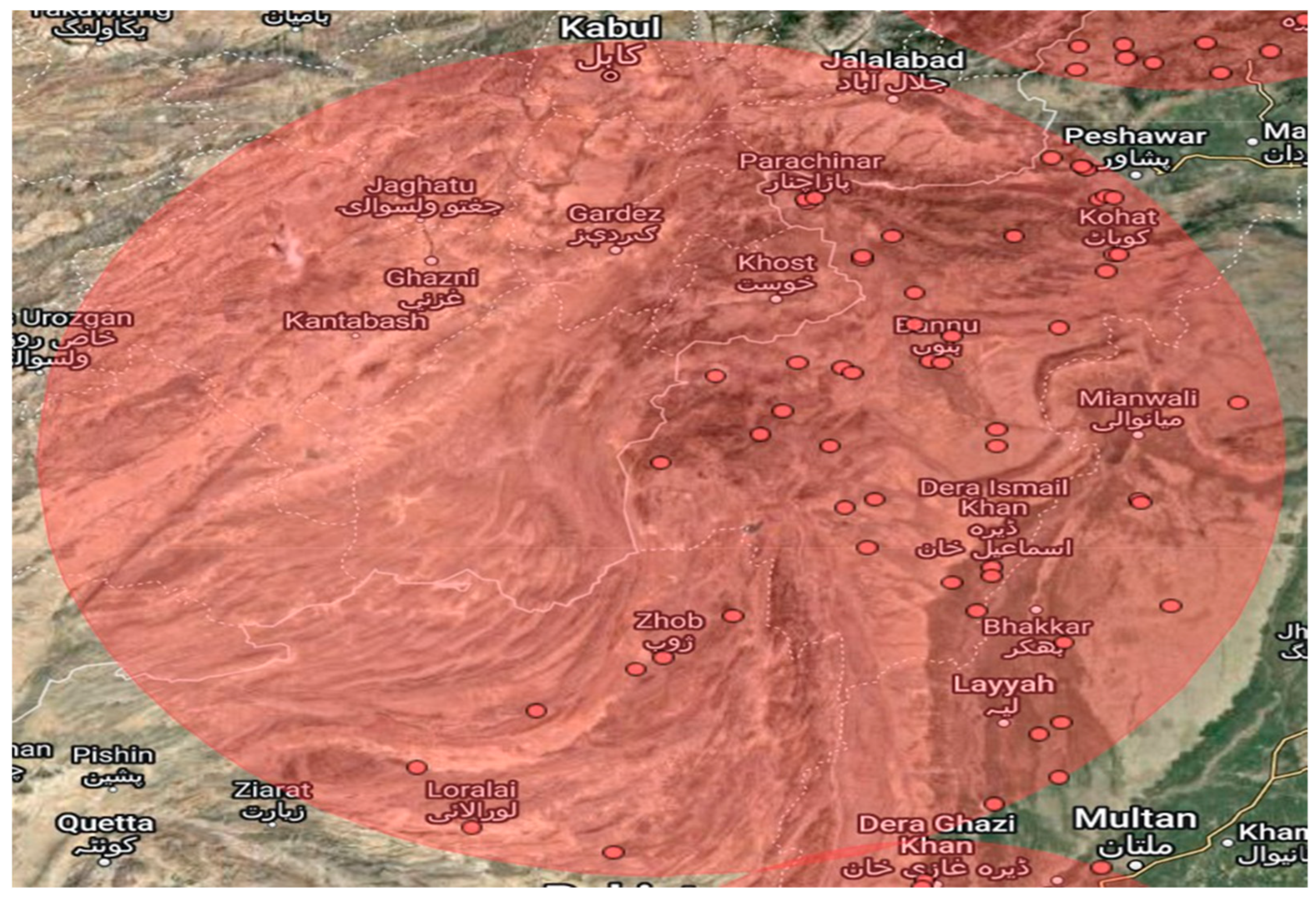

3.1.4. Spatial Scan Statistical Analysis of Healthcare Access Barriers

3.1.5. Spatial Interpolation Technique of Healthcare Access Barriers

3.2. Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) of Healthcare Access Barriers

3.2.1. Global Geographically Weighted Regression (GGWR) of Healthcare Access Barriers

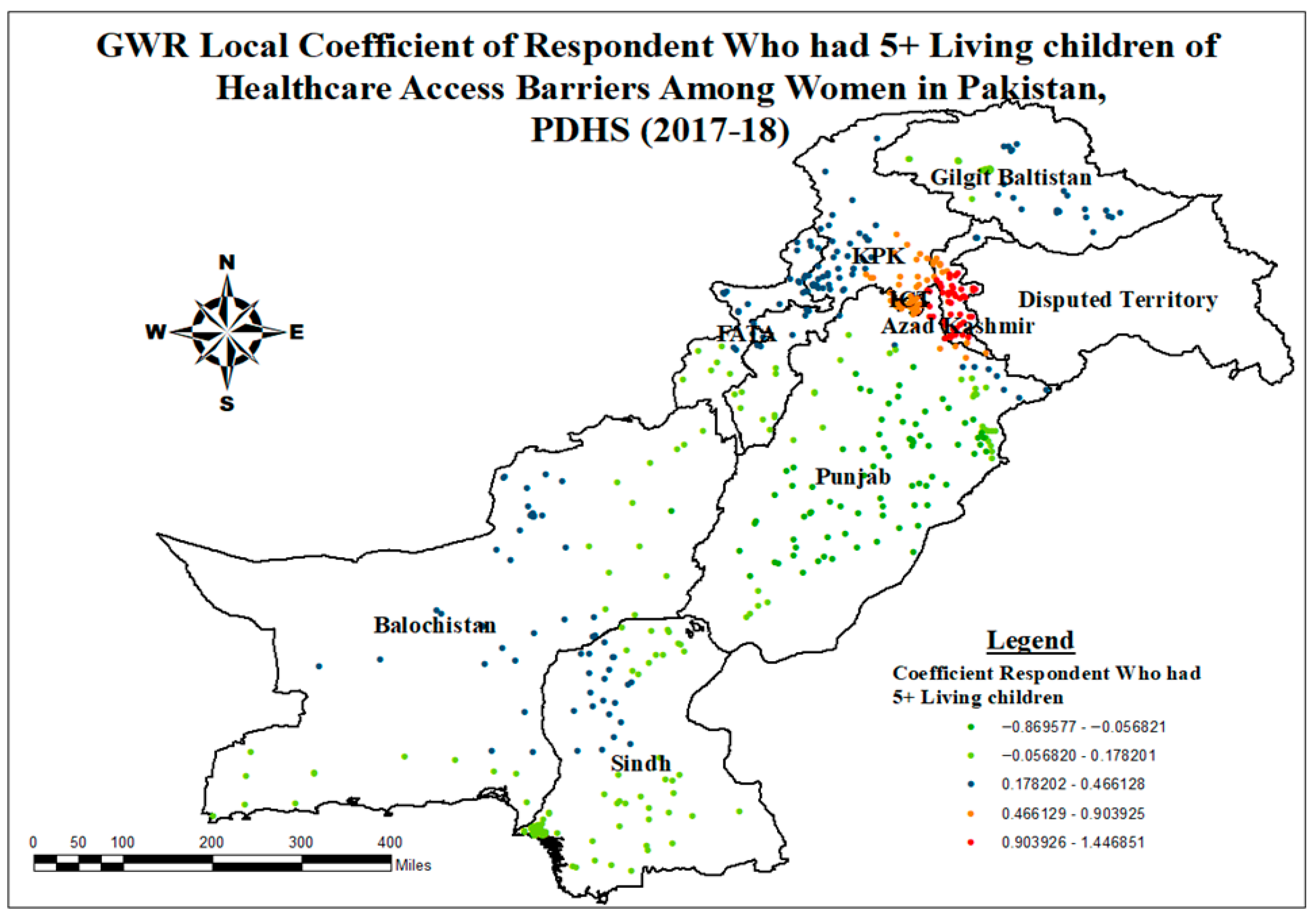

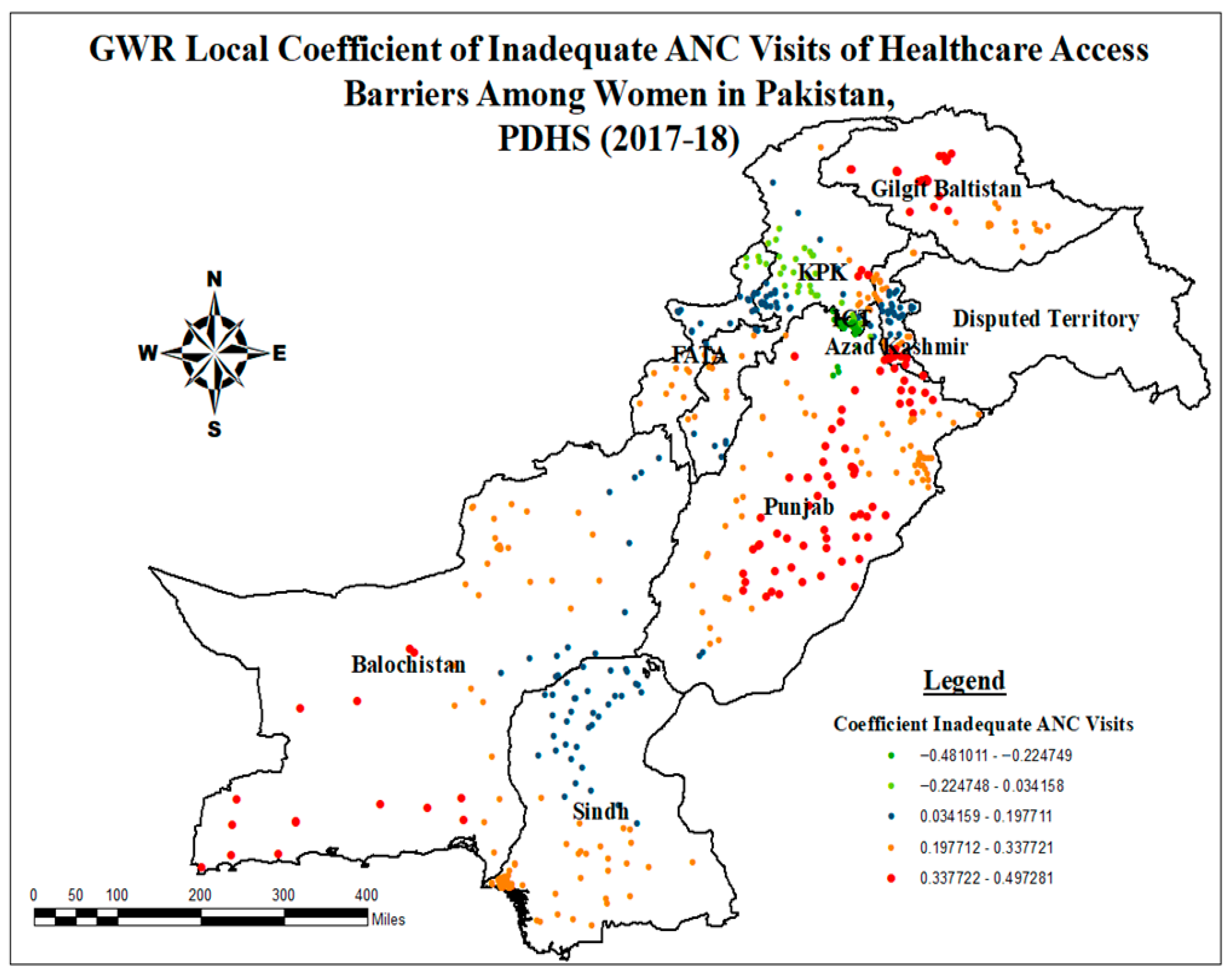

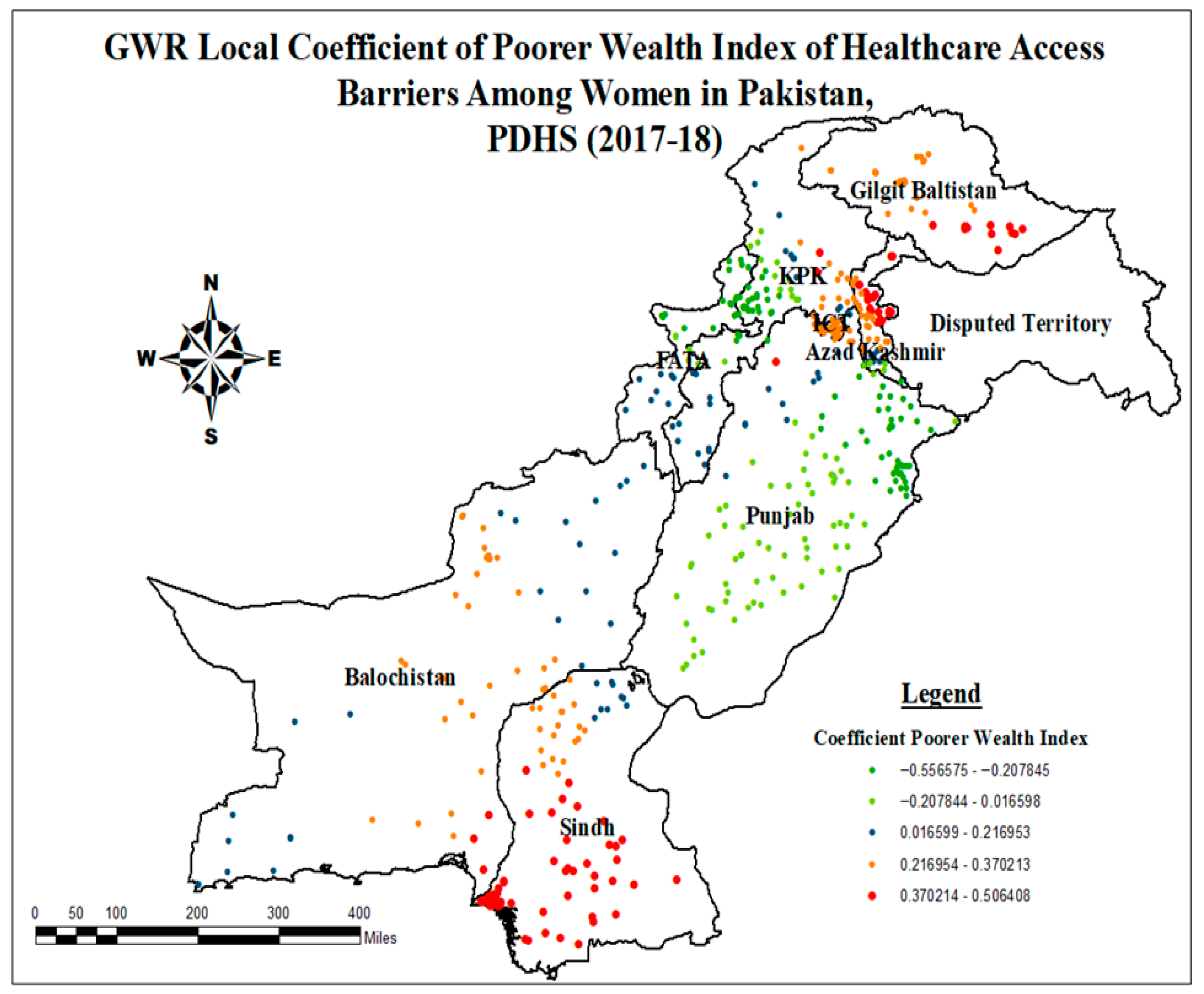

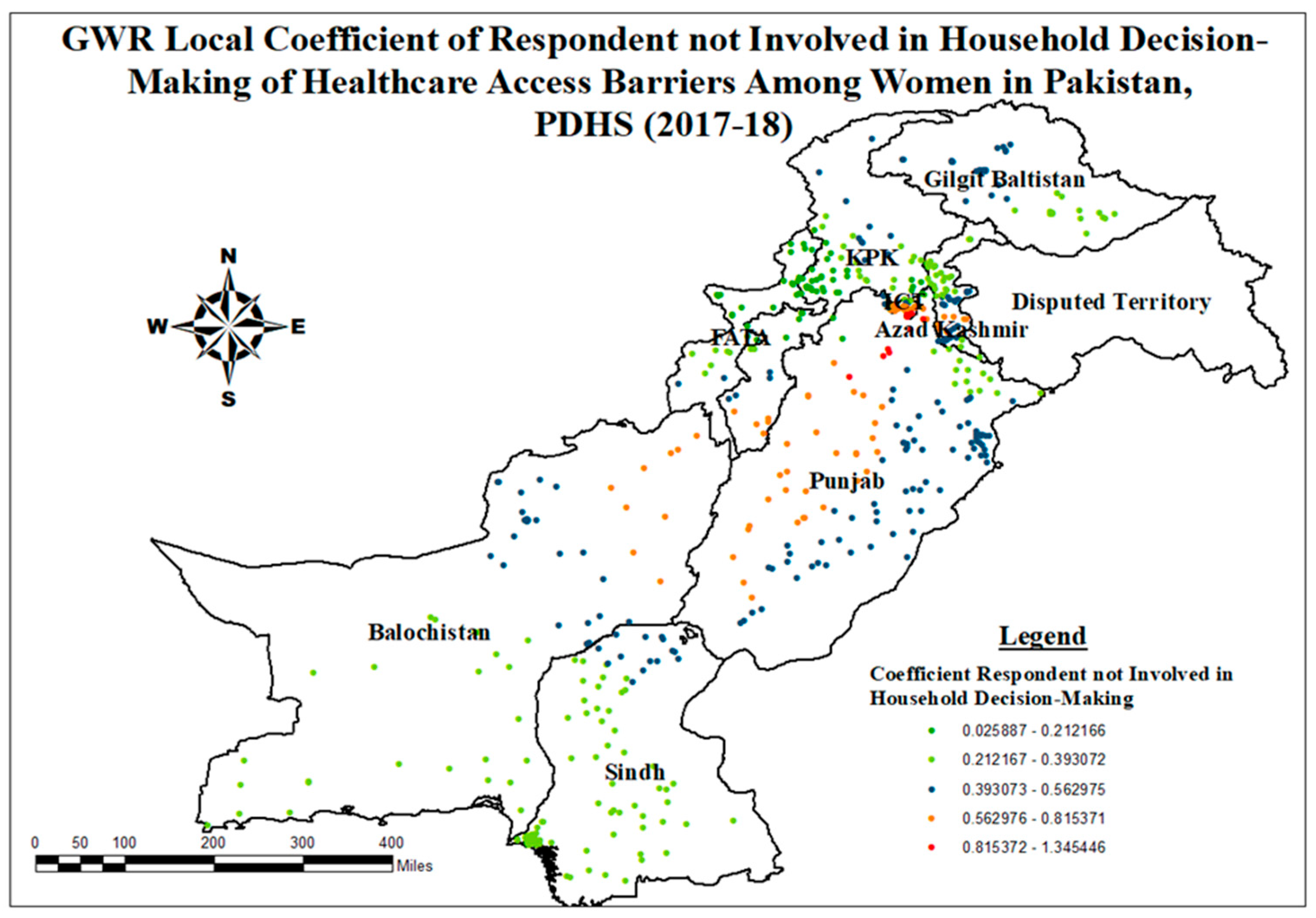

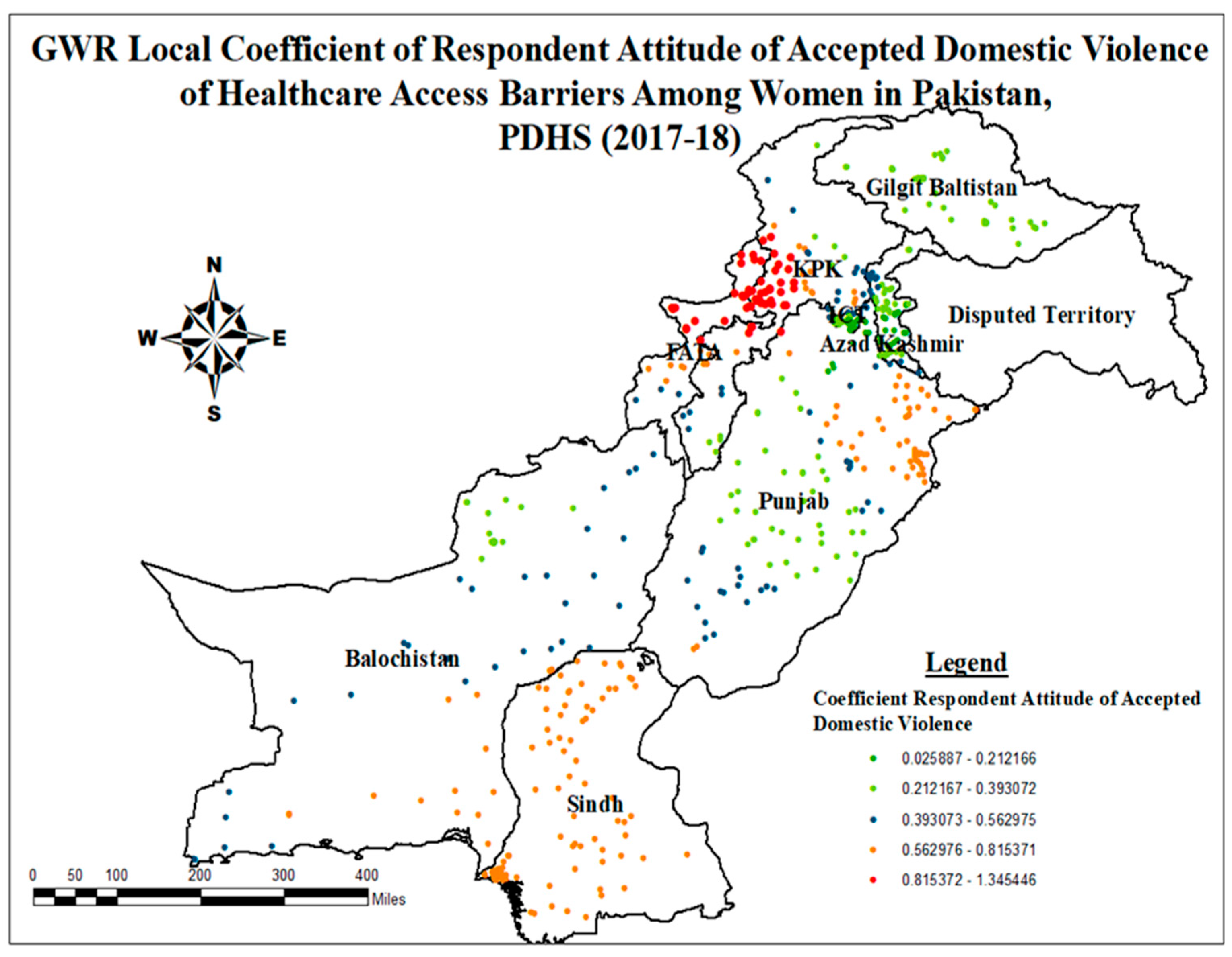

3.2.2. Local Geographically Weighted Regression (GGWR) of Healthcare Access Barriers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

7. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AJK | Azad Jammu Kashmir |

| ANC | Antenatal Care |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| BHU | Basic Health Units |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| EBK | Empirical Bayesian Kriging |

| FATA | Federally Administrated Tribal Areas |

| GB | Gilgit Baltistan |

| GGWR | Global Geographically Weighted Regression |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| GWR | Geographically Weighted Regression |

| ICT | Islamabad Capital Territory |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| KPK | Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

| LGWR | Local Geographically Weighted Regression |

| LR | Logistic Regression |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NB | Naïve Bayes |

| NHV | National Health Vision |

| NIPS | National Institute of Population Studies |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Square |

| PDHS | Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| PSU | Primary Sampling Unit |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RHC | Rural Health Centers |

| SBA | Skilled Birth Attendants |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| THQ | Tehsil Headquarter Hospitals |

| UHC | Universal Health Coverage |

| USA | United States of America |

| USAID | United Nations International Children |

| UTM | Universal Transverse Mercator |

| VIF | Variance Inflammation Factor |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Enumeration Blocks | Coordinates/Radius | Relative Risk | Percentage of Cases in Area | LLR | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 411, 412, 406, 408, 413, 83, 410, 84, 407, 409, 342, 79, 341, 75, 340, 74, 414, 76, 77, 78, 415, 72, 403, 404, 80, 81, 82, 338, 399, 401, 402, 400, 73, 111, 106, 405, 105, 339, 69, 70, 71, 107, 197, 198, 337, 98, 391, 336, 392, 395, 390, 397, 398, 393, 200, 201 | (32.423732 N, 69.429786 E)/257.96 km | 1.34 | 93.5 | 106.876263 | 0.000000 ** |

| 507, 474, 512, 511 | (35.515992 N, 74.517198 E)/38.11 km | 1.40 | 99.4 | 54.778603 | 0.000000 ** |

| 2, 4, 3, 1, 5, 6, 482, 12, 13, 481, 7, 384, 9, 387, 8, 388, 383, 10, 11, 17, 389, 14 | (35.891914 N, 71.726873 E)/156.20 km | 1.31 | 92.7 | 37.156954 | 0.000000 ** |

| 371, 370, 369, 368, 365, 356, 357, 367, 361, 364, 366, 378, 377, 373, 362, 360, 379, 358, 355, 372, 363, 380 | (27.760806 N, 64.515493 E)/299.89 km | 1.40 | 100.0 | 32.870359 | 0.000000 ** |

| 171, 170 | (30.803986 N, 73.460618 E)/18.69 km | 1.36 | 97.1 | 23.422738 | 0.000000 ** |

| 212, 211, 215, 195, 214, 213, 202, 199, 203, 194, 185, 180, 207, 182, 187, 193, 192, 204, 346, 186, 181 | (28.897297 N, 70.636209 E)/155.68 km | 1.18 | 83.3 | 21.363448 | 0.000001 ** |

| 315, 317, 236, 316, 318, 252 | (26.349390 N, 68.560090 E)/60.27 km | 1.25 | 89.1 | 12.397121 | 0.002914 * |

| 522, 517, 532, 516, 529, 519, 523, 518, 524, 534, 531, 520, 538, 521, 530, 515, 539, 26, 525, 537, 536, 22, 546, 553, 28, 550, 549, 90, 94 | (34.211114 N, 73.629460 E)/40.62 km | 1.16 | 82.6 | 11.402993 | 0.010000 * |

| 558 | (33.131774 N, 74.046401 E)/0 km | 1.40 | 100.0 | 10.681060 | 0.014000 * |

| 95, 562, 563 | (32.949536 N, 73.586231 E)/23.56 km | 1.26 | 90.3 | 7.567004 | 0.167000 |

| 319 | (25.736110 N, 69.247760 E)/0 km | 1.40 | 100.0 | 7.003788 | 0.262000 |

| 136, 112 | (31.884300 N, 73.341062 E)/26.33 km | 1.24 | 88.5 | 4.313667 | 0.968000 |

| 101, 102 | (32.322749 N, 72.920919 E)/19.36 km | 1.23 | 88.2 | 4.103052 | 0.980000 |

| 115 | (31.156356 N, 72.751577 E)/0 km | 1.26 | 90.0 | 4.047079 | 0.981000 |

| 576, 578, 577 | (33.474879 N, 74.074645 E)/15.16 km | 1.16 | 83.2 | 3.684936 | 0.997000 |

References

- Khan, S.U.; Hussain, I. Inequalities in Health and Health-Related Indicators: A Spatial Geographic Analysis of Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osadolor, O.; Aiseosa, O., Jr.; Osadolor, O.; Enabulele, E.; Akaji, E.; Odiowaya, D. Access to Health Services and Health Inequalities in Remote and Rural Areas. Janaki Med. Coll. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, A.; Roy, P. Applications of Geographical Information System and Spatial Analysis in Indian Health Research: A Systematic Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goal 3|Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3#targets_and_indicators (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Fang, J.; Tang, S.; Tan, X.; Tolhurst, R. Achieving SDG Related Sexual and Reproductive Health Targets in China: What Are Appropriate Indicators and How We Interpret Them? Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafree, S.R.; Shah, G.; Zakar, R.; Muzamill, A.; Ahsan, H.; Burhan, S.K.; Javed, A.; Durrani, R.R. Characterizing Social Determinants of Maternal and Child Health: A Qualitative Community Health Needs Assessment in Underserved Areas. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maternal Mortality Ratio (Modeled Estimate, per 100,000 Live Births)—Pakistan|Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT?locations=PK (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Rawal, L.B.; Paudel, M.; Howlader, M.H.; Khan, B.; Siddiquee, T.; Rahman, A.; Sarkar, A.; Rahman, M.S.; et al. Factors Influencing Place of Delivery: Evidence from Three South-Asian Countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Sultana, S.; Kundu, S.; Islam, M.A.; Roshid, H.O.; Khan, Z.I.; Tohan, M.; Jahan, N.; Khan, B.; Howlader, M.H. Trends and Patterns of Inequalities in Using Facility Delivery among Reproductive-Age Women in Bangladesh: A Decomposition Analysis of 2007-2017 Demographic and Health Survey Data. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e065674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliford, M.; Figueroa-Munoz, J.; Morgan, M.; Hughes, D.; Gibson, B.; Beech, R.; Hudson, M. What Does’ Access to Health Care’mean? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.E.; Carrillo, V.A.; Perez, H.R.; Salas-Lopez, D.; Natale-Pereira, A.; Byron, A.T. Defining and Targeting Health Care Access Barriers. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2011, 22, 562–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, K.; Carnahan, L.R.; Paulsey, E.; Molina, Y. Health Care Eligibility and Availability and Health Care Reform: Are We Addressing Rural Women’s Barriers to Accessing Care? J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthali, A.C.; Swartz, L.; Mannan, H.; MacLachlan, M.; Chilimampunga, C.; Makupe, C. “This One Will Delay Us”: Barriers to Accessing Health Care Services among Persons with Disabilities in Malawi. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, M.O.; Knight, L.; Dutton, J. Barriers to Accessing Maternal Health Care amongst Pregnant Adolescents in South Africa: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Allegheny County Health Department. Health Equity Brief Access to Health Care in Allegheny County; Allegheny County Health Department: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2018; Volume 5, pp. 2018–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sagna, M.L.; Sunil, T.S. Effects of Individual and Neighborhood Factors on Maternal Care in Cambodia. Health Place 2012, 18, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, A.J.; Guirlène Calixte, M. Effects of the Physical Accessibility of Maternal Health Services on Their Use in Rural Haiti. Popul. Stud. 2006, 60, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunil, T.S.; Rajaram, S.; Zottarelli, L.K. Do Individual and Program Factors Matter in the Utilization of Maternal Care Services in Rural India? A Theoretical Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1943–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockers, P.C.; Wilson, M.L.; Mbaruku, G.; Kruk, M.E. Source of Antenatal Care Influences Facility Delivery in Rural Tanzania: A Population-Based Study. Matern. Child Health J. 2009, 13, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotse-Gborgbortsi, W.; Nilsen, K.; Ofosu, A.; Matthews, Z.; Tejedor-Garavito, N.; Wright, J.; Tatem, A.J. Distance Is “a Big Problem”: A Geographic Analysis of Reported and Modelled Proximity to Maternal Health Services in Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.L.; Hall, J.A. Factors That Affect the Utilisation of Maternal Healthcare in the Mchinji District of Malawi. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.H.; Garg, A.; Bloom, G.; Walker, D.G.; Brieger, W.R.; Rahman, M.H. Poverty and Access to Health Care in Developing Countries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1136, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, N.C.; Meriwether, W.E.; Caringi, J.; Newcomer, S.R. Barriers to Healthcare Access among U.S. Adults with Mental Health Challenges: A Population-Based Study. SSM-Popul. Health 2021, 15, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women Pakistan. National Report on the Status of Women in Pakistan, 2023: A Summary; UN Women: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2023; Available online: https://pakistan.unwomen.org (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Khan, S.J.; Asif, M.; Aslam, S.; Khan, W.J.; Hamza, S.A. Pakistan’s Healthcare System: A Review of Major Challenges and the First Comprehensive Universal Health Coverage Initiative. Cureus 2023, 15, e44641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan’s Population Explosion—A Blessing or a Curse?—Pakistan—DAWN.COM. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1844614 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Khan, S.A. Situation Analysis of Health Care System of Pakistan: Post 18 Amendments. Health Care Curr. Rev. 2019, 7, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, K.; Hussain, M.; Afzal, M.; Gilani, S.A. Factors Affecting Health Seeking Behavior and Health Services in Pakistan. Natl. J. Health Sci. 2020, 5, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurji, Z.; Premani, Z.S.; Mithani, Y. Analysis of The Health Care System of Pakistan: Lessons Learnt and Way Forward. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2016, 28, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- “Over 50m Pakistanis Lack Access to Essential Healthcare”—Newspaper—DAWN.COM. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1878178 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Habib, S.S.; Jamal, W.Z.; Zaidi, S.M.A.; Siddiqui, J.U.R.; Khan, H.M.; Creswell, J.; Batra, S.; Versfeld, A. Barriers to Access of Healthcare Services for Rural Women—Applying Gender Lens on Tb in a Rural District of Sindh, Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamneh, T.S.; Teshale, A.B.; Yeshaw, Y.; Alem, A.Z.; Ayalew, H.G.; Liyew, A.M.; Tessema, Z.T.; Tesema, G.A.; Worku, M.G. Socioeconomic Inequality in Barriers for Accessing Health Care among Married Reproductive Aged Women in Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Decomposition Analysis. BMC Womens. Health 2022, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, H.K.; Endale, H.T.; Aragie, H.; Tesfaye, W.; Getnet, M.; Asefa, T.; Gela, Y.Y.; Zegeye, A.F. Barriers to Healthcare Access among Female Youths in Mozambique: A Mixed-Effects and Spatial Analysis Using DHS 2022/23 Data. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesema, G.A.; Tessema, Z.T.; Tamirat, K.S. Decomposition and Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Health Care Access Challenges among Reproductive Age Women in Ethiopia, 2005–2016. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, A.A.; Darteh, E.K.M.; Agbaglo, E.; Dadzie, L.K.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Tetteh, J.K.; Baatiema, L.; Yaya, S. Barriers to Accessing Healthcare among Women in Ghana: A Multilevel Modelling. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, B.; El-Khatib, Z.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Seidu, A.A.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Keetile, M.; Yaya, S. Breaking Barriers to Healthcare Access: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual- and Community-Level Factors Affecting Women’s Access to Healthcare Services in Benin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, N.L.; Brown, C.; Nu’usolia, O.; Ah-Ching, J.; Muasau-Howard, B.; McGarvey, S.T. Barriers to Adequate Prenatal Care Utilization in American Samoa. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 2284–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragie, H.; Negash, H.K.; Getnet, M.; Tesfaye, W.; Gela, Y.Y.; Asefa, T.; Woldeyes, M.M.; Endale, H.T. Barriers to Healthcare Access: A Multilevel Analysis of Individual- and Community-Level Factors Affecting Female Youths’ Access to Healthcare Services in Senegal. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, A.A.; Agbaglo, E.; Dadzie, L.K.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Tetteh, J.K. Individual and Contextual Factors Associated with Barriers to Accessing Healthcare among Women in Papua New Guinea: Insights from a Nationwide Demographic and Health Survey. Int. Health 2021, 13, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, A.A. Mixed Effects Analysis of Factors Associated with Barriers to Accessing Healthcare among Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: Insights from Demographic and Health Surveys. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.; Ashkar, S.; Alkaiyat, A.; Bacchus, L.; Colombini, M.; Feder, G.; Evans, M. Barriers to Women’s Disclosure of Domestic Violence in Health Services in Palestine: Qualitative Interview-Based Study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, T.; Agampodi, T.; Evans, M.; Knipe, D.; Rathnayake, A.; Rajapakse, T. Barriers to Help-Seeking from Healthcare Professionals amongst Women Who Experience Domestic Violence—A Qualitative Study in Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamirat, K.S.; Tessema, Z.T.; Kebede, F.B. Factors Associated with the Perceived Barriers of Health Care Access among Reproductive-Age Women in Ethiopia: A Secondary Data Analysis of 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsegaw, M.; Mulat, B.; Shitu, K. Problems with Accessing Healthcare and Associated Factors among Reproductive-Aged Women in the Gambia Using Gambia Demographic and Health Survey 2019/2020: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e073491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahinkorah, B.O.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Seidu, A.-A.; Odusina, E.K.; Keetile, M.; Yaya, S. Examining Barriers to Healthcare Access and Utilization of Antenatal Care Services: Evidence from Demographic Health Surveys in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, C.J.; Darling, E.K. Barriers and Facilitators of Accessing Perinatal Mental Health Services: The Perspectives of Women Receiving Continuity of Care Midwifery. Midwifery 2018, 65, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakang’o, S.B.; Booth, A. Women’s Perceived Barriers to Giving Birth in Health Facilities in Rural Kenya: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Midwifery 2018, 67, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bintabara, D.; Nakamura, K.; Seino, K. Improving Access to Healthcare for Women in Tanzania by Addressing Socioeconomic Determinants and Health Insurance: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Population by Country 2023 (Live). Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/ (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Adeleye, O.; Adebowale, A.; Adeyemo, O.; Adeoye, I.; Afolabi, R.; Fagbamigbe, A.; Palamuleni, M. Decomposition and Spatiotemporal Analysis of Barriers to Healthcare Access among Women of Childbearing Age in Nigeria, Using Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey from 2003 to 2018. J. Afr. Popul. Stud. 2023, 36, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.N.; Kumar, V.; Prasad, R.; Punia, M. Geographically Weighted Method Integrated with Logistic Regression for Analyzing Spatially Varying Accuracy Measures of Remote Sensing Image Classification. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2021, 49, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsdon, C.; Fotheringham, A.S.; Charlton, M.E. Geographically Weighted Regression: A Method for Exploring Spatial Nonstationarity. Geogr. Anal. 1996, 28, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’SULLIVAN, D. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships, by A. S. Fotheringham, C. Brunsdon, and M. Charlton. Geogr. Anal. 2003, 35, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Population Studies—NIPS/Pakistan; ICF. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18; NIPS/Pakistan and ICF: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2019.

- Spatial Data Repository—Welcome. Available online: https://spatialdata.dhsprogram.com/home/ (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Htun, N.M.M.; Hnin, Z.L.; Khaing, W. Empowerment and Health Care Access Barriers among Currently Married Women in Myanmar. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The DHS Program—GPS Data. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/Methodology/GPS-Data.cfm (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Anselin, L. Local Indicators of Spatial Association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valck, J.; Broekx, S.; Liekens, I.; De Nocker, L.; Van Orshoven, J.; Vranken, L. Contrasting Collective Preferences for Outdoor Recreation and Substitutability of Nature Areas Using Hot Spot Mapping. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 151, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goovaerts, P. Geostatistical Approaches for Incorporating Elevation into the Spatial Interpolation of Rainfall. J. Hydrol. 2000, 228, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Srinivasan, R. GIS-Based Spatial Precipitation Estimation: A Comparison of Geostatistical Approaches1. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2009, 45, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kamble, T.; Machiwal, D. Comparison of Ordinary and Bayesian Kriging Techniques in Depicting Rainfall Variability in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions of North-West India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolarinwa, O.A.; Tessema, Z.T.; Frimpong, J.B.; Babalola, T.O.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.A. Spatial Distribution and Factors Associated with Adolescent Pregnancy in Nigeria: A Multi-Level Analysis. Arch. Public Health 2022, 80, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshale, A.B.; Alem, A.Z.; Yeshaw, Y.; Kebede, S.A.; Liyew, A.M.; Tesema, G.A.; Agegnehu, C.D. Exploring Spatial Variations and Factors Associated with Skilled Birth Attendant Delivery in Ethiopia: Geographically Weighted Regression and Multilevel Analysis. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Propastin, P.; Kappas, M.; Erasmi, S. Application of Geographically Weighted Regression to Investigate the Impact of Scale on Prediction Uncertainty by Modelling Relationship between Vegetation and Climate. Int. J. Spat. Data Infrastruct. Res. 2008, 3, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tebeje, T.M.; Abebe, M.; Aragaw, F.M.; Seifu, B.L.; Mare, K.U.; Shewarega, E.S.; Sisay, G.; Seboka, B.T. A Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression Analysis of Teenage Pregnancy and Associated Factors among Adolescents Aged 15 to 19 in Ethiopia Using the 2019 Mini-Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekol, Y.M.; Jemberie, S.B.; Goshe, B.T.; Tesema, G.A.; Tessema, Z.T.; Gebrehewet, L.G. Geographic Weighted Regression Analysis of Hot Spots of Modern Contraceptive Utilization and Its Associated Factors in Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakistan Overview: Development News, Research, Data|World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/pakistan/overview (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Minyihun, A.; Tessema, Z.T. Determinants of Access to Health Care among Women in East African Countries: A Multilevel Analysis of Recent Demographic and Health Surveys from 2008 to 2017. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, A.F. Healthcare Challenges in Gilgit Baltistan: The Way Forward. Pakistan J. Public Health 1970, 7, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqui, M.A.; Ali, K.N.; Riaz, S. Utilisation and Barriers of Social Health Protection Program among Its Enrolled Population of Federally Administrative Areas, Pakistan. BMJ Open Qual. 2024, 13, e002375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi Jafree, S.; Barlow, J. Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Key Barriers and Facilitators to the Delivery and Uptake of Primary Healthcare Services to Women in Pakistan. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e076883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafree, S.R.; Mahmood, Q.K.; Momina, A.U.; Fischer, F.; Barlow, J. Protocol for a Systematic Review of Barriers, Facilitators and Outcomes in Primary Healthcare Services for Women in Pakistan. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midhet, F.; Hanif, M.; Khalid, S.N.; Khan, R.S.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, S.A. Factors Associated with Maternal Health Services Utilization in Pakistan: Evidence from Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey, 2019. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervin, J.; Venkateswaran, M.; Nu, U.T.; Rahman, M.; O’Donnell, B.F.; Friberg, I.K.; Rahman, A.; Frøen, J.F. Determinants of Utilization of Antenatal and Delivery Care at the Community Level in Rural Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuamah, G.B.; Agyei-Baffour, P.; Mensah, K.A.; Boateng, D.; Quansah, D.Y.; Dobin, D.; Addai-Donkor, K. Access and Utilization of Maternal Healthcare in a Rural District in the Forest Belt of Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamirat, K.; Tessema, Z.; Bikale, F. Correlates of Health Care Access Problems among Reproductive Age Women in Ethiopia: In-Depth Analysis of 2016 Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey. Res. Sq. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, S.; Zegeye, B.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Seidu, A.-A.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Adjei, N.K.; Shibre, G. Predictors of Skilled Birth Attendance among Married Women in Cameroon: Further Analysis of 2018 Cameroon Demographic and Health Survey. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Imani, A.; Golestani, M.; Ajmera, P.; Majeed, J.; Carlerby, H.; Dalal, K. Barriers to Access Health Facilities: A Self-Reported Cross- Sectional Study of Women in India. Health Open Res. 2024, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, K.K.; Nilima, S.; Zahura, F.T.; Bari, W. Do Education and Living Standard Matter in Breaking Barriers to Healthcare Access among Women in Bangladesh? BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinata, H.; Lwin, K.S.; Eguchi, A.; Ghaznavi, C.; Hashizume, M.; Nomura, S. Factors Associated with Barriers to Healthcare Access among Ever-Married Women of Reproductive Age in Bangladesh: Analysis from the 2017–2018 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0289324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif Naveed, G.W.; Ghaus, M.U. Geography of Poverty in Pakistan: Explaining Regional Inequality; No. April; Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2017.

- Misu, F.; Alam, K. Comparison of Inequality in Utilization of Maternal Healthcare Services between Bangladesh and Pakistan: Evidence from the Demographic Health Survey 2017–2018. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Rajak, B.; Dehury, R.K.; Mathur, S.; Samal, A. Differential Access of Healthcare Services and Its Impact on Women in India: A Systematic Literature Review. SN Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentie, E.A.; Asmamaw, D.B.; Negash, W.D.; Belachew, T.B.; Baykeda, T.A.; Addis, B.; Tamir, T.T.; Wubante, S.M.; Endawkie, A.; Zegeye, A.F.; et al. Spatial Distribution and Determinants of Barriers of Health Care Access among Female Youths in Ethiopia, a Mixed Effect and Spatial Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbamigbe, A.F.; Idemudia, E.S. Barriers to Antenatal Care Use in Nigeria: Evidences from Non-Users and Implications for Maternal Health Programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, Y.B.; Aurangzeb, B.; Dibley, M.J.; Alam, A. Qualitative Exploration of Facilitating Factors and Barriers to Use of Antenatal Care Services by Pregnant Women in Urban and Rural Settings in Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, H.S.H.; Chohan, F.A.; Murtaza, M.; Qamar, I.; Zahra, F.T.; Shahab, A.; Khalid, Z.; Ismail, W. How Illiteracy Affects the Health of Women and Their Children in PMC Colony F Block. Apmc 2017, 11, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, C. The Contribution of Education to Economic Growth; K4D Helpdesk Report; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2017; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek, E.A.; Woessmann, L. Do Better Schools Lead to More Growth? Cognitive Skills, Economic Outcomes, and Causation. J. Econ. Growth 2012, 17, 267–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.P.S.C.; Nunes, B.P.; Duro, S.M.S.; Facchini, L.A. Socioeconomic Determinants of Access to Health Services among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Rev. Saude Publica 2017, 51, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, Z.; Simbar, M.; Dolatian, M.; Zayeri, F. Correlation between Social Determinants of Health and Women’s Empowerment in Reproductive Decision-Making among Iranian Women. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.; McGuire, A. The Determinants of Access to Health Care and Medicines in India. Appl. Econ. 2016, 48, 1618–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Sinha, R.; Priya, A.; Rahman, M.H.U. Barriers to Healthcare Utilization among Married Women in Afghanistan: The Role of Asset Ownership and Women’s Autonomy. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.S.; Ali, S.S.; Nadeem, S.; Memon, Z.; Soofi, S.; Madhani, F.; Karim, Y.; Mohammad, S.; Bhutta, Z.A. Perpetuation of Gender Discrimination in Pakistani Society: Results from a Scoping Review and Qualitative Study Conducted in Three Provinces of Pakistan. BMC Womens. Health 2022, 22, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Shah, G.; Amir-ud-Din, R. Consanguineous Marriages and Domestic Violence against Women: Evidence from Pakistan. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakar, R.; Zakar, M.Z.; Abbas, S. Domestic Violence Against Rural Women in Pakistan: An Issue of Health and Human Rights. J. Fam. Violence 2016, 31, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenhofer, S.; Seibold, C. Emergency Healthcare Experiences of Women Living with Intimate Partner Violence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 2253–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulesci, S.; Leone, M.; Zafar, S. Domestic Violence Laws and Social Norms: Evidence from Pakistan; No. 0324; Department of Economics, Trinity College Dublin: Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, F.; Pals, H. Attitudes Toward Wife Beating in Pakistan: Over-Time Comparative Trends by Gender. Violence Against Women 2024, 31, 398–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Ali, T.; Khuwaja, A. Domestic Violence among Pakistani Women: An Insight into Literature. Isra Med. J. 2009, 1, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Papas, L.; Hollingdrake, O.; Currie, J. Social Determinant Factors and Access to Health Care for Women Experiencing Domestic and Family Violence: Qualitative Synthesis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichter, M.E.; Ogden, S.N.; Tuepker, A.; Iverson, K.M.; True, G. Survivors’ Input on Health Care-Connected Services for Intimate Partner Violence. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 1744–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Thomas, K.A.; Sorenson, S.B. “I Didn’t Know I Could Turn Colors”: Health Problems and Health Care Experiences of Women Strangled by an Intimate Partner. Soc. Work Health Care 2012, 51, 798–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, B. Domestic Violence in Barriers to Health Care for HIV-Positive Women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006, 20, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.S.; Silberberg, M.R.; Brown, A.J.; Yaggy, S.D. Health Needs and Barriers to Healthcare of Women Who Have Experienced Intimate Partner Violence. J. Women’s Health 2007, 16, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Women Characteristics | N (=8127) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-Level | ||

| Age | ||

| 15–19 | 284 | 3.49 |

| 20–34 | 6028 | 74.17 |

| 35–49 | 1815 | 22.34 |

| Women’s Educational Status | ||

| No education | 3763 | 46.30 |

| Primary | 1296 | 15.95 |

| Secondary | 1905 | 23.45 |

| Higher | 1163 | 14.31 |

| 4+ ANC Visits | ||

| Inadequate ANC visits | 4085 | 50.26 |

| Adequate ANC visits | 4042 | 49.74 |

| Place of Delivery | ||

| Home | 2582 | 31.76 |

| Health facility | 5546 | 68.24 |

| Media Exposure | ||

| No | 2975 | 36.61 |

| Yes | 5152 | 63.39 |

| Currently Working Status | ||

| No | 7050 | 86.75 |

| Yes | 1077 | 13.25 |

| Visited a Health facility in the Last 12 Months | ||

| No | 1566 | 19.27 |

| Yes | 6561 | 80.73 |

| Health Insurance (HI) Coverage | ||

| No HI | 8000 | 98.44 |

| Yes HI | 127 | 1.56 |

| Terminated Pregnancy (TP) | ||

| No TP | 5525 | 67.98 |

| Yes TP | 2602 | 32.02 |

| Attitude Towards Domestic Violence | ||

| Did not accept violence | 4459 | 54.87 |

| Accepted violence | 3668 | 45.13 |

| Relationship/Household-Level | ||

| Gender of Household Head | ||

| Male | 7203 | 88.62 |

| Female | 924 | 11.38 |

| No. of Living Children | ||

| No children | 88 | 1.08 |

| 1–2 children | 3513 | 43.22 |

| 3–4 children | 2662 | 32.75 |

| 5 or more children | 1864 | 22.94 |

| Husband’s Working Status | ||

| Not working | 251 | 3.09 |

| Working | 7876 | 96.91 |

| Wealth Index | ||

| Poorest | 1801 | 22.17 |

| Poorer | 1789 | 22.02 |

| Middle | 1695 | 20.86 |

| Richer | 1482 | 18.23 |

| Richest | 1359 | 16.72 |

| Husband’s Educational Status | ||

| No education | 2148 | 26.43 |

| Primary | 1277 | 15.72 |

| Secondary | 3033 | 37.32 |

| Higher | 1669 | 20.54 |

| Women’s Assets of Ownership | ||

| Does not own house/land | 7887 | 97.05 |

| Own house/land | 240 | 2.95 |

| Decision-Making Power of Women | ||

| Women not involved | 5471 | 67.32 |

| Women involved | 2656 | 32.68 |

| Community-Level Factors | ||

| Region | ||

| Punjab | 3359 | 41.33 |

| Sindh | 1550 | 19.07 |

| KPK | 1088 | 13.39 |

| Balochistan | 370 | 4.55 |

| GB | 660 | 8.12 |

| ICT | 52 | 0.64 |

| AJK | 894 | 11.01 |

| FATA | 154 | 1.90 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 2429 | 29.89 |

| Rural | 5698 | 70.11 |

| Variables | Coefficients | p-Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.32 | 0.070 | ------- |

| Women who have 5+ living children | 0.24 | 0.000 * | 3.45 |

| Inadequate ANC visits | 0.31 | 0.000 * | 6.09 |

| Poorer (wealth index) | 0.09 | 0.020 * | 2.19 |

| Respondent did not take part in decision-making | 0.55 | 0.000 * | 2.06 |

| Respondent’s primary education | 0.443 | 0.000 * | 4.84 |

| Respondent accepted domestic violence | 0.17 | 0.000 * | 3.96 |

| Diagnostic Measures | Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| AICc | 2881.82 | ------ |

| R square | 0.93 | ------ |

| Adjusted R square | 0.93 | ------ |

| Koenker (BP) Statistics | 109.56 | 0.000 * |

| Jarque–Bera Statistics | 902.22 | 0.000 * |

| Diagnostic Measures | Value |

|---|---|

| AICc | 2735.18 |

| R square | 0.96 |

| Adjusted R square | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamal, A.; Shah, G.H.; Hafeez, A.; Siddiqa, M.; Owens, C. Mapping Geographic Disparities in Healthcare Access Barriers Among Married Women in Pakistan: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2448. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192448

Kamal A, Shah GH, Hafeez A, Siddiqa M, Owens C. Mapping Geographic Disparities in Healthcare Access Barriers Among Married Women in Pakistan: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2448. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192448

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamal, Asifa, Gulzar H. Shah, Afrah Hafeez, Maryam Siddiqa, and Charles Owens. 2025. "Mapping Geographic Disparities in Healthcare Access Barriers Among Married Women in Pakistan: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2448. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192448

APA StyleKamal, A., Shah, G. H., Hafeez, A., Siddiqa, M., & Owens, C. (2025). Mapping Geographic Disparities in Healthcare Access Barriers Among Married Women in Pakistan: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey. Healthcare, 13(19), 2448. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192448