Sexual Satisfaction and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Saudi Survivors of Cervical and Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- The Quality of Sexual Life Questionnaire for breast cancer survivors in Mainland China provided items on orgasmic intensity, partner satisfaction, and sexual normalcy, ensuring cross-domain comparability [4].

- Sexual Function and Satisfaction (8 items);

- Psychological and Emotional Well-Being (3 items);

- Social and Relationship Quality (3 items);

- Importance of Each Domain (14 items rated separately).

2.1. Translation, Content Validation, and Reliability

2.2. Variables and Measurement

- Primary outcomes were total scores in each of the three domains (sexual function, psychological well-being, and social relationships);

- Independent variables included age, marital status, education level, employment status, cancer type (breast or cervical), age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, and treatment received.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Population

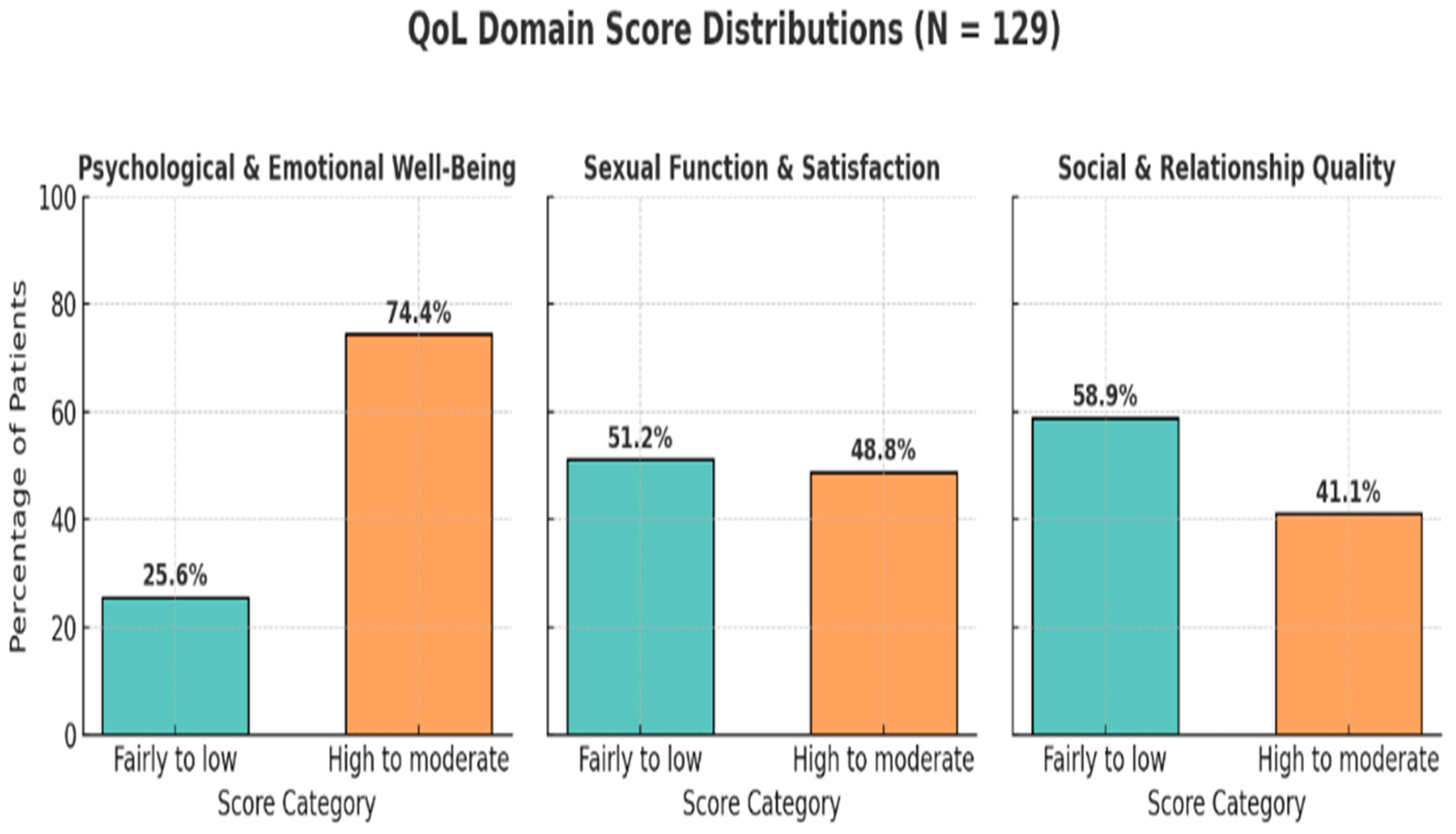

3.2. Perceived Quality of Sexual Life Across the Three Domains

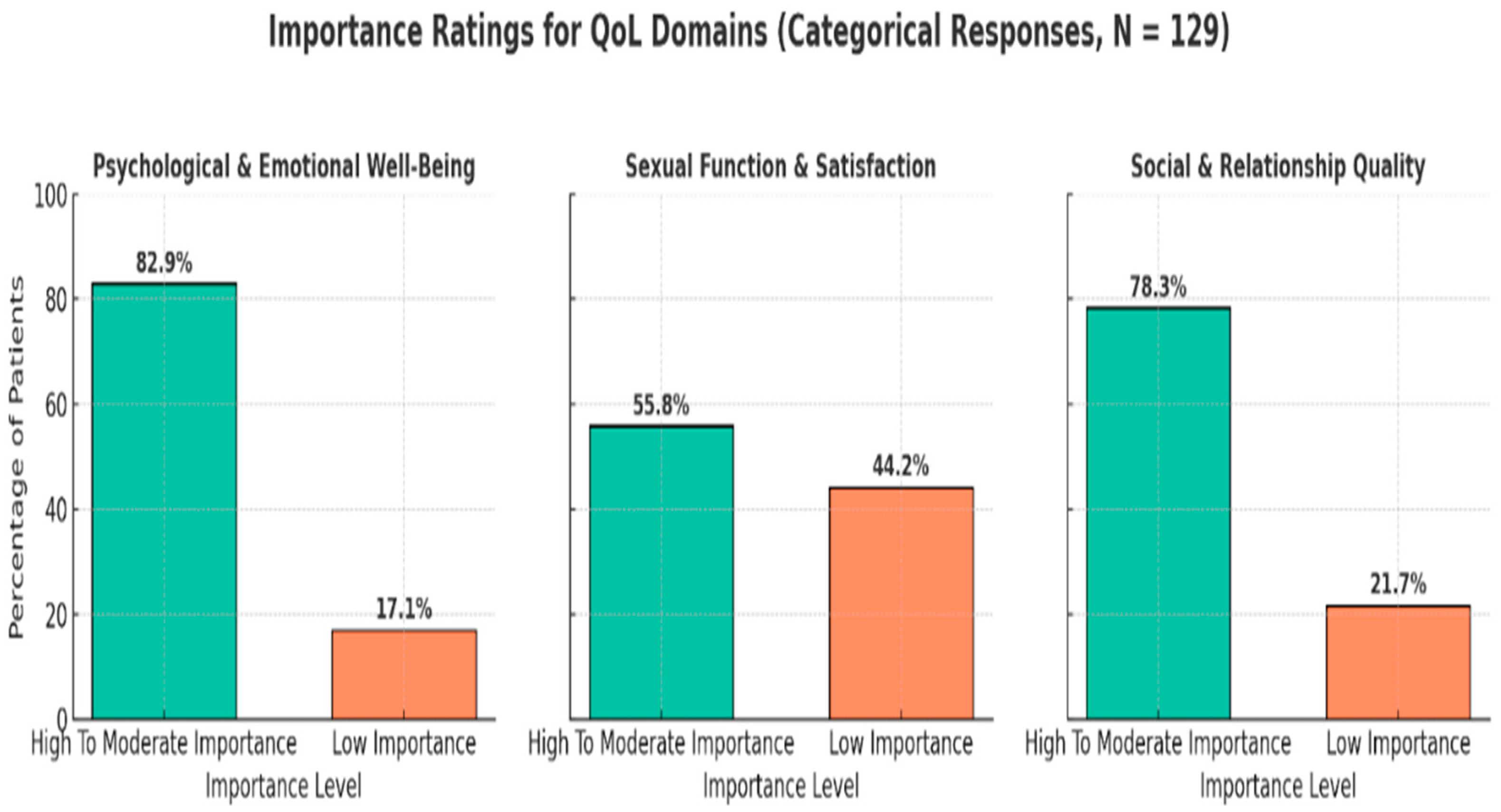

3.3. Perceived Importance of QoL Domains

3.4. Bivariate Analysis for the Three Domains Across Sociodemographic Variables

3.5. Predictors of Sexual Quality of Life (Multivariate Analysis)

3.6. Psychological and Emotional Well-Being

3.7. Sexual Function and Satisfaction

3.8. Social and Relationship Quality

4. Discussion

4.1. Predictors Across Domains

4.2. Psychological and Emotional Well-Being

4.3. Sexual Function and Satisfaction

4.4. Social and Relationship Quality

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Basudan, A.M. Breast cancer incidence patterns in the Saudi female population: A 17-year retrospective analysis. Medicina 2022, 58, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Cervical Cancer Country Profile: Saudi Arabia. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cervical-cancer-sau-country-profile-2021 (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Vegunta, S.; Kuhle, C.L.; Vencill, J.A.; Lucas, P.H.; Mussallem, D.M. Sexual health after a breast cancer diagnosis: Addressing a forgotten aspect of survivorship. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, L.W.; Zhang, C.; Jin, F.; Wang, A.P. Development of a quality of sexual life questionnaire for breast cancer survivors in Mainland China. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 4101–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Mardani, A.; Ghafourifard, M.; Vaismoradi, M. Qualitative exploration of sexual life among breast cancer survivors at reproductive age. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, C.; Singh, M.; Tock, W.L.; Eyrenci, A.; Galica, J.; Hébert, M.; Estapé, T. Fear of cancer recurrence, health anxiety, worry, and uncertainty: A scoping review about their conceptualization and measurement within breast cancer survivorship research. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alattar, N.; Felton, A.; Stickley, T. Mental health and stigma in Saudi Arabia: A scoping review. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2021, 26, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alissa, N.A. Social barriers as a challenge in seeking mental health among Saudi Arabians. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.N. Psychosocial Challenges in Adolescents and Young Adults Affected by Cancer: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfiq, W.A.; Ogle, J.P. Constructing identity against a backdrop of cultural change: Experiences of freedom and constraint in public dress among Saudi women. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2024, 42, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chargari, C.; Arbyn, M.; Leary, A.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Basu, P.; Bray, F.; Morice, P. Increasing global accessibility to high-level treatments for cervical cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 164, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalawi, E.; Allemani, C.; Al-Zahrani, A.S.; Coleman, M.P. Cervical cancer in Saudi Arabia: Trends in survival by stage at diagnosis and geographic region. Ann. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljadani, F.F.; Nughays, R.O.; Alharbi, G.E.; Almazroy, E.A.; Elyas, S.K.; Danish, H.E.; Mikwar, Z. Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Patients in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2025, 17, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiehn, E.; Ricci, C.; Alvarez-Perea, A.; Perkin, M.R.; Jones, C.J.; Akdis, C. Adherence to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist in articles published in EAACI Journals: A bibliographic study. Allergy 2021, 76, 3581–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahmoud, A.; Russell, R.; Kelley, E.; Fraiman, E.; Goldblatt, C.; Loria, M.; Pope, R. Sexual satisfaction and function (SatisFunction) survey post-vaginoplasty for transgender and gender diverse individuals: Preliminary development and content validity for future clinical use. Sex. Med. 2025, 13, qfaf011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberguggenberger, A.; Martini, C.; Huber, N.; Fallowfield, L.; Hubalek, M.; Daniaux, M.; Meraner, V. Self-reported sexual health: Breast cancer survivors compared to women from the general population–an observational study. BMC cancer 2017, 17, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, B.; Barclay, S.; Kuhn, I.; Eagar, K.; Bausewein, C.; Murtagh, F.; Shokraneh, F. Implementing patient-centred outcome measures in palliative care clinical practice for adults (IMPCOM): Protocol for an update systematic review of facilitators and barriers. F1000Research 2023, 12, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younan, L.S.; Clinton, M.E.; Fares, S.A.; Samaha, H. The translation and cultural adaptation validity of the Actual Scope of Practice Questionnaire. East Mediterr. Health J. 2019, 25, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.; Elmer, M.; Ludlam, S.; Shay, K.; Bentley, S.; Trennery, C.; Gater, A. Evaluation of the content validity and cross-cultural validity of the study participant feedback questionnaire (SPFQ). Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2020, 54, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, C.G. Cronbach’s alpha. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1505–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Yenipınar, A.; Koç, Ş.; Çanga, D.; Kaya, F. Determining sample size in logistic regression with G-Power. Black Sea J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 2, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze, G.; Schemper, M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalczyk, R.; Nowosielski, K.; Cedrych, I.; Krzystanek, M.; Glogowska, I.; Streb, J.; Lew-Starowicz, Z. Factors affecting sexual function and body image of early-stage breast cancer survivors in Poland: A short-term observation. Clin. Breast Cancer 2019, 19, e30–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Wang, L.; Xing, J.; Shan, X.; Wu, J.; Liu, X. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women with cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubion, S.S.; Kingsberg, S.A. Understanding the unmet sexual health needs of women with breast cancer. Menopause 2019, 26, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konieczny, M.; Cipora, E.; Sygit, K.; Fal, A. Quality of life of women with breast cancer and socio-demographic factors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosir, U.; Wiedemann, M.; Wild, J.; Bowes, L. Psychiatric disorders in adolescent cancer survivors: A systematic review of prevalence and predictors. Cancer Rep. 2019, 2, e1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dawish, A.; Wahass, S. Stigma in Mental Health: Perceptions and Attitudes of Saudi People towards Mental Illness. EC Neurol. 2020, 12, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Asuquo, E.F.; Akpan-Idiok, P.A. The Exceptional Role of Women as Primary Caregivers for People. In Suggestions for Addressing Clinical and Non-Clinical Issues in Palliative Care; Intech Open: London, UK, 2021; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Mollica, M.A.; Mayer, D.K.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Kim, Y.; Buckenmaier, S.S.; Sivaram, S.; Jacobsen, P.B. Follow-up care for breast and colorectal cancer across the globe: Survey findings from 27 countries. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2020, 6, 1394–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörfler, C.; Grosse-Rüschkamp, M.S.; Tissen-Diabaté, T.; Krothaler, S.; Beier, K.M.; Hatzler, L. (118) Orgasm and Herat Rate Variability in Female Breast Cancer Survivors: Result From A Psychophysiology Study. J. Sex. Med. 2024, 21 (Suppl. S5), qdae054.112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albugami, N. The Experience of Female Caregivers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | N (%) 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 21 to 30 Years | 43 (33.33) |

| 31 to 45 Years | 59 (45.74) | |

| More than 45 Years | 21 (20.93) | |

| Marital Status | Married | 107 (82.95) |

| Non-Married | 22 (11.05) | |

| Educational Level | Bachelor | 62 (48.06) |

| Graduate studies | 13 (10.08) | |

| Secondary or Less | 54 (41.86) | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 116 (89.92) |

| Non-Saudi | 13 (10.08) | |

| Occupational Status | Employed | 56 (43.41) |

| Non-employed or retired | 73 (56.59) | |

| Number of children | From 1 to 3 | 59 (45.74) |

| From 4 to 10 | 50 (38.76) | |

| None | 20 (15.5) | |

| Age at your first diagnosis | From 21 to 30 Years | 60 (46.51) |

| From 31 to 45 Years | 48 (37.21) | |

| More than 45 Years | 21 (16.28) | |

| When were you diagnosed with cervical or breast cancer? | From 1 to 3 years | 79 (61.24) |

| More than 3 years | 26 (20.16) | |

| Less than a year | 23 (17.83) | |

| Type of diagnosed cancer | ||

| Breast cancer | 63 (48.84) | |

| Cervical cancer | 66 (51.16) | |

| Sexuality score | ||

| Psychological and Emotional Well-Being | Fair-to-low | 33 (25.58) |

| Hig-to-moderate | 96 (74.42) | |

| Sexual Function and Satisfaction | Fair-to-low | 66 (51.16) |

| High-to-moderate | 63 (48.84) | |

| Social and Relationship Qualities | Fair-to-low | 76 (58.91) |

| High-to-moderate | 53 (41.09) | |

| Variable | Psychological and Emotional Well-Being | Sexual Function and Satisfaction | Social and Relationship Qualities | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR 1 | 95% CI 2 | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Age: From 21 to 30 Years vs. More than 45 Years | 0.1 | (0.01, 0.58) | 0.01 | 1.74 | (0.46, 6.61) | 0.41 | 6.28 | (1.37, 28.72) | 0.01 |

| Age: From 31 to 45 Years vs. More than 45 Years | 0.85 | (0.17, 4.07) | n.s | 1.31 | (0.41, 4.25) | 0.64 | 4.59 | (1.17, 17.93) | 0.02 |

| Educational Level: Bachelor vs. Secondary or Less | 0.23 | (0.06, 0.84) | 0.02 | 0.41 | (0.16, 0.98) | 0.04 | 0.91 | (0.36, 2.26) | n.s |

| Educational Level: Graduate studies vs. Secondary or Less | 0.28 | (0.03, 2.06) | n.s | 0.63 | (0.14, 2.8) | 0.54 | 1.76 | (0.36, 8.61) | n.s |

| Have you been treated/ am now/under treatment vs. Yes | 0.77 | (0.23, 2.48) | n.s | 2.48 | (1.11, 5.56) | 0.02 | 1.72 | (0.76, 3.92) | n.s |

| Marital Status: Married vs. Unmarried | 0.51 | (0.09, 2.88) | n.s | 0.81 | (0.28, 2.32) | 0.69 | 0.49 | (0.16, 1.51) | n.s |

| Number of children: From 1 to 3 vs. None | 0.513 | (0.08, 3.15) | n.s | 3.45 | (0.93, 12.75) | 0.06 | 2.92 | (0.86, 9.86) | n.s |

| Number of children: From 4 to 10 vs. None | 0.038 | (0.004, 0.35) | 0.00 | 6.34 | (1.33, 30.24) | 0.02 | 18.5 | (3.42, 100.85) | 0.00 |

| Occupational Status: Employed vs. Unemployed | 0.959 | (0.29, 3.17) | n.s | 1.47 | (0.61, 3.53) | 0.38 | 1.43 | (0.58, 3.51) | n.s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almutairi, W.M. Sexual Satisfaction and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Saudi Survivors of Cervical and Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192443

Almutairi WM. Sexual Satisfaction and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Saudi Survivors of Cervical and Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192443

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmutairi, Wedad M. 2025. "Sexual Satisfaction and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Saudi Survivors of Cervical and Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192443

APA StyleAlmutairi, W. M. (2025). Sexual Satisfaction and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Saudi Survivors of Cervical and Breast Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Healthcare, 13(19), 2443. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192443