The Off-Label Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Sexual Behavior Management: Risks and Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Reference Search Strategy

2.2. Study Eligibility

2.3. Reference Bias Assessment

3. Results

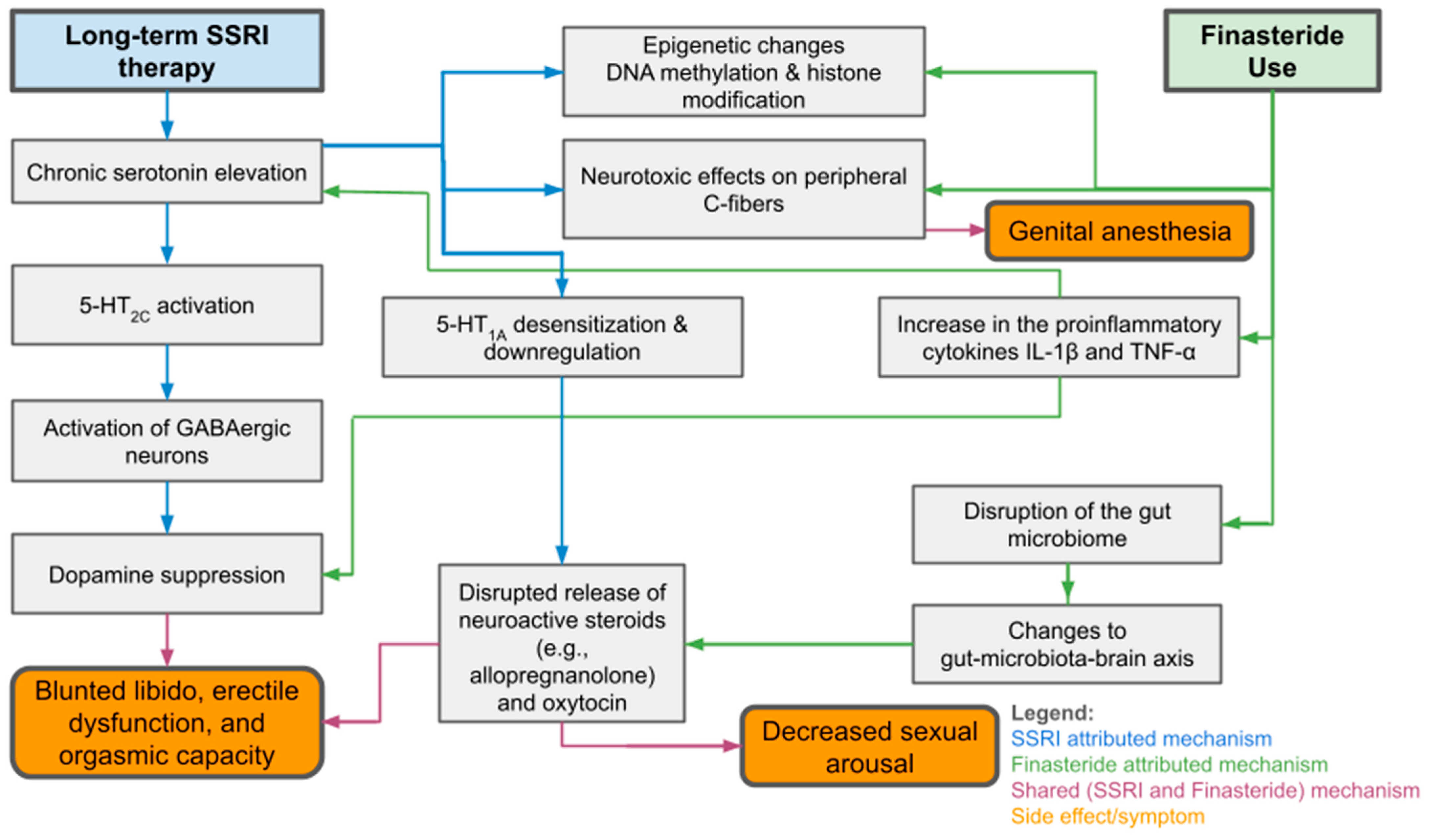

3.1. Proposed Mechanisms

3.2. Post SSRI Sexual Dysfunction and Similar Disorders

3.3. Hypersexuality Associated with SSRI Use

3.4. Comparison to Other Pharmaceutical Options

3.5. Strength of Existing Literature

3.6. Prevalence of Sexual Side Effects and Treatment Options for Them

3.7. Use in Special Populations

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Sexual Safety on Mental Health Wards. 2018. Available online: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20180911c_sexualsafetymh_report.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Tripathi, A.; Agrawal, A.; Joshi, M. Treatment-Emergent Sexual Dysfunctions due to Antidepressants: A Primer on Assessment and Management Strategies. Indian J. Psychiatry 2024, 66, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giorgi, R.; Series, H. Treatment of Inappropriate Sexual Behavior in Dementia. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2016, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Muñoz, F.; D’Ocón, P.; Romero, A.; De Berardis, D.; Álamo, C. Did Serendipity Contribute to the Discovery of New Antidepressant Drugs? Historical Analysis Using Operational Criteria. Alpha Psychiatry 2025, 26, 40037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, A.; Jones, H.; Bangash, F.; Gude, J. Treatment and Management of Sexual Disinhibition in Elderly Patients with Neurocognitive Disorders. Cureus 2021, 13, e18463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Kataoka, Y.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A. National Prescription Patterns of Antidepressants in the Treatment of Adults with Major Depression in the US between 1996 and 2015: A Population Representative Survey Based Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.; Wadhwa, R. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. StatPearls [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554406/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Edinoff, A.N.; Akuly, H.A.; Hanna, T.A.; Ochoa, C.O.; Patti, S.J.; Ghaffar, Y.A.; Kaye, A.D.; Viswanath, O.; Urits, I.; Boyer, A.G.; et al. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Adverse Effects: A Narrative Review. Neurol. Int. 2021, 13, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, I.; Skov, J.; Falhammar, H.; Roos, M.; Lindh, J.D.; Mannheimer, B. The Association of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Venlafaxine with Profound Hyponatremia. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 193, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, M. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor-Induced Sexual Dysfunction: Current Management Perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safak, Y.; Inal Azizoglu, S.; Alptekin, F.B.; Kuru, T.; Karadere, M.E.; Kurt Kaya, S.N.; Yılmaz, S.; Yıldırım, N.N.; Kılıçtutan, A.; Ay, H.; et al. Antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in outpatients. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, Y.; Montejo, A.; Martín, J.; LLorca, G.; Bueno, G.; Blázquez, J. Understanding the Mechanism of Antidepressant-Related Sexual Dysfunction: Inhibition of Tyrosine Hydroxylase in Dopaminergic Neurons after Treatment with Paroxetine but Not with Agomelatine in Male Rats. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Sheetrit, J.; Hermon, Y.; Birkenfeld, S.; Gutman, Y.; Csoka, A.B.; Toren, P. Estimating the risk of irreversible post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD) due to serotonergic antidepressants. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2023, 22, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, D.; Mangin, D. Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction: Barriers to quantifying incidence and prevalence. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2024, 33, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaas, S.; Siva, J.B.; Bak, M.; Govers, M.; Schreiber, R. The pathophysiology of Post SSRI Sexual Dysfunction—Lessons from a case study. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, N.E.; Ahuja, M.; Hatch, S.; Seitz, D.P.; McGowan, J.; Watt, J.A. Treatment of Inappropriate Sexual Behavior in Persons with Dementia: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2025, 73, 2589–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; The Joanna Briggs Institute: North Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2017; Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Case_Reports2017_0.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias Tool for Animal Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A Scale for the Quality Assessment of Narrative Review Articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Health. Quality Asessment Tool for Case Series Studies. Nih.gov. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- National Institute of Health. Quality Asessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Nih.gov. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Tarchi, L.; Merola, G.P.; Baccaredda-Boy, O.; Arganini, F.; Cassioli, E.; Rossi, E.; Maggi, M.; Baldwin, D.S.; Ricca, V.; Castellini, G. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, post-treatment sexual dysfunction and persistent genital arousal disorder: A systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2023, 32, 1053–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, S. A clinical review of antidepressants, their sexual side-effects, post-SSRI sexual dysfunction, and serotonin syndrome. Br. J. Nurs. 2023, 32, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, D. Antidepressants and sexual dysfunction: A history. J. R. Soc. Med. 2020, 113, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, B.; Norman, C.; Hamilton, J.; Cass, S.; Lambert, A.; Tovey, L.; Hocken, K.; Marshall, E.; Lievesley, R.; Hamilton, L.; et al. Evaluation of selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors and anti-androgens to manage sexual compulsivity in individuals serving a custodial sentence for a sexual offence. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2024, 35, 425–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, V.; Masson, M.; Lancon, C.; Boyer, L.; Fond, G. Screening and treatment of Post-Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors sexual dysfunctions. L Encéphale 2022, 48, 599–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patacchini, A.; Cosci, F. A paradigmatic case of postselective serotonin reuptake inhibitors sexual dysfunction or withdrawal after discontinuation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors? J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 40, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalegani, E.; Eissazade, N.; Shalbafan, M.; Salehian, R.; Shariat, S.V.; Askari, S.; Orsolini, L.; Soraya, S. Safety and Efficacy of Drug Holidays for Women with Sexual Dysfunction Induced by Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Other than Fluoxetine: An Open-Label Randomized Clinical Trial. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiss, R.; Malejko, K.; Connemann, B.; Gahr, M.; Durner, V.; Graf, H. Sexual Dysfunction Induced by Antidepressants—A Pharmacovigilance Study Using Data from VigiBaseTM. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waraich, A.; Clemons, C.; Ramirez, R.; Yih, J.; Goldstein, S.; Goldstein, I. MP78-15 Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction (PSSD): Ten year retrospective chart review. J. Urol. 2020, 203 (Suppl. 4), e1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour-Kivi, A.; Eissazade, N.; Shariat, S.V.; Salehian, R.; Soraya, S.; Askari, S.; Shalbafan, M. The effect of drug holidays on sexual dysfunction in men treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) other than fluoxetine: An 8-week open-label randomized clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, T.; Schofield, P.W.; Greenberg, D.; Allnutt, S.H.; Indig, D.; Carr, V.; D’Este, C.; Mitchell, P.B.; Knight, L.; Ellis, A. Reducing Impulsivity in Repeat Violent Offenders: An Open Label Trial of a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, T.; Schofield, P.W.; Knight, L.; Ton, B.; Greenberg, D.; Scott, R.J.; Grant, L.; Keech, A.C.; Gebski, V.; Jones, J.; et al. Sertraline hydrochloride for reducing impulsive behaviour in male, repeat-violent offenders (ReINVEST): Protocol for a phase IV, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savard, J.; Öberg, K.G.; Dhejne, C.; Jokinen, J. A randomised controlled trial of fluoxetine versus naltrexone in compulsive sexual behaviour disorder: Presentation of the study protocol. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e051756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi, S.; Ramanathan, B.; Selvaraj, A.; Sivakumar, P.; Ponnusamy, P. Escitalopram-induced Hypersexuality—Imbalance of the sexual seesaw. J. Psychosexual Health 2025, 7, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatti, S.; Cioffi, L.; Diviccaro, S.; Chrostek, G.; Piazza, R.; Melcangi, R.C. Transcriptomic profile of the male rat hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens after paroxetine treatment and withdrawal: Possible causes of sexual dysfunction. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 62, 4935–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moses, T.E.H.; Javanbakht, A. Resolution of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor–Associated sexual dysfunction after switching from fluvoxamine to fluoxetine. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2023, 43, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Deban, C.E. SSRI-Induced Hypersexuality. Am. J. Psychiatry Resid. J. 2022, 16, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, J.D.A.; Olivier, B. Antidepressants and Sexual Dysfunctions: A Translational Perspective. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2019, 11, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatti, S.; Diviccaro, S.; Cioffi, L.; Falvo, E.; Caruso, D.; Melcangi, R.C. Effects of paroxetine treatment and its withdrawal on neurosteroidogenesis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 132, 105364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, Y. Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction. BMJ 2020, 368, m754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, R.; Bonanno, M.; Manuli, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Cutting the first turf to heal Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction: A male Retrospective cohort study. Medicines 2022, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Rai, A.; Chopra, A.; Dewan, V. Sertraline-Induced hypersexuality in a patient taking bupropion. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012, 14, 26852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mania, I. Citalopram treatment for inappropriate sexual behavior in a cognitively impaired patient. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2006, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Briken, P.; Grubbs, J.; Malandain, L.; Mestre-Bach, G.; Potenza, M.N.; Thibaut, F. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines on the assessment and pharmacological treatment of compulsive sexual behaviour disorder. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 24, 10–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachelek, J.; Zwaans, B.M.M.; Shtein, R.; Peters, K.M. Insights into the peripheral nature of persistent sexual dysfunction associated with post-finasteride, post-SSRI and post-accutane syndromes: Lessons learned from a case study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2025, 57, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatti, S.; Di Domizio, A.; Diviccaro, S.; Cioffi, L.; Marmorini, I.; Falvo, E.; Caruso, D.; Contini, A.; Melcangi, R.C. Identification of a novel off-target of paroxetine: Possible role in sexual dysfunction induced by this SSRI antidepressant drug. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1268, 133690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatti, S.; Diviccaro, S.; Cioffi, L.; Melcangi, R.C. Post-Finasteride syndrome and Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction: Two clinical conditions apparently distant, but very close. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2023, 72, 101114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studt, A.; Gannon, M.; Orzel, J.; Vaughan, A.; Pearlman, A.M. Characterizing post-SSRI sexual dysfunction and its impact on quality of life through an international online survey. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2021, 32, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, D.; Bahrick, A.; Bak, M.; Barbato, A.; Calabrò, R.S.; Chubak, B.M.; Cosci, F.; Csoka, A.B.; D’Avanzo, B.; Diviccaro, S.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for enduring sexual dysfunction after treatment with antidepressants, finasteride and isotretinoin. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 2022, 33, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.E.; Kleinplatz, P.J.; Richardson, H.M.; DiCaita, H.; D’souza, K.; Charest, M.; Rosen, L. Understanding the Experiences of People with Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2025, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro, K.C.; Van Hunsel, F.; Ekhart, C. Persistent sexual dysfunction after SSRI withdrawal: A scoping review and presentation of 86 cases from the Netherlands. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2021, 21, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirani, Y.; Delgado-Ron, J.A.; Marinho, P.; Gupta, A.; Grey, E.; Watt, S.; MacKinnon, K.R.; Salway, T. Frequency of self-reported persistent post-treatment genital hypoesthesia among past antidepressant users: A cross-sectional survey of sexual and gender minority youth in Canada and the US. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 60, 1771–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naguy, A.; Alamiri, B. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor–Related Tardy Sexual Dysfunction. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024, 26, 55684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Franco, D.C.; de Boer, S.F.; Waldinger, M.; Olivier, B.; Olivier, J.D.A. Pharmacological Studies on the Role of 5-HT1A Receptors in Male Sexual Behavior of Wildtype and Serotonin Transporter Knockout Rats. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiolini, A.; Comandini, A.; Dell’Osso, M.C.; Kasper, S. Rediscovering Trazodone for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. CNS Drugs 2012, 26, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, T.K. Antidepressant use during development may impair women’s sexual desire in adulthood. J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannini, T.B.; Lorenzo, G.D.; Bianciardi, E.; Niolu, C.; Toscano, M.; Ciocca, G.; Jannini, E.A.; Siracusano, A. Off-label uses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culos, C.; Di Grazia, M.; Meneguzzo, P. Pharmacological Interventions in Paraphilic Disorders: Systematic review and Insights. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Qu, X.; Hao, H. Progress in the Study of the Effects of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) on the Reproductive System. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1567863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, T.W. Understanding and Managing Compulsive Sexual Behaviors. Psychiatry 2006, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Diviccaro, S.; Melcangi, R.C.; Giatti, S. Post-Finasteride Syndrome: An Emerging Clinical Problem. Neurobiol. Stress 2019, 12, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melcangi, R.C.; Santi, D.; Spezzano, R.; Grimoldi, M.; Tabacchi, T.; Fusco, M.L.; Diviccaro, S.; Giatti, S.; Carrà, G.; Caruso, D.; et al. Neuroactive Steroid Levels and Psychiatric and Andrological Features in Post-Finasteride Patients. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 171, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgren, V.; Malki, K.; Bottai, M.; Arver, S.; Rahm, C. Effect of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonist on Risk of Committing Child Sexual Abuse in Men with Pedophilic Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belknap, S.M.; Aslam, I.; Kiguradze, T.; Temps, W.H.; Yarnold, P.R.; Cashy, J.; Brannigan, R.E.; Micali, G.; Nardone, B.; West, D.P. Adverse Event Reporting in Clinical Trials of Finasteride for Androgenic Alopecia. JAMA Dermatol. 2015, 151, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowska, M.K.; Ortega, R.M.; Wehner, M.R.; Nead, K.T. Association of Second-Generation Antiandrogens with Cognitive and Functional Toxic Effects in Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalçin, N.; Ak, S.; Gürel, Ş.C.; Çeliker, A. Compliance in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 34, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Medication Name | Drug Class | Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Agomelatine | 4.35 (2.07–9.14) | |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Bupropion | 5.83 (5.01–6.8) | |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Citalopram | SSRI | 13.88 (12.19–15.81) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Clomipramine | 4.94 (3.25–7.5) | |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Duloxetine | SNRI | 11.08 (9.9–12.41) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Escitalopram | SSRI | 20.59 (18.32–23.14) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Fluoxetine | SSRI | 7.56 (6.68–8.56) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Fluvoxamine | SSRI | 4.88 (1.65–11.75) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Milnacipran | SNRI | 4.7 (2.44–9.05) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Mirtazapine | Tetracyclic antidepressant | 3.95 (2.98–5.25) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Paroxetine | SSRI | 21.78 (20.1–23.59) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Reboxetine | SNRI | 14.77 (8.89–24.55) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Sertraline | SSRI | 16.94 (15.5–18.5) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Trazodone | Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor | 2.91 (1.99–4.24) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Venlafaxine | SNRI | 8.96 (7.9–10.17) |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Vortioxetine | Serotonin modulation and stimulator | 20.84 (17.31–25.09) |

| Reference | Range of Reported Prevalence of PSSD | Prevalence of PSSD | Study Type |

| Ben-Sheetrit et al., 2023 [13] | - | 0.46% | Retrospective Cohort Study |

| Healy et al., 2024 [14] | - | 26.3% | Review of Animal Study |

| Pirani et al., 2024 [53] | - | 13.2% | Observational Cohort Study |

| Waraich et al., 2020 [30] | - | 4% | Retrospective Cohort Study |

| Overall Literature | 0.46% to 26.3% | - | - |

| Reference | Type | Sample Size | Main Outcomes/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esquivel et al., 2020 [55] | Animal study | Rats | An animal study examining the impact of the serotonin transporter (SERT) gene has on sexual behaviors. Selective pre- and postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptor agonists possess pro-sexual effects in SERT+/+ and SERT−/−, although the response is diminished in SERT−/− animals, most likely due to desensitization of 5-HT1A receptors. |

| Giatti et al., 2021 [40] | Animal study | Rats | SSRI treatment alters neuroactive steroid levels and the expression of key enzymes of steroidogenesis in a brain-tissue and time-dependent manner. The results of the animal study indicate that the effect of paroxetine treatment is directly on neurosteroidogenesis with a negative impact on the expression of steroidogenic enzymes observed on withdrawal of paroxetine treatment. The authors hypothesize that altered neurosteroidogenesis may occur in PSSD. |

| Giatti et al., 2024 [36] | Animal study | Rats | Using RNA, the transcriptomic profile of the hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens of male rats treated daily for 2 weeks with paroxetine (T0) and at 1 month of withdrawal (T1). 7 differentially expressed genes were found at T0 and 1 at T1 in the hypothalamus, 245 at T0 and 6 at T1 in the nucleus accumbens. Genes related to neurotransmitters with a role in sexual behavior and the ward system were found to be dysregulated in the nucleus accumbens, supporting the idea of dysfunction in this brain area. Analysis of differentially expressed genes at T1 in the nucleus accumbens confirmed the persistence of some side effects, providing more information on post-SSRI sexual dysfunction etiopathogenesis. |

| Santana et al., 2019 [12] | Animal study | Rats | Tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity decreased significantly in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area after treatment with paroxetine and labeling was reduced significantly in the zona incerta and mediobasal hypothalamus. The immunoreactive axons in the striatum, cortex, hippocampus, and median eminence almost disappeared in paroxetine-treated rats. Treatment with agomelatine caused a moderate reduction in immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra without appreciable modifications to other regions of the brain. The authors conclude that paroxetine, but not agomelatine, is associated with important decreases in activity in dopaminergic areas of the brain associated with sexual performance impairment in humans after antidepressant treatment. |

| Dewan et al., 2012 [43] | Case Report | 1 male | A 55-year-old male with PTSD and MDD initially treated with bupropion monotherapy which failed to adequately control his symptoms. Sertraline was added and this resulted in improved psychiatric symptoms, but also hypersexuality which gradually resolved one month after stopping sertraline. |

| Klaas et al., 2023 [15] | Case Report | 1 male | A 55-year-old male was started on venlafaxine for depressive symptoms cause by burnout. Over a course of 5 years, the patient attempted to stop treatment twice after his mood improved but developed low libido, delayed ejaculation, erectile dysfunction, “brain zaps”, overactive bladder, and urinary inconsistency each time. After gradually weaning off of venlafaxine gradually over 1.5 months (75 mg to 35.5 mg to 0 mg), the patient was able to stop taking the medication. The patient subsequently experienced sexual dysfunction approximately a year after stopping his venlafaxine, indicating the patient developed PSSD. At the time of writing, the patient had been experiencing symptoms of PSSD but had not received a diagnosis previously. |

| Mahalakshmi et al., 2025 [35] | Case Report | 1 female | A 25-year-old female taking 15 mg of escitalopram per day for depressive symptoms developed intense sexual desire and compulsive masturbation which vanished with discontinuation of the drug |

| Mania et al., 2006 [44] | Case Report | 1 male | A 54-year-old male with bipolar disorder and cognitive deficits secondary to Parkinson disease had been exhibiting intermittent inappropriate sexual behavior for the past 5 years. At one point he was hospitalized, and all of his psychiatric medications were stopped except lithium, this resulted in worsening of his inappropriate sexual behavior. After failing behavioral therapies, the patient was started on 20 mg citalopram and within 2 weeks, his inappropriate sexual behaviors had resolved. |

| Moses et al., 2023 [37] | Case Report | 1 male | A 36-year-old male patient with OCD and anxiety was initially prescribed paroxetine, then sertraline, and then fluvoxamine 250 mg. He also received buspirone 10 mg twice daily. The patient was taking 150 mg fluvoxamine for a year with limited effects on his OCD symptoms but was bothered by adverse effects like fatigue and diminished sex drive. The patient transitioned from fluvoxamine to fluoxetine 40 mg per day and continued on buspirone, 25 days later the patient was no longer complaining about fatigue nor sexual dysfunction. |

| Patacchini et al., 2020 [27] | Case Report | 1 male | A 21-year-old male began treatment with sertraline 100 mg per day for a major depressive episode. During treatment, the patient was irritable, emotionally flat, and felt detached with no perceived benefits from the medication. Psychotherapy helped with his symptoms. After 2 years of treatment with sertraline, the patient was tapered on sertraline. The patient experienced premature ejaculation during the taper and experienced a sense of physical impotence, absence of libido, and genital anesthesia in addition to a recurrence of his mood symptoms. The patient continued to experience these symptoms for 4 years, during which time he was seen by psychiatrists, a specialist of sexual disorders, and an andrologist. Lab tests during this time were normal, but the andrologist noted a non-elicitable bulbocavernosus reflex and hypesthesia/dysesthesia of the genital area. The patient saw some improvement with pramipexole 1 mg per day, but this was continued due to unspecified side effects. The patient also experienced some benefits with bupropion at 300 mg per day for 2 days. Sertraline was reintroduced for 2 months without any benefits noted. |

| Yuan et al., 2022 [38] | Case Report | 1 male | A 42-year-old male with a history of papillary thyroid carcinoma status post total thyroidectomy and left modified radical neck dissection with a full course of radioactive iodine treatment presented to a psychiatric clinic for persistent fatigue, increased anxiety, and irritability. A screening measure indicated a moderate level of depression, and his levothyroxine requirements were closely followed by his endocrinologist. The patient was started on bupropion XL 150 mg once daily, but this was discontinued due to increased irritability. Sertraline 50 mg once daily was started with improvements of his symptoms, but he also developed hypersexuality (including increased sex drive, constant sexual thoughts, and compulsive masturbation throughout the day) as well as delayed ejaculation. The patient was then trialed on duloxetine 30 mg one daily and then escitalopram but elected to restart sertraline 50 mg daily because he felt that the side effects outweighed the risks. No sexual symptoms were noted during this second trial of sertraline. |

| Stachelek et al., 2025 [46] | Case Series | 3 males | Three male participants were seen in a urology clinic and treated with high frequency electrical stimulation and low intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy for a total of 16 weeks for sexual dysfunction induced by SSRI or finasteride use. Mild to moderate improvements in sexual function was noted in all three participants. |

| Winder et al., 2024 [25] | Non-randomized, open label trial | 135 males | A non-randomized, open label study of 77 incarcerated males in the United Kingdom with sexual convictions were treated with anti-androgens (n = 8) or SSRIs (n = 69). 66 received Fluoxetine, 2 Paroxetine, and 1 Sertraline. 58 participants were assigned to the control group for comparison. Both medicated groups demonstrated levels of problematic sexual arousal 3 months post-baseline, the comparison group did not. |

| Lorenz 2020 [57] | Observational Cohort Study | 610 people (207 males, 403 females) | An observational survey study of 610 young adults assessed childhood and current mental health, detailing past antidepressant and other psychopharmaceutical prescription history before the age of 16. For women, childhood SSRI use was associated with significantly lower solitary sexual desire, desire for an attractive other, and frequency of masturbation. No differences in women’s partnered sexual desire or sexual activity was noted. Childhood use of non-SSRI antidepressants or non-antidepressant psychiatric medications were not associated with adult sexual desire/behavioral changes in either women or men. |

| Melcangi et al., 2017 [63] | Observational Cohort Study | 16 males | Small observational cohort study of 16 young male patients aged 22–44 with post-finasteride syndrome. 50% screened positive for depression after developing PFS. All patients showed some form of erectile dysfunction with 10 (62.5%) men affected severely and 6 (37.5%) with mild-moderate forms. This cohort of patients showed a low score for orgasmic function, sexual desire and overall satisfaction domains, compared to the general population. The levels of some neuroactive steroids analysed in CSF of PFS patients were significantly different versus those in healthy controls. In particular, the levels of pregnenolone, as well as of its further metabolites, progesterone and dihydroprogesterone, were significantly decreased in CSF of PFS patients. On the contrary, the levels of DHEA and testosterone were significantly increased. |

| Safak et al., 2025 [11] | Observational Cohort Study | 451 people (291 males, 161 females) | An observational survey study using the Psychotropic-related Sexual Dysfunction Questionnaire comprised 452 people (291 males and 161 females). Sexual dysfunction was highly prevalent among both females (88.7%) and males (84.5%). Significant differences were observed based on antidepressant type with bupropion users experiencing lower levels of sexual dysfunction compared to others using SSRIs, SNRIs, or vortioxetine. No significant differences were found for males. |

| Landgren et al., 2020 [64] | Randomized clinical trial | 52 males | In a randomized clinical trial of 52 males with pedophilic disorder, treatment with degarelix was found to significantly reduce the risk for committing child sexual abuse 2 weeks after initial injection. This finding suggests that degarelix may serve as a rapid-onset, risk-reducing medication for men with pedophilic disorder. The main adverse reactions were local injection site reactions and elevated hepatobiliary enzyme levels. 2 (8%) of the participants in the degarelix group reported suicidal ideation, but post hoc analysis found no statistically significant differences between suicidality when comparing the degarelix and placebo group. |

| Alipour-Kivi et al., 2024 [31] | Randomized, open-label, controlled trial | 50 males | A small randomized, open-label, controlled trial with 63 patients. 32 patients were assigned to drug holiday groups and 31 were assigned to the control group. 50 patients completed the trial (25 in each group). Drug holidays from SSRIs significantly improved erection, ejaculation, satisfaction, and the overall sexual health of participants. No significant changes were observed in the mental health of drug holiday participants. |

| Ben-Sheetrit et al., 2023 [13] | Retrospective Cohort Study | 12,302 males | A 19-year retrospective cohort analysis was conducted by querying a local hospital database for chart information on males aged 21 to 49 with erectile dysfunction (defined as a prescription of phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors). Those with erectile dysfunction were grouped based on whether they used serotonergic antidepressants or not. Serotonergic antidepressants were associated with significantly higher rates of erectile dysfunction. The prevalence of PSSD was estimated to be 0.46%. |

| Luca et al., 2022 [42] | Retrospective Cohort Study | 13 males | A retrospective cohort study of 13 males aged 29.53 ± 4.57 years with PSSD were tentatively treated based on their symptoms using an antidepressant with a dopaminergic/noradrenergic profile or antagonizing/positively modulating the serotonergic system (i.e., with fewer or no known SD side effects) as well as nutraceuticals and/or PDE5 inhibitors. Vortioxetine was the most commonly used and effective treatment out of all medications used. |

| Waraich et al., 2020 [30] | Retrospective Cohort Study | 43 males | A retrospective chart review from 2009 to 2019 was performed finding 43 male patients who met the criteria for PSSD, approximately 4% of the male patients seen during that timeframe. 40 (93%) of these male patients had erectile dysfunction. Consistent with other reports of PSSD, the patients observed to have PSSD are young (mean age 31) with severe erectile dysfunction affecting most patients. |

| Lalegani et al., 2023 [28] | Randomized, open-label, controlled trial | 50 females | A small randomized, open-label, controlled trial consisted of 55 female participants (drug holiday group n = 28, control group n = 27) examining the effects of drug holidays on female sexual function and mental health status. A total of 50 participants completed the trial (25 per group), the drug holiday group experienced significant improvements in arousal, desire, orgasm, satisfaction, lubrication, and overall sexual health. |

| Zeiss et al., 2024 [29] | Retrospective Pharmacovigilance Study | 91,195 safety report cases | A study examining the World Health Organization’s database of individual case safety reports. A total number of 91,195 cases were examined from the database regarding desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual dysfunction. Using this data, the authors were able to calculate odds ratios with their respective 95% confidence intervals for desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual dysfunction. Serotonergic agents such as SSRIs and SNRIs were among the most frequently reported group of antidepressants linked to sexual dysfunction, with SSRIs such as paroxetine having higher reporting odd ratios (RORs) than TCAs such as clomipramine (Paroxetine ROR: 21.78 (20.1–23.59), clomipramine ROR: 4.94 (3.25–7.5)) |

| Pirani et al., 2024 [53] | Observational Cohort Study | 2179 survey participants | A survey study with 2179 participants which examined US/Canada sexual and gender minority youth aged 15 to 29. 574 (26.3%) of participants reported genital hypoesthesia, these participants were generally older and more likely to report their assigned sex at birth being male, having undergone hormonal therapy previously, and have a psychiatric drug history. The frequency of persistent post-treatment genital hypoesthesia among antidepressant users was 13.2% (93/707) compared to 0.9% (1/102) among users of other medications. An adjusted odds ratio was 14.2. |

| Butler et al., 2010 [32] | Non-randomized, open label trial | 20 males | An open label clinical trial examining the effectiveness of a three-month trial of sertraline on controlling impulsive violent behaviors in individuals with a history of violent offending (at least one prior conviction for a violent offense). 34 individuals started the trial with 20 completing the three-month intervention, reductions in impulsivity, irritability, anger, assault, verbal-assault, indirect-assault, and depression were noted. All 20 participants who completed the three-month trial requested to continue sertraline under the supervision of their own medical practitioner. The findings of this study suggest that treating impulsive, violent individuals in a forensic setting with SSRIs can be beneficial for patient mood and to attenuate violent behaviors. |

| Patacchini et al., 2020 [27] | Observational Cohort Study | 135 participants | An online survey study which examined 135 participants (115 males, average age 31.9 with a SD of 8.9 years) for self-declared PSSD. The survey found that PSSD was more common in younger, heterosexual males after exposure to SSRI/SNRI at relatively high doses. 118 subjects had symptoms both during and after SSRI/SNRI administration while only 17 participants experienced symptoms of PSSD after SSRI/SNRI treatment. The authors concluded that PSSD is a complex iatrogenic syndrome in need for further study. |

| Studt et al., 2021 [49] | Observational Cohort Study | 239 participants | A survey study conducted through online support groups for individuals with PSSD, 239 survey responses were recorded. The majority of respondents reported a history of SSRI use (92%) compared to only SNRI or atypical antidepressant use (8%). The severity of symptoms improved in 45% of respondents and worsened/remained the same for 37% of respondents after discontinuing treatment with SSRIs. Only 12% of respondents reported receiving counseling regarding potential sexual dysfunction while taking antidepressants. Most rated the effect of PSSD on their quality of life as severely negative (59%) or very negative (23%). |

| Rice et al., 2025 [51] | Observational Cohort Study | 10 participants | 10 participants were recruited through a patient advocacy group to participate in private, semi-structured interviews. 8 main themes emerged upon phenomenological analysis to describe the participants’ experiences with PSSD. Individuals with PSSD undergo psychological, physical, and sexual effects of withdrawal that cause suffering, hopelessness, and alienation. The current lack of understanding, awareness, and informed consent or acceptance among healthcare providers about PSSD worsens the negative experiences associated with PSSD and contributes to an overall lack of trust in physicians and/or medicine in general. |

| Issa et al., 2025 [9] | Retrospective Cohort Study | 234,217 participants | A retrospective study based on the Stockholm Sodium Cohort data of 1,632,249 individuals. First-time users of SSRI/venlafaxine were included, comprising 234,217 participants of whom 39,999 developed profound hyponatremia at least once. The incidence of profound hyponatremia among individuals 65 to 79 years old and greater than 80 years old were 3% and 4%, respectively. The odds ratio for profound hyponatremia was 4.29 (95% CI: 3.34–5.52) within the first 3 months after SSRI/venlafaxine initiation. After 1 year the aOR was 1.30 (95% CI: 0.97–1.75). During the first 2 weeks after initiation treatment, the aOR was 10.06 (95% CI: 5.97–17.00). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shaw, J.; Lai, C.; Bota, P.; Le, A.; Andricioaei, A.; Tran, T.; Allee, T. The Off-Label Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Sexual Behavior Management: Risks and Considerations. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192433

Shaw J, Lai C, Bota P, Le A, Andricioaei A, Tran T, Allee T. The Off-Label Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Sexual Behavior Management: Risks and Considerations. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192433

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaw, Jonathan, Charles Lai, Peter Bota, Andrew Le, Anton Andricioaei, Theodore Tran, and Tina Allee. 2025. "The Off-Label Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Sexual Behavior Management: Risks and Considerations" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192433

APA StyleShaw, J., Lai, C., Bota, P., Le, A., Andricioaei, A., Tran, T., & Allee, T. (2025). The Off-Label Use of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors for Sexual Behavior Management: Risks and Considerations. Healthcare, 13(19), 2433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192433