Determinants of Psychosocial and Mental Health Risks of Multicultural Adolescents: A Multicultural Adolescents Panel Study 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

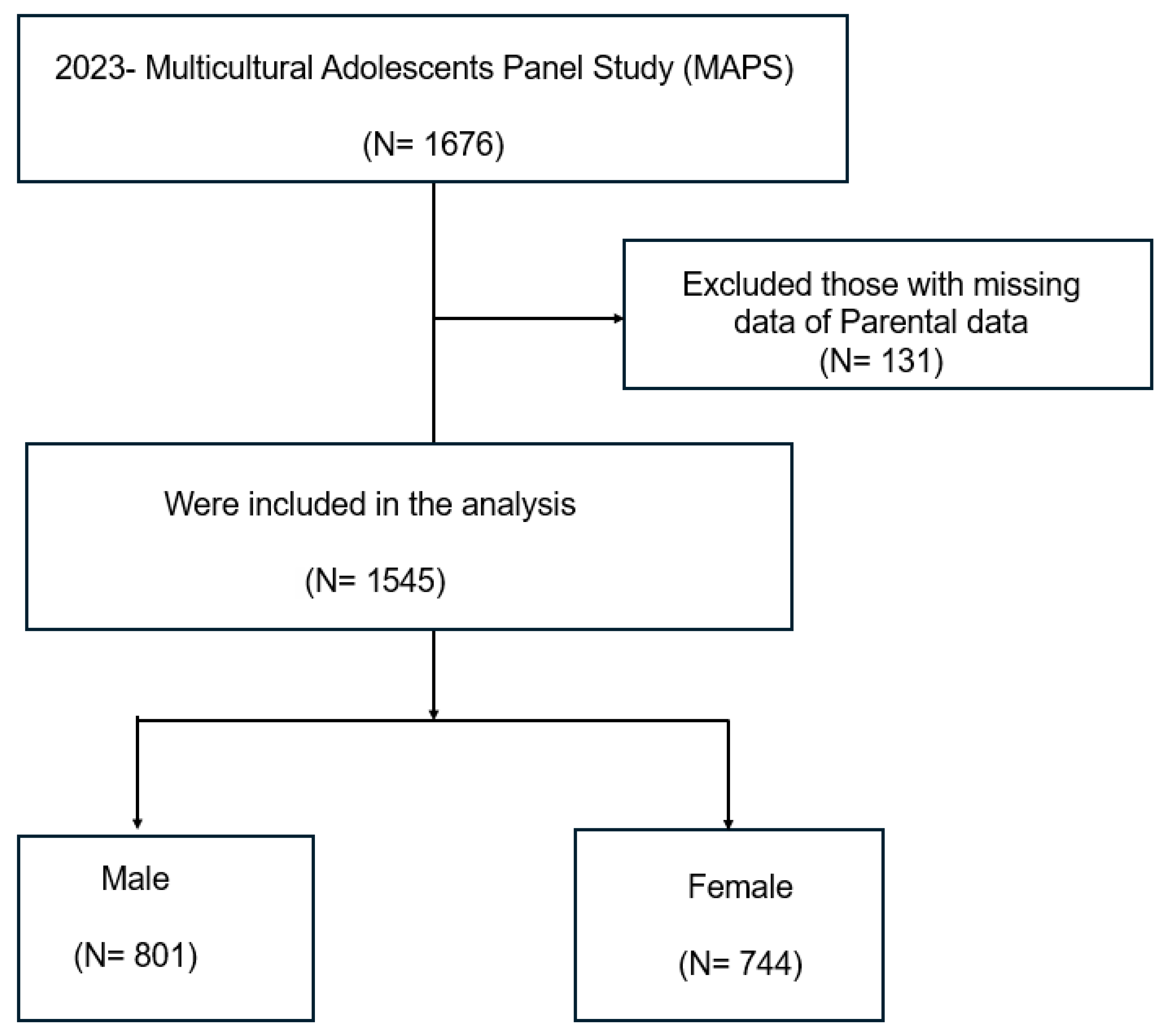

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Outcome Variables

2.3.2. Covariates

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Demographic Characteristics of Female Students

3.2. Relationship Between Psychosocial and Mental Health Risk and General Characteristics of Multicultural Adolescents

3.3. Correlation Between Psychosocial and Mental Health Risks of Multiculture Adolescents

3.4. Factors Affecting the Psychosocial and Mental Health Risks of Multiculture Adolescents

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Lund, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Baingana, F.; Bolton, P.; Unutzer, J. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 2018, 392, 1553–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Sowislo, J.F.; Orth, U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieling, C.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Belfer, M.; Conti, G.; Ertem, I.; Omigbodun, O.; Rahman, A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E. Mental health and related factors among adolescents from multicultural families: Evidence from MAPS. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2023, 29, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S. Cultural identity, discrimination, and adolescent adjustment in South Korea. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2023, 28, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. Developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms in multicultural adolescents. Res. Community Public Health Nurs. 2024, 35, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. Identity development and peer relationships among multicultural adolescents in South Korea. J. Adolesc. Res. 2018, 33, 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.C.; Min, A. Peer Victimization, Supportive Parenting, and Depression Among Adolescents in South Korea: A Longitudinal Study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 43, e100–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J. Peer relationships, school adjustment, and multicultural family support services in South Korea. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1301294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K.H.; Coplan, R.J.; Bowker, J.C. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafary, R.; Park, S.; Lee, J. Maternal education and adolescent mental health among multicultural families. PLOS Ment. Health 2025, 2, e0000356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 90, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Lim, M. Stress, self-esteem, and life satisfaction as predictors of adolescent mental health. J. Korean Soc. Health Educ. Promot. 2022, 39, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2005, 29, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potochnick, S.R.; Perreira, K.M. Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010, 198, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W. The development of self-esteem. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 23, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; He, J.P.; Burstein, M.; Swendsen, J.; Avenevoli, S.; Case, B.; Olfson, M. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 50, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Leventhal, B. Bullying and suicide. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2008, 20, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbeater, B.J.; Blatt, S.J.; Quinlan, D.M. Gender-linked vulnerabilities to depressive symptoms, stress, and problem behaviors in adolescents. J. Res. Adolesc. 1995, 5, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfield, S.; Smith, D. Gender and mental health: Do men and women have different amounts or types of problems? In A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health: Social Contexts, Theories, and Systems; Scheid, T.L., Brown, T.N., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 256–267. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, U.; Robins, R.W. Understanding the link between low self-esteem and depression. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 22, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, A.E.; Fend, H.A.; Allemand, M. Testing the vulnerability and scar models of self-esteem and depressive symptoms from adolescence to middle adulthood and across generations. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Haynie, D.; Palla, H.; Lipsky, L.; Iannotti, R.J.; Simons-Morton, B. Assessment of adolescent weight status: Similarities and differences between CDC, IOTF, and WHO references. Prev. Med. 2016, 87, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Siu, A.; Tse, W.S. The role of high parental expectations in adolescents’ academic performance and depression in Hong Kong. J. Fam. Issues 2018, 39, 2505–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, T. Social stigma, ego-resilience, and depressive symptoms in adolescent school dropouts. J. Adolesc. 2020, 85, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latner, J.D.; Stunkard, A.J.; Wilson, G.T. Stigmatized students: Age, sex, and ethnicity effects in the stigmatization of obesity. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y. Multicultural families and child development in South Korea: Policy and practice. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 2017, 11, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. The Influence of Mothers’ Educational Level on Children’s Comprehensive Quality. J. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2023, 8, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 801 | 51.84 |

| Female | 744 | 48.16 | |

| Age | 13 | 15 | 0.97 |

| 14 | 1460 | 94.5 | |

| 15 | 64 | 4.14 | |

| 16 | 6 | 0.39 | |

| Region | Capital and metropolitan city | 471 | 30.5 |

| metropolitan areas | 821 | 53.1 | |

| Other | 253 | 16.4 | |

| Mother nationality | 1.0 | 524 | 33.9 |

| 2.0 | 338 | 21.9 | |

| Father nationality | 1.0 | 1305 | 84.5 |

| 2.0 | 144 | 9.3 | |

| Mother age | 30 s | 639 | 41.36 |

| 40 s | 735 | 47.57 | |

| ≥50 s | 171 | 11.07 | |

| Father age | 30 s | 30 | 1.94 |

| 40 s | 12 | 0.78 | |

| ≥50 s | 1503 | 97.28 | |

| Mother education | Middle school or less | 471 | 30.49 |

| High school | 690 | 44.66 | |

| Undergraduate and over | 384 | 24.85 | |

| Father education | Middle school or less | 216 | 13.98 |

| High school | 934 | 60.45 | |

| Undergraduate and over | 395 | 25.57 | |

| Mother job | Professional or experts | 223 | 14.43 |

| Technician or labor | 487 | 31.52 | |

| Others * | 835 | 54.05 | |

| Father job | Professional or experts | 319 | 20.65 |

| Technician or labor | 512 | 33.14 | |

| Others | 714 | 46.21 | |

| Monthly Income (KRW 10,000) | <300 | 345 | 22.07 |

| 301–600 | 1091 | 70.61 | |

| 601–900 | 99 | 6.41 | |

| >901 | 14 | 0.91 | |

| BMI | Underweight | 392 | 25.37 |

| Normal | 911 | 58.96 | |

| Overweight | 190 | 12.3 | |

| Obesity | 52 | 3.37 | |

| Mental health problems (M ± SD) | Aggression | 1.825 | 0.629 |

| Social withdrawal | 2.183 | 0.778 | |

| Depression | 1.559 | 0.580 | |

| Self-esteem | 3.211 | 0.570 | |

| Variables | Social Withdrawal | Depression | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | F/t | p | M | SD | F/t | p | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 2.171 | 0.750 | 0.405 | 0.525 | 1.524 | 0.540 | 5.991 | 0.014 |

| Female | 2.196 | 0.807 | 1.596 | 0.618 | ||||

| AGE | ||||||||

| 13 | 2.067 | 0.768 | 1.011 | 0.387 | 1.440 | 0.455 | 0.915 | 0.433 |

| 14 | 2.189 | 0.780 | 1.564 | 0.584 | ||||

| 15 | 2.115 | 0.733 | 1.494 | 0.504 | ||||

| 16 | 1.722 | 0.491 | 1.300 | 0.452 | ||||

| Region | ||||||||

| Capital and metropolitan | 2.064 | 0.776 | 15.956 | 0.000 | 1.528 | 0.561 | 1.888 | 0.170 |

| Metropolitan areas | 2.235 | 0.773 | 1.572 | 0.588 | ||||

| other | 2.352 | 0.808 | 1.577 | 0.573 | ||||

| Mother nationality | ||||||||

| Korean | 2.264 | 0.874 | 0.262 | 0.608 | 1.458 | 0.548 | 0.732 | 0.392 |

| Non-Korean | 2.182 | 0.776 | 1.560 | 0.580 | ||||

| Father nationality | ||||||||

| Korea | 2.182 | 0.777 | 0.009 | 0.925 | 1.571 | 0.591 | 3.540 | 0.060 |

| China | 2.187 | 0.781 | 1.497 | 0.519 | ||||

| Mother age | ||||||||

| 30 s | 2.172 | 0.801 | 0.120 | 0.887 | 1.555 | 0.584 | 0.229 | |

| 40 s | 2.191 | 0.762 | 1.556 | 0.573 | ||||

| ≥50 s | 2.191 | 0.761 | 1.587 | 0.595 | ||||

| Father age | ||||||||

| 30 s | 2.089 | 0.694 | 0.370 | 0.691 | 1.687 | 0.698 | 2.127 | |

| 40 s | 2.306 | 0.881 | 1.833 | 0.894 | ||||

| ≥50 s | 2.184 | 0.779 | 1.554 | 0.574 | ||||

| Mother education | ||||||||

| Middle school or less | 2.275 | 0.798 | 5.017 | 0.007 | 1.604 | 0.592 | 2.188 | 0.112 |

| High school | 2.129 | 0.748 | 1.532 | 0.560 | ||||

| Undergraduate and over | 2.169 | 0.797 | 1.552 | 0.598 | ||||

| Father education | ||||||||

| Middle school or less | 2.204 | 0.769 | 0.619 | 0.538 | 1.634 | 0.600 | 3.080 | 0.046 |

| High school | 2.194 | 0.775 | 1.561 | 0.581 | ||||

| Undergraduate and over | 2.146 | 0.788 | 1.513 | 0.563 | ||||

| Mother job | ||||||||

| Professional or experts | 2.172 | 0.801 | 0.325 | 0.722 | 1.552 | 0.615 | 0.104 | 0.002 |

| Technician or labor | 2.207 | 0.760 | 1.552 | 0.561 | ||||

| Others | 2.172 | 0.782 | 1.565 | 0.581 | ||||

| Father job | ||||||||

| Professional or experts | 2.186 | 0.777 | 0.056 | 0.945 | 1.542 | 0.572 | 0.310 | 0.734 |

| Technician or labor | 2.174 | 0.780 | 1.573 | 0.582 | ||||

| Others | 2.189 | 0.777 | 1.556 | 0.582 | ||||

| Monthly Income | ||||||||

| <300 | 2.230 | 0.807 | 5.017 | 0.007 | 1.610 | 0.584 | 2.188 | 0.112 |

| 301–600 | 2.162 | 0.777 | 1.547 | 0.582 | ||||

| 601–900 | 2.229 | 0.709 | 1.517 | 0.535 | ||||

| >901 | 2.405 | 0.573 | 1.557 | 0.652 | ||||

| BMI | ||||||||

| Underweight | 2.200 | 0.766 | 0.600 | 0.615 | 1.591 | 0.593 | 0.865 | 0.459 |

| Normal | 2.169 | 0.781 | 1.541 | 0.565 | ||||

| Overweight | 2.181 | 0.764 | 1.565 | 0.574 | ||||

| Obesity | 2.308 | 0.863 | 1.612 | 0.742 | ||||

| Aggression | Social Withdrawal | Depression | Self-Esteem | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aggression | 1 | 0.382 ** | 0.492 ** | −0.119 ** |

| Social withdrawal | 0.382 ** | 1 | 0.537 ** | −0.211 ** |

| Depression | 0.492 ** | 0.537 ** | 1 | −0.373 ** |

| Self-esteem | −0.119 ** | −0.211 ** | −0.373 ** | 1 |

| Variables | Social Withdrawal | Depression | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | 95%CI | t | p | Estimate | SE | 95%CI | t | p | |||

| Intercept | 1.583 | 0.850 | 0.002 | 0.332 | 1.862 | 0.049 | 1.10896 | 0.6358 | −0.1382 | 2.35614 | 1.7441 | 0.081 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Female | 0.019 | 0.040 | −0.0603 | 0.0982 | 0.469 | 0.639 | 0.076 | 0.030 | 0.016 | 0.135 | 2.509 | 0.012 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 13 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 14 | 0.124 | 0.202 | −0.272 | 0.5214 | 0.615 | 0.539 | 0.124 | 0.151 | −0.172 | 0.421 | 0.821 | 0.028 |

| 15 | 0.084 | 0.224 | −0.355 | 0.5237 | 0.375 | 0.008 | 0.053 | 0.168 | −0.276 | 0.381 | 0.315 | 0.753 |

| 16 | 0.379 | 0.379 | −1.1221 | 0.363 | 0.251 | 0.317 | 0.469 | 0.283 | 0.324 | 0.786 | 0.598 | 0.050 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Capital | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Metropolitan | 0.141 | 0.045 | 0.052 | 0.229 | 3.110 | 0.002 | 0.041 | 0.034 | −0.025 | 0.107 | 1.211 | 0.226 |

| Others | 0.287 | 0.062 | 0.164 | 0.409 | 4.608 | <0.001 | 0.040 | 0.047 | −0.051 | 0.131 | 0.851 | 0.395 |

| Mother nationality | ||||||||||||

| Korean | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Non-Korean | 0.067 | 0.167 | −0.3948 | 0.261 | 0.399 | 0.690 | 0.069 | 0.125 | −0.175 | 0.314 | 0.555 | 0.579 |

| Father nationality | ||||||||||||

| Korean | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Non-Korean | 0.011 | 0.055 | −0.1191 | 0.097 | 0.192 | 0.847 | 0.069 | 0.041 | −0.149 | 0.012 | 1.660 | 0.097 |

| Mother age | ||||||||||||

| 30 s | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 40 s | 0.071 | 0.045 | −0.0169 | 0.158 | 1.582 | 0.114 | 0.033 | 0.033 | −0.032 | 0.098 | 0.989 | 0.323 |

| ≥50 s | 0.079 | 0.070 | 0.0572 | 0.082 | 1.140 | 0.048 | 0.063 | 0.052 | −0.039 | 0.165 | 1.213 | 0.225 |

| Father age | ||||||||||||

| 30 s | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 40 s | 0.241 | 0.266 | −0.2802 | 0.7629 | 0.908 | 0.364 | 0.172 | 0.199 | −0.217 | 0.562 | 0.867 | 0.386 |

| ≥50 s | 0.039 | 0.146 | 0.02469 | 0.0425 | 0.269 | 0.018 | 0.158 | 0.109 | −0.371 | 0.056 | 1.444 | 0.149 |

| Mother education | ||||||||||||

| Middle school or less | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| High school | 0.142 | 0.049 | −0.238 | −0.046 | 2.912 | 0.004 | 0.062 | 0.037 | −0.133 | 0.0095 | 1.701 | 0.089 |

| Undergraduate and over | 0.100 | 0.062 | −0.221 | 0.022 | 1.596 | 0.111 | 0.023 | 0.047 | −0.115 | 0.0679 | 0.504 | 0.615 |

| Father education | ||||||||||||

| Middle school or less | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| High school | 0.037 | 0.061 | −0.082 | 0.157 | 0.607 | 0.544 | 0.057 | 0.046 | −0.033 | 0.147 | 1.238 | 0.216 |

| Undergraduate and over | 0.011 | 0.073 | −0.153 | 0.132 | 0.144 | 0.885 | 0.108 | 0.055 | 0.001 | 0.216 | 1.974 | 0.049 |

| Mother job | ||||||||||||

| Professional or experts | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Technician or labor | 0.015 | 0.068 | −0.1179 | 0.147 | 0.217 | 0.828 | 0.024 | 0.051 | −0.123 | 0.074 | 0.483 | 0.629 |

| Others | 0.007 | 0.062 | −0.1294 | 0.1145 | 0.119 | 0.905 | 0.002 | 0.047 | −0.089 | 0.092 | 0.032 | 0.974 |

| Father job | ||||||||||||

| Professional or experts | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Technician or labor | 0.064 | 0.059 | −0.180 | 0.051 | 1.088 | 0.277 | 0.004 | 0.044 | −0.082 | 0.090 | 0.095 | 0.924 |

| Others | 0.026 | 0.056 | −0.135 | 0.083 | 0.462 | 0.644 | 0.017 | 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.411 | 0.011 |

| Monthly Income | ||||||||||||

| <300 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 301–600 | 0.495 | 0.787 | −1.047 | 2.038 | 0.630 | 0.529 | 0.468 | 0.588 | −0.631 | 1.676 | 0.796 | 0.046 |

| 601–900 | 0.438 | 0.786 | −1.104 | 1.98 | 0.557 | 0.578 | 0.450 | 0.591 | −0.685 | 1.621 | 0.761 | 0.447 |

| >901 | 0.526 | 0.791 | −1.024 | 2.076 | 0.665 | 0.506 | 0.517 | 0.608 | −0.709 | 1.609 | 0.850 | 0.395 |

| BMI | ||||||||||||

| Underweight | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Normal | 0.034 | 0.047 | −0.126 | 0.057 | 0.731 | 0.465 | 0.050 | 0.035 | −0.119 | 0.019 | 1.420 | 0.156 |

| Overweight | 0.044 | 0.069 | −0.179 | 0.092 | 0.628 | 0.530 | 0.024 | 0.052 | −0.125 | 0.077 | 0.461 | 0.645 |

| Obesity | 0.088 | 0.117 | −0.141 | 0.316 | 0.750 | 0.454 | 0.027 | 0.087 | −0.144 | 0.197 | 0.304 | 0.761 |

| Predictor | Self-Esteem | Aggression | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | 95%CI | t | p | Estimate | SE | 95%CI | t | p | |||

| Intercept | 3.363 | 0.623 | 2.1404 | 4.58695 | 5.393 | <0.001 | 1.755 | 0.687 | 0.4064 | 3.10408 | 2.552 | 0.011 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Female | −0.0893 | 0.0296 | −0.1474 | −0.03118 | −3.0137 | 0.003 | −0.011 | 0.033 | −0.075 | 0.053 | −0.331 | 0.741 |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 13 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 14 | −0.151 | 0.148 | −0.442 | 0.14 | −1.018 | 0.309 | 0.054 | 0.164 | −0.267 | 0.375 | 0.329 | 0.743 |

| 15 | −0.152 | 0.164 | −0.475 | 0.169 | −0.928 | 0.353 | 0.129 | 0.181 | −0.227 | 0.484 | 0.710 | 0.478 |

| 16 | 0.389 | 0.277 | −0.155 | 0.934 | 1.403 | 0.161 | −0.092 | 0.306 | −0.693 | 0.509 | −0.300 | 0.764 |

| Region | ||||||||||||

| Capital | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Metropolitan | −0.069 | 0.033 | −0.134 | −0.004 | −2.093 | 0.037 | 0.073 | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.145 | 1.986 | 0.047 |

| Others | −0.036 | 0.045 | 0.125 | 0.053 | −0.789 | 0.043 | −0.038 | 0.050 | −0.137 | 0.060 | −0.763 | 0.445 |

| Mother nationality | ||||||||||||

| Korean | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Non-Korean | 0.071 | 0.122 | −0.1696 | 0.31156 | 0.578 | 0.563 | 0.021 | 0.011 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 1.964 | 0.004 |

| Father nationality | ||||||||||||

| Korean | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Non-Korean | 0.055 | 0.04 | −0.0241 | 0.13509 | 1.368 | 0.031 | 0.094 | 0.044 | 0.008 | 0.180 | 2.1136 | 0.036 |

| Mother age | ||||||||||||

| 30 s | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 40 s | 0.056 | 0.0327 | 0.018 | 0.089 | 1.737 | 0.083 | 0.042 | 0.036 | −0.028 | 0.113 | 1.173 | 0.241 |

| ≥50 s | 0.075 | 0.0511 | 0.045 | 0.098 | 1.468 | 0.142 | 0.002 | 0.056 | −0.109 | 0.112 | 0.033 | 0.973 |

| Father age | ||||||||||||

| 30 s | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 40 s | 0.276 | 0.195 | −0.1057 | 0.65933 | 1.419 | 0.156 | 0.308 | 0.215 | −0.114 | 0.730 | 1.433 | 0.152 |

| ≥50 s | 0.256 | 0.107 | 0.046 | 0.46587 | 2.391 | 0.017 | 0.174 | 0.118 | −0.057 | 0.406 | 1.482 | 0.138 |

| Mother education | ||||||||||||

| Middle school or less | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| High school | 0.019 | 0.035 | −0.0507 | 0.09 | 0.548 | 0.584 | 0.003 | 0.039 | −0.081 | 0.074 | 0.09 | 0.928 |

| Undergraduate and over | 0.021 | 0.045 | −0.0686 | 0.11081 | 0.461 | 0.645 | 0.041 | 0.05 | −0.140 | 0.058 | 0.815 | 0.415 |

| Father education | ||||||||||||

| Middle school or less | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| High school | −0.0148 | 0.044 | −0.1028 | 0.07314 | 0.33 | 0.741 | −0.071 | 0.049 | −0.168 | 0.026 | −1.427 | 0.154 |

| Undergraduate and over | 5.671 | 0.0535 | −0.1044 | 0.1055 | 0.01 | 0.992 | −0.117 | 0.059 | −0.232 | −8.06 × 10−4 | −1.975 | 0.048 |

| Mother job | ||||||||||||

| Professional or experts | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Technician or labor | 0.028 | 0.049 | −0.0685 | 0.12602 | 0.58 | 0.562 | 0.096 | 0.055 | −0.011 | 0.204 | 1.764 | 0.078 |

| Others | −0.0232 | 0.045 | −0.1127 | 0.06625 | 0.509 | 0.611 | 0.050 | 0.050 | −0.049 | 0.149 | 0.995 | 0.32 |

| Father job | ||||||||||||

| Professional or experts | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Technician or labor | −0.0497 | 0.0433 | −0.1347 | 0.03524 | 1.148 | 0.251 | −0.050 | 0.048 | −0.144 | 0.044 | −1.047 | 0.295 |

| Others | −0.0397 | 0.041 | −0.1202 | 0.04074 | 0.968 | 0.333 | 0.079 | 0.045 | 0.009 | 0.168 | 1.767 | 0.017 |

| Monthly Income | ||||||||||||

| <300 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 301–600 | −0.251 | 0.577 | −1.383 | 0.880 | 0.435 | 0.663 | −0.071 | 0.636 | −1.318 | 1.177 | −0.111 | 0.912 |

| 601–900 | −0.202 | 0.577 | −1.334 | 0.929 | 0.35 | 0.726 | −0.131 | 0.636 | −1.379 | 1.116 | −0.207 | 0.836 |

| >901 | −0.106 | 0.580 | −1.244 | 1.031 | 0.183 | 0.855 | −0.098 | 0.639 | −1.352 | 1.156 | −0.153 | 0.879 |

| BMI | ||||||||||||

| Underweight | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Normal | 0.029 | 0.035 | −0.039 | 0.097 | 0.833 | 0.405 | 0.001 | 0.038 | −0.074 | 0.076 | 0.028 | 0.977 |

| Overweight | 0.082 | 0.051 | −0.018 | 0.181 | 1.602 | 0.109 | 0.152 | 0.056 | 0.042 | 0.263 | 2.716 | 0.007 |

| Obesity | 0.066 | 0.086 | 0.077 | 0.077 | 0.331 | 0.041 | 0.185 | 0.094 | 0.000 | 0.371 | 1.964 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Rajaguru, V. Determinants of Psychosocial and Mental Health Risks of Multicultural Adolescents: A Multicultural Adolescents Panel Study 2023. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192409

Kim J, Rajaguru V. Determinants of Psychosocial and Mental Health Risks of Multicultural Adolescents: A Multicultural Adolescents Panel Study 2023. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192409

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jeoungmi, and Vasuki Rajaguru. 2025. "Determinants of Psychosocial and Mental Health Risks of Multicultural Adolescents: A Multicultural Adolescents Panel Study 2023" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192409

APA StyleKim, J., & Rajaguru, V. (2025). Determinants of Psychosocial and Mental Health Risks of Multicultural Adolescents: A Multicultural Adolescents Panel Study 2023. Healthcare, 13(19), 2409. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192409