Motivational Interventions for Reducing Excessive Alcohol Consumption Among University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Sources

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- RCTs.

- Samples consisting of university students.

- Study objective: addressing alcohol consumption.

- Language: Spanish or English.

- Non-university populations.

- Studies evaluating the consumption of other substances.

- Grey literature, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

2.4. Study Selection Process

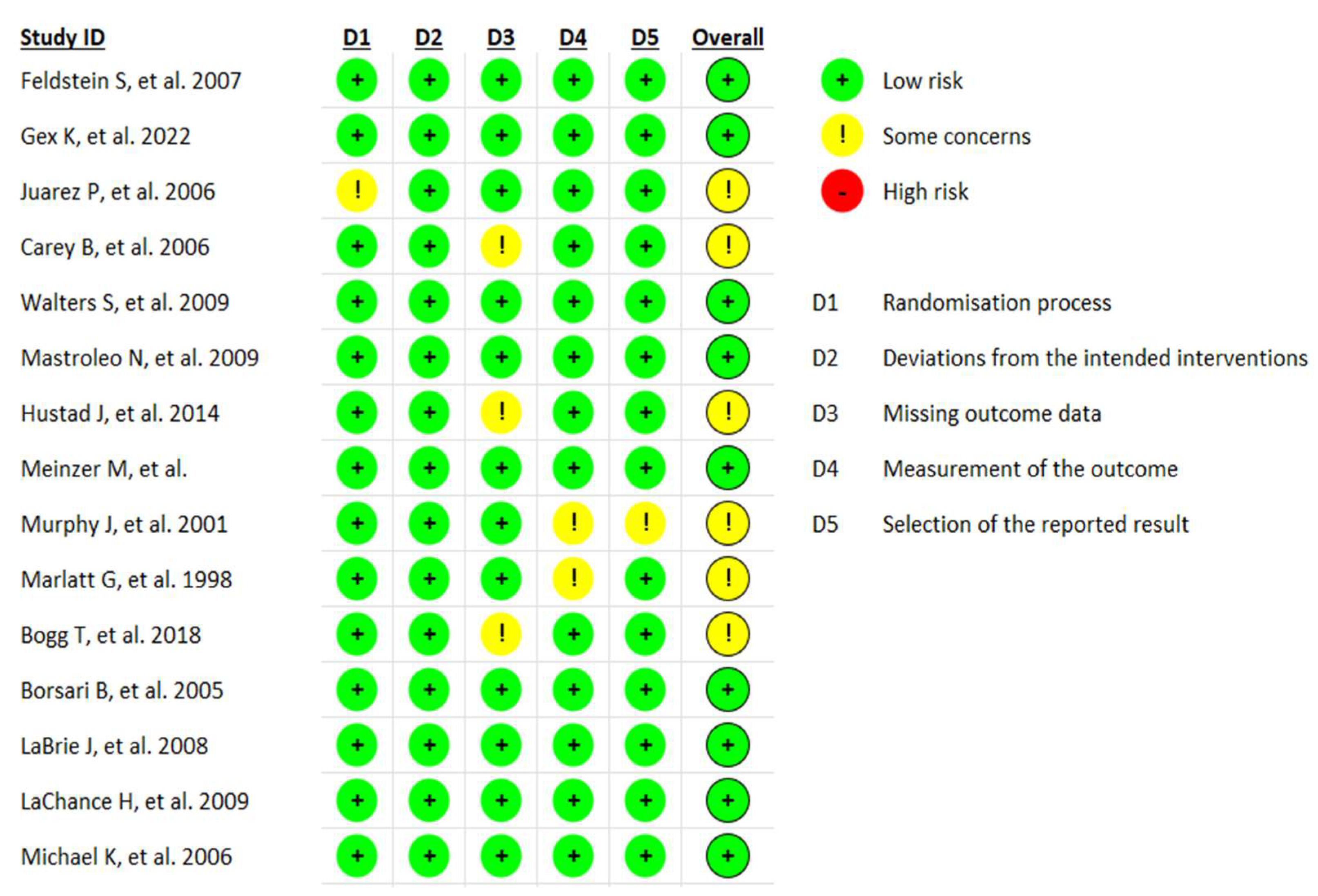

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

- (1)

- Randomisation process;

- (2)

- Deviations from intended interventions;

- (3)

- Missing outcome data;

- (4)

- Measurement of the outcome;

- (5)

- Selection of the reported result.

2.6. Data Extraction

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Selected Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias

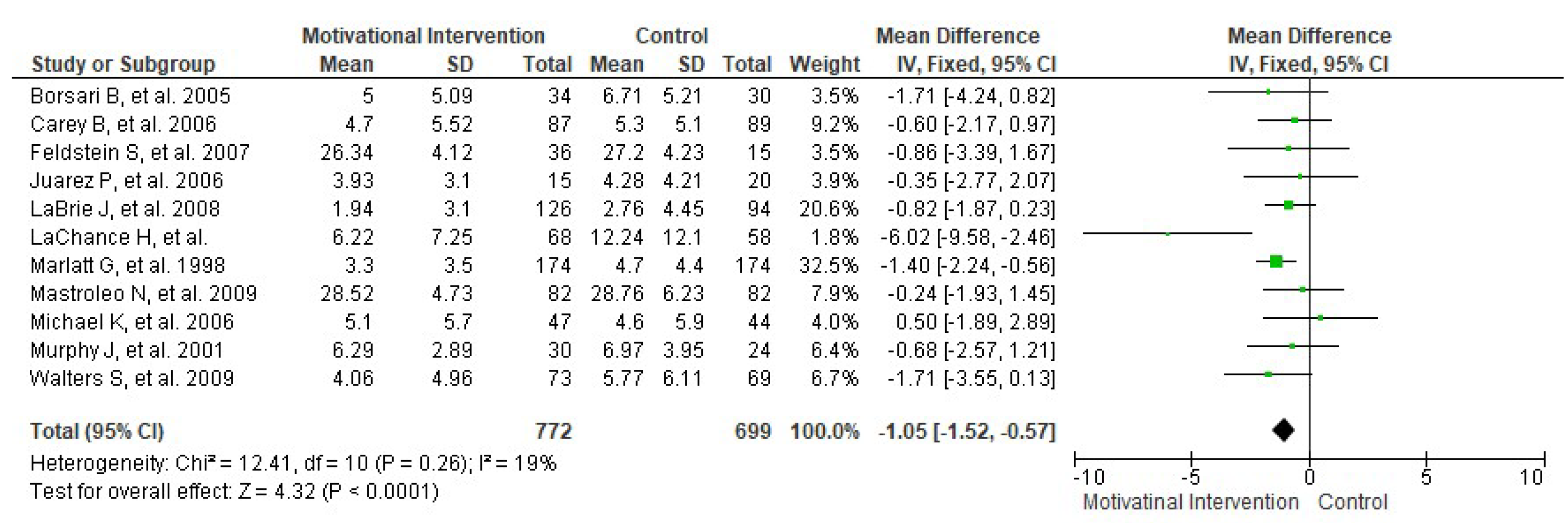

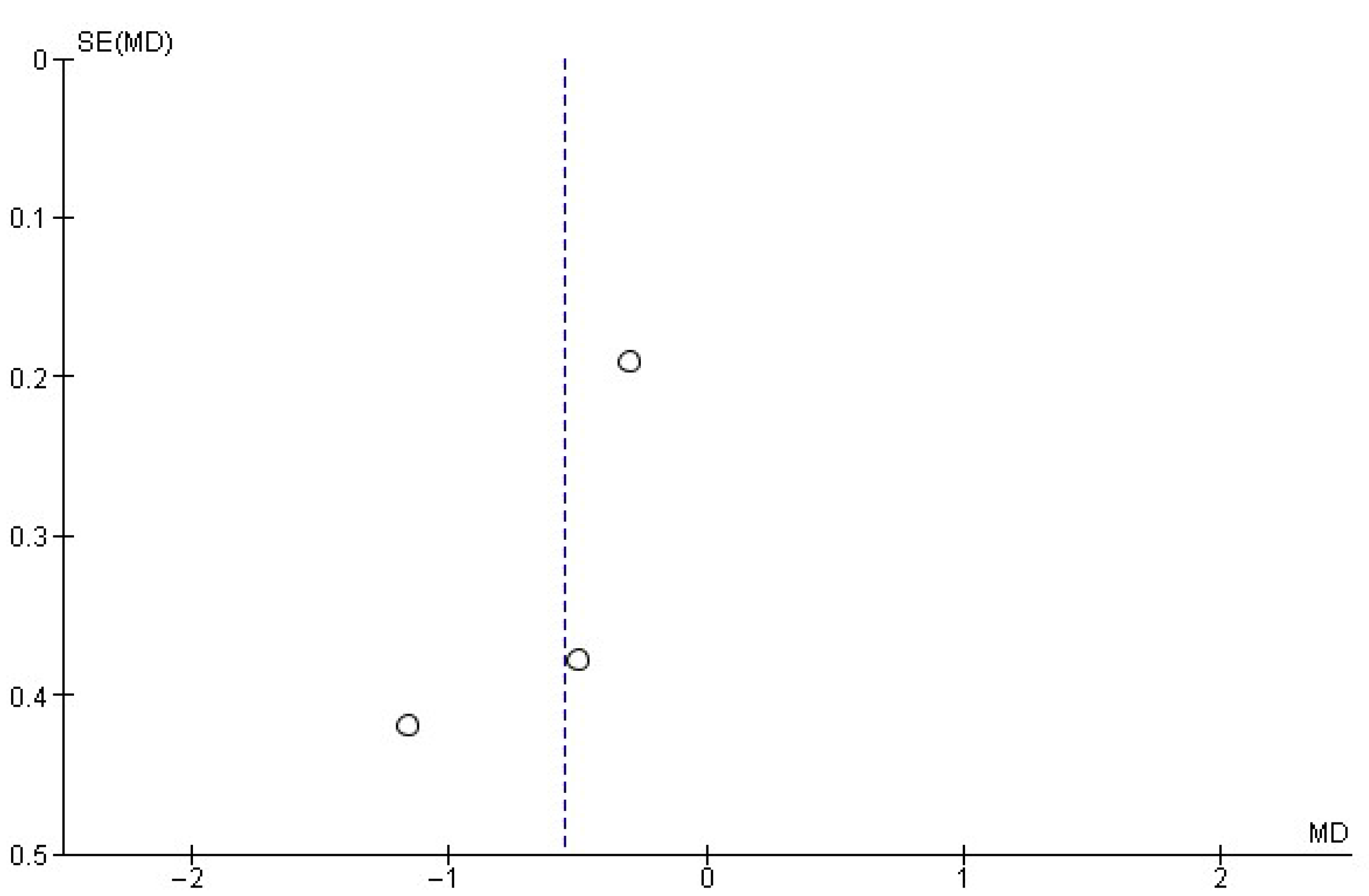

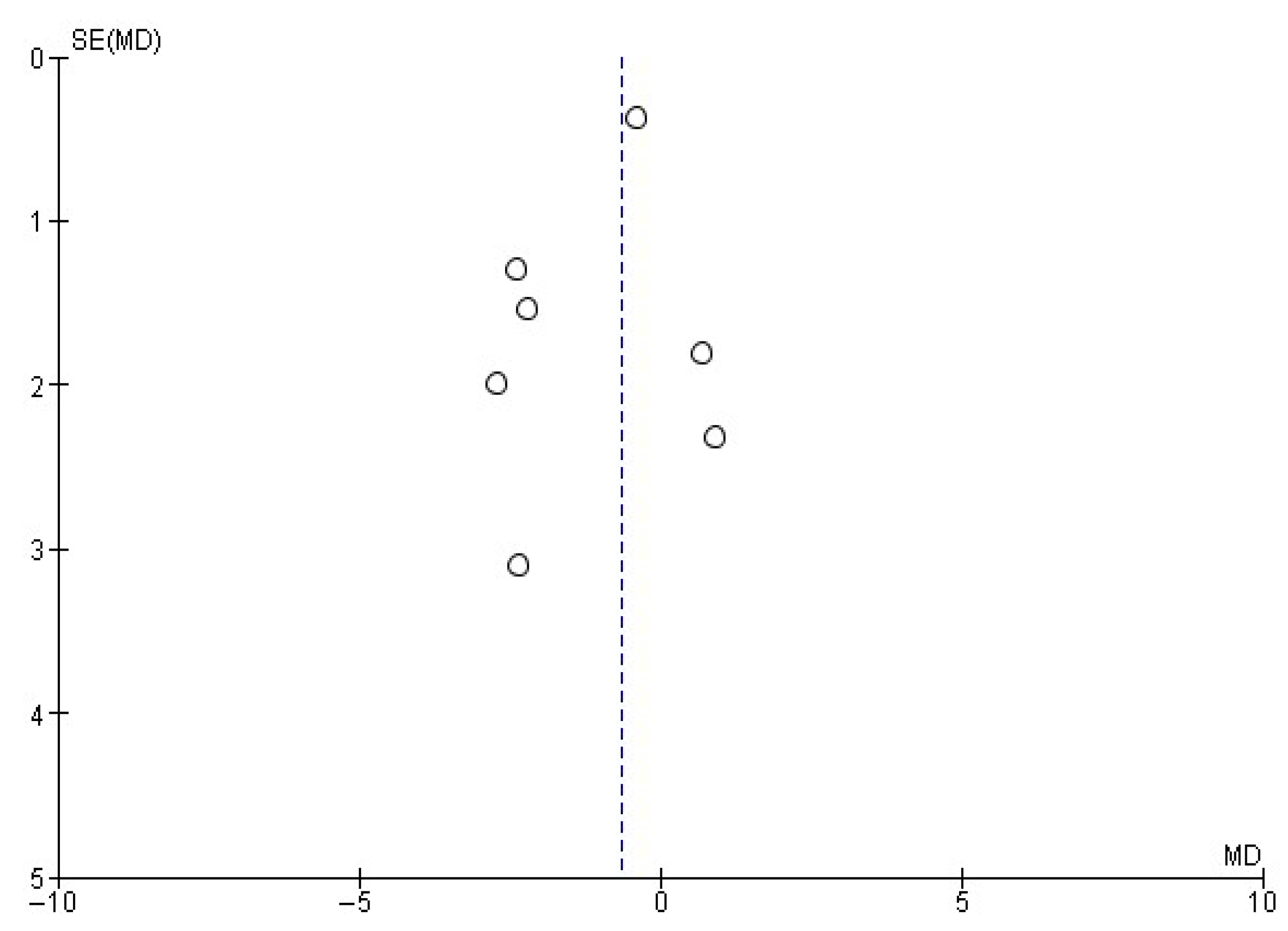

3.4. Alcohol Consumption Frequency

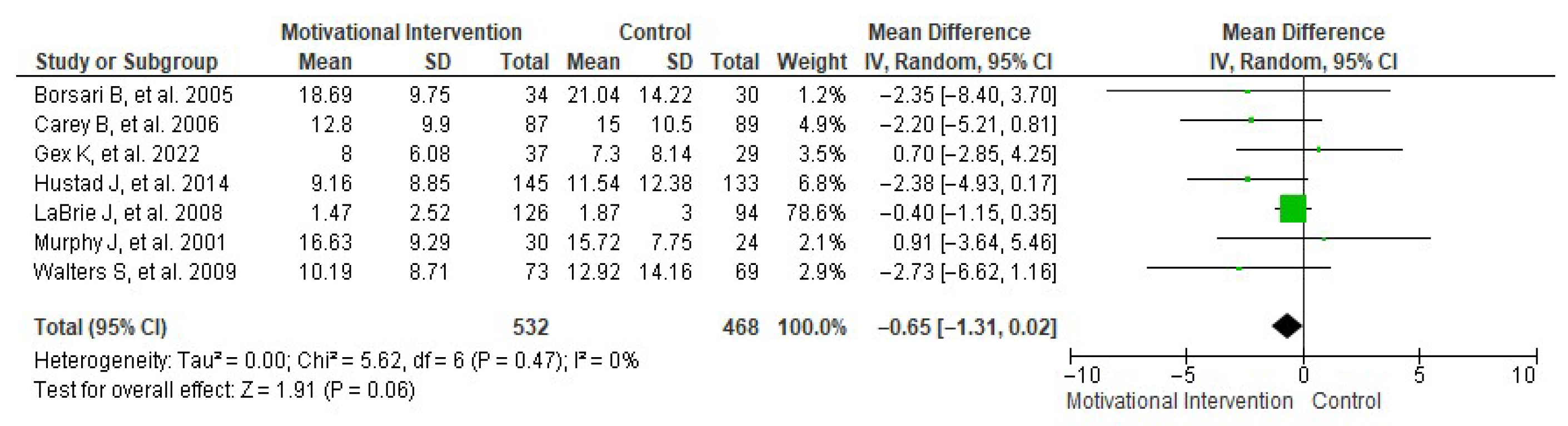

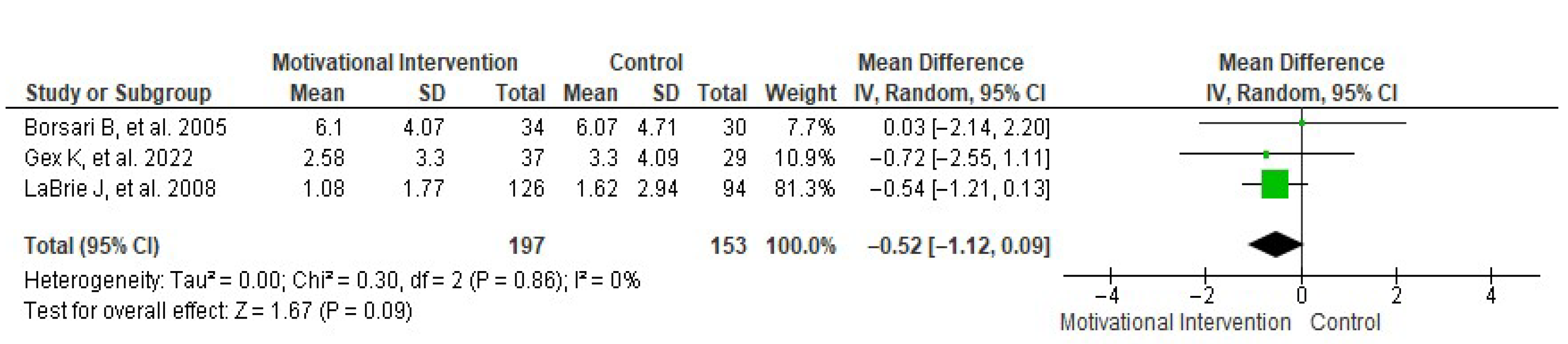

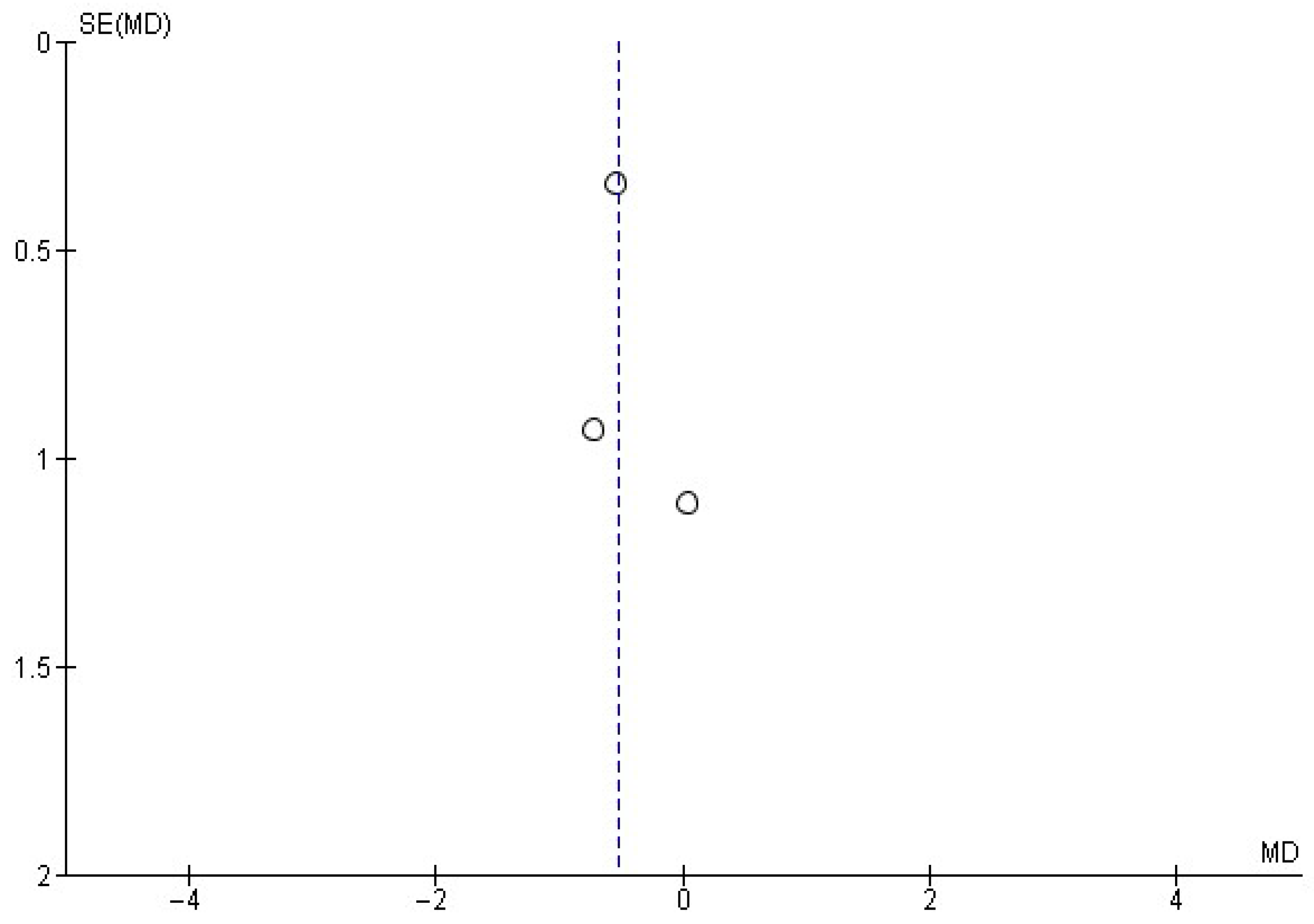

3.5. Alcohol Intoxication Episodes

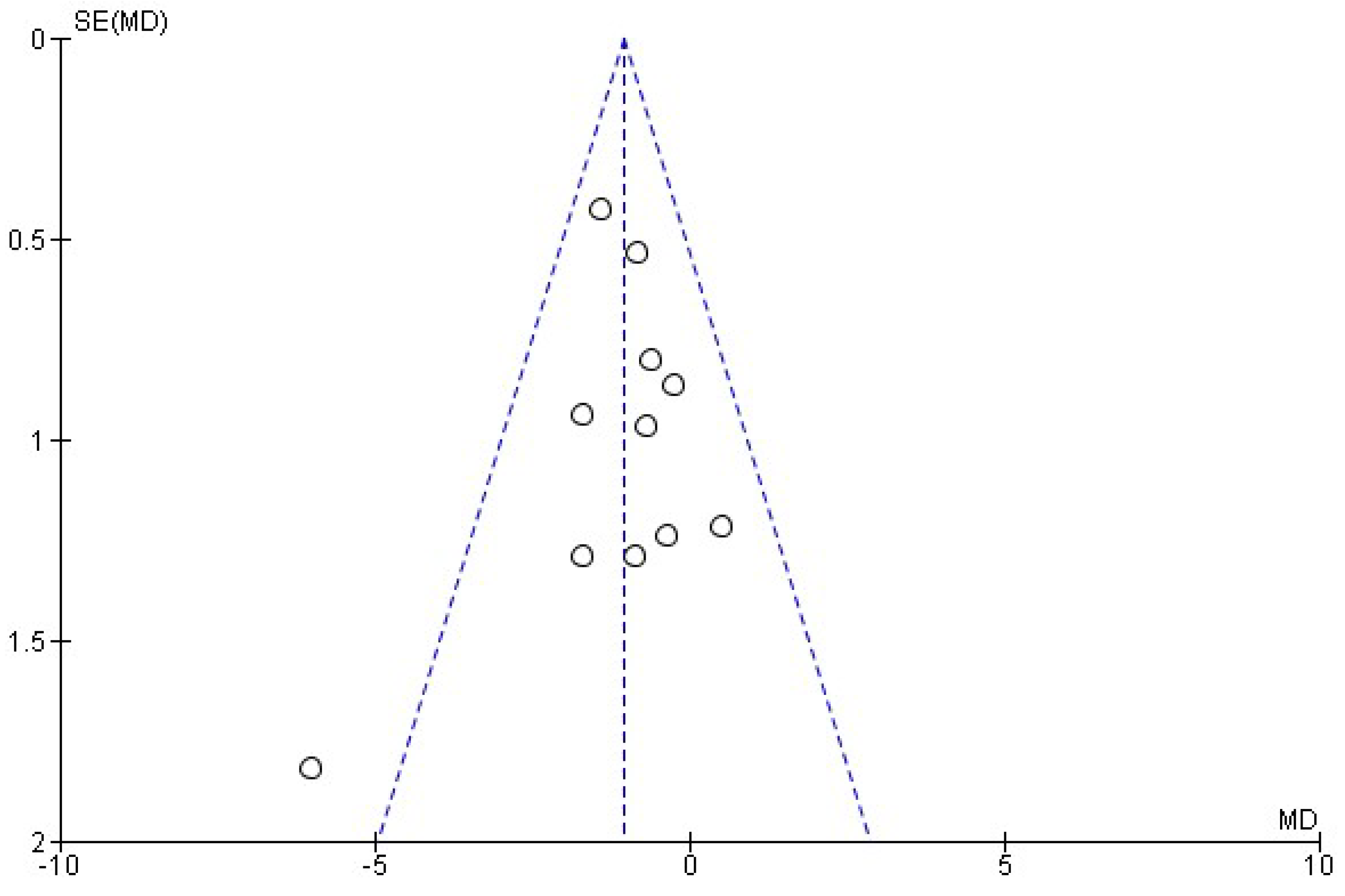

3.6. Consequences of Alcohol Consumption

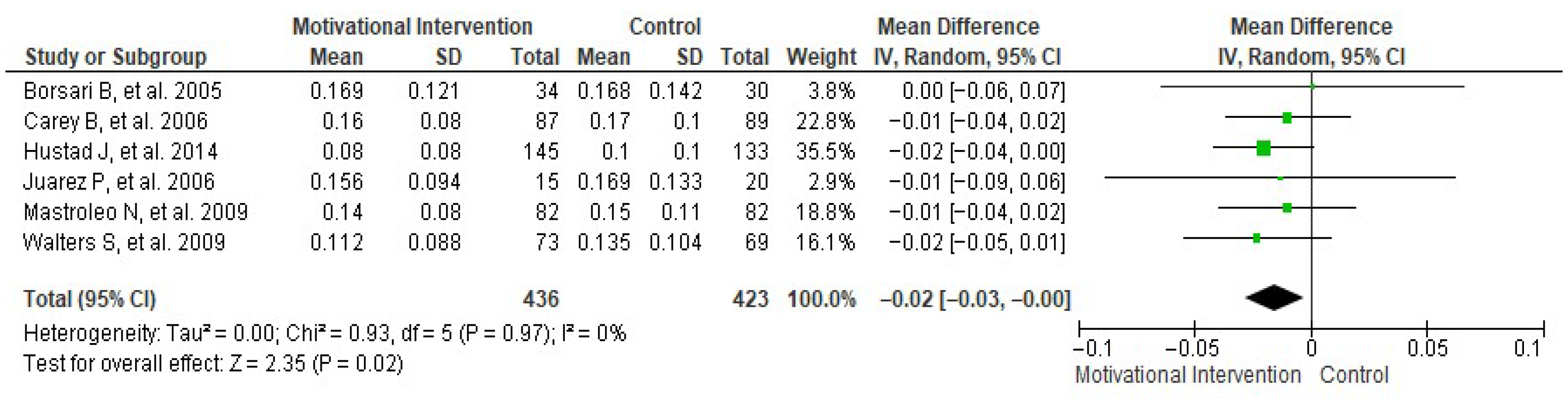

3.7. Blood Alcohol Concentration

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Ferrall-González, C.; González-Caballero, J.L.; Álvarez-Gálvez, J.; García-Carretero, M.Á.; Lagares-Franco, C. Patrones de consumo de alcohol en estudiantes universitarios mediante el análisis de clases latentes. Una revisión necesaria. Health Addict/Salud Drog. 2024, 24, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Estrategia Mundial Para Reducir el Uso Nocivo del Alcohol; OMS: Ginebra, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bulfone, G.; Ingravalle, F.; Scerbo, F.; Mazzotta, R.; Simonelli, I.; Pancaldi, A.; Ungaro, S.; Cocco, M.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R. Substance use and academic performance among university students: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, L.S. Consumo alcohólico en la población española. Adicciones 2002, 14, 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, L.D.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G.; Schulenberg, J.E. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2003. Vol. I: Secondary School Students; National Institute on Drug Abuse: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, H.; Lee, J.E.; Nelson, T.F.; Kuo, M. Underage college students’ drinking behavior, access to alcohol, and the influence of deterrence policies: Findings from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. J. Am. Coll. Health 2002, 50, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingson, R.W.; Heeren, T.; Zakocs, R.C.; Kopstein, A.; Wechsler, H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among US college students ages 18–24. J. Stud. Alcohol 2002, 63, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokinaro, S.; Vicente, J.; Benedetti, E.; Cerrai, S.; Colasante, E.; Arpa, S.; Chomynova, P.; Kraus, L.; Monshouwer, K.; Spilka, S.; et al. ESPAD Report 2019: Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Encuesta Sobre Alcohol y Drogas en Población General en España: EDADES 2011–2012; MSSSI: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez Garrido, J.M.; Azaustre Lorenzo, M.C. El Consumo de Alcohol en Universitarios. Estudio de las Relaciones Entre las Causas y los Efectos Negativos; Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, K.B.; Scott-Sheldon, L.A.; Elliott, J.C.; Bolles, J.R.; Carey, M.P. Computer-delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analysis. Addiction 2009, 104, 1807–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, E.; Kuntsche, S. Development and validation of the drinking motive questionnaire revised short form (DMQ–R SF). J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2009, 38, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, B.L.; Arkowitz, H.; Menchola, M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Wilbourne, P.L. Mesa Grande: A methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction 2002, 97, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaChance, H.; Feldstein Ewing, S.W.; Bryan, A.D.; Hutchison, K.E. What makes group MET work? A randomized controlled trial of college student drinkers in mandated alcohol diversion. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2009, 23, 598–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, K.D.; Curtin, L.; Kirkley, D.E.; Jones, D.L.; Harris, R. Group-based motivational interviewing for alcohol use among college students: An exploratory study. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2006, 37, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezquita, L.; Stewart, S.H.; Kuntsche, E.; Grant, V.V. Estudio transcultural del modelo de cinco factores de motivos de consumo de alcohol en universitarios españoles y canadienses. Adicciones 2016, 28, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrie, J.W.; Huchting, K.; Tawalbeh, S.; Pedersen, E.R.; Thompson, A.D.; Shelesky, K.; Larimer, M.; Neighbors, C. A randomized motivational enhancement prevention group reduces drinking and alcohol consequences in first-year college women. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008, 22, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, K.B.; Carey, M.P.; Maisto, S.A.; Henson, J.M. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hustad, J.T.P.; Mastroleo, N.R.; Kong, L.; Urwin, R.; Zeman, S.; LaSalle, L.; Borsari, B. The comparative effectiveness of individual and group brief motivational interventions for mandated college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014, 28, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogg, T.; Marshbanks, M.R.; Doherty, H.K.; Vo, P.T. Testing a brief motivational-interviewing educational commitment module for at-risk college drinkers: A randomized trial. Addict. Behav. 2019, 90, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzer, M.C.; Oddo, L.E.; Vasko, J.M.; Murphy, J.G.; Iwamoto, D.; Lejuez, C.W.; Chronis-Tuscano, A. Motivational interviewing plus behavioral activation for alcohol misuse in college students with ADHD. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2021, 35, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.T.; Vader, A.M.; Harris, T.R.; Field, C.A.; Jouriles, E.N. Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gex, K.S.; Mun, E.-Y.; Barnett, N.P.; McDevitt-Murphy, M.E.; Ruggiero, K.J.; Thurston, I.B.; Olin, C.C.; Voss, A.T.; Withers, A.J.; Murphy, J.G. A randomized pilot trial of a mobile delivered brief motivational interviewing and behavioral economic alcohol intervention for emerging adults. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2023, 37, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, S.W.; Forcehimes, A.A. Motivational interviewing with underage college drinkers: A preliminary look at the role of empathy and alliance. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 2007, 33, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsari, B.; Carey, K.B. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2005, 19, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Juarez, P.; Walters, S.T.; Daugherty, M.; Radi, C. A randomized trial of motivational interviewing and feedback with heavy drinking college students. J. Drug Educ. 2006, 36, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.G.; Duchnick, J.J.; Vuchinich, R.E.; Davison, J.W.; Karg, R.S.; Olson, A.M.; Smith, A.F.; Coffey, T.T. Relative efficacy of a brief motivational intervention for college student drinkers. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2001, 15, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastroleo, N.R.; Turrisi, R.; Carney, J.V.; Ray, A.E.; Larimer, M.E. Examination of posttraining supervision of peer counselors in a motivational enhancement intervention to reduce drinking in a sample of heavy-drinking college students. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2010, 39, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Marlatt, G.A.; Baer, J.S.; Kivlahan, D.R.; Dimeff, L.A.; Larimer, M.E.; Quigley, L.A.; Somers, J.M.; Williams, E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 66, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, J.E.; Tanner-Smith, E.E. Single-session alcohol interventions for heavy drinking college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs. 2015, 76, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Lipsey, M.W. Brief alcohol interventions for adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2015, 51, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.D.; Cushing, C.C.; Aylward, B.S.; Craig, J.T.; Sorell, D.M.; Steele, R.G. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxcroft, D.R.; Coombes, L.; Wood, S.; Allen, D.; Almeida Santimano, N.M.L.; Moreira, M.T. Motivational interviewing for the prevention of alcohol misuse in young adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 7, CD007025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, P.V.; Salomón, T.; Peltzer, R.I.; Cremonte, M.; Conde, K. The role of personalized normative feedback in the efficacy of brief intervention among Argentinian university students: A randomized controlled trial. Subst. Use Misuse 2024, 59, 1703–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Walters, S.T.; Tan, L.; Huh, D.; Zhou, Z.; Luningham, J.M.; Larimer, M.E.; Mun, E. Do brief motivational interventions increase motivation for change in drinking among college students? A two-step meta-analysis of individual participant data. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 47, 1433–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, K.B.; Scott-Sheldon, L.A.J.; Carey, M.P.; DeMartini, K.S. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addict. Behav. 2007, 32, 2469–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxcroft, D.R.; Moreira, M.T.; Almeida Santimano, N.M.L.; Smith, L.A. Social norms information for alcohol misuse in university and college students. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD006748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hingson, R.W.; Zha, W.; White, A.M. Drinking beyond the binge threshold: Predictors, consequences, and changes in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Goodman, K.M.; Seifert, T.A.; Tagliapietra-Nicoli, G.; Park, S.; Whitt, E.J. College student binge drinking and academic achievement: A longitudinal replication and extension. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2007, 48, 715–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Shu, J. Serious health consequences associated with alcohol use among college students: Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients seen in an emergency department. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2004, 65, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.K.; Calhoun, B.H.; Maggs, J.L. High-risk alcohol use behavior and daily academic effort among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.; Li, X.; McGue, M. The causal role of alcohol use in adolescent externalizing and internalizing problems: A Mendelian randomization study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2017, 41, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slutske, W.S. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college-attending peers. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Strategy | Filters Applied |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (motivational interview OR motivational interventions) AND (alcohol consumption OR alcohol drinking OR alcohol-related disorders) AND (university students OR college students) | Type of study: Randomized Controlled Trials |

| Scopus | ALL (“motivational interview”) OR ALL (“motivational intervention”) AND TITLE (“alcohol consumption”) OR TITLE (“alcohol drinking”) OR ALL (“alcohol-related disorders”) AND TITLE (“university students”) OR TITLE (“college students”) | Not applicable |

| BVS Library | (“motivational interview”) OR (“motivational intervention”) AND (“alcohol consumption”) OR (“alcohol drinking”) OR (“alcohol-related disorders”) AND (“university students”) OR (“college students”) | Type of study: Randomized Controlled Trials Language: English and Spanish |

| Authors, Year, Country | Population | Age of Participants | Type of Intervention | Follow-Up | Results | Conclusion | Risk of Bias |

| Feldstein S et al. [29] (2007) USA | 51 university students. 36 IG and 15 CG | 18–20 years | MI (IG, n = 36) and single assessment (CG, n = 15). | 2-month follow-up | Reduction in binge drinking episodes only in IG (t[34] = 2.08, p < 0.05). RAPI score decreased in both groups (IG: t[34] = 4.58, p < 0.001; CG: t[14] = 4.58, p < 0.001) | Motivational interviewing showed greater reductions in binge drinking episodes and alcohol-related problems | Low |

| Gex K et al. [28] (2022) USA | 66 university students. 37 IG and 29 CG | 18–25 years | MI + SFAS (IG, n = 37) and alcohol education (CG, n = 29). | 3-month follow-up | YAACQ score dropped from 8.30 ± 5.52 to 5.77 ± 5.59 (Cohen’s d = 0.46 [0.136–0.900]) in IG; in CG from 7.50 ± 4.51 to 4.80 ± 3.72 (Cohen’s d = 0.65) | A brief MI combined with SFAS is feasible and well tolerated by university students | Low |

| Juárez P et al. [31] (2006) USA | 89 university students. 68 IG and 21 CG | Mean age 19.43 years | MI (IG, n = 15), MI + in-person feedback (IG, n = 15), MI + online feedback (IG, n = 18), online feedback (IG, n = 20), single assessment (CG, n = 21). | 2-month follow-up | Daily drinks: MI from 1.29 ± 1.13 to 0.59 ± 0.52; MI + in-person feedback from 2.12 ± 1.36 to 1.20 ± 1.56; MI + online feedback from 1.42 ± 0.80 to 0.57 ± 0.50; online feedback from 1.77 ± 1.08 to 0.80 ± 0.64; CG from 1.57 ± 1.26 to 0.87 ± 0.69 | Reductions in alcohol consumption observed in participants receiving both types of feedback with MI | Some concerns |

| Carey B et al. [23] (2006) USA | 262 university students. 173 IG and 89 CG | 18–25 years | MI (IG, n = 87); enhanced MI with decisional balance module (IG, n = 86); single assessment (CG, n = 89). | 12-month follow-up | Daily drinks: MI from 5.7 ± 3.4 to 4.1 ± 2.5; enhanced MI from 5.8 ± 3.3 to 4.5 ± 2.2; CG from 5.8 ± 2.6 to 4.6 ± 2.5. Weekly binge episodes: MI from 7.6 ± 5.2 to 4.9 ± 3.5; enhanced MI from 7.0 ± 4.2 to 5.7 ± 4.2; CG from 7.7 ± 4.1 to 5.1 ± 4.0 | Alcohol consumption decreases with MI tailored for heavy-drinking university students | Some concerns |

| Walters S et al. [27] (2009) USA | 279 university students. 210 IG and 69 CG | Mean age 19.8 years | MI (IG, n = 70); MI + feedback (IG, n = 73); feedback (IG, n = 67); single assessment (CG, n = 69). | 6-month follow-up | Significant changes in weekly consumption at follow-up (t[275] = −2.11, p = 0.04). BAC levels decreased by 79% in IG | MI combined with feedback is effective in reducing alcohol consumption and related problems | Low |

| Mastroleo N et al. [33] (2010) USA | 238 university students. 156 IG and 82 CG | 18–20 years | BASICS-based motivational sessions. EAA (IG, n = 74); CPA (IG, n = 82); single assessment (CG, n = 82). | 3-month follow-up | Binge episode scores decreased significantly in BASICS groups: EAA from −0.58 ± 2.70 to −1.07 ± 3.08; CPA from 0.52 ± 2.99 to −0.58 ± 2.66; CG from −0.30 ± 3.34 to 0.05 ± 3.59 | BASICS-based MI was effective in reducing excessive alcohol consumption | Low |

| Hustad J et al. [24] (2014) USA | 178 university students. 145 IG and 133 CG | Mean age 19.08 years | Group MI (IG, n = 145); individual MI (CG, n = 133). | 6-month follow-up | YAACQ: group MI from 5.59 ± 4.94 to 3.30 ± 6.01; individual MI from 6.19 ± 5.41 to 3.84 ± 6.41. Weekly drinks: group MI from 5.59 ± 4.94 to 3.30 ± 6.01; individual MI from 6.19 ± 5.41 to 3.84 ± 6.41 | Both individual and group MI reduced alcohol consumption in university students | Some concerns |

| Meinzer M et al. [26] (2021) USA | 113 university students. 55 IG and 58 CG | Mean age 19.87 years | MI + behavioral activation (IG, n = 55); MI + supportive counseling (CG, n = 58). | 3-month follow-up | DDQ: IG from 16.10 to 10.94; CG from 13.75 to 8.63. YAACQ: IG from 7.02 to 5.92; CG from 5.42 to 4.78 | Adding behavioral activation to MI reduces alcohol-related consequences | Low |

| Murphy J et al. [32] (2001) USA | 39 university students. 27 IG and 12 CG | Mean age 19.6 years | BASICS (IG, n = 14); alcohol education (IG, n = 14); single assessment (CG, n = 12). | 9-month follow-up | Weekly drinking days: BASICS from 31.79 ± 11.57 to 21.36 ± 10.08; education from 27.75 ± 9.32 to 25.98 ± 14.38; CG from 29.25 ± 7.73 to 19.85 ± 6.69 | BASICS-based MI benefits excessive drinking reduction in university students | Some concerns |

| Marlatt G et al. [34] (1998) USA | 348 university students. 174 IG and 174 CG | 18–19 years | MI (IG, n = 174); single assessment (CG, n = 174). | 2-year follow-up | DDQ: IG from 4.7 ± 2.3 to 3.6 ± 2.5; CG from 4.2 ± 2.7 to 4.0 ± 2.8. ADS: IG from 7.9 ± 3.8 to 6.5 ± 3.5; CG from 8.2 ± 3.9 to 7.8 ± 4.5 | MI significantly reduces alcohol consumption in university students | Some concerns |

| Bogg T et al. [25] (2018) USA | 145 university students. 93 IG and 52 CG | Mean age 20.4 years | BASICS (IG, n = 44); BASICS + educational commitment (IG, n = 49); alcohol education (CG, n = 52). | 9-month follow-up | BDP drinking frequency: BASICS from 2.93 ± 1.21 to 1.87 ± 1.39; BASICS+educational commitment from 2.80 ± 1.08 to 2.08 ± 1.38; CG from 3.02 ± 1.42 to 2.50 ± 1.67 | BASICS-based MI is effective as a strategy to address alcohol consumption | Some concerns |

| Borsari B et al. [30] (2005) USA | 64 university students. 34 IG and 30 CG | Mean age 19.1 years | MI (IG, n = 34); alcohol education (CG, n = 30). | 6-month follow-up | Weekly drinks: MI from 19.22 ± 9.65 to 18.69 ± 9.75; CG from 20.95 ± 10.33 to 21.04 ± 14.22. RAPI: MI from 9.88 ± 7.81 to 5.00 ± 5.09; CG from 7.00 ± 4.84 to 6.71 ± 5.21 | Both groups reduced alcohol use, but MI showed greater benefits in reducing alcohol-related problems | Low |

| LaBrie J et al. [22] (2008) USA | 220 female university students. 126 IG and 94 CG | Mean age 18.1 years | Group MI (IG, n = 126); single assessment (CG, n = 94). | 10-week follow-up | Fewer binge drinking episodes in IG at follow-up (F[1, 202] = 8.75, p < 0.01). Alcohol-related consequences were also lower in IG (F[1, 193] = 3.90, p = 0.05) | MI participants showed lower alcohol use and consequences | Low |

| LaChance H et al. [17] (2009) USA | 206 university students. 148 IG and 58 CG | Mean age 18.6 years | Enhanced group MI (IG, n = 68); FAC education (IG, n = 80); alcohol education (CG, n = 58). | 6-month follow-up | Daily drinks: group MI from 5.98 ± 2.40 to 5.24 ± 1.81; FAC from 6.00 ± 2.25 to 5.95 ± 2.15; CG from 6.15 ± 2.37 to 6.40 ± 2.71 | MI showed greater benefits compared to other groups in reducing alcohol consumption | Low |

| Michael K et al. [18] (2006) USA | 91 university students. 47 IG and 44 CG | Mean age 18.5 years | MI (IG, n = 47); single assessment (CG, n = 44). | 45-day follow-up | Weekly drinking days in MI group remained at 5.3; CG from 5.9 to 5.8. Binge episodes: MI from 4.1 ± 5.2 to 2.7 ± 3.2; CG from 4.4 ± 5.1 to 4.2 ± 5.3 | MI could feasibly be incorporated into strategies to address alcohol consumption in university students | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serrano-Fernández, V.; Barroso-Corroto, E.; Rivera-Picón, C.; Molina-Gallego, B.; Quesado, A.; Carmona-Torres, J.M.; López-Soto, P.J.; Sánchez-Gil, A.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, P.M. Motivational Interventions for Reducing Excessive Alcohol Consumption Among University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192405

Serrano-Fernández V, Barroso-Corroto E, Rivera-Picón C, Molina-Gallego B, Quesado A, Carmona-Torres JM, López-Soto PJ, Sánchez-Gil A, Sánchez-González JL, Rodríguez-Muñoz PM. Motivational Interventions for Reducing Excessive Alcohol Consumption Among University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192405

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano-Fernández, Víctor, Esperanza Barroso-Corroto, Cristina Rivera-Picón, Brigida Molina-Gallego, Ana Quesado, Juan Manuel Carmona-Torres, Pablo Jesús López-Soto, Alba Sánchez-Gil, Juan Luis Sánchez-González, and Pedro Manuel Rodríguez-Muñoz. 2025. "Motivational Interventions for Reducing Excessive Alcohol Consumption Among University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192405

APA StyleSerrano-Fernández, V., Barroso-Corroto, E., Rivera-Picón, C., Molina-Gallego, B., Quesado, A., Carmona-Torres, J. M., López-Soto, P. J., Sánchez-Gil, A., Sánchez-González, J. L., & Rodríguez-Muñoz, P. M. (2025). Motivational Interventions for Reducing Excessive Alcohol Consumption Among University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 13(19), 2405. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192405