Why Organizational Commitment and Work Values of Veterans Home Caregivers Affect Retention Intentions: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

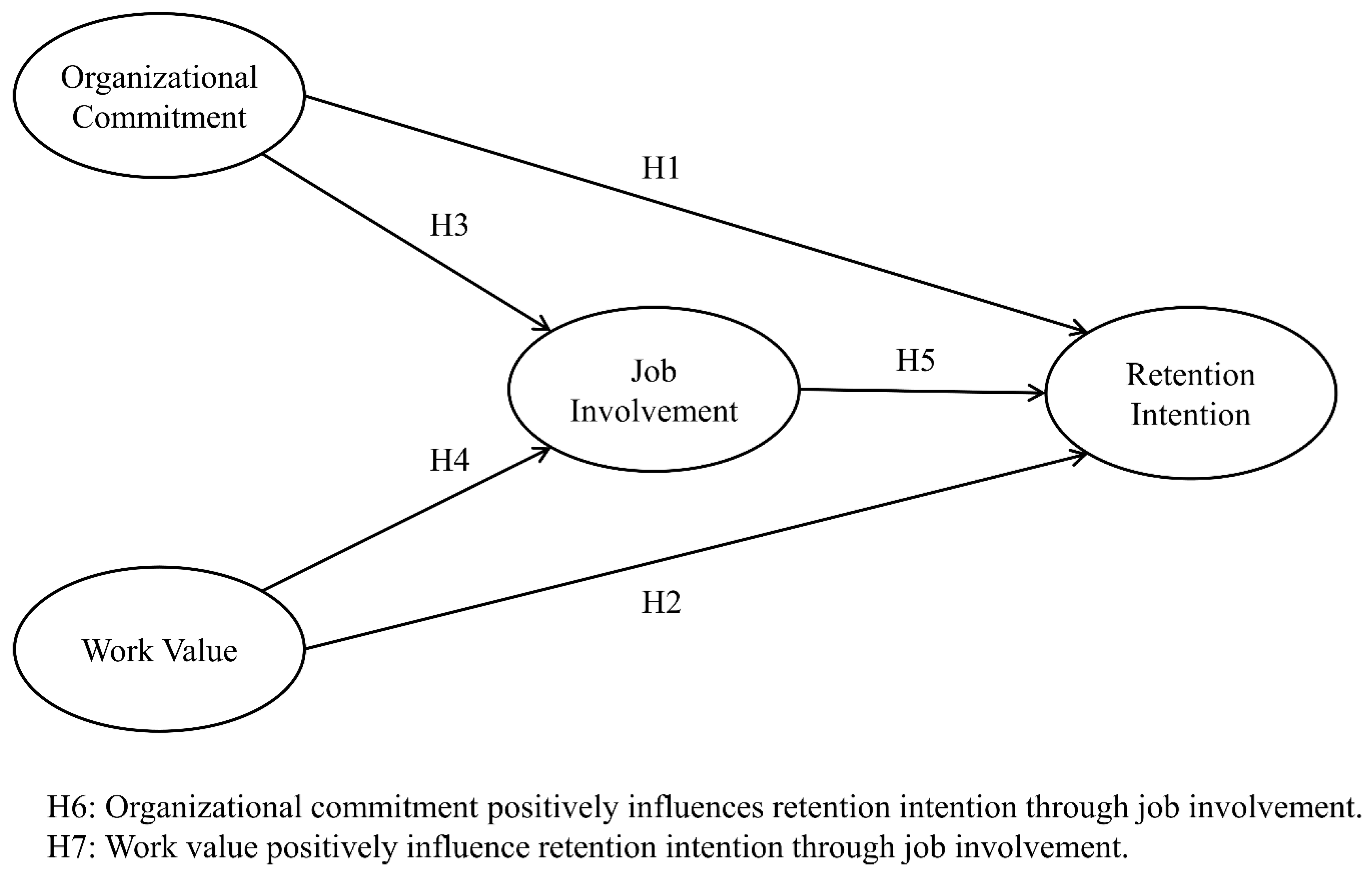

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Social Exchange Theory

2.2. Organizational Commitment

2.3. Work Value

2.4. Retention Intention

2.5. Job Involvement

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Ethical Considerations

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

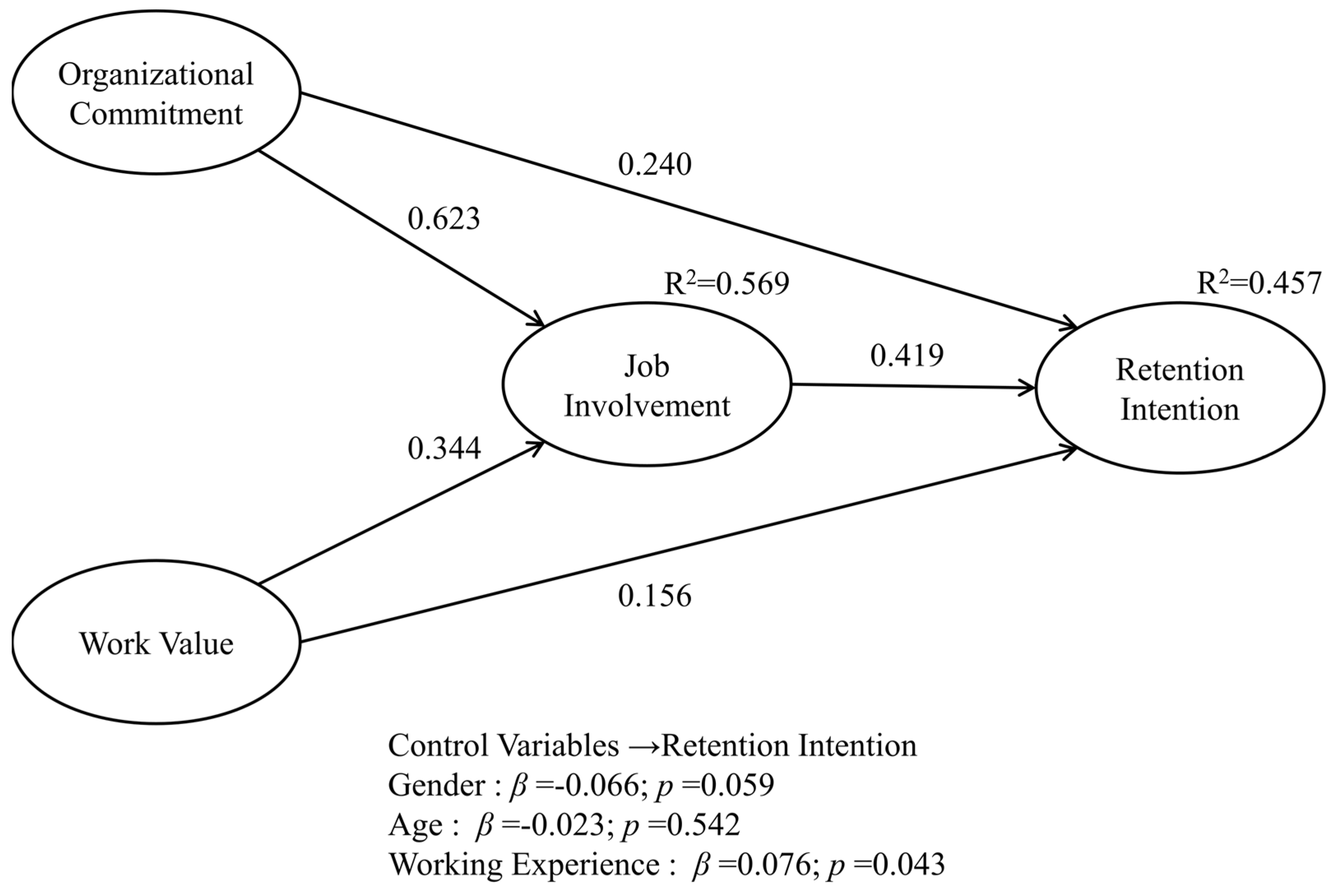

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. The Effects of Organizational Commitment on Job Involvement and Retention Intention

5.2. The Potential Meaning and Influence of Work Value Should Be Emphasized

5.3. The Core Mediating Role of Work Engagement in Retention Intention

5.4. Theoretical Implications

5.5. Practical Implications

5.6. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Organizational Commitment | [67] | |

| OC1 | I would like to pursue my career at the Veterans Home. | |

| OC2 | I view the problems of the Veterans Home as my own. | |

| OC3 | I feel like a member of a family at the Veterans Home. | |

| OC4 | The Veterans Home has provided me with significant support in my life. | |

| OC5 | I believe I have not yet made substantial contributions to the Veterans Home. (R) | |

| OC6 | The Veterans Home is deserving of my long-term loyalty. | |

| OC7 | I find it difficult to leave the Veterans Home because I worry about not being able to find a job elsewhere. | |

| OC8 | Leaving the Veterans Home would have negative consequences for me. | |

| OC9 | It is difficult to find a job that offers the same level of income stability as my current position at the Veterans Home. | |

| Work Value | [69] | |

| WV1 | The insurance system at the Veterans Home is good. | |

| WV2 | When I am sick, the Veterans Home takes good care of me. | |

| WV3 | My quality of life can be improved through my work at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV4 | I can realize my personal dreams through my work at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV6 | There are opportunities for further education and training at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV7 | I am proud of my work at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV8 | I am dedicated to my work at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV9 | I can properly arrange my schedule due to the flexibility of my work at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV10 | I strive for perfection in my work at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV11 | There are many opportunities for promotion at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV12 | My income at the Veterans Home is higher than that of others in similar positions. | |

| WV13 | Even without additional pay, I am willing to work overtime at night to complete my tasks at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV14 | I often arrive at work early to prepare for my duties at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV15 | I never feel confused or afraid while working at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV16 | I can receive appropriate raises or bonuses at the Veterans Home. | |

| WV17 | The welfare system at the Veterans Home is good. | |

| Job Involvement | [57] | |

| JI1 | The most important things that happen to me involve my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| JI2 | To me, my job at the Veterans Home is only a small part of who I am. (R) | |

| JI3 | I am very much personally involved in my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| JI4 | I live, eat, and breathe my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| JI5 | Most of my interests are centered around my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| JI6 | I have very strong ties with my job at the Veterans Home, which would be very difficult to break. | |

| JI7 | Usually, I feel detached from my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| JI8 | Most of my personal life goals are related to my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| JI9 | I consider my job at the Veterans Home to be very central to my existence. | |

| JI10 | I like to be absorbed in my job at the Veterans Home most of the time. | |

| Retention Intention | [71] | |

| RI1 | I hardly ever think about quitting my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| RI2 | I believe it is the right decision to continue working at the Veterans Home. | |

| RI3 | Even if there were a better opportunity, I would not consider quitting my job at the Veterans Home. | |

| RI4 | I feel obligated to continue working at the Veterans Home. | |

| RI5 | I would feel guilty if I were to leave the Veterans Home. | |

| RI6 | I do not want to leave the Veterans Home no matter how much it changes. | |

| RI7 | I am very loyal to the Veterans Home. | |

References

- Veterans Affairs Council. Monthly Bulletin of Veterans Statistics (No. 797). Available online: https://statvacrsweb.vac.gov.tw/webMain.aspx?k=defjsp1 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Changhua Veterans Home. Changhua Veterans Home Healthcare Unit Medical and Nursing Services Introduction. Available online: https://www.vac.gov.tw/cp-558-9985-207.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Omolara, J.; Ochieng, J. Occupational health and safety challenges faced by caregivers and the respective interventions to improve their wellbeing. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2024, 9, 3225–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, S. Millennials Aren’t Afraid to Change Jobs, and Here’s Why. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/sarahlandrum/2017/11/10/millennials-arent-afraid-to-change-jobs-and-heres-why/ (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Zeytinoglu, I.U.; Keser, A.; Yılmaz, G.; Inelmen, K.; Özsoy, A.; Uygur, D. Security in a sea of insecurity: Job security and intention to stay among service sector employees in Turkey. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2809–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Lin, Q.; Yang, T.; Shi, L.; Bao, X.; Wang, D. Distributive justice and turnover intention among medical staff in Shenzhen, China: The mediating effects of organizational commitment and work engagement. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2022, 15, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, R.; Sparrow, P.; Hernández-Lechuga, G. The effect of protean careers on talent retention: Examining the relationship between protean career orientation, organizational commitment, job satisfaction and intention to quit for talented workers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 2046–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmy, A.; Perkasa, D.H.; Haryadi, A.; Priyono, A. The roles of competence and job satisfaction on sales insurance performance: Organizational commitment as mediating variable. Qual.-Access Success 2025, 26, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.; Oh, J.; Park, J.; Kim, W. The relationship between work engagement and work–life balance in organizations: A review of the empirical research. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valéau, P.; Paille, P.; Dubrulle, C.; Guenin, H. The mediating effects of professional and organizational commitment on the relationship between HRM practices and professional employees’ intention to stay. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 1828–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Martek, I.; Chen, D. The formation mechanism of employees’ turnover intention in AEC industry. Buildings 2025, 15, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.S.; Posch, A.; Köllen, T.; Kraiczy, N.; Thom, N. Do “one-size” employment policies fit all young workers? Heterogeneity in work attribute preferences among the Millennial generation. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2024, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Forest, J.; Chen, Z. A dynamic computational model of employees’ goal transformation: Using self-determination theory. Motiv. Emot. 2019, 43, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Ma, Z.; Ma, Z.; Chen, B.; Cheng, S. Nurse practitioners’ work values and their conflict management approaches in a stressful workplace: A Taiwan study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Al-Sulaiti, K.; AlAbri, S.; Al-Sulaiti, I. Individual and psychological factors influencing hotel employees’ work engagement: The contingent role of self-efficacy. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2254914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.T.; Bentley, T.; Nguyen, D. Psychosocial work environment, work engagement, and employee commitment: A moderated, mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccoli, G.; Gastaldi, L.; Corso, M. The evolution of employee engagement: Towards a social and contextual construct for balancing individual performance and wellbeing dynamically. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaybani, S.; Noguchi-Watanabe, M.; Igarashi, A.; Saito, Y.; Yamamoto-Mitani, N. Factors related to intention to stay in the current workplace among long-term care nurses: A nationwide survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 80, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HakemZadeh, F.; Chowhan, J.; Neiterman, E.; Zeytinoglu, I.; Geraci, J.; Lobb, D. Differential relationships between work–life interface constructs and intention to stay in or leave the profession: Evidence from midwives in Canada. Psychol. Rep. 2024, 127, 1381–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullifor, D.P.; Petrenko, O.V.; Chandler, J.A.; Quade, M.J.; Rouba, Y. Employee reactions to perceived CSR: The influence of the ethical environment on OCB engagement and individual performance. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 161, 113835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, J.W.; Kelley, H.H. The Social Psychology of Groups; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.P.; Daly, T. Customer engagement and the relationship between involvement, engagement, self-brand connection and brand usage intent. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazanchi, S.; Masterson, S.S. Who and what is fair matters: A multi–foci social exchange model of creativity. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volery, T.; Tarabashkina, L. The impact of organisational support, employee creativity and work centrality on innovative work behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedkovski, V.; Guerci, M.; De Battisti, F.; Siletti, E. Organizational ethical climates and employee’s trust in colleagues, the supervisor, and the organization. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerstad, C.G.; Dysvik, A.; Kuvaas, B.; Buch, R. Negative and positive synergies: On employee development practices, motivational climate, and employee outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 1285–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieschollek, V.; Dlouhy, K. Employee referrals as counterproductive work behavior? Employees’ motives for poor referrals and the role of the cultural context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 2708–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, M.; Viswanathan, R.; Kaniyarkuzhi, B.K.; Neeliyadath, S. The moderating role of resonant leadership and workplace spirituality on the relationship between psychological distress and organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 855–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, R.; Sparrow, P.; Hernández-Lechuga, G. Proactive career orientation and physical mobility preference as predictors of important work attitudes: The moderating role of pay satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 1554–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.P.; Candela, L.L.; Carver, L. The structural relationships between organizational commitment, global job satisfaction, developmental experiences, work values, organizational support, and person–organization fit among nursing faculty. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumwesigye, G. The relationship between perceived organisational support and turnover intentions in a developing country: The mediating role of organisational commitment. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 942–952. [Google Scholar]

- Lages, C.R.; Piercy, N.F.; Malhotra, N.; Simões, C. Understanding the mechanisms of the relationship between shared values and service delivery performance of frontline employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 2737–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoux, G.; Guihur, I.; Leclerc, A. Co-operative difference and organizational commitment: The filter of socio-demographic variables. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 822–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.S.; Irving, P.G.; Taylor, S.F. A three-component model of customer commitment to service providers. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Marsden, P.V. Changing work values in the United States, 1973–2006. Soc. Sci. Res. 2013, 42, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ede, M.O.; Okeke, C.I.; Adene, F.; Areji, A.C. Perceptions of work value and ethical practices amongst primary school teachers, demographics, intervention, and impact. Psychol. Rep. 2023, 126, 380–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busque-Carrier, M.; Ratelle, C.F.; Le Corff, Y. Linking work values profiles to basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Psychol. Rep. 2022, 125, 3183–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Mor-Attias, R.; Vigoda-Gadot, E. Evolving motivation in public service: A three-phase longitudinal examination of public service motivation, work values, and academic studies among Israeli students. Public Adm. Rev. 2022, 82, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busque-Carrier, M.; Ratelle, C.F.; Le Corff, Y. Work values and job satisfaction: The mediating role of basic psychological needs at work. J. Career Dev. 2022, 49, 1386–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardre, P.L.; Reeve, J. Training corporate managers to adopt a more autonomy-supportive motivating style toward employees: An intervention study. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2009, 13, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortheix, F.M.; Dietrich, J.; Chow, A.; Salmela-Aro, K. The role of career values for work engagement during the transition to working life. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 83, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Hu, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Effect of work values on miners’ safety behavior: The mediating role of psychological empowerment and the moderating role of safety climate. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliman, J.; Gatling, A.; Kim, J.S. The effect of workplace spirituality on hospitality employee engagement, intention to stay, and service delivery. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 35, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, J.O.; Yean, T.E.; Adnan, Z.U.; Yahya, K.K.; Ahmad, M.N. Promoting employee intention to stay: Do human resource management practices matter. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2012, 6, 396–416. [Google Scholar]

- Oyetunde, M.O.; Ayeni, O.O. Exploring factors influencing recruitment and retention of nurses in Lagos State, Nigeria within year 2008 and 2012. Open J. Nurs. 2014, 4, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dawson, A.J.; Stasa, H.; Roche, M.A.; Homer, C.S.; Duffield, C. Nursing churn and turnover in Australian hospitals: Nurses’ perceptions and suggestions for supportive strategies. BMC Nurs. 2014, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bos-Nehles, A.; Meijerink, J. HRM implementation by multiple HRM actors: A social exchange perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 29, 3025–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Jones, G.R. The experience of work and turnover intentions: Interactive effects of value attainment, job satisfaction, and positive mood. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.C.; Perng, S.J.; Chang, F.M.; Lai, H.L. Influence of work values and personality traits on intent to stay among nurses at various types of hospital in Taiwan. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan Kassem, A.; Fekry Ahmed, M. Effect of work values and quality of work life on intention to stay among head nurses working at oncology center. Egypt. J. Health Care 2021, 12, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, U.A.; Gupta, M.; Cooke, F.L. Knowledge hide and seek: Role of ethical leadership, self-enhancement and job-involvement. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, R.N. Measurement of job and work involvement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matagi, L.; Baguma, P.; Baluku, M.M. Age, job involvement and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance among local government employees in Uganda. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2022, 9, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Choi, J.W. A study of job involvement prediction using machine learning technique. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2021, 29, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-refaei, A.A.A.; Ali, H.B.M.; Ateeq, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Alzoraiki, M.; Beshr, B. Unveiling the role of job involvement as a mediator in the linkage between academics’ job satisfaction and service quality. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2386463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescaux, E.; De Winne, S. (Not) seeing eye to eye on developmental HRM practices: Perceptual (in)congruence and employee outcomes. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 35, 1340–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, M.Q.; Decius, J.; Naveed, M.; Anwar, A. Transformational leadership promoting employees’ informal learning and job involvement: The moderating role of self-efficacy. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 43, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.H.; Chen, P.L. Optimism, social support, and caregiving burden among the long-term caregivers: The mediating effect of psychological resilience. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2024, 26, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulsenthilkumar, S.; Punitha, N. Mediating role of employee engagement: Job involvement, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Manag. Labour Stud. 2024, 49, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S. The role of self-efficacy in job satisfaction, organizational commitment, motivation and job involvement. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2020, 85, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoliarchuk, O.; Yang, Q.; Diedkov, M.; Serhieienkova, O.; Ishchuk, A.; Kokhanova, O.; Patlaichuk, O. Self-realization as a driver of sustainable social development: Balancing individual goals and collective values. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, W.C.; Holmes, M.R. Impacts of employee empowerment and organizational commitment on workforce sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.W.; Shen, P.F.; Hsu, Y.S. Effects of employees’ work values and organizational management on corporate performance for Chinese and Taiwanese construction enterprises. Sustainability 2015, 7, 16836–16848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. J. Appl. Psychol. 1975, 60, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Chen, M.H. Hospitality industry employees’ intention to stay in their job after the COVID-19 pandemic. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.T.; Chang, Y.L. The criterion-related validity of the financial personnel personality test by prove the relationship between personality, job performance, job satisfaction and willingness to stay: Take Bank P as an example. Cross-Strait Bank. Financ. 2015, 3, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanska-Farrington, S. Gender differences in the association between job characteristics, and work satisfaction and retention. Am. J. Bus. 2023, 38, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, K.Y.H.; Leung, C.T.L.; Chan, S.T.M. Satisfaction with organizational career management and the turnover intention of social workers in Guangdong Province, China. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2022, 48, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Brown, B.K. Method variance in organizational behavior and human resources research: Effects on correlations, path coefficients, and hypothesis testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1994, 57, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.K.; Kao, Y.T.; Lin, C.C. Common method variance in management research: Its nature, effects, detection, and remedies. J. Manag. 2006, 23, 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.G.; Taylor, A.B.; Wu, W. Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Aldabbas, H.; Pinnington, A.; Lahrech, A. The influence of perceived organizational support on employee creativity: The mediating role of work engagement. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 6501–6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki, M.; Morrison, V. Getting back or giving back: Understanding caregiver motivations and willingness to provide informal care. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 9, 636–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chompukum, P.; Vanichbuncha, T. Building a positive work environment: The role of psychological empowerment in engagement and intention to leave. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd-Banigan, M.; Sherman, S.R.; Lindquist, J.H.; Miller, K.E.; Tucker, M.; Smith, V.A.; Van Houtven, C.H. Family caregivers of veterans experience high levels of burden, distress, and financial strain. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2675–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagger, J.; Li, A. How does supervisory family support influence employees’ attitudes and behaviors? A social exchange perspective. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1123–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics (N = 477) | Category | Frequency (n = Responses) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 111 | 23.3 |

| Female | 366 | 76.7 | |

| Age | 21–30 years | 32 | 6.7 |

| 31–40 years | 30 | 6.3 | |

| 41–50 years | 97 | 20.3 | |

| 51–60 years | 151 | 31.7 | |

| Above 61 years | 167 | 35.0 | |

| Seniority | Within 6 months | 35 | 7.3 |

| 6 months to 1 year | 21 | 4.4 | |

| 1 year to 2 years | 64 | 13.4 | |

| 2 years to 5 years | 124 | 26.0 | |

| 5 years to 15 years | 169 | 35.4 | |

| 15 years to 20 years | 44 | 9.2 | |

| More than 20 years | 20 | 4.2 | |

| Education level | Junior high school or below | 133 | 27.9 |

| Senior/vocational high school | 229 | 48.0 | |

| College | 62 | 13.0 | |

| Graduate | 53 | 11.1 | |

| Marital status | Married | 255 | 53.5 |

| Divorced | 79 | 16.6 | |

| Widowed | 56 | 11.7 | |

| Unmarried | 87 | 18.2 | |

| Economic provider | Yes | 295 | 61.8 |

| No | 182 | 38.2 | |

| Household income | Below 28,000 NTD | 37 | 7.8 |

| 28,001 to 35,000 NTD | 232 | 48.6 | |

| 35,001 to 42,000 NTD | 113 | 23.7 | |

| 42,001 to 50,000 NTD | 36 | 7.5 | |

| Above 50,001 NTD | 59 | 12.4 | |

| n = 477 |

| Items | Unstd. | S.E. | t | p | Std. | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Commitment (OC) | 0.904 | 0.907 | 0.521 | |||||

| OC1 | 1 | 0.745 | ||||||

| OC2 | 0.732 | 0.053 | 13.750 | <0.001 | 0.635 | |||

| OC3 | 0.785 | 0.052 | 14.960 | <0.001 | 0.686 | |||

| OC4 | 0.714 | 0.051 | 13.984 | <0.001 | 0.645 | |||

| OC5 | 0.934 | 0.060 | 15.609 | <0.001 | 0.714 | |||

| OC6 | 1.314 | 0.075 | 17.446 | <0.001 | 0.790 | |||

| OC7 | 1.100 | 0.066 | 16.786 | <0.001 | 0.763 | |||

| OC8 | 1.144 | 0.075 | 15.284 | <0.001 | 0.700 | |||

| OC9 | 1.099 | 0.063 | 17.590 | <0.001 | 0.796 | |||

| Work Value (WV) | 0.950 | 0.951 | 0.552 | |||||

| WV1 | 1 | 0.673 | ||||||

| WV2 | 1.088 | 0.082 | 13.194 | <0.001 | 0.647 | |||

| WV3 | 1.084 | 0.076 | 14.318 | <0.001 | 0.708 | |||

| WV4 | 1.116 | 0.079 | 14.153 | <0.001 | 0.699 | |||

| WV6 | 1.153 | 0.079 | 14.600 | <0.001 | 0.723 | |||

| WV7 | 1.144 | 0.077 | 14.854 | <0.001 | 0.737 | |||

| WV8 | 1.195 | 0.076 | 15.810 | <0.001 | 0.791 | |||

| WV9 | 1.235 | 0.078 | 15.821 | <0.001 | 0.792 | |||

| WV10 | 1.168 | 0.073 | 15.927 | <0.001 | 0.798 | |||

| WV11 | 1.395 | 0.091 | 15.327 | <0.001 | 0.764 | |||

| WV12 | 1.259 | 0.083 | 15.134 | <0.001 | 0.753 | |||

| WV13 | 1.275 | 0.078 | 16.446 | <0.001 | 0.828 | |||

| WV14 | 1.279 | 0.081 | 15.756 | <0.001 | 0.788 | |||

| WV15 | 1.184 | 0.077 | 15.467 | <0.001 | 0.772 | |||

| WV16 | 1.328 | 0.093 | 14.285 | <0.001 | 0.706 | |||

| WV17 | 1.214 | 0.088 | 13.789 | <0.001 | 0.679 | |||

| Job Involvement (JI) | 0.911 | 0.913 | 0.513 | |||||

| JI1 | 1 | 0.706 | ||||||

| JI2 | 1.164 | 0.083 | 14.018 | <0.001 | 0.673 | |||

| JI3 | 1.596 | 0.102 | 15.633 | <0.001 | 0.752 | |||

| JI4 | 1.443 | 0.095 | 15.191 | <0.001 | 0.730 | |||

| JI5 | 1.215 | 0.086 | 14.145 | <0.001 | 0.679 | |||

| JI6 | 1.604 | 0.100 | 16.015 | <0.001 | 0.771 | |||

| JI7 | 1.752 | 0.110 | 15.935 | <0.001 | 0.767 | |||

| JI8 | 1.280 | 0.090 | 14.269 | <0.001 | 0.685 | |||

| JI9 | 1.124 | 0.076 | 14.813 | <0.001 | 0.712 | |||

| JI10 | 1.107 | 0.078 | 14.159 | <0.001 | 0.680 | |||

| Retention Intention (RI) | 0.926 | 0.928 | 0.650 | |||||

| RI1 | 1 | 0.801 | ||||||

| RI2 | 1.003 | 0.050 | 20.194 | <0.001 | 0.814 | |||

| RI3 | 1.131 | 0.062 | 18.369 | <0.001 | 0.758 | |||

| RI4 | 1.093 | 0.059 | 18.524 | <0.001 | 0.763 | |||

| RI5 | 0.980 | 0.047 | 20.752 | <0.001 | 0.830 | |||

| RI6 | 0.980 | 0.047 | 21.053 | <0.001 | 0.839 | |||

| RI7 | 1.150 | 0.055 | 20.858 | <0.001 | 0.833 | |||

| Constructs | Mean | SD | AVE | Discriminant Validity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | WV | JI | RI | ||||

| Organizational Commitment (OC) | 3.598 | 0.478 | 0.521 | 0.722 | 0.370 | 0.739 | 0.611 |

| Work Value (WV) | 4.338 | 0.497 | 0.552 | 0.333 | 0.743 | 0.585 | 0.484 |

| Job Involvement (JI) | 3.864 | 0.605 | 0.513 | 0.674 | 0.531 | 0.716 | 0.683 |

| Retention Intention (RI) | 4.051 | 0.700 | 0.650 | 0.566 | 0.450 | 0.631 | 0.806 |

| Path Analysis | Std. | Unstd. | S.E. | p | Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Variables | |||||

| Gender → Retention Intention | −0.066 | −0.101 | 0.054 | 0.059 | N |

| Age → Retention Intention | −0.023 | −0.011 | 0.018 | 0.542 | N |

| Working Experience → Retention Intention | 0.076 | 0.034 | 0.017 | 0.043 | Y |

| Hypothesis | |||||

| H1: Organizational Commitment → Retention Intention | 0.240 | 0.332 | 0.087 | <0.001 | Y |

| H2: Work Value → Retention Intention | 0.156 | 0.248 | 0.074 | <0.001 | Y |

| H3: Organizational Commitment → Job Involvement | 0.623 | 0.583 | 0.049 | <0.001 | Y |

| H4: Work Value → Job Involvement | 0.344 | 0.370 | 0.045 | <0.001 | Y |

| H5: Job Involvement → Retention Intention | 0.419 | 0.619 | 0.109 | <0.001 | Y |

| H6: Organizational Commitment → Job Involvement → Retention Intention | 0.261 | 0.361 | 0.087 | 0.001 | Y |

| H7: Work Value → Job Involvement → Retention Intention | 0.144 | 0.229 | 0.055 | <0.001 | Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeh, S.-H.; Huang, K.-C. Why Organizational Commitment and Work Values of Veterans Home Caregivers Affect Retention Intentions: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192396

Yeh S-H, Huang K-C. Why Organizational Commitment and Work Values of Veterans Home Caregivers Affect Retention Intentions: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192396

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeh, Szu-Han, and Kuo-Chung Huang. 2025. "Why Organizational Commitment and Work Values of Veterans Home Caregivers Affect Retention Intentions: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192396

APA StyleYeh, S.-H., & Huang, K.-C. (2025). Why Organizational Commitment and Work Values of Veterans Home Caregivers Affect Retention Intentions: A Social Exchange Theory Perspective. Healthcare, 13(19), 2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192396