Addressing Health Inequalities in Greece: A Comprehensive Framework for Socioeconomic Determinants of Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic Determinants and Health Outcomes in Comparative Perspective

3.2. Comparative Effect Sizes of Key Variables Predictive of Health Inequalities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EU | European Union |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| JAHEE | Joint Action Health Equity Europe |

| HIMS | Health Ine-quality Monitoring System |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| CHE | Current Health Expenditure |

References

- Stiglitz, J. The Euro: And Its Threat to the Future of Europe; Penguin: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler, D.; Basu, S. The Body Economic: Why Austerity Kills; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M. The Shifts and the Shocks: What We’ve Learned—And Have Still to Learn—From the Financial Crisis; Penguin: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nicole, S. Addressing Health Inequalities in the European Union—Concepts, Action, State of Play; European Economic and Social Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Commission of the Pan American Health Organization on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas. Just Societies: Health Equity and Dignified Lives. Report of the Commission of the Pan American Health Organization on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eikemo, T.A.; Bambra, C.; Huijts, T.; Fitzgerald, R. The first pan-European sociological health inequalities survey of the general population: The European Social Survey rotating module on the social determinants of health. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 33, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, G.; Whitehead, M.; World Health Organization. Levelling Up (Part 2): A Discussion Paper on European Strategies for Tackling Social Inequities in Health; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/107791 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Widuto, A. Regional Inequalities in the EU; European Parliamentary Research Service: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/637951/EPRS_BRI(2019)637951_EN.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- OECD. European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2020—State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-europe-2020_82129230-en.html (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Blümel, M.; Spranger, A.; Achstetter, K.; Maresso, A.; Busse, R. Germany: Health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 2020, 22, 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Child and Infant Mortality in England and Wales. 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/childhoodinfantandperinatalmortalityinenglandandwales/2019 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Health System Performance Measurement. 2025. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/access-data-and-reports/health-system-performance-measurement (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Högberg, P.; Henriksson, G.; Borrell, C.; Ciutan, M.; Costa, G.; Georgiou, I.; Halik, R.; Hoebel, J.; Kilpeläinen, K.; Kyprianou, T.; et al. Monitoring health inequalities in 12 European countries: Lessons learned from the joint action health equity Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s Health 2020 Data Insights. 2020. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/australias-health-2020-data-insights/summary (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2021: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/342703/9789240027053-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Papanastasiou, S.; Papatheodorou, C. The Greek depression: Poverty outcomes and welfare responses. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodorou, C.; Missos, V.; Papanastasiou, S. Social Impacts of the Crisis and Austerity Policies in Greece; Labour Institute, Observatory of Economic and Social Developments: Athens, Greece, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Petmesidou, M.; Papanastasiou, S.; Pempetzoglou, M.; Papatheodorou, C.; Polyzoidis, P. Health and Long-Term Care in Greece; Labour Institute, Observatory of Economic and Social Developments: Athens, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Papanastasiou, S. Income-related health inequalities under COVID-19 in Greece. e-Cadernos CES 2023, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petmesidou, M. Challenges to healthcare reform in crisis-hit Greece. e-Cadernos CES 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Universal Health Coverage (UHC). 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Eikemo, T.A.; Avrami, L.; Cavounidis, J.; Mouriki, A.; Gkiouleka, A.; McNamara, C.L.; Stathopoulou, T. Health in crises: Migration, austerity and inequalities in Greece and Europe—Introduction to the supplement. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Database. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/main/data/database (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Gross Domestic Product at Market Prices. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TEC00001 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Real GDP per Capita. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/SDG_08_10 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. At-Risk-of-Poverty Rate. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TESPM010 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat Expenditure on Social Protection as Percentage of GDP. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TPS00098 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Expenditure for Selected Health Care Providers by Health Care Financing Schemes. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/HLTH_SHA11_HPHF (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Out-of-Pocket Expenditure on Healthcare. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TEPSR_SP310 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Total Unemployment Rate. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TPS00203 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Employment and Activity by Sex and Age—Annual Data. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/LFSI_EMP_A (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Population by Educational Attainment Level, Sex, Age, Citizenship and Degree of Urbanisation (%). 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/EDAT_LFS_9916 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Life Expectancy at Birth by Sex. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TPS00205 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Healthy Life Years at Birth by Sex. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TPS00150 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Self-Perceived Health by Sex, Age and Degree of Urbanisation. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/HLTH_SILC_18 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. People Having a Long-Standing Illness or Health Problem, by Sex, Age and Income Quintile. 2025. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2908/HLTH_SILC_11 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Self-Perceived Long-Standing Limitations in Usual Activities Due to Health Problem by Sex, Age and Labour Status. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/HLTH_SILC_06 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Self-Reported Unmet Need for Medical Care by Sex. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/TESPM110 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Aytemiz, L.; Sart, G.; Bayar, Y.; Danilina, M.; Sezgin, F.H. The long-term effect of social, educational, and health expenditures on indicators of life expectancy: An empirical analysis for the OECD countries. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1497794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, A.; Hyder, S.; Mohamed Nor, N.; Younis, M. Government health expenditures and health outcome nexus: A study on OECD countries. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1123759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffia, P.; Bucciol, A.; Hashlamoun, S. Determinants of life expectancy at birth: A longitudinal study on OECD countries. Int. J. Health Econ. Manag. 2023, 23, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaba, E.; Balan, C.B.; Robu, I.B. The relationship between life expectancy at birth and health expenditures estimated by a cross-country and time-series analysis. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reche, E.; König, H.H.; Hajek, A. Income, self-rated health, and morbidity: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialani, C.; Mortazavi, R. The effect of objective income and perceived economic resources on self-rated health. Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Healthy, Prosperous Lives for All: The European Health Equity Status Report; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326879 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Bambra, C.; Eikemo, T.A. Welfare state regimes, unemployment and health: A comparative study of the relationship between unemployment and self-reported health in 23 European countries. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntaner, C.; Solar, O.; Vanroelen, C.; Martínez, J.M.; Vergara, M.; Santana, V.; Castedo, A.; Kim, I.-H.; Benach, J. Unemployment, informal work, precarious employment, child labor, slavery, and health inequalities: Pathways and mechanisms. Int. J. Health Serv. 2010, 40, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, M.; Ferrie, J.; Montgomery, S.M. Health and labour market disadvantage: Unemployment, non-employment, and job insecurity. In Social Determinants of Health; Marmot, M., Wilkinson, R.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 78–96. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, C.L.; Balaj, M.; Thomson, K.H.; Eikemo, T.A.; Solheim, E.F.; Bambra, C. The socioeconomic distribution of non-communicable diseases in Europe: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, F.; Matranga, D. Socioeconomic inequality in non-communicable diseases in Europe between 2004 and 2015: Evidence from the SHARE survey. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalstra, J.A.; Kunst, A.E.; Borrell, C.; Breeze, E.; Cambois, E.; Costa, G.; Geurts, J.; Lahelma, E.; Van Oyen, H.; Rasmussen, N.; et al. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: An overview of eight European countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von dem Knesebeck, O.; Vonneilich, N.; Lüdecke, D. Income and functional limitations among the aged in Europe: A trend analysis in 16 countries. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heyden, J.; Van Oyen, H.; Berger, N.; De Bacquer, D.; Van Herck, K. Activity limitations predict health care expenditures in the general population in Belgium. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Lippe, E.; Fehr, A.; Lange, C. Limitations to usual activities due to health problems in Germany. J. Health Monit. 2017, 2, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierrakos, G.; Goula, A.; Latsou, D. Predictors of unmet healthcare needs during economic and health crisis in Greece. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. Reducing Health Inequalities in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/96086 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Baeten, R.; Spasova, S.; Vanhercke, B.; Coster, S. Inequalities in access to healthcare: A study of national policies 2018. In European Social Policy Network (ESPN); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A.I. Older Europeans’ experience of unmet health care during the COVID-19 pandemic (first wave). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Indicators | Unit of Measure | Year | DOI | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic determinants | ||||

| Gross domestic product at market prices | Euro per capita | 2013–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TEC00001 | [25] |

| Real GDP per capita | Euro per capita | 2008–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/SDG_08_10 | [26] |

| At-risk-of-poverty rate | Percentage | 2013–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TESPM010 | [27] |

| Expenditure on social protection | Percentage GDP | 2011–2022 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TPS00098 | [28] |

| Government schemes and compulsory contributory healthcare financing schemes (public health expenditures) | Euro per capita | 2009–2022 | https://doi.org/10.2908/HLTH_SHA11_HPHF | [29] |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure on healthcare (private health expenditures) | Percentage share of total current health expenditure (CHE) | 2009–2022 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TEPSR_SP310 | [30] |

| Social determinants | ||||

| Unemployment rate | Percentage of population in the labor force | 2009–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TPS00203 | [31] |

| Employment rate | Percentage of total population | 2009–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/LFSI_EMP_A | [32] |

Population by educational attainment level:

| Percentage | 2008–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/EDAT_LFS_9916 | [33] |

| Health outcomes | ||||

| Life expectancy at birth | Year | 2012–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TPS00205 | [34] |

| Healthy life years at birth | Year | 2011–2022 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TPS00150 | [35] |

| Self-perceived health (Very good or good) | Percentage | 2008–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/HLTH_SILC_18 | [36] |

| People having a long-standing illness or health problem | Percentage | 2008–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/HLTH_SILC_11 | [37] |

| Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem (some or severe) | Percentage | 2008–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/HLTH_SILC_06 | [38] |

| Self-reported unmet need for medical care (too expensive or too far to travel or waiting list) | Percentage | 2008–2023 | https://doi.org/10.2908/TESPM110 | [39] |

| Unit of Measure | Reference Year | Eurostat’s Data * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita | € per capita | 2013–2023 | €16,240–€21,350 |

| real GDP per capita | € per capita | 2008–2023 | €21,420–€18,670 |

| At-risk-of-poverty rate | % of total population | 2013–2023 | 23.1–18.9% |

| Expenditure on social protection | % of GDP | 2011–2022 | 27.8–24.3% |

| Public health expenditures | € per capita | 2009–2022 | €1374–€1043 |

| Private health expenditures | % of total CHE | 2009–2022 | 29.50–33.54% |

| Unemployment rate | % of population in the labor force | 2009–2023 | 9.80–11.10% |

| Employment rate | % of total population | 2009–2023 | 65.40–67.40% |

| Less than primary, primary and lower secondary education | % of total population | 2008–2023 | 39.70–22.40% |

| Upper secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education | % of total population | 2008–2023 | 40.50–47.80% |

| Tertiary education | % of total population | 2008–2023 | 19.80–29.90% |

| Life expectancy at birth | year | 2012–2023 | 80.70–81.80 |

| Healthy life years at birth | year | 2011–2022 | 66.60–67.00 |

| Self-perceived health (Very good or good) | % of total population | 2008–2023 | 79.00–79.60% |

| People having a long-standing illness or health problem | % of total population | 2008–2023 | 22.10–24.40% |

| Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem (some or severe) | % of total population | 2008–2023 | 19.80–23.20% |

| Self-reported unmet need for medical care (too expensive or too far to travel or waiting list) | % of total population | 2008–2023 | 5.40–11.60% |

| Health Outcomes | Economic Determinants | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | Real GDP | Public Health Expenditures | Private Health Expenditures | Expenditure on Social Protection | At-Risk-of-Poverty Rate | ||

| Life expectancy at birth | r | −0.107 | −0.057 | −0.716 * | 0.525 | −0.220 | −0.064 |

| p value | 0.754 | 0.860 | 0.013 | 0.098 | 0.516 | 0.852 | |

| Healthy life years at birth | r | 0.744 * | 0.765 ** | 0.743 ** | −0.481 | −0.056 | −0.731 * |

| p value | 0.014 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.113 | 0.862 | 0.016 | |

| Self-perceived health | r | 0.474 | 0.215 | 0.191 | −0.202 | 0.123 | −0.864 ** |

| p value | 0.141 | 0.424 | 0.514 | 0.488 | 0.703 | 0.001 | |

| People having a long-standing illness or health problem | r | −0.706 * | −0.628 ** | −0.647 * | −0.610 * | −0.434 | −0.084 |

| p value | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.021 | 0.159 | 0.806 | |

| Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem | r | −0.630 * | −0.807 ** | −0.953 ** | 0.873 ** | −0.227 | 0.370 |

| p value | 0.038 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.479 | 0.262 | |

| Self-reported unmet need for medical care | r | 0.105 | −0.538 * | 0.742 ** | 0.730 ** | −0.418 | 0.510 |

| p value | 0.758 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.176 | 0.109 | |

| Health Outcome | Social Determinants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment Rate | Employment Rate | Primary Education (Level 0–2) | Secondary Education (Level 3–4) | Tertiary Education (Level 5–8) | ||

| Life expectancy at birth | r | 0.166 | −0.141 | 0.083 | −0.054 | −0.111 |

| p value | 0.605 | 0.661 | 0.797 | 0.868 | 0.731 | |

| Healthy life years at birth | r | −0.841 ** | 0.810 ** | −0.396 | 0.438 | 0.355 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.203 | 0.154 | 0.258 | |

| Self-perceived health | r | −0.653 ** | 0.642 ** | 0.566 * | 0.679 ** | 0.473 |

| p value | 0.008 | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.004 | 0.064 | |

| People having long-standing illness or health problem | r | 0.197 | −0.051 | −0.820 ** | 0.728 ** | 0.861 ** |

| p value | 0.481 | 0.856 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem | r | 0.602 * | −0.510 | −0.653 ** | 0.541 * | 0.712 ** |

| p value | 0.018 | 0.052 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.002 | |

| Self-reported unmet need for medical care | r | 0.512 | −0.369 | −0.365 | 0.260 | 0.425 |

| p value | 0.051 | 0.175 | 0.165 | 0.330 | 0.101 | |

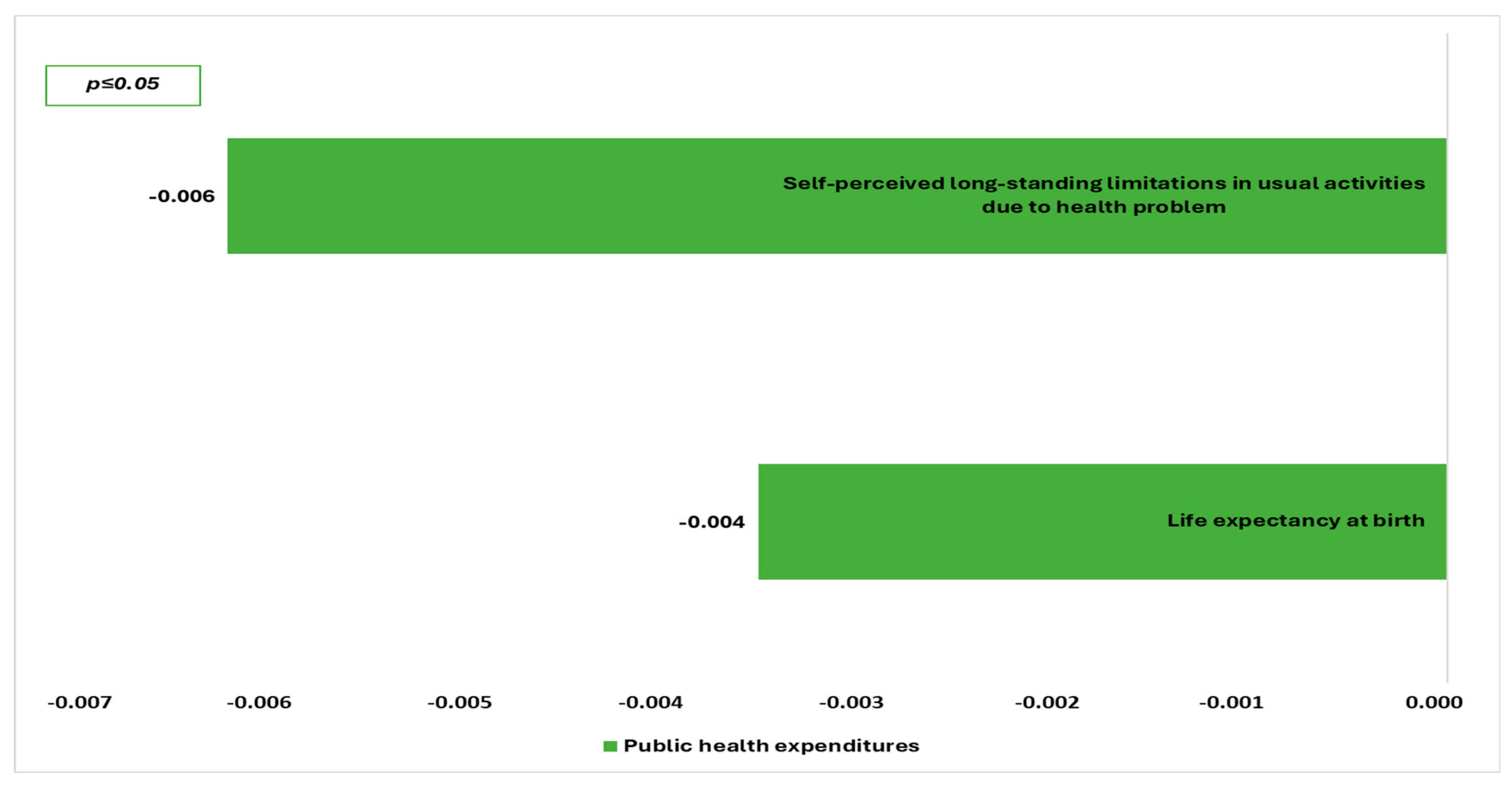

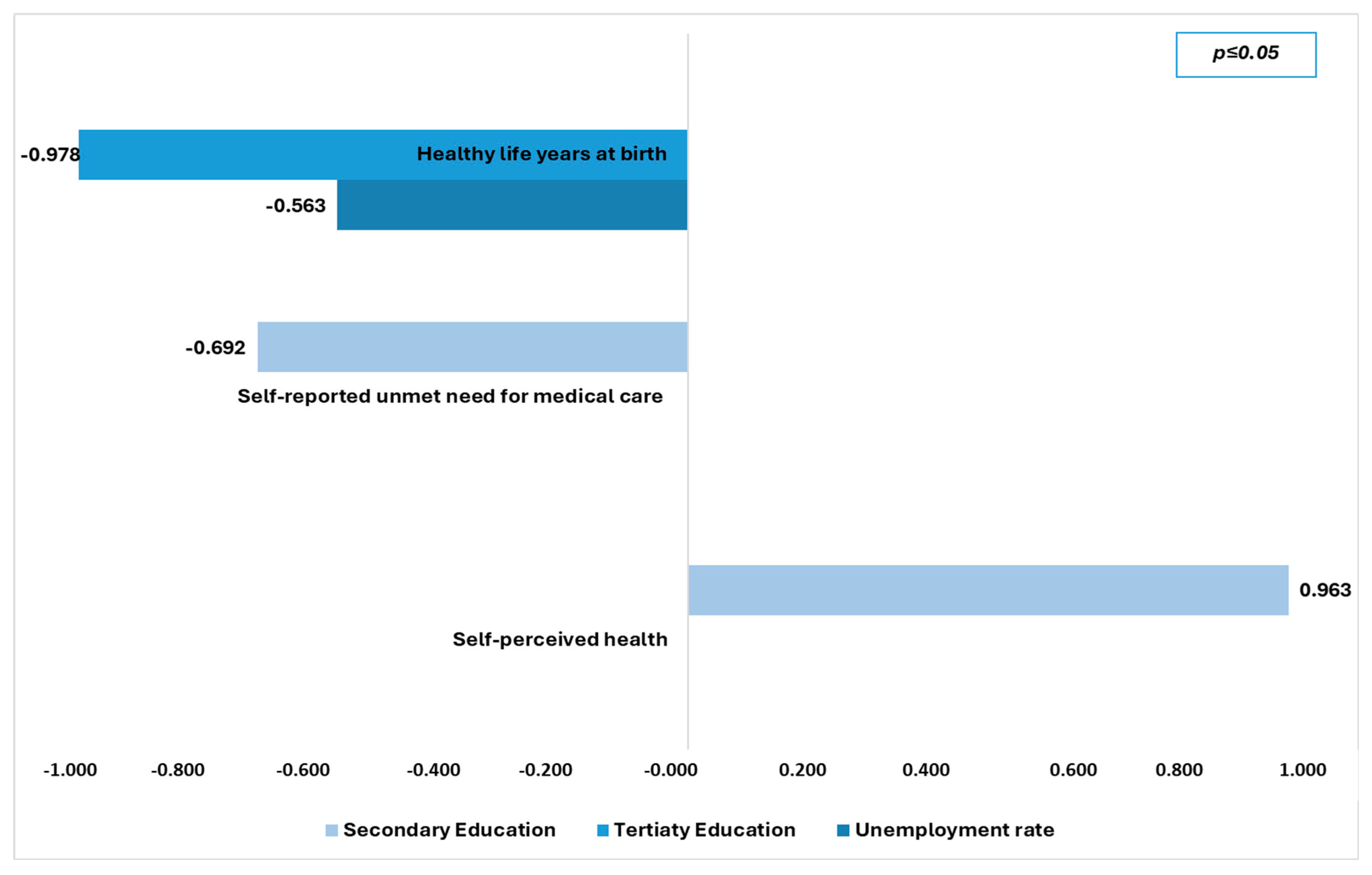

| Models | Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients | p Value | 95,0% Confidence Interval for B | Durbin Watson | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| 1 | Life expectancy at birth | (Constant) | 84.316 | 1.208 | 0.000 | 81.531 | 87.102 | 2.0.31 |

| Public health expenditures | −0.004 | 0.001 | 0.036 | −0.007 | 0.000 | |||

| 2 | Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problem | (Constant) | 29.153 | 1.589 | 0.000 | 25.489 | 32.817 | 1.811 |

| Public health expenditures | −0.006 | 0.002 | 0.010 | −0.010 | −0.002 | |||

| 3 | Self-perceived health | (Constant) | 33.194 | 7.467 | 0.002 | 15.976 | 50.412 | 1.382 |

| Secondary Education | 0.963 | 0.168 | 0.000 | 0.576 | 1.351 | |||

| 4 | Self-reported unmet need for medical care | (Constant) | 40.115 | 12.761 | 0.014 | 10.687 | 69.543 | 1.907 |

| Secondary Education | −0.692 | 0.287 | 0.043 | −1.354 | −0.029 | |||

| 5 | Healthy life years at birth | (Constant) | 103.566 | 12.504 | 0.000 | 74.000 | 133.133 | 2.209 |

| Unemployment rate | −0.0563 | 0.147 | 0.007 | −0.912 | −0.215 | |||

| Tertiaty Education | −0.978 | 0.348 | 0.026 | −1.801 | −0.156 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Triantafyllou, C.; Latsou, D.; Psiakis, V.; Pierrakos, G.; Breda, J. Addressing Health Inequalities in Greece: A Comprehensive Framework for Socioeconomic Determinants of Health. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192394

Triantafyllou C, Latsou D, Psiakis V, Pierrakos G, Breda J. Addressing Health Inequalities in Greece: A Comprehensive Framework for Socioeconomic Determinants of Health. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192394

Chicago/Turabian StyleTriantafyllou, Christos, Dimitra Latsou, Vion Psiakis, George Pierrakos, and Joao Breda. 2025. "Addressing Health Inequalities in Greece: A Comprehensive Framework for Socioeconomic Determinants of Health" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192394

APA StyleTriantafyllou, C., Latsou, D., Psiakis, V., Pierrakos, G., & Breda, J. (2025). Addressing Health Inequalities in Greece: A Comprehensive Framework for Socioeconomic Determinants of Health. Healthcare, 13(19), 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192394