Reproductive and Fertility Care of Women with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims

- (1)

- How do menstrual cycle phases impact clinical course in women with schizophrenia?

- (2)

- What are the important variables to recognize related to contraception and family planning in women with schizophrenia?

- (3)

- How effective and safe are fertility treatments for women with schizophrenia?

- (4)

- What are the clinical needs of women with schizophrenia during pregnancy and the postpartum period?

2. Methods

2.1. Screening and Selection of Evidence in Women with Schizophrenia

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Reporting of Results

3. Results

3.1. Menstrual Cycle in Women with Schizophrenia

3.2. Contraception and Family Planning in Women with Schizophrenia

3.3. Fertility Treatments in Women with Schizophrenia

3.3.1. Use of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Programs

3.3.2. Safety of Fertility Treatments

3.3.3. Effectiveness of Fertility Treatments

3.4. Pregnancy and Postpartum Health Needs in Women with Schizophrenia

3.4.1. Prevention and Treatment of Psychotic Disorder Relapse in Postpartum Women with Schizophrenia

3.4.2. Special Attention in the Perinatal Period

3.4.3. Support for the Mother-Infant Relationship

3.4.4. Reduction in Stigma

3.4.5. Economic, Occupational, and Vocational Help

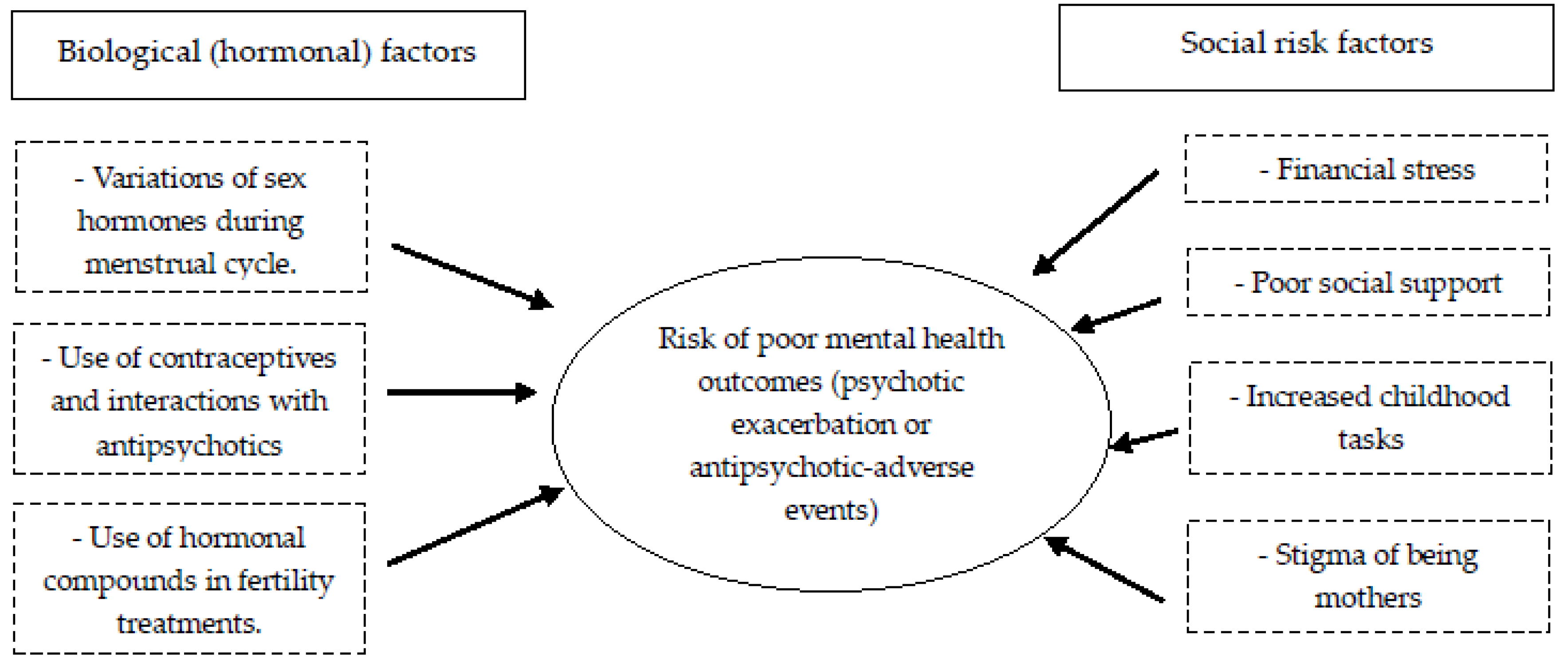

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Yi, Z. A glimpse of gender differences in schizophrenia. Gen. Psychiatry 2022, 35, e100823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, M.V. Sex/Gender differences in schizophrenia: Thinking back and thinking forward. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 316, 114738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, G.M.; Bucci, P.; Mucci, A.; Pezzella, P.; Galderisi, S. Gender differences in clinical and psychosocial features among persons with schizophrenia: A mini review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 789179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, M.V. Schizophrenia psychosis in women. Women 2021, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, A.; Monreal, J.A.; Seeman, M.V. The effect of menopause on antipsychotic response. Brain. Sci. 2022, 12, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrone, P.; Seeman, M.V.; Silvestri, S. Estrogen receptor activation and tardive dyskinesia. Can. J. Psychiatry 2000, 45, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riecher-Rössler, A.; Butler, S.; Kulkarni, J. Sex and gender differences in schizophrenic psychoses—A critical review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, B.A.; de Boer, J.N.; Sommer, I.E.C. Estrogens in schizophrenia: Progress, current challenges and opportunities. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, L.C.; Vigod, S.N. Sexual health of women with schizophrenia: A review. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 57, 100840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stilo, S.A.; Murray, R.M. Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jester, D.J.; Thomas, M.L.; Sturm, E.T.; Harvey, P.D.; Keshavan, M.; Davis, B.J.; Saxena, S.; Tampi, R.; Leutwyler, H.; Compton, M.T.; et al. Review of major social determinants of health in schizophrenia-spectrum psychotic disorders: I. Clinical outcomes. Schizophr. Bull. 2023, 49, 837–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergemann, N.; Parzer, P.; Runnebaum, B.; Resch, F.; Mundt, C. Estrogen, menstrual cycle phases, and psychopathology in women suffering from schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, P.; Mandal, N.; Sinha, V.K. Change of symptoms of schizophrenia across phases of menstrual cycle. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2020, 23, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lande, R.G.; Karamchandani, V. Chronic mental illness and the menstrual cycle. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2002, 102, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kirkbride, J.B.; Errazuriz, A.; Croudace, T.J.; Morgan, C.; Jackson, D.; Boydell, J.; Murray, R.M.; Jones, P.B. Incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in England, 1950–2009: A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7, e31660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, I.E.; Brand, B.A.; Gangadin, S.; Tanskanen, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Taipale, H. Women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders after menopause: A vulnerable group for relapse. Schizophr. Bull. 2023, 49, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, T.; Zhao, L.; Sun, Y.; Mao, Z.; Xing, Y.; Wang, C.; Bo, Q. Treatment of antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1337274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Liao, Y.; Kang, Z.; Feng, X.; Yue, W. Pharmacological treatment strategies for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Q.; Xing, X.; Li, T.; Mao, Z.; Zhou, F.; Wang, C. Menstrual dysfunction in women with schizophrenia during risperidone maintenance treatment. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinoff, A.N.; Silverblatt, N.S.; Vervaeke, H.E.; Horton, C.C.; Girma, E.; Kaye, A.D.; Kaye, A.; Kaye, J.S.; Garcia, A.J.; Neuchat, E.E.; et al. Hyperprolactinemia, Clinical Considerations, and Infertility in Women on Antipsychotic Medications. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2021, 51, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vigod, S.N.; Seeman, M.V.; Ray, J.G.; Anderson, G.M.; Dennis, C.L.; Grigoriadis, S.; Gruneir, A.; Kurdyak, P.A.; Rochon, P.A. Temporal trends in general and age-specific fertility rates among women with schizophrenia (1996–2009): A population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Schizophr. Res. 2012, 139, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kegnie Nigate, G.; Ayanaw Habitu, Y.; Chekol Tassew, W.; Ayale Ferede, Y.; Awoke Fentie, E. Contraceptive utilization and associated factors among reproductive age women attending psychiatric outpatient services, at northwest Amhara regional referral hospitals, Ethiopia. AJOG. Glob. Rep. 2025, 5, 100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E. The expression of sexuality in people with psychosis: Breaking the taboos. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 32, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoretsanitis, G.; Kane, J.M.; de Leon, J. Adding oral contraceptives to clozapine may require halving the clozapine dose: A new case and a literature review. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 40, 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoretsanitis, G.; Deligiannidis, K.M.; Paulzen, M.; Spina, E.; de Leon, J. Drug-drug interactions between psychotropic medications and oral contraceptives. Expert. Opin. Drug. Metab. Toxicol. 2022, 18, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhas, S.; Manchegowda, S.; Venkatasubramanian, G.; Kumar, V. Clozapine and Oral Contraceptives-Implications Beyond Pharmacokinetics: A Case Report. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayne, J.; Hauck, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Liira, H.; Morgan, V.A. Reproductive planning, vitamin knowledge and use, and lifestyle risks of women attending pregnancy care with a severe mental illness. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care. 2021, 39, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Brown, H.K.; Barker, L.C.; Dennis, C.L.; Vigod, S.N. Rapid repeat pregnancy in women with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 212, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Castagnini, E.; Langstone, A.; Mifsud, N.; Gao, C.; McGorry, P.; Killackey, E.; O’Donoghue, B. High-risk sexual behaviours in young people experiencing a first episode of psychosis. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 17, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegari, L.; Zhao, X.; Nelson, K.; Borrero, S. Contraception adherence among women Veterans with mental illness and substance use disorder. Contraception 2015, 91, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huybrechts, K.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Patorno, E.; Desai, R.J.; Mogun, H.; Dejene, S.Z.; Cohen, J.M.; Panchaud, A.; Cohen, L.; Bateman, B.T. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk of congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, L.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Bateman, B.; Wisner, K.L.; Gray, K.J.; Pennell, P.B.; Lester, B.; McDougle, C.J.; Suarez, E.A.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Association of antipsychotic drug exposure in pregnancy with risk of neurodevelopmental disorders: A national birth cohort study. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022, 182, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matevosyan, N. Pregnancy and postpartum specifics in women with schizophrenia: A meta-study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 283, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoila, L.; Isometsä, E.; Gissler, M.; Suvisaari, J.; Sailas, E.; Halmesmäki, E.; Lindberg, N. Pregnancy, delivery and postpartum in women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in Finland: A national register-based comparative study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 294, 113504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehghan, E.; Namiranian, N.; Ghadiri-Anari, A.; Kazem Razavi Ratki, S.; Azizi, R. Evaluation of hyperprolactinemia risk factors in infertile women referred to Yazd Infertility Center: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2022, 19, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.; Hageman, I.; Hougaard, C.Ø.; Sejbaek, C.S.; Assens, M.; Ebdrup, N.H.; Pinborg, A. Psychiatric disorders among women and men in assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment. The Danish National ART-Couple (DANAC) cohort: Protocol for a longitudinal, national register-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Hosseini, F.S.; Yunesian, M.; Keramat, A. Dropout of infertility treatments and related factors among infertile couples. Reprod. Health 2020, 17, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, R.; Okuhara, T.; Okada, H.; Goto, E.; Sakakibara, K.; Kiuchi, T. Association between stigma and anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among Japanese women undergoing infertility treatment. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Kuha, A.N.; Gissler, M.; Klemetti, R.; Luoto, R.; Koivisto, E.; Hemminki, E. Psychiatric disorders leading to hospitalization before and after infertility treatments. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 2018–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebdrup, N.H.; Assens, M.; Hougaard, C.O.; Pinborg, A.; Hageman, I.; Schmidt, L. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment in women with schizophrenia or related psychotic disorder: A national cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 177, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, R. A review of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions with antipsychotics. Ment. Health Clin. 2016, 6, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, S.S.M.; Müller, D.J.; Pouget, J.G. Pharmacogenetics of Antipsychotic Treatment in Schizophrenia. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2022, 2547, 389–425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravyn, D.; Ravyn, V.; Lowney, R.; Nasrallah, H.A. CYP450 pharmacogenetic treatment strategies for antipsychotics: A review of the evidence. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 149, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideras, K.; Ingle, J.N.; Ames, M.M.; Loprinzi, C.L.; Mrazek, D.P.; Black, J.L.; Weinshilboum, R.M.; Hawse, J.R.; Spelsberg, T.C.; Goetz, M.P. Coprescription of tamoxifen and medications that inhibit CYP2D6. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2768–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabi, H.; Karoui, M.; Ellou, F. Use of antipsychotics with tamoxifen. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64 (Suppl. S1), S432–S433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovar, C.; Kovar, L.; Rüdesheim, S.; Selzer, D.; Ganchev, B.; Kröner, P.; Igel, S.; Kerb, R.; Schaeffeler, E.; Mürdter, T.E.; et al. Prediction of Drug-Drug-Gene Interaction Scenarios of (E)-Clomiphene and Its Metabolites Using Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldur-Felskov, B.; Kjaer, S.K.; Albieri, V.; Steding-Jessen, M.; Kjaer, T.; Johansen, C.; Dalton, S.O.; Jensen, A. Psychiatric disorders in women with fertility problems: Results from a large Danish register-based cohort study. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, A.; Cobo, J.; Soria, V.; Usall, J.; Garcia-Rizo, C.; Bioque, M.; Monreal, J.A.; Labad, J. Women undergoing hormonal treatments for infertility: A systematic review on psychopathology and newly diagnosed mood and psychotic disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolman, C.; Jones, I.; Howard, L.M. Pre-conception to parenting: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature on motherhood for women with severe mental illness. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2013, 16, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Caneja, A.; Johnson, S. The views and experiences of severely mentally ill mothers. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004, 39, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.M.; Kumar, R.; Thornicroft, G. Psychosocial characteristics and needs of mothers with psychotic disorders. Br. J. Psychiatry 2001, 178, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.W.; Moulton, S.; Abel, K.M. The service needs of mothers with schizophrenia: A qualitative study of perinatal psychiatric and antenatal workers. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2008, 30, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeman, M.V. Intervention to prevent child custody loss in mothers with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 796763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, A.; Pouchon, A.; Bioulac, S.; Mallet, J.; Polosan, M.; Dondé, C. Management of schizophrenia in women during the perinatal period: A synthesis of international recommendations. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2022, 23, 1337–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, M.V. Grappling with issues of motherhood for women with schizophrenia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, I. Suicide and filicide in postpartum psychosis. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connellan, K.; Bartholomaeus, C.; Due, C.; Riggs, D.W. A systematic review of research on psychiatric mother-baby units. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, R.; Peters, S.; Wittkowski, A. Psychological interventions for managing postpartum psychosis: A qualitative analysis of women’s and family members’ experiences and preferences. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.W.; Warren, K.; Salmon, M.P.; Abel, K.M. Patterns of maternal responding in postpartum mothers with schizophrenia. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2008, 31, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada Correa, A.M.; Andrade Carrillo, R.A.; Suarez Vega, D.C.; Gómez Cano, S.; Agudelo Arango, L.G.; Tabares Builes, L.F.; Agudelo García, Á.M.; Uribe Villa, E.; Aguirre-Acevedo, D.C.; López-Jaramillo, C. Sexual and Reproductive Health in Patients with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 49, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, K.F.; Reilly, T.J.; Allan, S.; Golightly, E. The menstrual cycle: An overlooked vital sign in psychiatry? BMJ Ment. Health 2025, 28, e301463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukangabire, P.; Umuziga, M.P.; Umubyeyi, B.; Mukamana, D.; Gishoma, D.; Baziga, V.; Uwimana, P.; Sebera, F.; Bazirete, O.; Kanazayire, C. Family planning knowledge, use, and associated factors among women with mental illness and epilepsy in Rwanda: A cross-sectional study. Front. Glob. Women’s Health 2024, 5, 1373051. [Google Scholar]

- Tort-Nasarre, G.; Galbany-Estragués, P.; Saz Roy, M.Á.; Romeu-Labayen, M. Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Provided to Women Diagnosed with Serious Mental Illness: Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, A.K.; Determan, M.L.; Wright, J.A.; Matey, E.; Leung, J.G. The potential influence of estrogen-containing oral contraception on clozapine metabolism in a patient with known pharmacogenomic status. Ment. Health Clin. 2024, 14, 220–223. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.H.; Goh, K.K.; Chiu, Y.H.; Lin, C.H.; Chen, C.H.; Lane, H.Y.; Lu, M.L. Inverse dose-dependent effects of aripiprazole on sexual dysfunction and prolactin levels in patients with schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 184, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirim, D.; Bağcı, F.A. Dissecting the shared molecular mechanisms underlying polycystic ovary syndrome and schizophrenia etiology: A translational integrative approach. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2025, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safont, G.; Garriga, M.; González-Rodríguez, A.; Amoretti, S.; Simón, O.; Solè, E.; Garcia-Rizo, C.; Arranz, B.; Vieta, E.; Bernardo, M. Maternity in women with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud. Ment. 2025, 18, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESHRE PGT Consortium Steering Committee; Carvalho, F.; Coonen, E.; Goossens, V.; Kokkali, G.; Rubio, C.; Meijer-Hoogeveen, M.; Moutou, C.; Vermeulen, N.; De Rycke, M. ESHRE PGT Consortium good practice recommendations for the organisation of PGT. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2020, 2020, hoaa021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Njagi, P.; Groot, W.; Arsenijevic, J.; Dyer, S.; Mburu, G.; Kiarie, J. Financial costs of assisted reproductive technology for patients in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2023, 2023, hoad007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farland, L.V.; Khan, S.M.; Missmer, S.A.; Stern, D.; Lopez-Ridaura, R.; Chavarro, J.E.; Catzin-Kuhlmann, A.; Sanchez-Serrano, A.P.; Rice, M.S.; Lajous, M. Accessing medical care for infertility: A study of women in Mexico. F S Rep. 2022, 4, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddleston, A.; Ray, K.; Bacani, R.; Staggs, J.; Anderson, R.M.; Vassar, M. Inequities in medically assisted reproduction: A scoping review. Reprod. Sci. 2023, 30, 2373–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ombelet, W.; Lopes, F. Fertility care in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod. Fertil. 2024, 5, e240042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, L.M.; Wilson, C.A.; Reilly, T.J.; Moss, K.M.; Mishra, G.D.; Coupland-Smith, E.; Riecher-Rössler, A.; Seedat, S.; Smith, S.; Steinberg, J.R.; et al. Women’s reproductive mental health: Currently available evidence and future directions for research, clinical practice and health policy. World Psychiatry 2025, 24, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klatter, C.K.; van Ravesteyn, L.M.; Stekelenburg, J. Is collaborative care a key component for treating pregnant women with psychiatric symptoms (and additional psychosocial problems)? A systematic review. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2022, 25, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.K.N.; Lee, K.C.K.; Correll, C.U.; So, Y.K.; Chan, C.Y.; Wong, C.S.M.; Cheung, K.W.; Seto, M.T.; Lin, J.; Chang, W.C. Adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes associated with maternal schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and prenatal antipsychotic use: A meta-analysis of 37,214,330 pregnancy deliveries and propensity-score weighted population-based cohort study assessing confounder dependency of risk estimates. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 954–967. [Google Scholar]

- González-Rodríguez, A.; Seeman, M.V.; Natividad, M.; Barrio, P.; Román, E.; Balagué, A.; Paolini, J.P.; Monreal, J.A. Review of male and female care needs in schizophrenia: A new specialized clinical unit for women. Women 2023, 3, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antipsychotic-Related Concerns at the Pregnancy Planning Stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patient concern | Recommendations | |

| Desire for contraception | Estrogen levels impact antipsychotic plasma concentrations [24,25,26]. | Therapeutic drug monitoring. |

| Planning to conceive | Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia reduces fertility [17,18,20]. | Avoid prolactin-raising antipsychotics. |

| Contraceptive efficacy | ||

| Patient concern | Recommendations | |

| Desire for contraception | Women with schizophrenia show high rates of unplanned pregnancies [29,30]. | Use of long-acting reversible contraceptives or an Intrauterine Device (IUD). |

| Pharmacotherapy during pregnancy | ||

| Patient concern | Recommendations | |

| Planning to conceive | The perinatal period is an important time to prevent relapse for the health of both the woman and the offspring [33]. | Discuss the risks and benefits of treatment options for the mother and her fetus. For many pregnant women, continuation of an antipsychotic medication is imperative for her health and her family. |

| Patient Concern | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| Use of fertility treatments | Few women with schizophrenia are included in fertility treatments [37,38,39]. | To identify and address barriers to accessing fertility treatment for women with schizophrenia. |

| Safety of fertility treatments | There are potential interactions between antipsychotics and medications used in ART [47]. | Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions between ART treatments and psychotropic medications should be considered [41]. |

| Effectiveness of fertility treatments | Lower treatment success in women with psychotic disorders than in controls [40]. Hyperprolactinemia reduces the effectiveness of fertility treatments [49]. | Optimizing healthy lifestyle habits, treating hyperprolactinemia, and providing close follow-up may help to improve fertility rates in people with schizophrenia [49]. |

| Patient Concern | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention of worsening clinical course | Insomnia, poor hygiene, and suspiciousness are associated with poor mental health [54] | Maintenance of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions [53] |

| Clinical attention perinatal period | Psychological interventions can be held to promote trust and improve adherence to follow-up [59] | Development of well-trained multidisciplinary teams [55] |

| Support for the mother and children | Family visits, psychoeducation, and training can improve the health of both mothers and babies [58]. | Offering parenting assessment and additional support services to perinatal women with schizophrenia [51,56] |

| Anti-stigma interventions | The stigma of being a mother or caring for children impacts clinical outcomes in schizophrenia [50] | Provide health and legal guidance to mothers to support childcare tasks [50] |

| Socioeconomic needs | Financial stress impacts caring for children [56]. | Help with financial resources may help women caring for children [56]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Rodríguez, A.; Monreal, J.A.; Natividad, M.; Cobo, J.; Palacios-Hernández, B.; Susser, L.C. Reproductive and Fertility Care of Women with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2349. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182349

González-Rodríguez A, Monreal JA, Natividad M, Cobo J, Palacios-Hernández B, Susser LC. Reproductive and Fertility Care of Women with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2349. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182349

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Rodríguez, Alexandre, José Antonio Monreal, Mentxu Natividad, Jesús Cobo, Bruma Palacios-Hernández, and Leah C. Susser. 2025. "Reproductive and Fertility Care of Women with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2349. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182349

APA StyleGonzález-Rodríguez, A., Monreal, J. A., Natividad, M., Cobo, J., Palacios-Hernández, B., & Susser, L. C. (2025). Reproductive and Fertility Care of Women with Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. Healthcare, 13(18), 2349. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182349