Patterns of Prescription Switching in a Uniform-Pricing System for Multi-Source Drugs: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

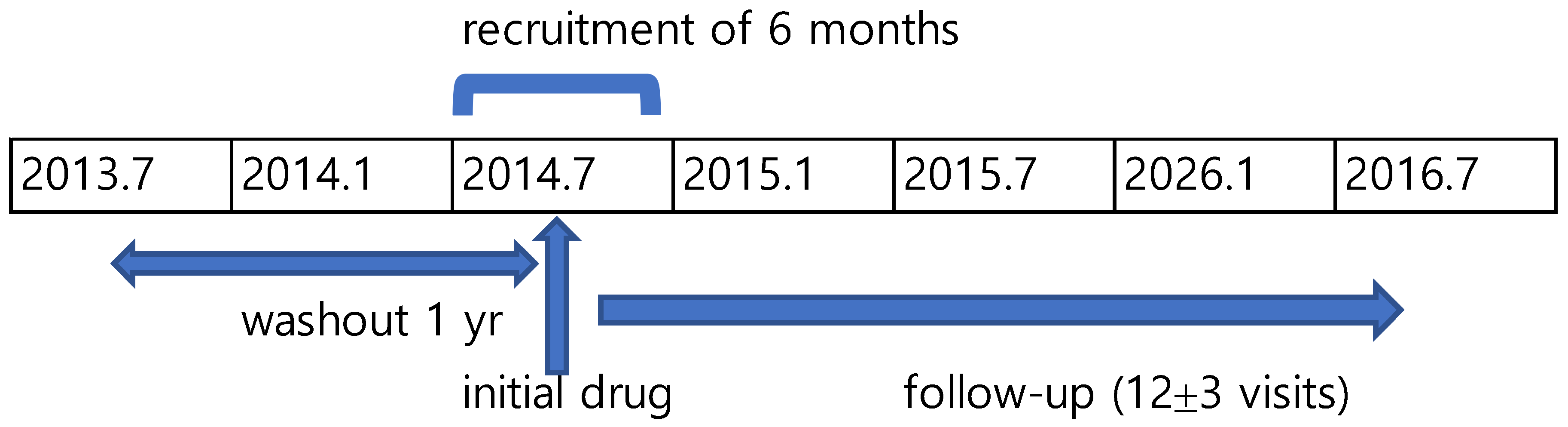

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population and Unit of Analysis

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Independent Variables

2.4.1. Number of Sources

2.4.2. Types of Physician Practice

2.4.3. Insurance Type

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Results

2.6.1. Description of Studied Drug Therapy Courses

2.6.2. Multi-Source Prescription Switching (MSPS) and Its Variation

3. Sources of MSPS Variation

3.1. Drug Characteristics

3.2. Physician Practice Setting and Geographic Region

3.3. Patient Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Context

4.2. Policy Implications

4.3. Key Policy Considerations:

- Promote INN-based prescribing in institutional settings through formulary alignment and clinical governance (e.g., P&T committees).

- Enhance physician education on bioequivalence and prescribing standards in independent practice settings.

- Explore pilot programs for prescribing audits and transparency mechanisms (e.g., reporting of switching patterns or financial disclosures).

- Consider centralized procurement or formulary standardization strategies, drawing on international models (e.g., UK, Sweden, Australia).

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSPS | Multi-Source Prescription Switch |

| POP | Point of Prescription |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| DAW | Dispense As Written |

| INN | International Non-proprietary Names |

| NHIS | Korean National Health Insurance Services |

| HIRA | Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment |

| HCTZ | Hydrochlorothiazide |

| P&T | Pharmacy and Therapeutics |

References

- Choi, E. The number of generic substitutes exceeded the first one million. Daily Pharm Korea, 13 March 2018. Available online: https://www.dailypharm.com/Users/News/NewsView.html?ID=237570 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Cho, M.H.; Yoo, K.B.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, K.S.; Kwon, J.A.; Han, K.T.; Kim, J.H.; Park, E.C. The effect of new drug pricing systems and new reimbursement guidelines on pharmaceutical expenditures and prescribing behavior among hypertensive patients in Korea. Health Policy 2015, 119, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.; Chae, S.M.; Kim, N.S.; Park, S. Effects of pharmaceutical cost containment policies on doctors’ prescribing behavior: Focus on antibiotics. Health Policy 2015, 119, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M.; Kim, J. Perception and attitude of Korean physicians towards generic drugs. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celtikci, P.; Ergun, O.; Durmaz, H.A.; Conkbayir, I.; Hekimoglu, B. Evaluation of popliteal artery branching patterns and a new subclassification of the ‘usual’ branching pattern. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2017, 39, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. Generic substitution rate at 1.25%... Post-substitution physician notification cited as key reason for the low rate. Daily Pharm Korea, 29 November 2024. Available online: https://www.dailypharm.com/Users/News/NewsView.html?ID=318060 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Lee, I.H.; Park, S.; Lee, E.K. Generic Utilization in the Korean National Health Insurance Market; Cost, Volume and Influencing Factors. Yakhak Hoeji 2014, 58, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, E.; Karigome, H.; Sakurada, T.; Satoh, N.; Ueda, S. Patients’ attitudes towards generic drug substitution in Japan. Health Policy 2011, 99, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, P.A. Potential concerns about generic substitution: Bioequivalence versus therapeutic equivalence of different amlodipine salt forms. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2009, 25, 2179–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Bioequivalence of generic drugs. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2015, 76, e1130–e1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesselheim, A.S.; Misono, A.S.; Lee, J.L.; Stedman, M.R.; Brookhart, M.A.; Choudhry, N.K.; Shrank, W.H. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2008, 300, 2514–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.Y.; Yang, B.M.; Kim, J.H. New anti-rebate legislation in South Korea. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2013, 11, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassali, M.A.; Alrasheedy, A.A.; McLachlan, A.; Nguyen, T.A.; Al-Tamimi, S.K.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Aljadhey, H. The experiences of implementing generic medicine policy in eight countries: A review and recommendations for a successful promotion of generic medicine use. Saudi Pharm. J. 2014, 22, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, G.; Yao, L.; Han, L.; Zheng, Q. Development of the generic drug industry in the US after the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2013, 3, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Policy Evaluation of the Price Policy for the Pharmaceuticals with Same Active Ingredients and the Management of Their Expenditures. National Health Insuarance Service. 2013. Available online: https://lib.nhis.or.kr/search/catalog/view.do?bibctrlno=2590&se=r1 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Anderson, G.V. Universal health care coverage in Korea. Health Aff. 1989, 8, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.H.; Bloor, K.; Hewitt, C.; Maynard, A. The effects of new pricing and copayment schemes for pharmaceuticals in South Korea. Health Policy 2012, 104, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. Pharmaceutical reform and physician strikes in Korea: Separation of drug prescribing and dispensing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Kim, E.S.; Lee, E.K. Evaluation of the chronic disease management program for appropriateness of medication adherence and persistence in hypertension and type-2 diabetes patients in Korea. Medicine 2017, 96, 26577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, N.; Singh, S.K.; Gulati, M.; Vaidya, Y.; Kaushik, M. Study of regulatory requirements for the conduct of bioequivalence studies in US, Europe, Canada, India, ASEAN and SADC countries: Impact on generic drug substitution. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, O.J.; Kanavos, P.G.; McKee, M. Comparing generic drug markets in Europe and the United States: Prices, volumes, and spending. Milbank Q. 2017, 95, 554–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, G.; Nanda, A.; Kotwani, A. A comparative evaluation of price and quality of some branded versus branded–generic medicines of the same manufacturer in India. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2011, 43, 131. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, E.R.; Aitken, M.L. Brand loyalty, generic entry and price competition in pharmaceuticals in the quarter century after the 1984 Waxman-Hatch legislation. Int. J. Econ. Bus. 2011, 18, 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, H.G.; Vernon, J.M. Brand loyalty, entry, and price competition in pharmaceuticals after the 1984 Drug Act. J. Law Econ. 1992, 35, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H.; Shepherd, M.D.; Scoones, D.; Wan, T.T. Product-line extensions and pricing strategies of brand-name drugs facing patent expiration. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2005, 11, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath Sanyal, S.; Datta, S.K. The effect of country of origin on brand equity: An empirical study on generic drugs. J. Product. Brand Manag. 2011, 20, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesselheim, A.S.; Misono, A.S.; Shrank, W.H.; Greene, J.A.; Doherty, M.; Avorn, J.; Choudhry, N.K. Variations in pill appearance of antiepileptic drugs and the risk of nonadherence. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-O. Pharmaceutical tendering system in outpatient sector in other countries and its implications. J. Distrib. Res. 2015, 20, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Grytten, J.; Sørensen, R. Practice variation and physician-specific effects. J. Health Econ. 2003, 22, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, A.J.; Nicholson, S. The formation and evolution of physician treatment styles: An application to cesarean sections. J. Health Econ. 2009, 28, 1126–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Lin, G.A.; Bardach, N.S.; Clay, T.H.; Boscardin, W.J.; Gelb, A.W.; Maze, M.; Gropper, M.A.; Dudley, R.A. Preoperative medical testing in Medicare patients undergoing cataract surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1530–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, M.; Gafni, A. Examining the role of the physician as a source of variation: Are physician-related variations necessarily unwarranted? J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.S.; Kassab, Y.W.; Taha, N.A.; Zainal, Z.A. Factors Impacting Pharmaceutical Prices and Affordability: Narrative Review. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerei, E.; Ghaffari, A.; Nikoobar, A.; Bastami, S.; Hamdghaddari, H. Interaction between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: A scoping review for developing a policy brief. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1072708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Issues | US | Korea |

|---|---|---|

| Substitutability Concern | Original vs. Generic | One Generic vs. Another |

| Names of Generic Drugs | INN (International Non-proprietary Name) | Proprietary Name |

| Prescribing | Mostly the Original’s Brand Name | The Original’s and Branded Generics’ Proprietary Names |

| Reputation of Generic Drug Manufacturers | Mostly None | Quite reputable for the top 10 Korean manufacturers |

| Barriers to Substitution | DAW (Dispense as written) | DAW and Requiring the pharmacy to notify the physician of the substitution. |

| Generic substitution at the pharmacy | Quite Often | Rare |

| Price Differential between Originators and Generics | Substantial | Negligible |

| Terminology for compensating physicians for prescribing certain drugs | Kickback | Rebate ‡ |

| Physician Perception on Bioequivalence | Positive Side | Negative Side |

| Pharmacy Practices | Mainly Large Corporate Practice | Small-Scale Independent Practice |

| Variables | Freq. (N) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 646,191 | 48.76 |

| Female | 679,143 | 51.24 | |

| Age | <50 | 115,146 | 8.69 |

| 50s | 327,368 | 24.70 | |

| 60s | 405,289 | 30.58 | |

| 70s | 348,742 | 26.31 | |

| ≥80 | 128,789 | 9.72 | |

| Insurance Type | NHIS | 1,244,245 | 93.88 |

| Medical Aid | 78,167 | 5.90 | |

| Veteran | 2922 | 0.22 | |

| Number of Sources * | ≥75 | 749,292 | 56.54 |

| 50–75 | 316,603 | 23.89 | |

| 25–50 | 171,335 | 12.93 | |

| <25 | 88,104 | 6.65 | |

| Total | 1,325,334 | 100.00 | |

| Variables | % Drug Therapies | MSPS (Switching Rate per 100) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freq. (N) | Percent (%) | Mean | S.D. | C.V. | |

| Selected Formulations of BE Drug Therapy | |||||

| Glimepiride 2 mg | 213,341 | 16.1 | 29 | 45 | 1.55 |

| Metformin hydrochloride 500 mg | 184,018 | 13.88 | 16 | 37 | 2.31 |

| Losartan potassium 50 mg | 176,068 | 13.28 | 20 | 40 | 2.00 |

| HCTZ 12.5 mg + Losartan 50 mg | 156,432 | 11.8 | 19 | 39 | 2.05 |

| Amlodipine maleate 5 mg | 123,940 | 9.35 | 8 | 28 | 3.50 |

| Valsartan 80 mg | 73,884 | 5.57 | 15 | 36 | 2.40 |

| HCTZ 12.5 mg + Valsartan 80 mg | 67,028 | 5.06 | 18 | 38 | 2.11 |

| Candesartan cilexetil 8 mg | 55,031 | 4.15 | 9 | 29 | 3.22 |

| HCTZ 12.5 mg + Candesartan 16 mg | 50,110 | 3.78 | 10 | 30 | 3.00 |

| Lercanidipine hydrochloride 10 mg | 46,753 | 3.53 | 12 | 33 | 2.75 |

| Pioglitazone HCL 15 mg | 45,600 | 3.44 | 19 | 39 | 2.05 |

| Felodipine 5 mg | 38,785 | 2.93 | 12 | 33 | 2.75 |

| Irbesartan 150 mg | 35,687 | 2.69 | 7 | 26 | 3.71 |

| Cilnidipine 10 mg | 16,424 | 1.24 | 1 | 10 | 10.00 |

| Enalapril maleate 10 mg | 15,133 | 1.14 | 16 | 37 | 2.31 |

| Gliclazide 80 mg | 11,480 | 0.87 | 6 | 23 | 3.83 |

| Glibenclamide 5 mg + Metformin 500 mg | 6325 | 0.48 | 3 | 17 | 5.67 |

| Voglibose 0.2 mg | 5169 | 0.39 | 4 | 18 | 4.50 |

| Olmesartan medoxomil 40 mg | 4126 | 0.31 | 8 | 28 | 3.50 |

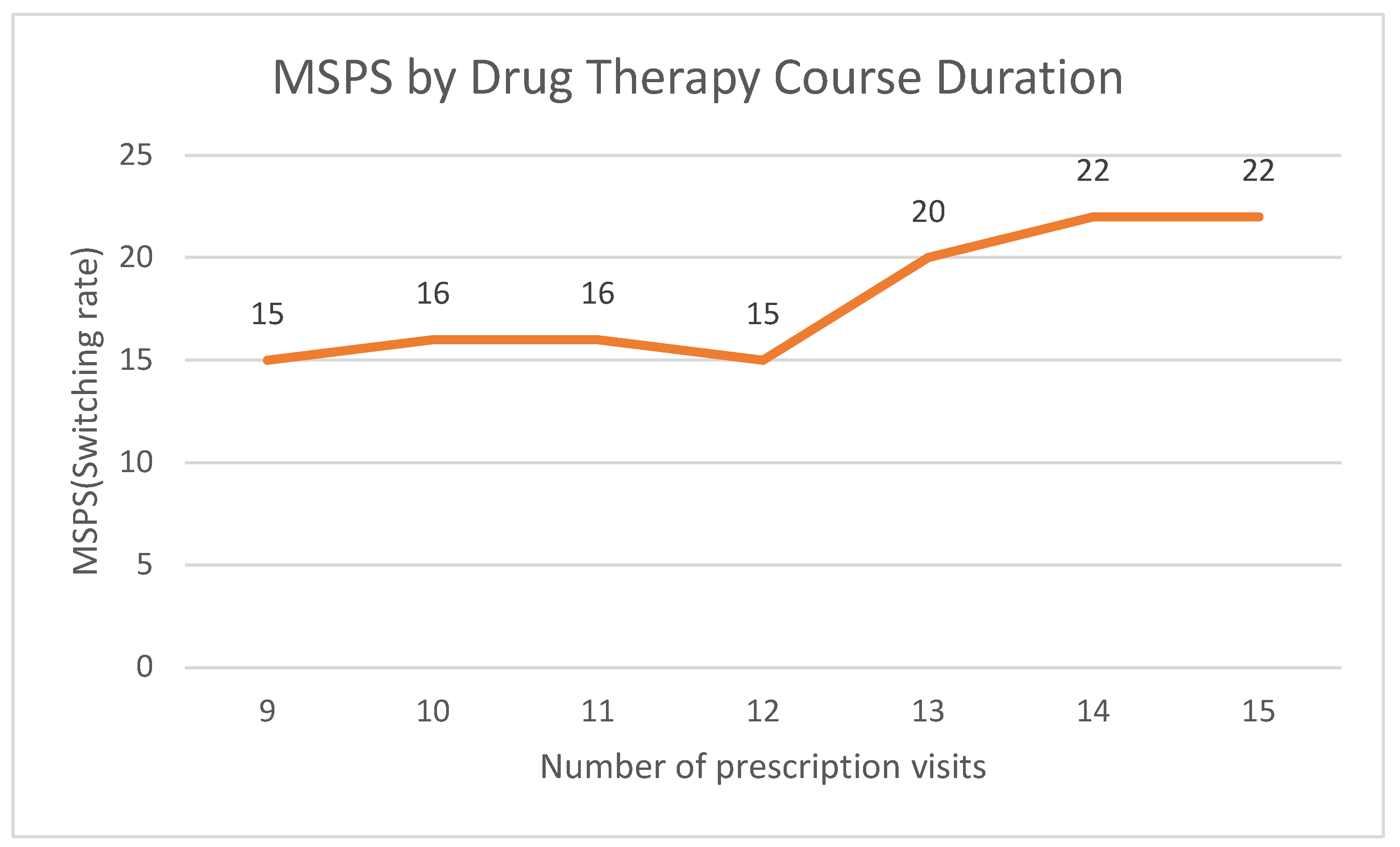

| Number of Prescription Visits | |||||

| 9 | 202,936 | 15.31 | 15 | 36 | 2.40 |

| 10 | 191,739 | 14.47 | 16 | 37 | 2.31 |

| 11 | 229,847 | 17.34 | 16 | 37 | 2.31 |

| 12 | 318,685 | 24.05 | 15 | 36 | 2.40 |

| 13 | 165,309 | 12.47 | 20 | 40 | 2.00 |

| 14 | 114,699 | 8.65 | 22 | 41 | 1.86 |

| 15 | 102,119 | 7.71 | 22 | 42 | 1.91 |

| Type of Physician Practices | |||||

| Tertiary Hospital | 58,986 | 4.45 | 15 | 36 | 2.40 |

| General Hospital | 169,065 | 12.76 | 16 | 36 | 2.25 |

| Hospital | 78,657 | 5.93 | 22 | 42 | 1.91 |

| Eldercare Hospital | 9986 | 0.75 | 22 | 42 | 1.91 |

| Clinic | 907,988 | 68.51 | 17 | 37 | 2.18 |

| Public Health Center | 76,626 | 5.78 | 17 | 38 | 2.24 |

| Public Health Center Branch * | 20,236 | 1.53 | 26 | 44 | 1.69 |

| Public Healthcare Facility ** | 3790 | 0.29 | 23 | 42 | 1.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.H.; Hong, S.H. Patterns of Prescription Switching in a Uniform-Pricing System for Multi-Source Drugs: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2339. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182339

Kim DH, Hong SH. Patterns of Prescription Switching in a Uniform-Pricing System for Multi-Source Drugs: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2339. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182339

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Dong Han, and Song Hee Hong. 2025. "Patterns of Prescription Switching in a Uniform-Pricing System for Multi-Source Drugs: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2339. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182339

APA StyleKim, D. H., & Hong, S. H. (2025). Patterns of Prescription Switching in a Uniform-Pricing System for Multi-Source Drugs: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study. Healthcare, 13(18), 2339. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182339