Understanding the Impact of Personal Resources on Emotional Exhaustion Among Emergency Healthcare Workers: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

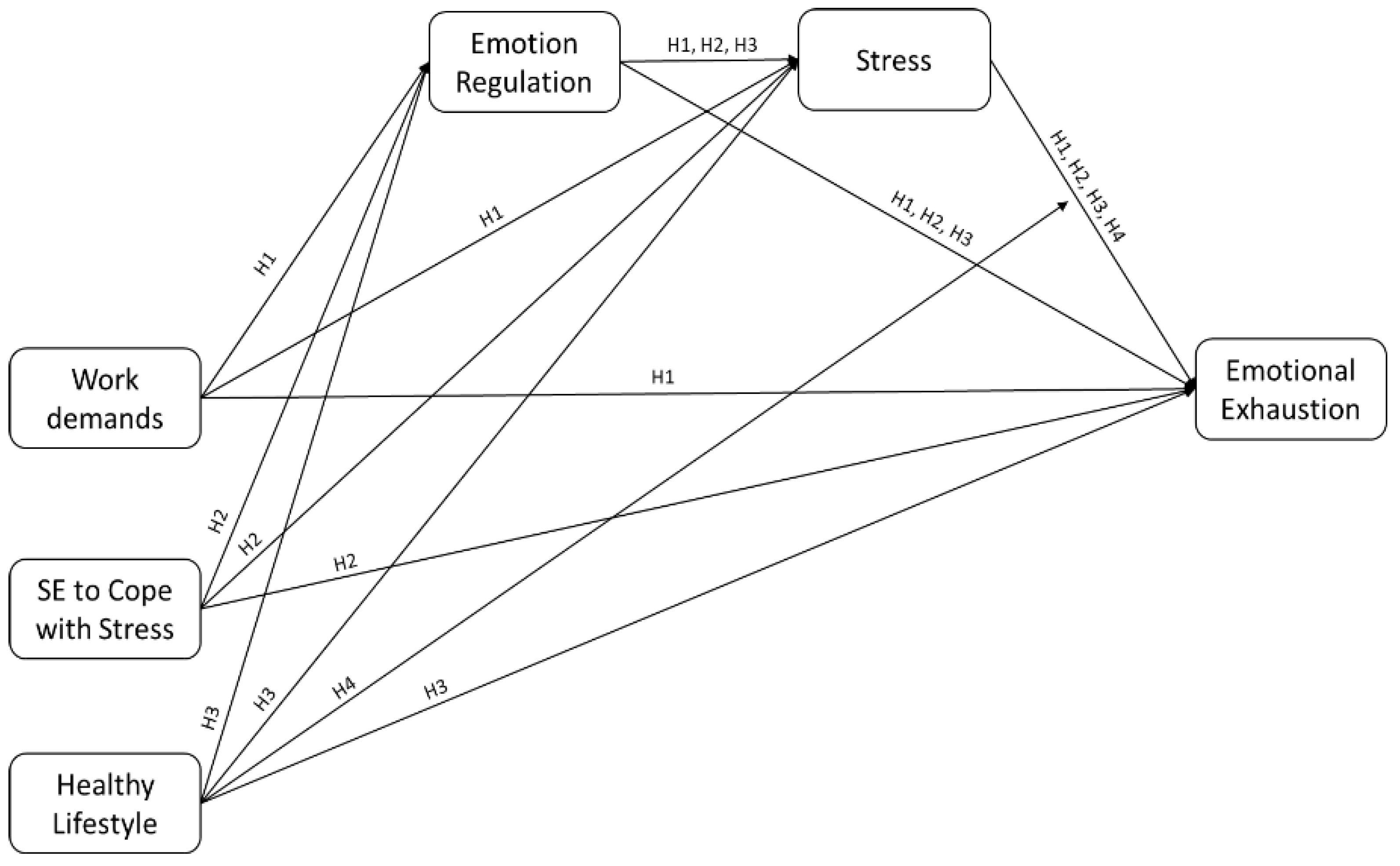

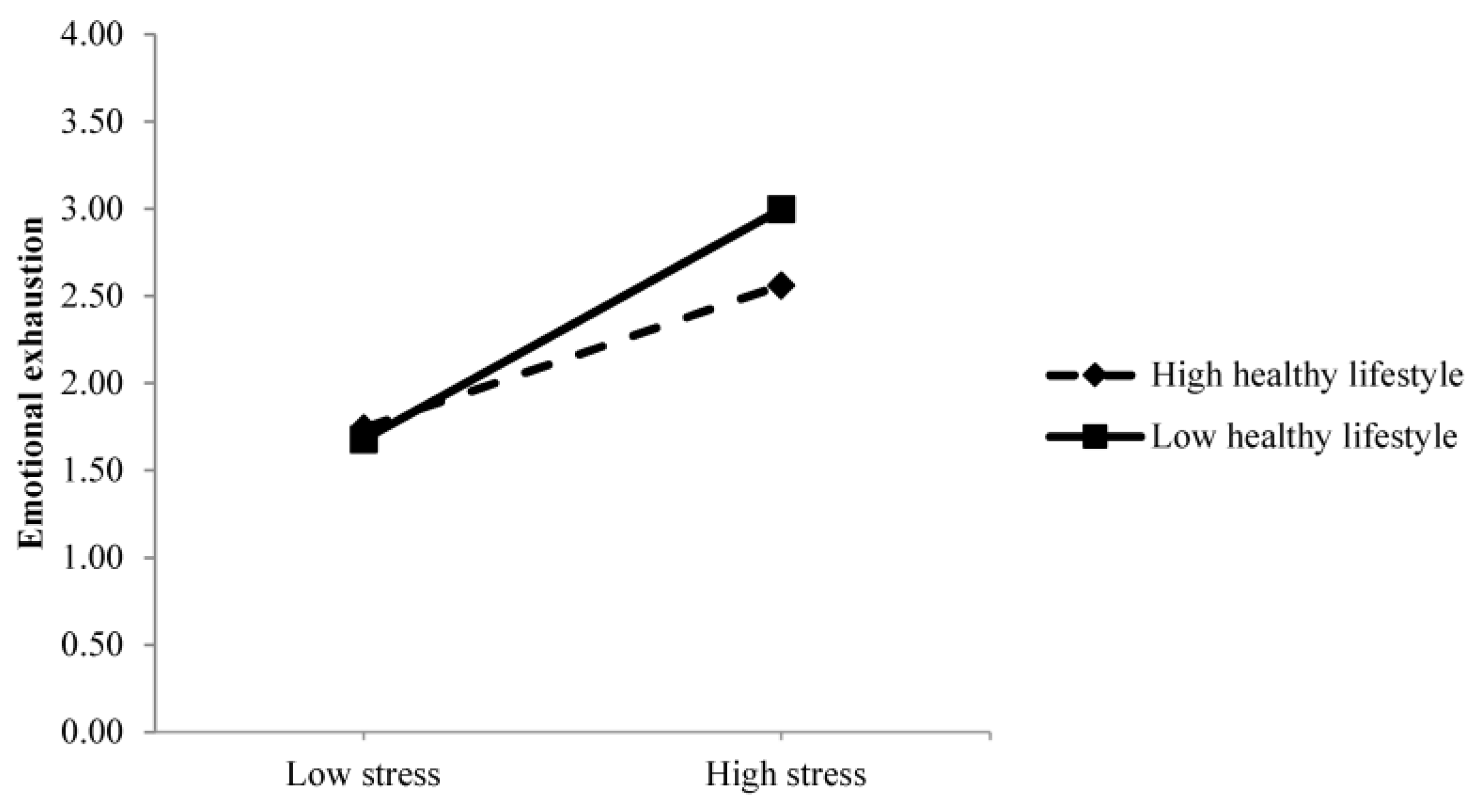

3.2. Mediation and Moderation Hypotheses

3.3. Predictive Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walton, M.; Murray, E.; Christian, M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Z.; Han, M.F.; Luo, T.D.; Ren, A.K.; Zhou, X.P. Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19. Chin. J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 2020, 38, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.P.; Kolcz, D.L.; O’Sullivan, D.M.; Ferrand, J.; Fried, J.; Robinson, K. Health care workers’ mental health and quality of life during COVID-19: Results from a mid-pandemic, national survey. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, S.; Oetjen, N.; Du, J.; Posenato, E.; Resende de Almeida, R.M.; Losada, R.; Ribeiro, O.; Frisardi, V.; Hopper, L.; Rashid, A.; et al. Mental health among medical professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in eight European countries: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koinis, A.; Giannou, V.; Drantaki, V.; Angelaina, S.; Stratou, E.; Saridi, M. The impact of healthcare workers’ job environment on their mental-emotional health. Coping strategies: The case of a local general hospital. Health Psychol. Res. 2015, 3, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Norman, I.; Xiao, T.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Leamy, M. Evaluating a psychological first aid training intervention (Preparing Me) to support the mental health and wellbeing of Chinese healthcare workers during healthcare emergencies: Protocol for a randomized controlled feasibility trial. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 809679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagni, M.; Maiorano, T.; Giostra, V.; Pajardi, D. Coping with COVID-19: Emergency stress, secondary trauma and self-efficacy in healthcare and emergency workers in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 566912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, K.; Sugawara, N.; Yasui-Furukori, N.; Danjo, K.; Furukori, H.; Sato, Y.; Tomita, T.; Fujii, A.; Nakagam, T.; Sasaki, M.; et al. Relationship between occupational stress and depression among psychiatric nurses in Japan. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2016, 71, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Ahn, Y.S.; Kim, K.; Yoon, J.H.; Roh, J. Association between job stress and occupational injuries among Korean firefighters: A nationwide cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Paneque, R.J.; Pavés-Carvajal, J.R.P. Occupational hazards and diseases among workers in emergency services: A literature review with special emphasis on Chile. Medwave 2015, 15, e6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 283, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; International Labour Organization. Caring for Those Who Care: Guide for the Development and Implementation of Occupational Health and Safety Programmes for Health Workers; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040779 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.; Leiter, M. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, J.; Brotheridge, C. Resources, coping strategies, and emotional exhaustion: A conservation of resources perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, D.R.; Matthews, L.M.; Ambrose, S.C. A meta-analytic review of emotional exhaustion in a sales context. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2019, 39, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiabane, E.; Gabanelli, P.; La Rovere, M.T.; Tremoli, E.; Pistarini, C.; Gorini, A. Psychological and work-related factors associated with emotional exhaustion among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italian hospitals. Nurs. Health Sci. 2021, 23, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: A systematic review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.N.; Azza, A.A. Burnout and coping methods among emergency medical services professionals. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvanova, R.K.; Muros, J.P. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 168–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Herrero, S.; Mariscal-Saldaña, M.Á.; García-Rodríguez, J.G.; Ritzel, D.O. Influence of task demands on occupational stress: Gender differences. J. Saf. Res. 2012, 43, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gynning, B.E.; Karlsson, E.; Teoh, K.; Gustavsson, P.; Christiansen, F.; Brulin, E. Contextualising the Job Demands–Resources Model: A Cross-Sectional Study of the Psychosocial Work Environment across Different Healthcare Professions. Hum. Resour. Health 2024, 22, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, D.R.; Stengård, J.; Ekström-Bergström, A.; Areskoug Josefsson, K.; Krettek, A.; Nyberg, A. Job Demands, Job Resources, and Health Outcomes among Nursing Professionals in Private and Public Healthcare Sectors in Sweden—A Prospective Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, B.; Brown Mahoney, C.; Xu, Y. Impact of Job Demands and Resources on Nurses’ Burnout and Occupational Turnover Intention—Toward an Age-Moderated Mediation Model for the Nursing Profession. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Role of Personal Resources in the Job Demands–Resources Model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands-Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, K.; Cieslak, R.; Smoktunowicz, E.; Rogala, A.; Benight, C.C.; Luszczynska, A. Associations between job burnout and self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Anxiety Stress Coping 2016, 29, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Grau, A.L. The influence of personal dispositional factors and organizational resources on workplace violence, burnout, and health outcomes in new graduate nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotel, A.; Golu, F.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Dimitriu, M.; Socea, B.; Cirstoveanu, C.; Davitoiu, A.M.; Jacota-Alexe, F.; Oprea, B. Predictors of burnout in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 1–604. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1994, 59, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Saudino, K.J. Emotion regulation and stress. J. Adult Dev. 2011, 18, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Koku, G.; Grime, P. Emotion regulation and burnout in doctors: A systematic review. Occup. Med. 2019, 69, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoensukmongkol, P. The contributions of mindfulness meditation on burnout, coping strategy, and job satisfaction: Evidence from Thailand. J. Manag. Organ. 2013, 19, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, I.; Malcolm, J. The benefits of mindfulness meditation: Changes in emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress. Behav. Change. 2012, 25, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Brufau, R.; Martin-Gorgojo, A.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Estrada, E.; Capriles-Ovalles, M.E.; Romero-Brufau, S. Emotion regulation strategies, workload conditions, and burnout in healthcare residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.C.J.; Durand-Bush, N.; Young, B.W. Self-regulation capacity is linked to wellbeing and burnout in physicians and medical students: Implications for nurturing self-help skills. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Iñigo, D.; Totterdell, P.; Alcover, C.M.; Holman, D. Emotional labour and emotional exhaustion: Interpersonal and intrapersonal mechanisms. Work. Stress 2007, 21, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Huang, S.; Wang, W. Work environment characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of emotion regulation strategies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, J. Healthy lifestyle changes and mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 13953–13962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balatoni, I.; Szépné, H.V.; Kiss, T.; Adamu, U.G.; Szulc, A.M.; Csernoch, L. The importance of physical activity in preventing fatigue and burnout in healthcare workers. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluut, H.; Wonders, J. Not able to lead a healthy life when you need it the most: Dual role of lifestyle behaviors in the association of blurred work-life boundaries with well-being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 607294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, H.K.; Barral, A.L.; Vincent, K.B.; Arria, A.M. Stress and burnout among graduate students: Moderation by sleep duration and quality. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2023, 28, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnentag, S.; Fritz, C. The Recovery Experience Questionnaire: Development and Validation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S.; Patras, J.; Adolfsen, F.; Richardsen, A.M.; Martinussen, M. Using the Job Demands–Resources Model to Evaluate Work-Related Outcomes among Norwegian Health Care Workers. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020947436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R. Job Content Instrument Questionnaire and User’s Guide, Version 1.1.; University of Massachusetts: Lowell, MA, USA, 1985.

- Moncada, S.; Llorens, C.; Andrés, R.; Moreno, N.; Molinero, E. Manual del Método CoPsoQ-istas21 (Versión 2) Para la Evaluación y la Prevención de Los Riesgos Psicosociales en Empresas con 25 o Más Trabajadores y Trabajadoras, VERSIÓN MEDIA.; Instituto Sindical de Trabajo, Ambiente y Salud: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Escobar Redonda, E. La evaluación del burnout profesional. Factorialización del MBI-GS. Un análisis preliminar. Ansiedad Estrés 2007, 7, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero, C.; Arenas, A.; Briones, E. Self-efficacy training programs to cope with highly demanding work situations and prevent burnout. In Handbook of Managerial Behavior and Occupational Health; Antoniou, A., Cooper, C., Chrousos, G., Spielberger, C., Eysenck, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009; pp. 278–291. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, G.V.; Di Giunta, L.; Eisenberg, N.; Gerbino, M.; Pastorelli, C.; Tramontano, C. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychol. Assess. 2008, 20, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyton, M.; Lobato, S.; Batista, M.; Aspano, M.A.; Jiménez, R. Validación del cuestionario de estilo de vida saludable (EVS) en una población española. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deporte 2018, 13, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide. Statistical Analysis with Latent Variables, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: http://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–816. [Google Scholar]

- Kinman, G.; Dovey, A.; Teoh, K. Burnout in Healthcare: Risk Factors and Solutions; Society of Occupational Medicine: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/Burnout_in_healthcare_risk_factors_and_solutions_July2023.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Pavlova, A.; Wang, C.X.; Boggiss, A.L.; O’Callaghan, A.; Consedine, N.S. Predictors of physician compassion, empathy, and related constructs: A systematic review. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.; Panagopoulou, E.; Esmail, A.; Richards, T.; Maslach, C. Burnout in healthcare: The case for organisational change. BMJ 2019, 366, l4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, D.S.; Profit, J.; Morgenthaler, T.I.; Satele, D.V.; Sinsky, C.A.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Tutty, M.A.; West, C.P.; Shanafelt, T.D. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, M.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Mousavi-Roknabadi, R.S. Burnout among healthcare providers of COVID-19: A systematic review of epidemiology and recommendations. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2021, 9, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jang, K.S. Nurses’ emotions, emotion regulation and emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2019, 27, 1409–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E.; Tabernero, C.; Fajardo, C.; Luque, B.; Arenas, A.; Moyano, M.; Castillo-Mayén, R. Type D Personality Individuals: Exploring the Protective Role of Intrinsic Job Motivation in Burnout. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 37, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, R.A.; Skaalvik, E.M. Principal self-efficacy: Relations with burnout, job satisfaction and motivation to quit. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012, 15, 295–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N.; Huyghebaert-Zouaghi, T.; Réveillère, C.; Colombat, P.; Fouquereau, E. The effects of job demands on nurses’ burnout and presenteeism through sleep quality and relaxation. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulchar, R.J.; Haddad, M.B. Preventing burnout and substance use disorder among healthcare professionals through breathing exercises, emotion identification, and writing activities. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2022, 29, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, C.; Carlotto, M.S.; Kaiseler, M.; Dias, S.; Pereira, A.M. Predictors of burnout among nurses: An interactionist approach. Psicothema 2013, 25, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanullah, S.; Ramesh Shankar, R. The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: A review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.J.; Machowski, S.; Holdsworth, L.; Kern, M.; Zapf, D. Age, emotion regulation strategies, burnout, and engagement in the service sector: Advantages of older workers. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 33, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huang, C.; Cheung, S.P.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, J. Job demands and resources, burnout, and psychological distress of social workers in China: Moderation effects of gender and age. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 741563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (0 = male; 1= female) | - | |||||||

| 2. Work demands | 3.07 | 0.68 | 0.14 | - | ||||

| 3. Stress | 2.81 | 0.95 | 0.30 ** | 0.63 ** | - | |||

| 4. Self-efficacy to cope with stress | 4.27 | 0.67 | 0.12 | −0.10 | −0.27 ** | - | ||

| 5. Emotion regulation | 3.59 | 0.86 | −0.25 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.57 ** | 0.51 ** | - | |

| 6. Healthy lifestyle | 3.21 | 0.57 | −0.10 | −0.19 * | −0.40 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.42 ** | - |

| 7. Emotional exhaustion | 2.25 | 1.17 | 0.25 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.75 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.49 ** | −0.40 ** |

| Emotion Regulation (M1) | Stress (M2) | Emotional Exhaustion (Y) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (H1) | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE |

| Work demands (X) | −0.24 *** | 0.09 | 0.52 *** | 0.07 | 0.20 ** | 0.11 |

| Emotion regulation (M1) | - | - | −0.44 *** | 0.05 | −0.12 * | 0.08 |

| Stress (M2) | - | - | - | - | 0.56 *** | 0.09 |

| Model settings | R2 = 0.06 F (1, 187) = 11.429 *** | R2 = 0.58 F (2, 186) = 126.379 *** | R2 = 0.59 F (3, 185) = 88.673 *** | |||

| Indir. cond. effect Bootstrap (95% CI) | X → M1 → Y 0.030 [0.001, 0.068] | X → M2 → Y 0.291 [0.201, 0.387] | X → M1 → M2 → Y 0.059 [0.023, 0.101] | |||

| Model 2 (H2) | ||||||

| Self-efficacy (X) | 0.51 *** | 0.08 | 0.02 (ns) | 0.10 | 0.06 (ns) | 0.10 |

| Emotion regulation (M1) | - | - | −0.57 *** | 0.08 | −0.12 # | 0.09 |

| Stress (M2) | - | - | - | - | 0.70 *** | 0.07 |

| Model settings | R2 = 0.26 F (1, 187) = 64.740 *** | R2 = 0.32 F (2, 186) = 43.572 *** | R2 = 0.57 F (3, 185) = 81.784 *** | |||

| Indir. cond. effect Bootstrap (95% CI) | X → M1 → Y −0.063 [−0.155, 0.008] | X → M2 → Y 0.014 [−0.087, 0.120] | X → M1 → M2 → Y −0.203 [−0.303, −0.114] | |||

| Model 3 (H3) | ||||||

| Healthy lifestyle (X) | 0.42 *** | 0.10 | −0.20 ** | 0.11 | −0.10 # | 0.11 |

| Emotion regulation (M1) | - | - | −0.48 *** | 0.07 | −0.06 (ns) | 0.08 |

| Stress (M2) | - | - | - | - | 0.67 *** | 0.07 |

| Model settings | R2 = 0.18 F (1, 187) = 40.120 *** | R2 = 0.35 F (2, 186) = 50.378 *** | R2 = 0.57 F (3, 185) = 83.329 *** | |||

| Indir. cond. effect Bootstrap (95% CI) | X → M1 → Y −0.027 [−0.081, 0.030] | X → M2 → Y −0.134 [−0.228, −0.038] | X → M1 → M2 → Y −0.136 [−0.210, −0.079] | |||

| Without Correction Factor | With Correction Factor for MLR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | Value | 3.658 | Value | 2.648 |

| Degrees of Freedom | 3 | Degrees of Freedom | 3 | |

| p-Value | 0.3009 | p-Value | 0.4492 | |

| Scaling Correction Factor for MLR | 1.3814 | |||

| RMSEA | Estimate | 0.034 | Estimate | 0.000 |

| 90 Percent C.I. | 0.000–0.132 | 90 Percent C.I. | 0.000–0.117 | |

| Probability RMSEA ≤ 0.05 | 0.492 | Probability RMSEA ≤ 0.05 | 0.632 | |

| CFI/TLI | CFI | 0.998 | CFI | 1.000 |

| TLI | 0.991 | TLI | 1.006 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arenas, A.; Terán-Tinedo, V.; Cuadrado, E.; Castillo-Mayén, R.; Luque, B.; Tabernero, C. Understanding the Impact of Personal Resources on Emotional Exhaustion Among Emergency Healthcare Workers: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182336

Arenas A, Terán-Tinedo V, Cuadrado E, Castillo-Mayén R, Luque B, Tabernero C. Understanding the Impact of Personal Resources on Emotional Exhaustion Among Emergency Healthcare Workers: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182336

Chicago/Turabian StyleArenas, Alicia, Valeria Terán-Tinedo, Esther Cuadrado, Rosario Castillo-Mayén, Bárbara Luque, and Carmen Tabernero. 2025. "Understanding the Impact of Personal Resources on Emotional Exhaustion Among Emergency Healthcare Workers: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182336

APA StyleArenas, A., Terán-Tinedo, V., Cuadrado, E., Castillo-Mayén, R., Luque, B., & Tabernero, C. (2025). Understanding the Impact of Personal Resources on Emotional Exhaustion Among Emergency Healthcare Workers: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Healthcare, 13(18), 2336. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182336