Learning from the Implementation of Disability-Inclusive Maternity Care: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

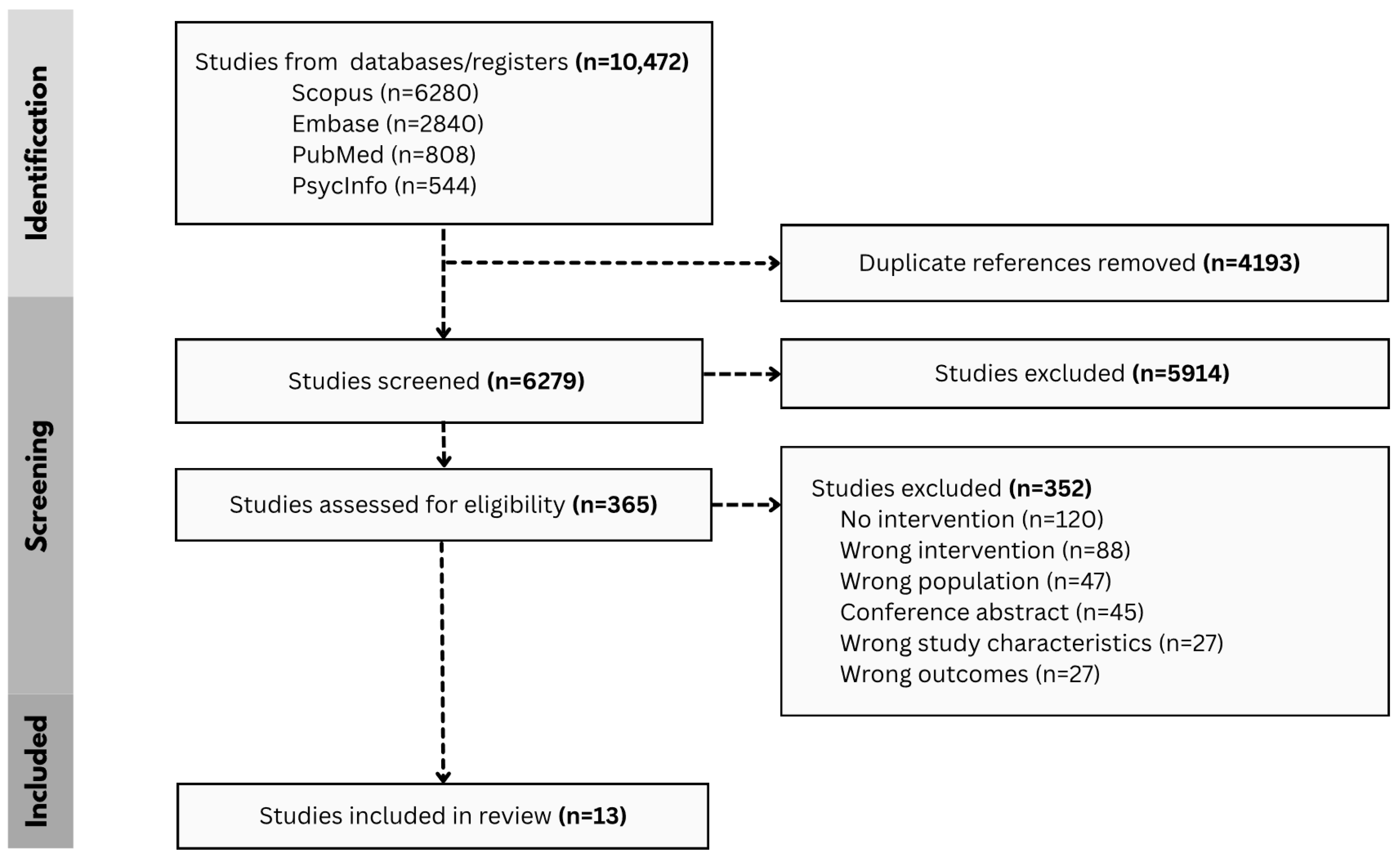

2. Materials and Methods

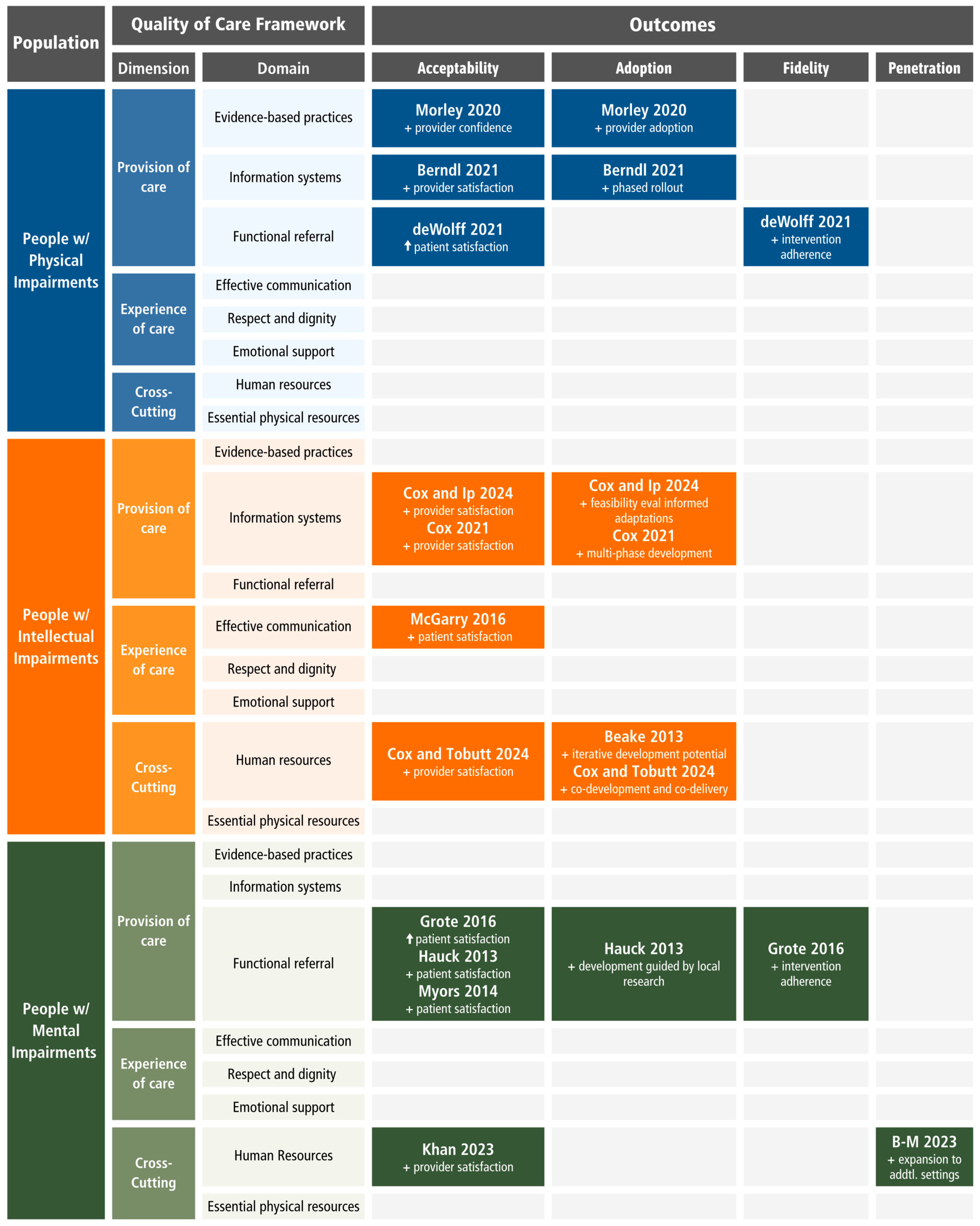

3. Results

3.1. Physical Impairments

3.2. Intellectual Impairments

3.3. Mental Impairments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRPD | Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |

| ED | Eating Disorders |

| ICF | International Classification on Functioning and Disability |

| ID | Intellectual Disabilities |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| MH | Mental Health |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| OB | Obstetrician |

| OBGYN | Obstetrics and Gynecology |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| SMI | Severe Mental Illness |

| US | United States |

| UN | United Nations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| PwD | People with Disabilities |

| PwPD | People with Physical Disabilities |

References

- World Health Organization; World Bank. World Report on Disability; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Signore, C.; Davis, M.; Tingen, C.M.; Cernich, A.N. The Intersection of Disability and Pregnancy: Risks for Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner-Johnson, W.; Darney, B.G.; Kulkarni-Rajasekhara, S.; Quigley, B.; Caughey, A.B. Pregnancy among US Women: Differences by Presence, Type, and Complexity of Disability. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 529.e1–529.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akobirshoev, I.; Vetter, M.; Horner-Johnson, W.; Lomerson, N.; Moore Simas, T.A.; Mitra, M. Severe Maternal Morbidity by Disability Status and Type in the United States. O&G Open 2024, 1, 027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H.W.J.; Poston, L.; Wilson, C.A.; Sheehan, R.; Sethna, V. Pregnancy and Postnatal Outcomes for Women with Intellectual Disability and Their Infants: A Systematic Review. Midwifery 2025, 142, 104298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleason, J.L.; Grewal, J.; Chen, Z.; Cernich, A.N.; Grantz, K.L. Risk of Adverse Maternal Outcomes in Pregnant Women with Disabilities. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2138414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, L.; Sadowsky, M.; Tao, S.; Rast, J.; Schendel, D.; Chesnokova, A.; Headen, I. Perinatal and Postpartum Health Among People With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2428067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, H.; Rodriguez, D. Disparities in Maternity Care for Disabled Women in the UK; International Centre for Evidence in Disability, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Missing Billion Initiative: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; Res 61/106; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Hundley, V.; Collins, B.; Ireland, J. Dignity and Respect during Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Survey of the Experience of Disabled Women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasoff, L.A.; Lunsky, Y.; Welsh, K.; Proulx, L.; Havercamp, S.M.; Parish, S.L.; Brown, H.K. Unmet Needs, Limited Access: A Qualitative Study of Postpartum Health Care Experiences of People with Disabilities. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 3324–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Thomas, A.; Brown, R.; Kinser, P.A. The Care Experiences of Pregnant Women with Serious Mental Illness: A Scoping Review. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2025, 31, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, A.; Cao, J.; Wilson, A.; Homer, C. Access to, and Experiences of, Maternity Care for Women with Physical Disabilities: A Scoping Review. Midwifery 2022, 107, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiedzadeh, M.; Khanjani, M.S.; Abdi, K.; Latifian, M. Content Analysis of Barriers to Delivering Maternity Care to Women with Physical Disabilities: A Qualitative Study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, G.; Brown, H.K.; Lunsky, Y.; Welsh, K.; Proulx, L.; Havercamp, S.; Tarasoff, L.A. Barriers to and Facilitators of Effective Communication in Perinatal Care: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Birthing People with Sensory, Intellectual, and/or Developmental Disabilities. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ven, C.; Marella, M.; Vaughan, C.; Slade, S.; Devine, A. Factors Influencing the Capacity of Healthcare Providers to Deliver Disability-Inclusive Maternity Care Services: A Scoping Review. Midwifery 2025, 143, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.; Foley, S.; Larkin, F. Understanding the Experiences of Receiving and Providing Maternity Care for Autistic Adults: A Multi-Perspectival Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis Study. Autism 2025, 29, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panko, T.L.; Cuculick, J.; Albert, S.; Smith, L.D.; Cooley, M.M.; Herschel, M.; Mitra, M.; McKee, M. Experiences of Pregnancy and Perinatal Healthcare Access of Women Who Are Deaf: A Qualitative Study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 130, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, J.K.; Buchanan, K.; Bayes, S. The Neurodivergent Perinatal Experience—A Systematic Literature Review on Autism and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Women Birth 2024, 37, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, B.; Hall, J.; Hundley, V.; Ireland, J. Effective Communication: Core to Promoting Respectful Maternity Care for Disabled Women. Midwifery 2023, 116, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratakonda, S.; Panko, T.L.; Albert, S.; Smith, L.D.; Cooley, M.M.; Mitra, M.; McKee, M. Wait, What? What’s Going On?—Pregnancy Experiences of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Mothers Who Do Not Sign. Birth 2025, 52, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatabira, M.; Ekirapa-Kiracho, E.; Aanyu, C.; Tan, H.-L.; Apolot, R.R.; Zia, N.; Kajungu, D.; Bachani, A.M.; Morgan, R. Improving Access to Skilled Maternal Health Services among Pregnant Women with Disabilities in Uganda: What Are Disability-Responsive Maternal Health Services? SSM—Health Syst. 2025, 5, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzoni, L.I.; Wint, A.J.; Smeltzer, S.C.; Ecker, J.L. Physical Accessibility of Routine Prenatal Care for Women with Mobility Disability. J. Women’s Health 2015, 24, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpakjian, C.Z.; Mulenga, L.; McIntosh, S.M.; Kreschmer, J.M.; Parten, R.; Haapala, H.; Langen, E.S.; Rosenblum, S.A.S.; Pazhyanur, S.; Carlson, S.; et al. Pregnancy and Physical Disability: A Scoping Review. Women’s Health 2025, 21, 17455057251338424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaminti, A.; Sarantaki, A.; Gourounti, K.; Lykeridou, A. Perinatal Care in Women with Vision Disorders: A Systematic Review. Maedica 2021, 16, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Tarasoff, L.A.; Lunsky, Y.; Welsh, K.; Proulx, L.; Havercamp, S.M.; Parish, S.L.; Brown, H.K. Disability Justice and Collective Access to Labour and Delivery Care: A Qualitative Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeltzer, S.C.; Mitra, M.; Long-Bellil, L.; Iezzoni, L.I.; Smith, L.D. Obstetric Clinicians’ Experiences and Educational Preparation for Caring for Pregnant Women with Physical Disabilities: A Qualitative Study. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, A.; Alvarado, M.; Ruiz, S.; King, T.; Cruz, T.; Davis, M.; Wallace, J. Disability and Pregnancy: Research from NIDILRR and NICHD; Administration for Community Living: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, M.; Akobirshoev, I.; Moring, N.S.; Long-Bellil, L.; Smeltzer, S.C.; Smith, L.D.; Iezzoni, L.I. Access to and Satisfaction with Prenatal Care Among Pregnant Women with Physical Disabilities: Findings from a National Survey. J. Women’s Health 2017, 26, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, M.; Smith, L.D.; Smeltzer, S.C.; Long-Bellil, L.M.; Sammet Moring, N.; Iezzoni, L.I. Barriers to Providing Maternity Care to Women with Physical Disabilities: Perspectives from Health Care Practitioners. Disabil. Health J. 2017, 10, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makeroufa, C.; Diamanti, A. Exploring Perinatal Care and Birth Experiences in Women with Visual Impairment: A Retrospective Study. Med. Int. 2024, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Access to Obstetric and Gynecologic Care for Patients with Disabilities; Committee Statement No. 18; ACOG: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; pp. 553–563. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities: A Guide for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Malouf, R.; Redshaw, M.; Kurinczuk, J.J.; Gray, R. Systematic Review of Heath Care Interventions to Improve Outcomes for Women with Disability and Their Family during Pregnancy, Birth and Postnatal Period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001; ISBN 978-92-4-154542-6. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, N. Disability Search Tips and Resources. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2015, 34, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioerger, M.; Flanders, R.M.; Goss, K.D.; Turk, M.A. Developing a Systematic Search Strategy Related to People with Disability: A Brief Report Testing the Utility of Proposed Disability Search Terms in a Search about Opioid Use. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.S.; Peterson, J.J.; Judkins, D.Z. Searching for Disability in Electronic Databases of Published Literature. Disabil. Health J. 2014, 7, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clifford, S.; Mary, M.; Interventions to Improve the Quality of Maternity Care for People with Disabilities: A Scoping Review. Open Science Framework (OSF) Registries. Available online: https://osf.io/j7qdb (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Standards for Improving Quality of Maternal and Newborn Care in Health Facilities; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-92-4-151121-6. [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review Software. 2024. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- UNRWA. Promoting the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Disability Toolkit: Classifying Disability; United Nations Relief and Works Agency: Amman, Jordan, 2013; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndl, A.; Khatib, S. Fetal Ultrasound Challenges and Solutions for Scanning Pregnant People with Physical Disabilities: A Two-Year Initiative for Adaptation. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2021, 43, 1005–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wolff, M.G.; Midtgaard, J.; Johansen, M.; Rom, A.L.; Rosthøj, S.; Tabor, A.; Hegaard, H.K. Effects of a Midwife-Coordinated Maternity Care Intervention (ChroPreg) vs. Standard Care in Pregnant Women with Chronic Medical Conditions: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, K. Reducing Risks for Pregnant Women with Epilepsy: A Qualitative Study Exploring Experiences of Using a Toolkit at the Antenatal Booking Appointment. Epilepsy Behav. 2020, 103, 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beake, S.; Clark, L.; Turner, T.; Bick, D. A Mixed Methods Study to Develop and Pilot a Competency Assessment Tool to Support Midwifery Care of Women with Intellectual Disabilities. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarry, A.; Stenfert Kroese, B.; Cox, R. How Do Women with an Intellectual Disability Experience the Support of a Doula During Their Pregnancy, Childbirth and After the Birth of Their Child? J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 29, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Ip, A.; Watkin, S.; Matuska, G.; Bunford, S.; Gallagher, A.; Taylor, C. Implementing and Evaluating Resources to Support Good Maternity Care for Parents with Learning Disabilities: A Qualitative Feasibility Study in England. Midwifery 2024, 133, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Parsons, T.; Watkin, S.; Gallagher, A. Supporting the Delivery of Good Maternity Care for Parents with Learning Disabilities. Midwifery 2021, 102, 103073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Tobutt, D.; Harris, J.; Watkin, S.; Eynon, C.; Matuska, G. Learning Disability Awareness Training for Undergraduate Midwifery Students: Multi-Method Evaluation of a Co-Produced and Co-Delivered Educational Intervention in England. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 140, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.A.; Lilly, C.L.; DeFazio, C.; Claydon, E.A. “It Is More Isolating to Patients If You Aren’t Familiar with the Resources”: A Pilot Test of a Clinician Sensitivity Training on Eating Disorders in Pregnancy. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, N.K.; Katon, W.J.; Russo, J.E.; Lohr, M.J.; Curran, M.; Galvin, E.; Carson, K. A Randomized Trial of Collaborative Care for Perinatal Depression in Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Women: The Impact of Comorbid Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myors, K.A.; Schmied, V.; Johnson, M.; Cleary, M. “My Special Time”: Australian Women’s Experiences of Accessing a Specialist Perinatal and Infant Mental Health Service. Health Soc. Care Community 2014, 22, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, Y.; Allen, S.; Ronchi, F.; Faulkner, D.; Frayne, J.; Nguyen, T. Pregnancy Experiences of Western Australian Women Attending a Specialist Childbirth and Mental Illness Antenatal Clinic. Health Care Women Int. 2013, 34, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bachner-Melman, R.; Haim-Dahan, R.; Zohar, A.H. “Women Friendly”: A Childbirth Preparation Intervention in Israel for Women with Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Disability Summit. Global Disability Inclusion Report: Accelerating Disability Inclusion in a Changing and Diverse World; International Disability Alliance; UNICEF; Global Disability Summit: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.A.; Stein, P.J.; Weiss, D.; Lang, R. Health Care and the UN Disability Rights Convention. Lancet 2009, 374, 1796–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adigun, O.T.; Akinrinoye, O.; Obilor, H.N. Including the Excluded in Antenatal Care: A Systematic Review of Concerns for D/Deaf Pregnant Women. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. ADA Requirements: Effective Communication. Available online: https://www.ada.gov/resources/effective-communication/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. ADA Business Brief: Communicating with People Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing in Hospital Settings. Available online: https://www.ada.gov/resources/business-brief-hospital/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- U.S. Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Mobility Disabilities. Available online: https://www.ada.gov/resources/medical-care-mobility/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- MacLellan, J.; McNiven, A.; Kenyon, S. Provision of Interpreting Support for Cross-Cultural Communication in UK Maternity Services: A Freedom of Information Request. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 6, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton, J. Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-520-20795-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, D.; Magasi, S.; Novak, C.; Harniss, M. Conducting Accessible Research: Including People with Disabilities in Public Health, Epidemiological, and Outcomes Studies. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 2137–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekdache, G.N.; Berndl, A. Women with Physical Disability in Pregnancy Resident Education: A National Survey as a Needs Assessment for Curriculum Improvement in Obstetrics and Gynaecology in Canada. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taouk, L.H.; Fialkow, M.F.; Schulkin, J.A. Provision of Reproductive Healthcare to Women with Disabilities: A Survey of Obstetrician-Gynecologists’ Training, Practices, and Perceived Barriers. Health Equity 2018, 2, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, S.; Aitelli, A.; Dotters-Katz, S.; Kalpakjian, C. Obstetrics and Gynecology Resident Comfort in Caring for Pregnant People with Physical Disabilities. Am. J. Perinatol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leddy, M.A.; Jones, C.; Morgan, M.A.; Schulkin, J. Eating Disorders and Obstetric-Gynecologic Care. J. Women’s Health 2009, 18, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, A.; Eaves, T.; Newnham, E.; Melov, S.; Hilsabeck, C.; Baird, K.; Prussing, E.; Pasupathy, D. The Continuity Relationship Makes Caring for Women with Anxiety and Depression Easier, but It Is Also a Heavy Responsibility. Women Birth 2025, 38, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibralic, S.; Pickup, W.; Diaz, A.M.; Kohlhoff, J.; Karlov, L.; Stylianakis, A.; Schmied, V.; Barnett, B.; Eapen, V. The Impact of Midwifery Continuity of Care on Maternal Mental Health: A Narrative Systematic Review. Midwifery 2023, 116, 103546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, K.R.; Nguyen, T.A.; Pickup, W.; Cibralic, S.; Mendoza Diaz, A.; Barnett, B.; Eapen, V. Perinatal Continuity of Care for Mothers with Depressive Symptoms: Perspectives of Mothers and Clinicians. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1385120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhimannil, K.B.; Vogelsang, C.A.; Hardeman, R.R.; Prasad, S. Disrupting the Pathways of Social Determinants of Health: Doula Support during Pregnancy and Childbirth. J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, L.M.; Thoma, M.E.; Shenassa, E.D. The Role of Doulas in Respectful Care for Communities of Color and Medicaid Recipients. Birth 2022, 49, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis-Jacques, A.F.; Applequist, J.; Perkins, M.; Williams, C.; Joglekar, R.; Powis, R.; Daniel, A.; Wilson, R. Florida Doulas’ Perspectives on Their Role in Reducing Maternal Morbidity and Health Disparities. Women’s Health Issues 2024, 34, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Confederation of Midwives. Philosophy and Model of Midwifery Care; International Confederation of Midwives: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gebreyes, K.; Nelson, H.; Punch, M.; Bhatt, J.; Keita, M.; Chang, C. Maternal Health Inequities Persist. Can Digital Tools Be Part of the Solution? Deloitte Center for Health Solutions: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, J.; Hastie, R.; Walker, S.; Lindquist, A.; Tong, S. Telehealth in Antenatal Care: Recent Insights and Advances. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Health Equity for Persons with Disabilities, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-92-4-006360-0. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Kane, S. Towards an Agenda of Action and Research for Making Health Systems Responsive to the Needs of People with Disabilities. Lancet Reg. Health—West. Pac. 2024, 52, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, H.K.; Mitra, M. Improved Obstetric Care for People with Disabilities: An Urgent Call for Accessibility and Inclusion. J Women’s Health 2022, 31, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the Surgeon General (OSG). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Improve Maternal Health; Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Make Mothers Matter. Supporting Mothers with Disabilities: A Call for Enhanced Care and Resources; MMM: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bills, K.L.; Mills, B. Limitations When Conducting Quantitative Disability Research. J. Res. Initiat. 2022, 6, 10. [Google Scholar]

| Concept | Include | Exclude |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Setting |

|

|

| Comparison |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Study Type |

|

|

| Article Type |

|

|

| Date |

|

|

| Languages |

|

|

| Impairment | Definition [43] | Disabling Health Conditions 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Related to physical functions and structures of the body arising from birth or due to illness or injury. | i.e.,: Absence/loss of limbs, Arthritis, Cerebral Palsy, Epilepsy, Neuromuscular disorders, SCI/Paralysis |

| Sensory | Related to one or more of the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, touch, or smell. | i.e.,: Blindness, Deafness, Deaf-blindness, Speech loss |

| Intellectual | Relates to intellectual functioning (e.g., learning, reasoning, problem solving) and adaptive behavior (conceptual, social, practical skills). | i.e.,: ADHD, ASD, Down Syndrome, FAS, Learning and Developmental disorders |

| Mental 2 | Related to those actions and behaviors that an individual does to make friends and relationships, behave within accepted limits, and cope with feelings and emotions. | i.e.,: Mood, Eating, Personality, Psychotic and Trauma-related disorders |

| Domains | Definition [44] | Illustrative Constructs |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | The perception among patients and/or health system actors that the intervention is agreeable or satisfactory. |

|

| Adoption | The uptake and utilization of the intervention from the perspective of the implementer. |

|

| Fidelity | The degree to which the interventions were implemented as prescribed as intended. |

|

| Penetration | The organization or provider perspective of the level of integration or scale of intervention within the given setting. |

|

| Sustainability | The extent to which the intervention is maintained or institutionalized within a health system or non-clinical setting from the administrator/organization perspective. |

|

| Author and Date | Location | Population | QoC Domain | Description | Setting | Design | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Impairment(s) | |||||||

| Berndl 2021 [45] | Canada | Pregnant w/physical disabilities | Actionable information systems | Quality improvement approach employing enhanced information systems to identify and implement adaptations to sonography services | Specialty clinic within tertiary care hospital | Cross- sectional | 136 ultrasound scans from 23 patients |

| deWolff 2021 [46] | Denmark | Pregnant and postpartum w/chronic medical conditions a | Functional referral systems | Midwife coordinated and individualized care with consultations and specialized known midwives | Tertiary care hospital | RCT | 357 patients (131 intervention, 131 usual care) |

| Morley 2020 [47] | United Kingdom | Pregnant w/epilepsy | Evidence-based practices | Peer-reviewed maternity epilepsy shared-care toolkit for antenatal booking appointment | Multiple settings (NHS Trust b) | Qualitative | 4 community midwives (interviews) |

| Intellectual Impairment(s) | |||||||

| Beake 2013 [48] | United Kingdom | Pregnant w/ID | Competent & motivated human resources | Competency assessment tool to support midwifery care | Tertiary care hospital within NHS Trust b | Mixed methods | 23 midwives (focus groups), 46 midwives (pilot and survey) |

| McGarry 2016 [49] | United Kingdom | Pregnant and postpartum w/ID | Effective communication | Provision of doula care: emotional support, advice and information provision, tangible assistance, and advocacy | Not specified | Qualitative | 4 patients and 3 doulas (interviews) |

| Cox and Tobutt 2024 [52] | United Kingdom | Pregnant and postpartum w/learning disabilities | Competent & motivated human resources | Learning disability awareness training for undergraduate midwifery students (Pre-training materials and in-person content delivered by experts-by-experience c) | Academic setting (midwifery school) | Mixed methods | 83 midwifery students (pre-post survey), 7 experts-by-experience c (interviews) |

| Cox and Ip 2024; Cox 2021 [50,51] | United Kingdom | Pregnant w/learning disabilities | Actionable information systems | Development of a toolkit for maternity professionals with guidance on delivering high quality care and an accessible maternity care plan for patients | Multiple settings (NHS Trust b) | 2024: Mixed methods 2021: Qualitative | 2024: 17 midwives and 6 parents with learning disabilities (interviews) d 2021: 16 stakeholders e (interviews), 20 providers (pilot and survey) |

| Mental Impairment(s) | |||||||

| Khan 2023 [53] | United States | Pregnant w/ED | Competent & motivated human resources | Clinician sensitivity training including education and strategies for patient-centered care with de-stigmatizing language | Academic setting (medical school) | Mixed methods | 115 adult health care professionals (54 intervention, 61 reference document) |

| Grote 2016 [54] | United States | Pregnant w/probable diagnosis of MDD and/or dysthymia | Functional referral systems | Coordination and provision of depression care | Multiple settings (Public health centers, telehealth, community) | RCT | 168 eligible pregnant women f (83 intervention, 85 usual care) |

| Myors 2014 [55] | Australia | Pregnant and postpartum w/multiple MH issues | Functional referral systems | Coordination and provision of specialist perinatal and infant mental health care | Multiple settings (Home, health centers, public areas, telehealth) | Qualitative | 11 women who were discharged from services (interviews) |

| Hauck 2013 [56] | Australia | Pregnant w/SMI | Functional referral systems | Childbirth and antenatal mental health clinic w/multi-disciplinary model | Specialty clinic within tertiary care hospital | Qualitative | 41 women with SMI g (interviews) |

| Bachner-Melman 2023 [57] | Israel | Pregnant w/symptoms of PTSD | Competent & motivated human resources | Medical staff training on birth-oriented thinking, positive psychology, and trauma-informed care | Specialty clinics within tertiary care hospitals | Commentary | n/a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Clifford, S.; Mary, M.; Kramer, B.; Minihane, M.C.; Ratangee, B.; Gilmer, E.M.; Creanga, A.A. Learning from the Implementation of Disability-Inclusive Maternity Care: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182315

Clifford S, Mary M, Kramer B, Minihane MC, Ratangee B, Gilmer EM, Creanga AA. Learning from the Implementation of Disability-Inclusive Maternity Care: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182315

Chicago/Turabian StyleClifford, Sarah, Meighan Mary, Briana Kramer, Mairead C. Minihane, Brina Ratangee, Erin M. Gilmer, and Andreea A. Creanga. 2025. "Learning from the Implementation of Disability-Inclusive Maternity Care: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182315

APA StyleClifford, S., Mary, M., Kramer, B., Minihane, M. C., Ratangee, B., Gilmer, E. M., & Creanga, A. A. (2025). Learning from the Implementation of Disability-Inclusive Maternity Care: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(18), 2315. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182315