Home Difficulties Experienced by Male Firefighters in South Korea: A Qualitative Study on Work–Family Conflict

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Setting

2.3. Data Collection and Procedure

“Can you describe the difficulties you face at home owing to your work as a firefighter?”

Additional semi-structured prompts were employedto further explore the depth and complexity of their experiences and support the development of emergent themes, including: “In what ways does your role as a firefighter impact your family life?”, What types of family conflict have arisen because of your job?”, and “How do you manage work-related stress at home?”

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Rigor

3. Results

3.1. Acting as an Emergency Commander at Home

3.1.1. Heightened Arousal

“When my kids were about to run across the crosswalk, scenes from accident sites flashed through my mind, and I yelled at them more than necessary. My wife and children did not understand why I was so upset. I used to be calm, but now I get angry and irritable more often.”(Participant 9)

“Even on my day off, I take my phone into the bathroom in case I am called for emergency duty. I can never fully relax, even when I am off duty.”(Participant 15)

3.1.2. Sleep Disturbances Affecting the Spouse

“I jump up at the slightest noise at night, which causes my wife to lose sleep too. Eventually, she told me to sleep in another room. However, now that we have been sleeping separately for so long, it feels awkward to suggest sharing a bed again.”(Participant 27)

3.1.3. Authoritative Communication Leading to Conflict

“When my kids ask, ‘Why?’ I catch myself saying, ‘Just do as you are told,’ as if I am disciplining them in the field. My wife snapped back, ‘I am not your subordinate.’”(Participant 11)

3.2. Reinterpreting Traumatic Experiences After Marriage

3.2.1. Irritability or Withdrawal at Home After Traumatic Incidents

“After I had a family, accident scenes started to hit me harder. On such days, I either withdraw into silence or become irritable at home. If I am irritable, my wife gets angry; if I stay silent, she also gets upset…”(Participant 22)

3.2.2. Excessive Safety Warnings Toward Family

“After returning from a fire scene, I cannot stop telling them to change the power strip or unplug the cords—it is nonstop safety preaching.”(Participant 24)

“After seeing a bus crash, I would not let my kids go on school trips. They were very frustrated.”(Participant 1)

3.2.3. Increased Appreciation for Family

“After I return from a serious incident, I cannot help but think, ‘You never know what will happen tomorrow. I have to give my best to my family today.’”(Participant 21)

3.2.4. Greater Emotional Involvement in Incidents After Having Children

“When I see a child around my kids’ age involved in an accident, I cannot help but think of my own child. My hands shake, I tear up, and it becomes emotionally unbearable.”(Participant 22)

3.3. Physical and Emotional Exhaustion Due to Irregular Work Schedules

3.3.1. Inadequate Rest After Night Shifts

“When I come home after a night shift, my kids knock on the bedroom door asking to play, or they make noise. I end up not sleeping, and my eyes are always bloodshot.”(Participant 1)

3.3.2. Anxiety About Family’s Safety During Night Shifts

“During my 24-h shift, I cannot relax because I worry about my wife and kids being alone at home.”(Participant 4)

3.3.3. Heightened Conflict with Spouse over Childcare

“If one of our two kids gets sick, my wife has no one to take the child to the hospital or stay home with the other. She is completely worn out, and I come home totally exhausted. We end up fighting all the time.”(Participant 9)

3.3.4. Sacrificing Personal Plans Due to Emergency Mobilization

“During the summer, with all the typhoon and heavy rain warnings, I never know when I will be called in. Therefore, I give up summer vacations and even a simple beer in the evening.”(Participant 17)

3.4. National Heroes Misunderstood by Their Families

3.4.1. Families Consider Standby Time as Rest Time

“Everyone knows firefighting is dangerous; thus, my wife often worried about me. To ease her anxiety, I told her that we rarely get dispatched and that nothing serious happens. I even told her there were no calls last night. Then she assumes I have been resting all night and dumps all the housework and childcare on me.”(Participant 22)

3.4.2. Lack of Recognition for Post-Night-Shift Recovery Time

“The next day off is meant for rest after a night shift. However, my family treats it as a day out; thus, the moment I get home, they urge me to go on outings. I cannot say no, and I cannot rest either.”(Participant 26)

3.4.3. Complaints About Missing Important Family Events

“Given that I am always on duty during holidays, my wife and kids go to my parents’ place alone. We end up arguing every New Year’s.”(Participant 29)

“I could not attend my child’s kindergarten sports day because of work. Both my child and wife were really disappointed.”(Participant 8)

3.5. Guilt-Ridden and Indebted Superman

3.5.1. Guilt for Missing Important Family Moments

“My 24-h shifts definitely place a burden on my family. Therefore, I have given up my hobbies such as working out. I live each day with a constant sense of guilt.”(Participant 12)

3.5.2. Feeling Indebted to Family Members Who Endure a Lot

“We had planned a graduation trip for my child’s elementary school, but a colleague got injured and I had to cover his shift. We could not go. I have been ‘repaying’ that debt ever since—doing extra chores and childcare.”(Participant 21)

3.5.3. Guilt Toward Family Members Who Worry About Their Safety

“Every time there is a major fire, I know my family stays up all night checking the news to see if I am safe. They would not have to go through that if I had a regular office job. I always feel sorry for putting them through such stress.”(Participant 29)

3.5.4. Overextending Themselves to Compensate Their Families

“After a night shift, I try to take over all the childcare and housework so my wife can rest—because she suffers so much being married to a firefighter. Nonetheless, I am exhausted too, and one time I nodded off on a bench at the playground while my kid fell… I did not even notice. (laughs)”(Participant 23)

3.6. Endeavoring to Be Superman at Home as Well

3.6.1. Self-Control to Prevent Firefighter Traits from Affecting Family Life

“In summer, fan-related fires are common. Therefore, when I see the fan running in an empty room, I get really anxious—but I turn it off and hold back my words because I do not want to sound like I am nagging.”(Participant 12)

3.6.2. Concern About Passing ‘Bad Things’ to the Family

“I had to recover a body after a fall. I was so disturbed, I wanted comfort from my wife—but I kept it to myself, worrying it might traumatize her. Nonetheless, my expression gave it away. She got upset, saying, ‘Why do you look like that? Did I do something wrong? Just tell me!’”(Participant 7)

“After a fire, I am covered in soot and chemicals. Even though I shower and change at the station, I shower again at home and wash my work clothes separately before touching anyone.”(Participant 11)

3.6.3. Sharing Trauma with Their Spouse

“When I opened up about a difficult call, my wife said, ‘You can always talk to me.’ That support was such a comfort.”(Participant 22)

“One day, I could not eat or think straight after retrieving a severely mutilated body. When I told my wife I was unsure if I could keep doing this job, she said, ‘Quitting is not an option.’ That really hurt me.”(Participant 6)

3.6.4. Adjusting Daily Life to Maintain Work–Family Balance

“My wife and I both used to work shifts, and we hit our limits with childcare. She eventually switched to a daytime job. I feel guilty—it was a setback for her career.”(Participant 23)

“As a uniformed officer, I used to obsess over promotions. Studying for exams and entertaining senior officers kept me away from my family. One day, my wife asked for a divorce. That is when I gave up chasing promotions.”(Participant 16)

“After a night shift, we agreed that I get five hours of sleep—no questions asked. After that, I take over the chores and childcare. That agreement brought peace to our home.”(Participant 22)

3.6.5. Increased Caution to Reassure the Family

“Since becoming the head of a family, I have become extra cautious during every task. My safety means peace of mind for my family.”(Participant 17)

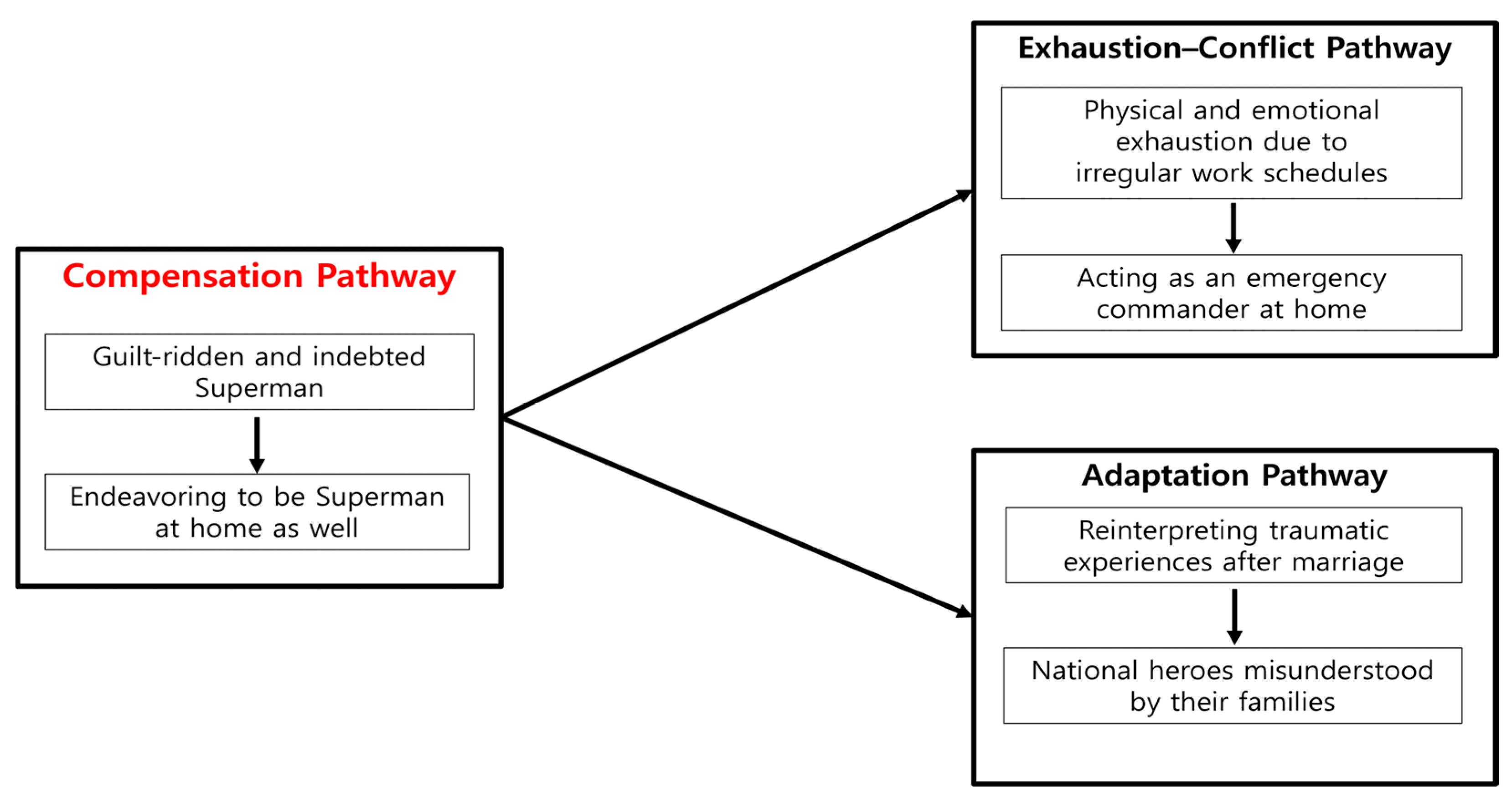

4. Discussion

4.1. Acting as an Emergency Commander at Home

4.2. Reinterpreting Traumatic Experiences After Marriage

4.3. Physical and Emotional Exhaustion Due to Irregular Work Schedules

4.4. National Heroes Misunderstood by Their Families

4.5. Guilt-Ridden and Indebted Superman

4.6. Endeavoring to Be Superman at Home as Well

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

References

- Arena, A.F.; Gregory, M.; Collins, D.A.J.; Vilus, B.; Bryant, R.; Harvey, S.B.; Deady, M. Global PTSD prevalence among active first responders and trends over recent years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2025, 120, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, D.E.; Lanham, S.N.; Martin, S.E.; Cleveland, R.E.; Wilson, T.E.; Langford, E.L.; Abel, M.G. Firefighter health: A narrative review of occupational threats and countermeasures. Healthcare 2024, 12, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, N.A.; Russell, J.; Hamadah, K.; Youngren, W.; Toon, A.; Nguyen, T.A.; Joles, K. Screening for comorbidity of sleep disorders in career firefighters. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 66, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, I.T.S.; Bourke, M.L.; Van Hasselt, V.B.; Black, R.A. Professional firefighters: Findings from the National Wellness Survey for Public Safety Personnel. Psychol. Serv. 2025, 22, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotunda, R.J.; Herzog, J.; Dillard, D.R.; King, E.; O’Dare, K. Alcohol misuse and correlates with mental health indicators among firefighters. Subst. Use Misuse 2025, 60, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; An, Y.; Li, X. Coping strategies as mediators in the relation between perceived social support and job burnout among Chinese firefighters. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, C.; An, Y.; Shi, J.; Huang, J.; Zhao, Y. Influence of avoidant coping on posttraumatic stress symptoms and job burnout among firefighters: The mediating role of perceived social support. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, M. Association between social support, and depressive symptoms among firefighters: The mediating role of negative coping. Saf. Health Work 2023, 14, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Kim, S. Posttraumatic growth in fire officers: A structural equation model. Crisisonomy 2025, 21, 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zegel, M.; Leonard, S.J.; McGrew, S.J.; Vujanovic, A.A. Firefighter relationship satisfaction: Associations with mental health outcomes. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2024, 52, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Fire Agency (Korea). National Fire Agency Statistical Yearbook 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.nfsa.go.kr/nfa/releaseinformation/statisticalinformation/main/?mode=view&cntId=72 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Lantz, E.; Nilsson, B.; Elmqvist, C.; Fridlund, B.; Svensson, A. Experiences and actions of part-time firefighters’ family members: A critical incident study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e086170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S.L.; Shannon, M.A.; Hurtado, D.A.; Shea, S.A.; Bowles, N.P. Interactions between home, work, and sleep among firefighters. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2021, 64, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.D.; Goodman, W.B.; Pirretti, A.E.; Almeida, D.M. Nonstandard work schedules, perceived family well-being, and daily stressors. J. Marriage Fam. 2008, 70, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilanawala, A.; McMunn, A. Nonstandard work schedules in the UK: What are the implications for parental mental health and relationship happiness? Community Work Fam. 2024, 27, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, L.; Keith, B. The effect of shift work on the quality and stability of marital relations. J. Marriage Fam. 1990, 52, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbesleben, J.R. The influence of shift work on emotional exhaustion in firefighters: The role of work–family conflict and social support. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2009, 2, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Deloy, D.M.; Dyal, M.-A.; Huang, G. Impact of work pressure, work stress and work–family conflict on firefighter burnout. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2019, 74, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Burn-Out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Fan, P.; Ye, L.; Yang, S.; Song, K.; Zhang, H.; Guo, M. High conflict, high performance? A time-lagged study on work–family conflict and family support congruence and safety performance. Saf. Sci. 2024, 172, 106403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Hughes, K.; Deloy, D.M.; Dyal, M.-A. Assessment of relationships between work stress, work–family conflict, burnout and firefighter safety behavior outcomes. Saf. Sci. 2018, 103, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, A.; Doyle, B.; Eppich, W.; Tjin, A.; Mulhall, C.; O’Toole, M. “This is it…this is our normal”—The voices of family members and first responders experiencing duty-related trauma in Ireland. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 133, 152499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, K.; van Hooff, M.; Doherty, M.; Iannos, M. Experiences and perceptions of family members of emergency first responders with post-traumatic stress disorder: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 629–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, R.; Sundin, E.; Winder, B. Work–family enrichment of firefighters: “Satellite family members”, risk, trauma and family functioning. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2020, 9, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, R.; Wagner, S.L. Firefighters and spouses: Hostility, satisfaction, and conflict. J. Fam. Issues 2023, 44, 1074–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hwang, H.; Pareliussen, J. Korea’s Unborn Future: Lessons from OECD Experience; OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1824; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C. Confucian Values and Democracy in South Korea. Rev. Korean Stud. 2013, 16, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C. Bringing the trauma home: Spouses of paramedics. J. Loss Trauma 2005, 10, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, A. The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. J. Phenomenol. Psychol. 2012, 43, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Shimazu, A.; Demerouti, E.; Shimada, K.; Kawakami, N. Work engagement versus workaholism: A test of the spillover–crossover model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, J.B.; Benuto, L.T. Work-related traumatic stress spillover in first responder families: A systematic review of the literature. Psychol. Trauma 2022, 14, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsavouni, F.; Bebetsos, E.; Malliou, P.; Beneka, A. The relationship between burnout, PTSD symptoms and injuries among ambulance personnel. Sport Sci. 2016, 9, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, R.; Ricciardelli, R.; Dekel, R.; Norris, D.; Mahar, A.; MacDermid, J.; Fear, N.T.; Gribble, R.; Cramm, H. Exploring the occupational lifestyle experiences of the families of public safety personnel. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2024, 34, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: New considerations. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boini, S.; Bourgkard, E.; Ferrières, J.; Esquirol, Y. What do we know about the effect of night-shift work on cardiovascular risk factors? An umbrella review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1034195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yin, X.; Gong, Y. Lifestyle factors in the association of shift work and depression and anxiety. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2328798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presser, H.B. Nonstandard work schedules and marital instability. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 62, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Jenkins, M.; Goldberg, A.E.; Pierce, C.P.; Sayer, A.G. Shift work, role overload, and the transition to parenthood. J. Marriage Fam. 2007, 69, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YTN. Firefighters Named Most Respected Profession for Third Consecutive Year. Available online: https://www.ytn.co.kr/_ln/0103_201605161429010077 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Hill, M.A.; Paterson, J.L.; Rebar, A.L. Secondary traumatic stress in partners of paramedics: A scoping review. Australas. Emerg. Care 2024, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Acting as an emergency commander at home | Heightened arousal Sleep disturbances affecting the spouse Authoritative communication leading to conflict |

| Reinterpreting traumatic experiences after marriage | Irritability or withdrawal at home after traumatic incidents Excessive safety warnings toward family Increased appreciation for family Greater emotional involvement in incidents after having children |

| Physical and emotional exhaustion due to irregular work schedules | Inadequate rest after night shifts Anxiety about family’s safety during night shifts Heightened conflict with spouse over childcare Sacrificing personal plans due to emergency mobilization |

| National heroes misunderstood by their families | Families consider standby time as rest time Lack of recognition for post-night-shift recovery time Complaints about missing important family events |

| Guilt-ridden and indebted Superman | Guilt for missing important family moments Feeling indebted to family members who endure a lot Guilt toward family members who worry about their safety Overextending themselves to compensate their families |

| Endeavoring to be Superman at home as well | Self-control to prevent firefighter traits from affecting family life Concern about passing ‘bad things’ to the family Sharing trauma with their spouse Adjusting daily life to maintain work–family balance Increased caution to reassure the family |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, N.; Lee, H.-J. Home Difficulties Experienced by Male Firefighters in South Korea: A Qualitative Study on Work–Family Conflict. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182300

Lee N, Lee H-J. Home Difficulties Experienced by Male Firefighters in South Korea: A Qualitative Study on Work–Family Conflict. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182300

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Nayoon, and Hyun-Ju Lee. 2025. "Home Difficulties Experienced by Male Firefighters in South Korea: A Qualitative Study on Work–Family Conflict" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182300

APA StyleLee, N., & Lee, H.-J. (2025). Home Difficulties Experienced by Male Firefighters in South Korea: A Qualitative Study on Work–Family Conflict. Healthcare, 13(18), 2300. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182300