Supporting Meaningful Choices: A Decision Aid for Individuals Facing Existential Distress and Considering Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

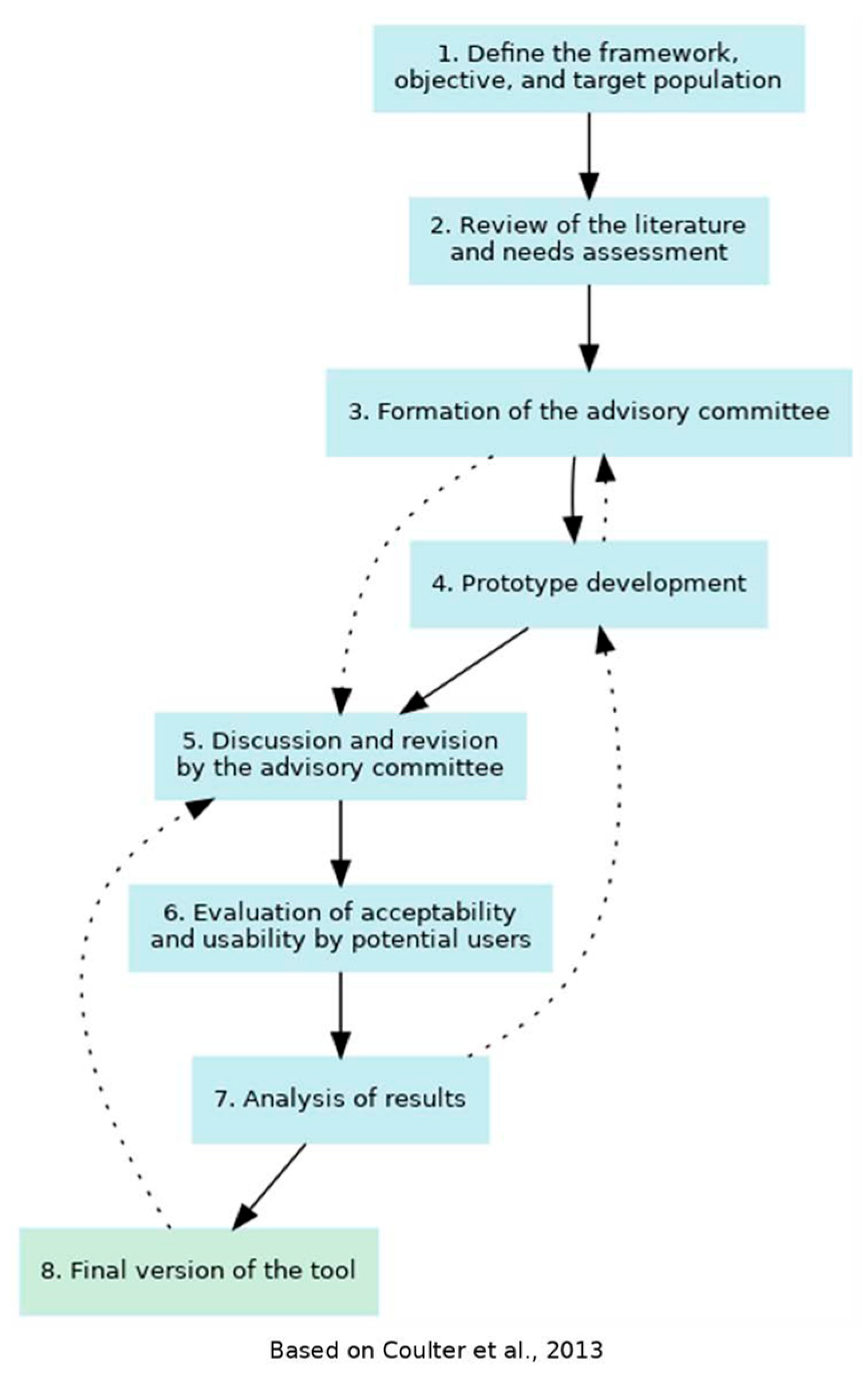

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Prototype Development

2.2. Evaluation of Prototype Acceptability and Usability

Sampling and Participant Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Reading Grid and Sociodemographic Questionnaire

2.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Prototype Development

3.2. Evaluation of Acceptability and Usability

Participant Characteristics

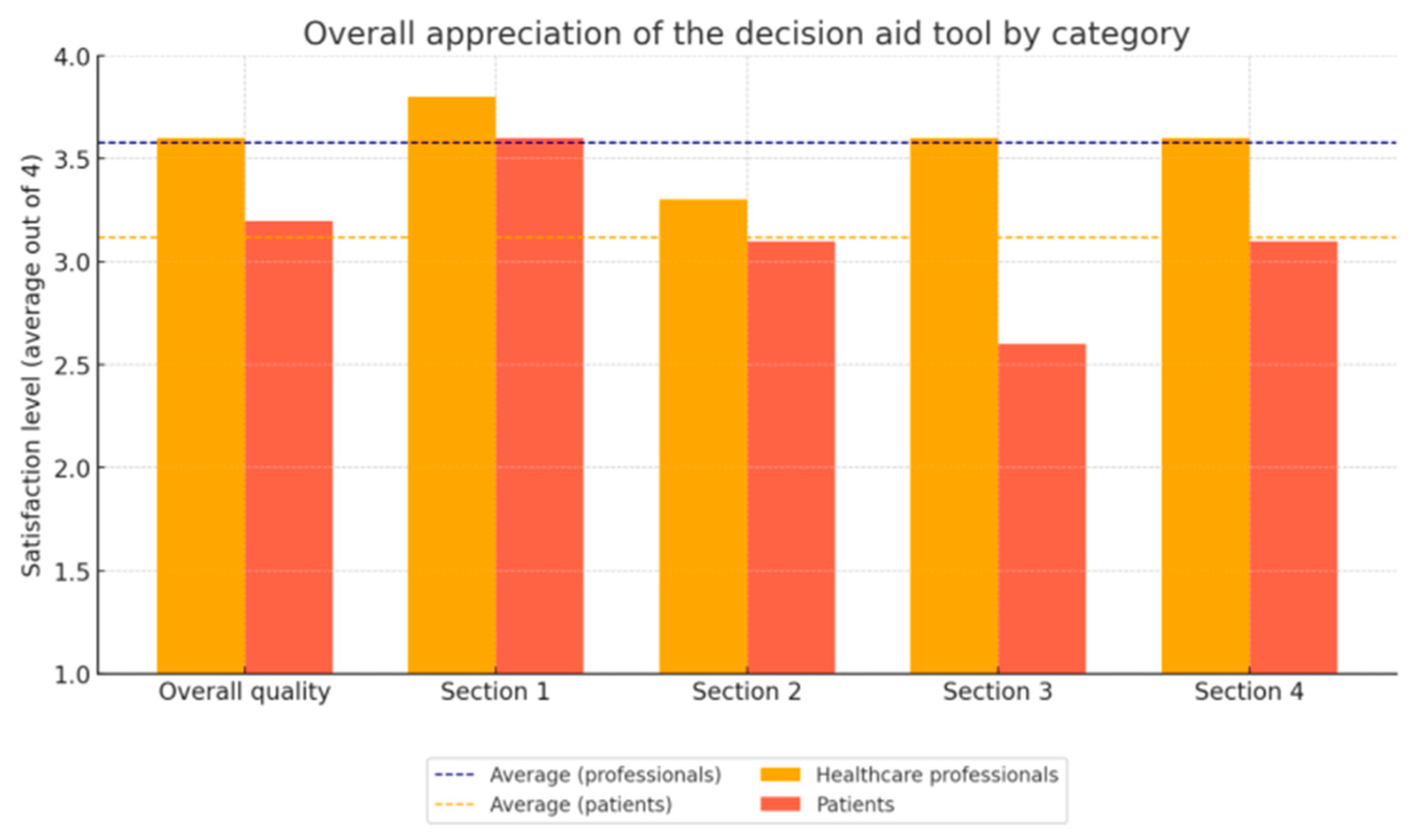

3.3. Evaluation Using the Reading Assessment Grid

3.4. Thematic Analysis of the Semi-Structured Interviews

- Theme 1: Balance of options

- Theme 2: Content

- Theme 3: Information clarity

- Theme 4: Length and structure

- Theme 5: Most appreciated features

3.5. Final Version of the Decision Aid

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Other Decision Aids

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Clinical Implications

4.4. Research Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| FAQ | Frequently Asked Questions |

| IPDAS | International Patient Decision Aids Standards Collaboration |

| PAT | Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy |

| SUNDAE | Standards for Universal Reporting of Patient Decision Aid Evaluation |

References

- LeMay, K.; Wilson, K.G. Treatment of existential distress in life threatening illness: A review of manualized interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 472–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, P.; Bruce, A.; Schreiber, R. Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 604–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.G.; Dalgleish, T.L.; Chochinov, H.M.; Chary, S.; Gagnon, P.R.; Macmillan, K.; De Luca, M.; O’Shea, F.; Kuhl, D.; Fainsinger, R.L. Mental disorders and the desire for death in patients receiving palliative care for cancer. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 6, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbart, W.; Chochinov, H. Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vehling, S.; Tian, Y.; Malfitano, C.; Shnall, J.; Watt, S.; Mehnert, A.; Rydall, A.; Zimmermann, C.; Hales, S.; Lo, C.; et al. Attachment security and existential distress among patients with advanced cancer. J. Psychosom. Res. 2019, 116, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byock, I. Taking Psychedelics Seriously. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostuzzi, G.; Matcham, F.; Dauchy, S.; Barbui, C.; Hotopf, M. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD011006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Carducci, M.A.; Umbricht, A.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D.; Cosimano, M.P.; Klinedinst, M.A. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Bossis, A.; Guss, J.; Agin-Liebes, G.; Malone, T.; Cohen, B.; Mennenga, S.E.; Belser, A.; Kalliontzi, K.; Babb, J.; et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapid, M.I.; Pagali, S.R.; Randall, A.L.; Donovan, K.A.; Bronars, C.A.; Gauthier, T.A.; Bock, J.; Lim, S.D.; Carey, E.C.; Sokolowski, E.; et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of psilocybin in alleviating distress among cancer patients: A systematic review. Palliat. Support. Care 2025, 23, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, M.; Farina, R.; Rachedi, K.; Laonigro, F.; Žuljević, M.F.; Pingani, L.; Ferrari, S.; Somers, M.; Boks, M.P.M.; Galeazzi, G.M. Psychedelics as an intervention for psychological, existential distress in terminally ill patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 02698811241303594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuman, H.D.M.; Savard, C.; Mina, R.; Barkova, S.; Conradi, H.S.W.; Deleemans, J.M.; Carlson, L.E. Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies for Psychosocial Symptoms in Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, V. Review of Psilocybin Use for Depression among Cancer Patients after Approval in Oregon. Cancers 2024, 16, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masse-Grenier, M.; Chang, S.L.; Belanger, A.; Stephan, J.F.; Hebert, J.; Deschamps, P.; Plourde, L.; Provost, F.; Farzin, H.; Fallu, J.S.; et al. What do health professionals think about implementing psilocybin-assisted therapy in palliative care for existential distress? A World Cafe qualitative study. Palliat. Support. Care 2024, 22, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, J.; Jafari, H.; Mantingh, T.; Bird, C.; Modlin, N.L.; Knight, G.; Reinholdt, F.; Day, C.; Carter, B.; Young, A. Psilocybin-assisted therapy for the treatment of resistant major depressive disorder (PsiDeR): Protocol for a randomised, placebo-controlled feasibility trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e056091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.M.; Neill, J.T. Exploring the relationship between mental health, drug use, personality, and attitudes towards psilocybin-assisted therapy. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2023, 7, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, C.A.; Lo, L.A.; Pistawka, C.A.; Deol, J.K. Therapeutic use of psilocybin: Practical considerations for dosing and administration. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1040217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, D.; Volk, R.J.; Leads, I.E.U. The International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration: Evidence Update 2.0. Med. Decis. Mak. 2021, 41, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, A.; Herrin, J.; Williams, M.D.; Inselman, J.W.; Branda, M.E.; Shah, N.D.; Heim, E.M.; Dick, S.R.; Linzer, M.; Boehm, D.H.; et al. Shared Decision Making for Antidepressants in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perestelo-Perez, L.; Rivero-Santana, A.; Sanchez-Afonso, J.A.; Perez-Ramos, J.; Castellano-Fuentes, C.L.; Sepucha, K.; Serrano-Aguilar, P. Effectiveness of a decision aid for patients with depression: A randomized controlled trial. Health Expect. Int. J. Public Particip. Health Care Health Policy 2017, 20, 1096–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.J.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Stacey, D.; Elwyn, G. Ten years of the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration: Evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13 (Suppl. S2), S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A. Modèle D’aide à la Décision D’ottawa; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sepucha, K.R.; Abhyankar, P.; Hoffman, A.S.; Bekker, H.L.; LeBlanc, A.; Levin, C.A.; Ropka, M.; Shaffer, V.A.; Sheridan, S.L.; Stacey, D.; et al. Standards for UNiversal reporting of patient Decision Aid Evaluation studies: The development of SUNDAE Checklist. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2018, 27, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, A.; Stilwell, D.; Kryworuchko, J.; Mullen, P.D.; Ng, C.J.; van der Weijden, T. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13 (Suppl. S2), S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; O’Connor, A.; Stacey, D.; Volk, R.; Edwards, A.; Coulter, A.; Thomson, R.; Barratt, A.; Barry, M.; Bernstein, S.; et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: Online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ 2006, 333, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Williams, N.; Newcombe, R.; Politi, M.; Durand, M.A.; Sivell, S.; Stacey, D.; O’Connor, A.; Volk, R.J.; Edwards, A.; Bennett, C.; et al. Toward Minimum Standards for Certifying Patient Decision Aids: A Modified Delphi Consensus Process. Med. Decis. Mak. 2014, 34, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Légaré, F.; Hebert, J.; Goh, L.; Lewis, K.B.; Leiva Portocarrero, M.E.; Robitaille, H.; Stacey, D. Do choosing wisely tools meet criteria for patient decision aids? A descriptive analysis of patient materials. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaffery, K.J.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Smith, S.K.; Rovner, D.; Nutbeam, D.; Clayman, M.L.; Kelly-Blake, K.; Wolf, M.S.; Sheridan, S. Adressing health literacy in patient decision aids. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13 (Suppl. S2), S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincaid, J.P.; Fishburne Jr, R.P.; Rogers, R.L.; Chissom, B.S. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel; University of Central Florida: Orlando, FL, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kasabwala, K.; Misra, P.; Hansberry, D.R.; Agarwal, N.; Baredes, S.; Setzen, M.; Eloy, J.A. Readability assessment of the American Rhinologic Society patient education materials. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013, 3, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, A.; Cranney, A. User Manual—Acceptability; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1996; 5p. [Google Scholar]

- Santerre-Theil, A.; Bouchard, K.; St-Pierre, D.; Drolet, A.M.; Chiquette, J.; Dorval, M.; Centre ROSE. Development of a Tool to Guide Parents Carrying a BRCA1/2 Mutation Share Genetic Results with Underage Children. J. Cancer Educ. 2018, 33, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K. Introduction. In Cognitive Interviewing Methodology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Willis, G.B. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Willson, S.; Miller, K. Data collection. In Cognitive Interviewing Methodology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 15–33. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Scholl, I.; Koelewijn-van Loon, M.; Sepucha, K.; Elwyn, G.; Légaré, F.; Harter, M.; Dirmaier, J. Measurement of shared decision making—A review of instruments. Z. Evidenz Fortbild. Qual. Gesundheitswesen 2011, 105, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legaré, F.; Graham, I.D.; O’Connor, A.M.; Dolan, J.G.; Bélanger-Ducharme, F. Prise de décision partagée: Traduction et validation d’une échelle de confort décisionnel du médecin. Pédagogie Médicale 2008, 4, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, P.; Gioxari, A.; Nimee, F.; Skouroliakou, M. Application of Clinical Decision Support System to Assist Breast Cancer Patients with Lifestyle Modifications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhyankar, P.; Volk, R.J.; Blumenthal-Barby, J.; Bravo, P.; Buchholz, A.; Ozanne, E.; Vidal, D.C.; Col, N.; Stalmeier, P. Balancing the presentation of information and options in patient decision aids: An updated review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13 (Suppl. S2), S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapp, D.; Blais, M.-C. Evaluation of decision support tools for patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review of literature. Palliat. Support. Care 2018, 17, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaussant, Y.; Sanders, J.; Sager, Z.; Tulsky, J.A.; Braun, I.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Bossis, A.P.; Byock, I. Defining the Roles and Research Priorities for Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies in Patients with Serious Illness: Expert Clinicians’ and Investigators’ Perspectives. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An overview of clinical decision support systems: Benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, N.; Bodegard, J.; Jerström, S.; Åkesson, J.; Brorsson, H.; Alfredsson, J.; Albertsson, P.A.; Karlsson, J.E.; Varenhorst, C. Effects of interactive patient smartphone support app on drug adherence and lifestyle changes in myocardial infarction patients: A randomized study. Am. Heart J. 2016, 178, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Sepúlveda, M.J.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Roebuck, M.C.; Shortliffe, E.H.; Yan, M.; et al. Effect of an Artificial Intelligence Clinical Decision Support System on Treatment Decisions for Complex Breast Cancer. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2020, 4, 824–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agin-Liebes, G.I.; Malone, T.; Yalch, M.M.; Mennenga, S.E.; Ponté, K.L.; Guss, J.; Bossis, A.P.; Grigsby, J.; Fischer, S.; Ross, S. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; Chen, M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, R.S. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ 2001, 322, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Patients, n = 5 |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 1 (20) |

| Female | 4 (80) |

| Age, n (%) | |

| 35–44 years | 1 (20) |

| 45–54 years | 1 (20) |

| 55–64 years | 2 (40) |

| 65 years and more | 1 (20) |

| Health conditions, n (%) | |

| Cancer | 3 (60) |

| Degenerative illness | 2 (40) |

| Education level, n (%) | |

| Undergraduate degree | 3 (60) |

| Graduate degree or higher | 2 (40) |

| Characteristics | Healthcare professional, n = 5 |

| Profession, n (%) | |

| Family physician | 3 (60) |

| Psychiatrist | 2 (40) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 3 (60) |

| Female | 2 (40) |

| Theme | Quotes | Summary of Content |

|---|---|---|

| Balance of options | “Well, I felt that it leaned more towards proposing psilocybin, but what are the other alternatives really? There aren’t many effective alternatives, and I think that’s a problem.” | Perceived imbalance favors PAT, but also acknowledges the limited availability of effective alternatives. |

| Content | “When you said that psilocybin-assisted therapy involves taking a large dose of psilocybin, I thought, oh my god, they’re going to give me a huge dose, I’ll feel terrible and have a bad trip.” | The term “large dose” was perceived as anxiety inducing; suggestion to replace it with “therapeutic dose” or “high dose.” |

| Clarity of information | “The values clarification table isn’t very clear. Maybe add the actual question directly instead of just the theme, or provide more context.” | Suggestion to improve the clarity of the tables to facilitate understanding. |

| Length | “Well, I found the tool maybe a little well, a little long. If it were more visual, I think it would be better.” | The tool is perceived as somewhat long; adding visual elements and removing less essential information is recommended to enhance accessibility. |

| Most appreciated | “Overall, I think the tool is really good. It covers all the essential questions.” | Overall positive appreciation; the tool is deemed as relevant and complete in addressing users’ needs. |

| Theme | Quotes | Summary of Content |

|---|---|---|

| Balance of options | “I found that it pushed a lot, a lot toward psilocybin-assisted therapy rather than toward other treatments. It feels like there’s a bias for psilocybin-assisted therapy, as if PAT is easy and works well, while other treatments are complicated and expensive.” | Perceived bias in favor of PAT; need to include more information on alternatives such as psychotherapy and ketamine-assisted therapy. |

| Content | “Sometimes, afterward, you’re completely knocked out for two weeks, you can’t even leave your house, it’s not the be-all and end-all.” | Warning about the potential for temporary symptom exacerbation following therapy; importance of highlighting possible challenges. |

| Clarity of information | “I would say, the closer you move to the left side, the more this values clarification seems in favor of PAT.” | Confusion regarding the values clarification scale; need to simplify and better contextualize this section. |

| Length | “Everything included in the tool is relevant, there’s nothing superfluous, I think.” | Tool length generally considered appropriate. |

| Most appreciated | “I think the heart of the tool is the values. If there’s one thing to simplify, it’s that. All the other information could be given verbally.” | Values clarification perceived as essential, with suggestions to simplify this section. |

| Theme | Comments | Modifications Made |

|---|---|---|

| Context and structure | Need for better organization of sections to ensure logical progression. | Reorganization of the order of steps: addition of an introductory context, distinction between existential distress, demoralization, and depression. |

| Balance of options | Initial content perceived as too oriented toward psilocybin-assisted therapy. | Inclusion of information about other treatments (psychotherapy, ketamine-assisted therapy, spiritual interventions) to maintain balance. |

| Language and literacy | Language considered too complex by some users. | Simplification of complex terms (“mystical,” “unconscious”); use of accessible and inclusive wording. |

| Psilocybin-assisted therapy | Expectations considered too high and lack of clarity regarding steps and benefits. | Reduction of terms that could inflate expectations, inclusion of medical evaluation steps, simplification of explanations about benefits and risks. |

| Risks and contraindications | Insufficient information provided about certain risks and contraindications. | Addition of specific contraindications (e.g., liver problems, brain injuries) and simplification of the symptom and drug interaction tables. |

| Comparative treatment table | Perceived as too dense and not very visual. | Revision of the table: addition of spiritual interventions, clarification of descriptions, presentation of benefits and risks for each option, inclusion of ketamine therapy. |

| Values clarification scale | Scale perceived as unclear and difficult to use. | Complete revision of the scale, ensuring consistency and providing better contextual information. |

| FAQ section | Need for simplifications and addition of practical information. | Simplification of terminology, addition of advice for consulting a healthcare provider, clarification about the experimental status of the therapy. |

| Documentary resources | Request for easier access to additional information. | Addition of a dedicated section for resources for patients and healthcare professionals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bélanger, A.; Chang, S.-L.; Stephan, J.-F.; Moureaux, F.; Tapp, D.; Foxman, R.; Gagnon, P.; Hébert, J.; Farzin, H.; Dorval, M. Supporting Meaningful Choices: A Decision Aid for Individuals Facing Existential Distress and Considering Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182290

Bélanger A, Chang S-L, Stephan J-F, Moureaux F, Tapp D, Foxman R, Gagnon P, Hébert J, Farzin H, Dorval M. Supporting Meaningful Choices: A Decision Aid for Individuals Facing Existential Distress and Considering Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182290

Chicago/Turabian StyleBélanger, Ariane, Sue-Ling Chang, Jean-François Stephan, Florence Moureaux, Diane Tapp, Robert Foxman, Pierre Gagnon, Johanne Hébert, Houman Farzin, and Michel Dorval. 2025. "Supporting Meaningful Choices: A Decision Aid for Individuals Facing Existential Distress and Considering Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182290

APA StyleBélanger, A., Chang, S.-L., Stephan, J.-F., Moureaux, F., Tapp, D., Foxman, R., Gagnon, P., Hébert, J., Farzin, H., & Dorval, M. (2025). Supporting Meaningful Choices: A Decision Aid for Individuals Facing Existential Distress and Considering Psilocybin-Assisted Therapy. Healthcare, 13(18), 2290. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182290