A Physician-Driven Patient Safety Paradigm: The “Pitfall Bank” as a Translational Mechanism for Medical Error Prevention

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Persistent Challenge of Medical Errors

2. The Prevailing Paradigm: A Critical Analysis of Safety-I

- Failure 1: Unreliable and Incomplete Data

- Failure 2: Inability to Manage Complexity

- Failure 3: Neglect of Human Adaptation and Resilience

3. Alternative Framework: Safety-II and Resilience in Healthcare

- Healthcare as a Complex Adaptive System: Safety-II recognizes that healthcare is not a simple, linear machine but a complex adaptive system characterized by interconnected components, feedback loops, and emergent behaviors. In such systems, safety cannot be secured by controlling parts in isolation; it must be managed by understanding and influencing interactions across the whole system.

- Humans as a Resource for Resilience: While Safety-I treats human variability as a threat, Safety-II treats it as an indispensable resource. No set of rules can anticipate the full range of scenarios clinicians face. The capacity of frontline professionals to adapt, make trade-offs, and improvise in real time enables the system to function effectively despite uncertainty and variability.

- Understanding Work-as-Done: Safety-II distinguishes between “work-as-imagined” (idealized procedures in manuals and protocols) and “work-as-done” (the realities of practice). Safety improvement depends not on stricter enforcement of the imagined model but on a deep understanding of how successful adaptations occur and how they can be supported [14].

- Proactive Capacity Building: Safety-II shifts the goal of safety management from reactive error prevention to proactive capacity enhancement. Rather than focusing solely on rare failures, it seeks to strengthen a system’s ability to anticipate, monitor, respond, and learn, thereby improving overall resilience [16,17].

4. An Untapped Resource: The Prevalence and Distribution of “Pitfalls” in Medical Literature: A PubMed-Based Bibliometric Analysis from 1990 to 2024

4.1. Introduction

4.2. Data Source Selection

4.3. Search Strategy and Execution

4.4. Search Validation and Relevance Confirmation

4.5. Results

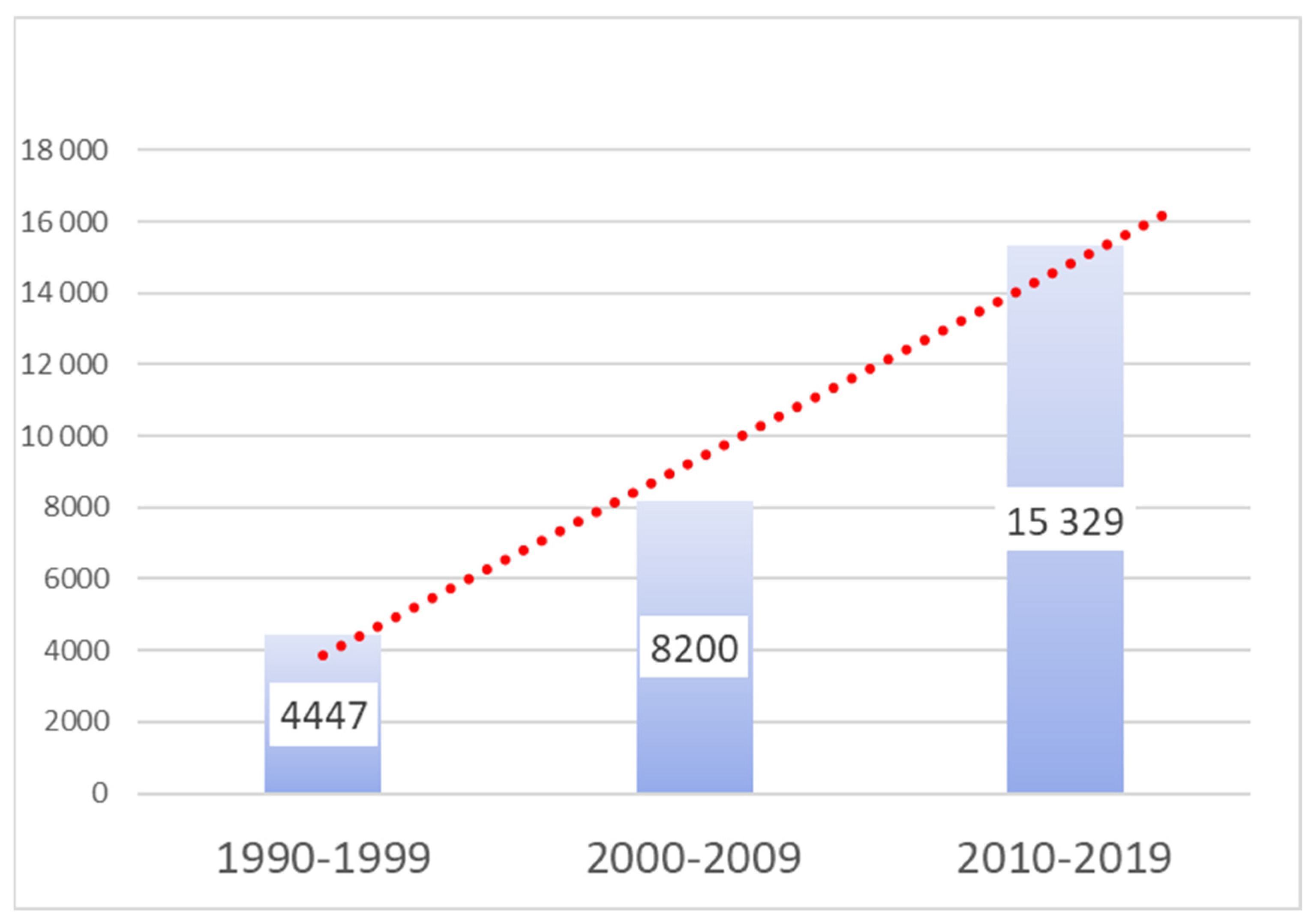

4.6. Overall Publication Volume and Prominence

4.7. Distribution Across Key Medical Specialties

5. A Proposed Solution: The “Pitfall Bank” as a Proactive, Physician-Driven Prevention System

- Overcoming Inaccessibility and Time Constraints: Physicians at the point of care face immense time pressure. Studies indicate that while a comprehensive literature search can take nearly 30 min, most clinicians will abandon a search that lasts longer than two minutes [20]. The Pitfall Bank solves this “no time to search” problem by providing immediate, bedside access to relevant information. A physician facing a challenging diagnostic or therapeutic situation could simply enter the condition or scenario and receive a curated list of the most common pitfalls and the peer-vetted strategies to avoid them. This transforms the current state of being “unwarned and unarmed” against preventable errors into a state of being “forewarned and forearmed”.

- Fostering Collective Experience: Currently, physicians gain crucial experience in recognizing and avoiding pitfalls largely through individual trial and error—a long and often painful process that inevitably involves learning from mistakes that may harm patients. The Pitfall Bank fundamentally changes this dynamic by converting the scattered, individual experiences of thousands of physicians into a concentrated, collective intelligence. It allows a single physician to benefit from the hard-won wisdom of the entire medical community, compressing decades of individual learning curves into readily accessible insights. This accelerates the acquisition of expert-level situational awareness and directly reduces the patient harm that occurs during a clinician’s individual learning journey.

- Reducing Unwarranted Clinical Variation: The well-documented variability in diagnostic and treatment decisions among physicians for identical clinical situations is a significant quality and safety concern. This variation often indicates that, due to the limitations of individual experience, some clinicians may be struggling to identify the optimal path. The Pitfall Bank can serve as a platform for harmonizing best practices in high-risk scenarios. By providing access to a consensus view on how to navigate specific pitfalls, it can help reduce unwarranted variation and guide clinicians toward safer, more effective decisions.

- Bridging the Medical Education Gap: Modern medical education, both in universities and in Continuing Medical Education (CME) programs, largely focuses on teaching the standard methods for diagnosis and treatment. It often fails to systematically warn trainees about common errors and how to avoid them. The Pitfall Bank would serve as an invaluable educational resource, providing structured, practical, experiential knowledge of where things can go wrong. It could be integrated into training programs to better prepare the next generation of physicians for the real-world complexities of clinical practice.

6. The Pitfall Bank as a Translational Medicine Engine

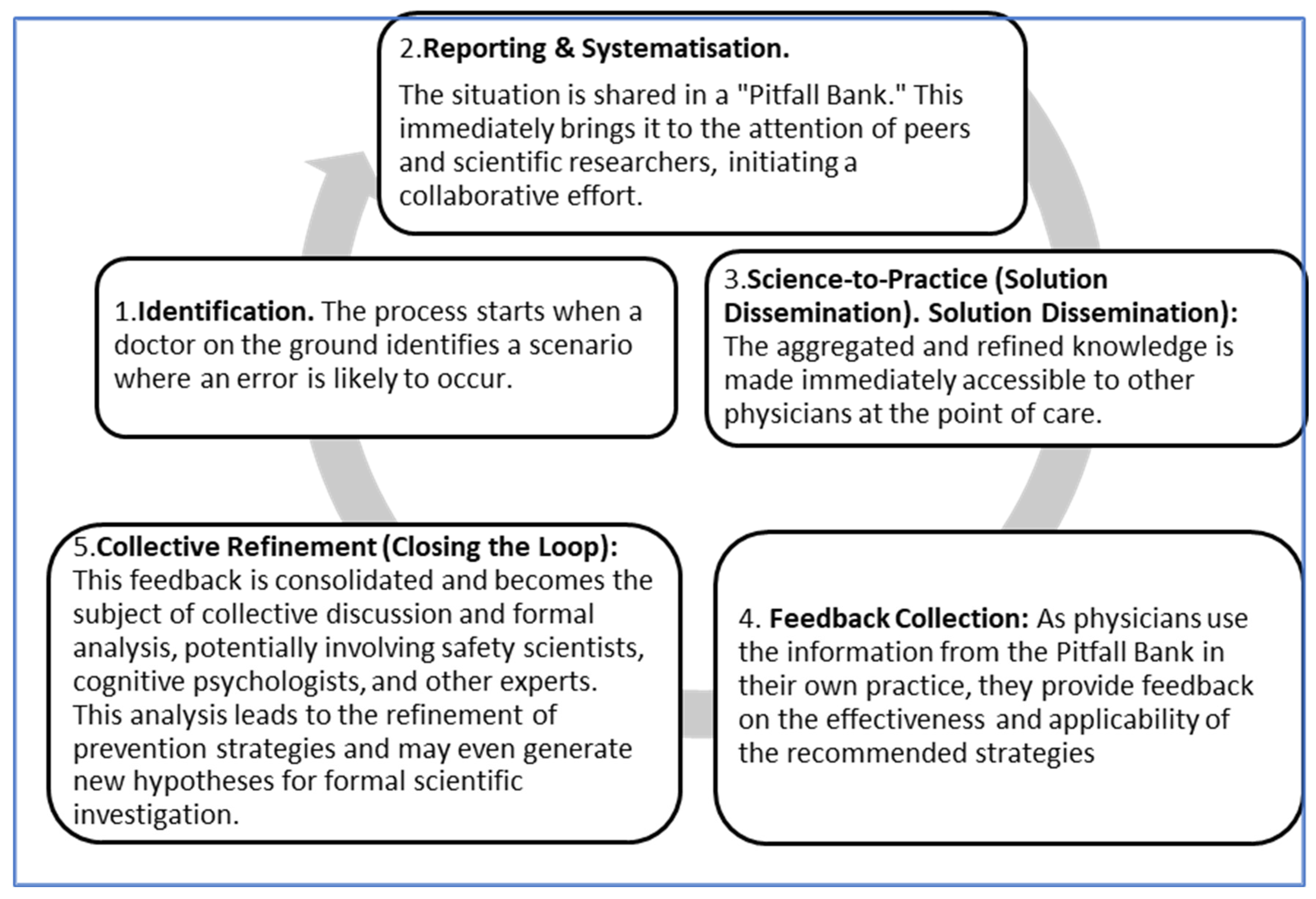

- Identification of a risk-prone situation: The cycle begins with a practicing physician who identifies a high-risk situation or “pitfall” in their daily work. This frontline observation is the “bedside” data. The physician documents this pitfall and the context-specific strategies they used to avoid an error.

- Reporting and Systematization: The physician’s report is submitted to the Pitfall Bank, where it is curated, peer-reviewed, and systematized alongside thousands of other reports. This step transforms isolated anecdotes into a structured, searchable knowledge base.

- Science-to-Practice (Solution Dissemination): The aggregated and refined knowledge is made immediately accessible to other physicians at the point of care. This is the “bench-to-bedside” transfer, where the collective wisdom of the community is delivered as a practical tool to prevent harm.

- Feedback Collection: As physicians use the information from the Pitfall Bank in their own practice, they provide feedback on the effectiveness and applicability of the recommended strategies. This creates a new layer of real-world data on the intervention’s performance.

- Collective Refinement (Closing the Loop): This feedback is consolidated and becomes the subject of collective discussion and formal analysis, potentially involving safety scientists, cognitive psychologists, and other experts. This analysis leads to the refinement of prevention strategies and may even generate new hypotheses for formal scientific investigation. This closes the translational loop, initiating a new cycle of continuous improvement.

7. Discussion

7.1. Principal Findings and Contributions

7.2. Comparison with Existing Systems and Novelty of the Proposed Model

- Reactive vs. Proactive Focus: Existing official databases, such as the FDA’s MedWatch and the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database, are inherently reactive. They catalogue adverse events and device failures after they occur [22,23]. By contrast, the Pitfall Bank is proactive, focusing on identifying and disseminating knowledge about high-risk situations before they result in harm, shifting emphasis from incident analysis to risk anticipation.

- Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up Knowledge Generation: Many safety initiatives, including some physician-led efforts, operate top-down—relying on expert panels to develop guidelines or protocols for specific error types, such as medication administration or surgical procedures [24,25]. While valuable, these approaches fail to capture the full spectrum of frontline experiential knowledge. The Pitfall Bank is inherently bottom-up, driven by the collective, real-world experiences of practicing physicians.

- Static vs. Dynamic Systems: Traditional clinical research databases and case repositories are typically static collections used for retrospective analysis or teaching [26,27]. Similarly, online physician forums, while fostering discussion, are unstructured and lack mechanisms for systematic curation and refinement. The Pitfall Bank is dynamic, functioning as a living system with a continuous translational feedback loop (Figure 2) in which knowledge is submitted, refined through peer feedback, and reintegrated into practice. This circular, self-improving process constitutes its most significant innovation.

7.3. Implications for Policy, Practice, and Economic Viability

7.3.1. Fostering a Just Culture and Enhancing Professional Development

7.3.2. The Economic Imperative: A Return-on-Investment Case for the Pitfall Bank

7.4. Limitations and Future Research

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.M.; Donaldson, M.S. (Eds.) To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Patient Safety. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Department of Health and Social Care (UK). Review of Patient Safety Across the Health and Care Landscape. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-patient-safety-across-the-health-and-care-landscape/review-of-patient-safety-across-the-health-and-care-landscape (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ahsani-Estahbanati, E.; Gordeev, V.S.; Doshmangir, L. Interventions to reduce the incidence of medical error and its financial burden in health care systems: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 875426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iflaifel, M.; Lim, R.; Ryan, K.; Crowley, C. Resilient Health Care: A systematic review of conceptualisations, study methods and factors that develop resilience. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Advancing Patient Safety: A Decade of Evidence, Design, and Implementation. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/advancing-patient-safety.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Russ, S.J.; Rout, S.; Sevdalis, N.; Moorthy, K.; Darzi, A.; Vincent, C. The problem with checklists. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E. Safety-II in Practice: Developing the Resilience Potentials; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Azim, A.; Juergens, M.; Ciobotea, R.; Fudulu, D.P.; Lupu, V.D.; Litschel, R.; Prahm, C. Moving Away from the Blame Culture: The Way Forward to Manage Medical Errors. Medicina 2024, 60, 697. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, C.; Mckie, A.; Turner, M.; Kaak, V. Barriers and facilitators related to the implementation of surgical safety checklists: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollnagel, E. FRAM: The Functional Resonance Analysis Method: Modelling Complex Socio-Technical Systems; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E.; Clay-Williams, R. Work-as-Imagined and Work-as-Done. In Implementation Science: The Key Concepts; Rapport, F., Clay-Williams, R., Braithwaite, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hollnagel, E. Can we ever imagine how work is done? In Hindsight 25; EUROCONTROL: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Glette, M.K.; Ludlow, K.; Wiig, S.; Bates, D.W.; Austin, E.E. Resilience perspective on healthcare professionals’ adaptations to changes and challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-synthesis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, I.; Schuster, A.; Smith, K.; Pronovost, P.; Wu, A. Patient safety incident reporting: A qualitative study of thoughts and perceptions of experts 15 years after ‘To Err is Human’. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post, C.; Ritala, P. Conceptualizing and measuring theoretical contribution. J. Manag. 2020, 48, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, J.W.; Osheroff, J.A.; Chambliss, M.L.; Ebell, M.H.; Rosenbaum, M.E. Answering physicians’ clinical questions: Obstacles and potential solutions. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2005, 12, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, S.H. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA 2008, 299, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. What is MedWatch? FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch-fda-safety-information-and-adverse-event-reporting-program (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Zuckerman, D.M.; Brown, P.; Nissen, S.E. Medical device recalls and the FDA approval process. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Joint Commission. (n.d.). National Patient Safety Goals. Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/ (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Safran, C.; Bloomrosen, M.; Hammond, W.E.; Labkoff, S.; Markel-Fox, S.; Tang, P.C.; Detmer, D.E. Toward a national framework for the secondary use of health data: An American Medical Informatics Association white paper. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2007, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, M.G.; Raebel, M.A.; Glanz, J.M.; Platt, R. A pragmatic framework for single-site and multisite clinical cohort studies. eGEMs 2012, 1, 1036. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, D. Patient Safety and the ‘Just Culture’: A Primer for Health Care Executives; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman, S.; Berwick, D.; Iles, D.; Lewin, L.S.; Davidoff, F.; Nolan, T.; Bisognano, M. The business case for quality: Case studies and an analysis. Health Aff. 2003, 22, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.J.; Phillips, P.P. Show Me the Money: How to Determine the ROI in People, Projects, and Programs; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Savitz, L.A.; Biviji, R.; Franco, T. Making the business case for quality improvement: A framework for calculating return on investment. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2013, 29, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Andel, C.; Davidow, S.L.; Glickman, M.; Kawa, D. The Economic Measurement of Medical Errors; Society of Actuaries: Schaumburg, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bos, J.; Rustagi, K.; Gray, T.; Halford, M.; Ziemkiewicz, E.; Shreve, J. The $17.1 billion problem: The annual cost of measurable medical errors. Health Aff. 2011, 30, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Medical Association. AMA Studies Show Continued Cost Burden of Medical Liability System. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/ama-press-releases/ama-studies-show-continued-cost-burden-medical-liability-system (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Dyer, O. Physician burnout costs US $4.6bn a year, study finds. BMJ 2019, 365, l2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, S. How Much Is Physician Burnout Costing Your Organization? American Medical Association. Available online: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/how-much-physician-burnout-costing-your-organization (accessed on 20 August 2024).

| Dimension | Safety-I | Safety-II |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of Safety | A state where the number of adverse outcomes is as low as possible (freedom from unacceptable harm). | A state where the number of successful outcomes is as high as possible (the ability to succeed under varying conditions). |

| View of Error | Errors are caused by failures of components (technical or human) and represent a deviation from required performance. | Errors are the inevitable downside of normal performance variability; the same adaptations that usually create success can, in certain conditions, lead to failure. |

| Prevention Strategy | Reactive: Find and fix the causes of adverse events. Eliminate or constrain human variability. | Proactive: Understand how everyday work succeeds. Enhance the system’s ability to adapt and be resilient. |

| Role of Clinician | A potential source of error and liability whose performance must be controlled and monitored through rigid protocols. | A critical resource for resilience and safety whose adaptive capacity is necessary for the system to cope with complexity. |

| Application in Healthcare | Top-down administrative mandates (e.g., surgical checklists, CPOE) effective for simple, linear tasks. | Bottom-up, clinician-driven initiatives (e.g., the proposed “Pitfall Bank”) that leverage experiential knowledge for complex, dynamic tasks. |

| Query Component | Search String Example | Field | Rationale/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Term Search (General) | “pitfall” [All Fields] OR “pitfalls” [All Fields] | [All Fields] | To capture any mention of the singular or plural form of the term anywhere in the publication record (including full text where available). |

| Core Term Search (Title) | “pitfall” OR “pitfalls” AND [Title] | [Title] | To identify publications where the discussion of pitfalls is the primary topic, as indicated by its inclusion in the article title. |

| Core Term Search (Title/Abstract) | “pitfall” OR “pitfalls” AND [Title/Abstract]) | [Title/ Abstract]) | To identify publications where pitfalls are a key theme, important enough to be mentioned in the title or the author-supplied summary. |

| Specialty Modifier | “Surgery” [All Fields] | [Specialty] | To filter the specialty. |

| Date Filter | 1 January 1990:28 February 2024 | [pdat] | To limit the search to the defined period of modern medicine, from 1 January 1990 to the end of the last full month before the search date. |

| Medical Specialty | Total Publications with “Pitfall” | Publications with “Pitfall” in Title | Publications with “Pitfall” in Abstract | % of Total with “Pitfall” in Title or Abstract |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | 9960 | 1152 | 1971 | 19.8% |

| Histopathology/Pathology | 8940 | 1661 | 2772 | 31.0% |

| Radiology | 5587 | 694 | 1129 | 20.2% |

| Pediatrics | 2064 | 139 | 249 | 12.1% |

| Internal Medicine | 1339 | 119 | 228 | 17.0% |

| Laboratory Medicine | 1765 | 219 | 389 | 22.0% |

| Anesthesiology | 360 | 15 | 27 | 7.5% |

| Endocrinology | 543 | 47 | 75 | 13.8% |

| Ophthalmology | 277 | 1 | 1 | 0.4% |

| All Specialties | 37,295 | 3044 | 6249 | 16.8% |

| Identified Failure in Current System (Safety-I) | Proposed Solution via “Pitfall Bank” (Safety-II) |

|---|---|

| Lack of Hazard Recognition: Doctors may not recognize that a situation is high-risk, so they fail to take preventive measures. | Targeted Alerts: Physician-driven, context-specific warnings that address knowledge gaps and trigger analytical (System 2) thinking. |

| Siloed Experience: Each physician individually develops their experience in identifying and preventing high-risk situations. This experience is therefore subjective and limited to their personal practice. | Collective Intelligence: Individual experiences are integrated into a collective knowledge base, made easily accessible through the Pitfall Bank. |

| Slow Learning Curve: Acquiring the experience to identify and prevent high-risk situations is a slow process for individual doctors, often requiring years of practice and learning from personal mistakes. | Accelerated Expertise: The collective experience curated by the Pitfall Bank is available to physicians from the beginning of their careers, helping to prevent errors. |

| Unreliable Error Data: A “culture of blame” and fear of litigation lead to the chronic underreporting of adverse events. | Psychological Safety: A non-punitive, educational platform focused on proactive learning from high-risk situations, not reactive reporting of failures. |

| Gap Between Research and Practice: Lack of a functional mechanism to connect frontline problems with scientific solutions. | Translational Feedback Loop: A circular feedback system that systematically bridges the gap between clinical practice and scientific research. |

| Inaccessibility of Knowledge: Experiential knowledge is scattered across thousands of publications, making it unusable at the point of care due to time constraints. | Knowledge at Your Fingertips: A centralized, curated, and instantly searchable repository that delivers relevant, actionable knowledge to the bedside in seconds. |

| Domain of Economic Impact | Current Annual Costs (The Price of Inaction) | Projected Impact of the Pitfall Bank (Return on Investment) | Supporting Evidence and Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Direct Medical Costs of Preventable Adverse Events | USD 17.1–USD 20 billion annually in the U.S. from measurable medical errors. These costs arise from additional care, extended hospitalizations, and managing complications. | Cost-Avoidance: By proactively warning clinicians of high-risk scenarios, the Pitfall Bank reduces the incidence of preventable errors, leading to direct savings from fewer complications, shorter lengths of stay, and reduced need for remedial procedures. | [32,33] |

| 2. Medical Liability and Litigation | Average malpractice indemnity payment exceeds USD 350,000. The average cost to defend a claim, even if dismissed, is >USD 30,000. | Risk Mitigation: The platform serves as evidence of a proactive institutional commitment to safety. By arming physicians with peer-vetted knowledge to avoid common pitfalls, it directly reduces the frequency of negligent errors, thereby lowering the incidence of costly claims and substantial defense expenditures. | [34] |

| 3. Systemic Costs of Physician Burnout and Turnover | USD 4.6 billion annually in national costs attributable to physician burnout. The direct cost to an organization to replace a single physician is USD 500,000–USD 1,000,000+. | Human Capital Preservation: By fostering a non-punitive “just culture” (a Safety-II principle), the Pitfall Bank directly addresses a primary driver of burnout. This improves physician retention, avoiding massive, non-externalizable turnover costs and preserving productivity and institutional knowledge. | [35,36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herold, G.; Justickis, V.; Maneikienė, V.; Maneikis, K.; Trinkauskas, P.; Palkova, K. A Physician-Driven Patient Safety Paradigm: The “Pitfall Bank” as a Translational Mechanism for Medical Error Prevention. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172248

Herold G, Justickis V, Maneikienė V, Maneikis K, Trinkauskas P, Palkova K. A Physician-Driven Patient Safety Paradigm: The “Pitfall Bank” as a Translational Mechanism for Medical Error Prevention. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172248

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerold, Gerd, Viktoras Justickis, Vytė Maneikienė, Kazimieras Maneikis, Paulius Trinkauskas, and Karina Palkova. 2025. "A Physician-Driven Patient Safety Paradigm: The “Pitfall Bank” as a Translational Mechanism for Medical Error Prevention" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172248

APA StyleHerold, G., Justickis, V., Maneikienė, V., Maneikis, K., Trinkauskas, P., & Palkova, K. (2025). A Physician-Driven Patient Safety Paradigm: The “Pitfall Bank” as a Translational Mechanism for Medical Error Prevention. Healthcare, 13(17), 2248. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172248