Self-Management Behaviours in Type 2 Diabetes Across Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: An Updated Narrative Review to Enhance Patient Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

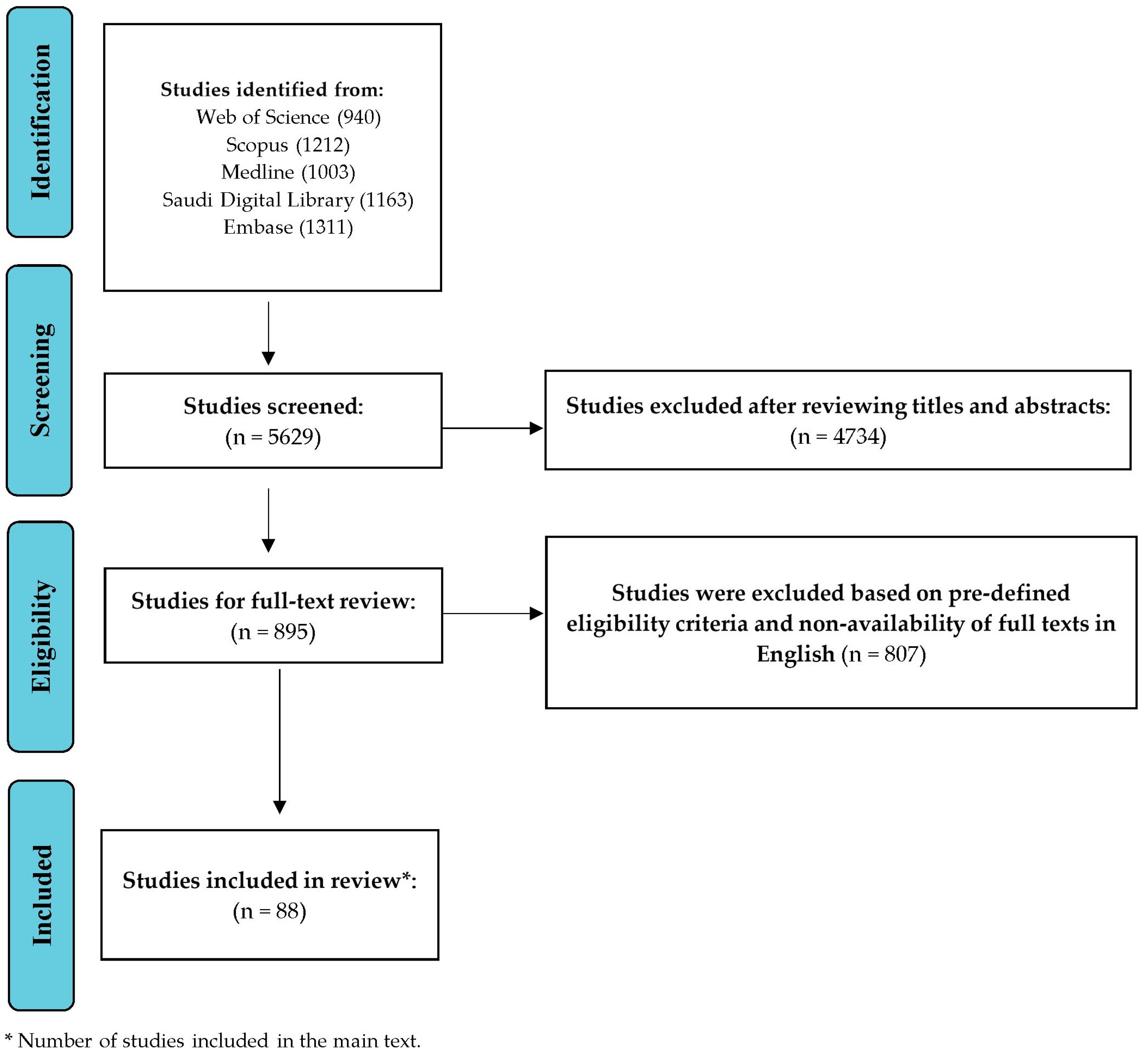

2. Search Strategies

3. Main Findings (Results)

3.1. Patient Practices in Self-Management

3.1.1. Medication Adherence Behaviours

3.1.2. Dietary Pattern Trends

3.1.3. Physical Activity Level

3.1.4. Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose

3.1.5. Other Self-Management Components

3.2. Patient Perspectives, Determinants, and Barriers of Self-Management

3.2.1. Knowledge and Understanding of Diabetes

3.2.2. Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Self-Management

3.2.3. Motivators and Barriers to Effective Self-Management

3.3. Knowledge Gaps

- i.

- Limited research on diverse population subgroups: One of the critical gaps identified in this review is a significant lack of evidence and insufficient representation of diverse patient subgroups. Most research has concentrated on adults at urban tertiary care facilities while neglecting rural citizens, lower-income groups, and foreign nationals. Notably, the GCC region has significant demographic variations, including among expatriate communities.

- ii.

- Fragmented assessment of psychosocial and mental health factors: Some authors have attempted to find the relationship between mental health well-being and self-management practices among T2DM patients. However, these studies are limited, and there is a lack of comprehensive assessment.

- iii.

- Insufficient evaluation of cultural and religious influences: the impact of cultural and religious elements on diabetes self-management in GCC countries has been recognized, but systematic investigations into their effects are lacking.

- iv.

- Gaps in technology adoption and digital health interventions: The vast use of smartphones and internet connectivity in GCC countries creates new opportunities to support diabetes self-management through digital health tools. Studies evaluating the effectiveness, sustainability, and usability of mobile health applications and telemedicine services, wearable glucose monitors, and remote coaching programs are scarce in the GCC region. The majority of current research shows only brief outcomes from pilot tests with weak outcome evaluation methods.

- v.

- Underexplored the role of healthcare system factors: The majority of studies have focused on patient-oriented factors and their association with self-management behaviour. Studies that explore factors related to health systems, including the availability and accessibility of multidisciplinary teams, diabetes educators, continuity care, and referral systems, are limited.

- vi.

- Lack of higher levels of evidence from longitudinal and interventional research designs: most of the existing evidence and conclusions related to self-management behaviour are based on cross-sectional studies, limiting policymakers from drawing strong inferences for implementing necessary changes.

- vii.

- Limited focus on patient-centred outcomes: Research conducted in the GCC region has focused mostly on clinical outcomes such as glycaemic control, complications, etc, with self-management behaviour. However, research studies that explored patient-oriented outcomes through qualitative analysis are limited.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretative Commentary and Implications

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- IDF. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2025. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Aljulifi, M.Z. Prevalence and reasons of increased type 2 diabetes in Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkandari, A.; Alarouj, M.; Elkum, N.; Sharma, P.; Devarajan, S.; Abu-Farha, M.; Al-Mulla, F.; Tuomilehto, J.; Bennakhi, A. Adult Diabetes and Prediabetes Prevalence in Kuwait: Data from the Cross-Sectional Kuwait Diabetes Epidemiology Program. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kebbi, I.M.; Bidikian, N.H.; Hneiny, L.; Nasrallah, M.P. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in the Middle East and North Africa: Challenges and call for action. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 1401–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernawati, U.; Wihastuti, T.A.; Utami, Y.W. Effectiveness of diabetes self-management education (DSME) in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients: Systematic literature review. J. Public. Health Res. 2021, 10, jphr-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, P.M.; Pienaar, M.; Reid, M. Self-management practices for preventing complications of type II diabetes mellitus in low and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2023, 5, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadli. The Impact of Self-Management-Based Care Interventions on Quality of Life in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Philosophical Perspective. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, F.A.; Mohamed, M.S.; Elbur, A.I.; Abdelaziz, S.I.; Elrayah, Z.A. Influence of self-efficacy management on adherence to self-care activities and treatment outcome among diabetes mellitus type 2. Pharm. Pract. 2018, 16, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Jin, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; He, X.; Chen, W.; Gong, N. A Mixed Methods Assessment of Self- Management Needs and Preferences of People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in China. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2023, 17, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, R.; Ackon, S.K.; Kumah, E.; Botchwey, C.O.-A.; Appiah, N.E.; Korsah, S.; Peprah, M. Self-care behaviors and associated factors among individuals with type 2 diabetes in Ghana: A systematic review. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, M.D.; Malabu, U.H.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. Enablers and barriers to effective diabetes self-management: A multi-national investigation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochani, R.K.; Shaikh, A.; Batra, S.; Pikale, G.; Surani, S. Diabetes among Muslims during Ramadan: A narrative review. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 6031–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japar, S.; Ong, S.L.; Muhamed, Z.; Fukunaga, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Imachi, H.; Sato, S.; Saheki, T.; Ibata, T.; Yoshimura, T.; et al. Knowledge of diabetes and the practice of diabetes self-management during Ramadan fasting among patients with type 2 diabetes in Malaysia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.A.; Alsiary, K.A.; Khan, M.A.; Bushnaq, A.; Alzahrani, B.; Salama, M.; Alamri, N.S. Perception of herbs use in treating diabetes among patients attending specialized polyclinics of National Guard Health Affairs, Jeddah. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2023, 12, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi Soola, A.; Davari, M.; Rezakhani Moghaddam, H. Determining the Predictors of Self-Management Behaviors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: An Application of Socio-Ecological Approach. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 820238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Guo, X.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Du, Y. A Qualitative Exploration of Self-Management Behaviors and Influencing Factors in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 771293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhael, E.M.; Hassali, M.A.; Hussain, S.A.; Shawky, N. Self-management knowledge and practice of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Baghdad, Iraq: A qualitative study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheq, A.; Ashames, A.; Al-Tabakha, M.; Hassan, N.; Jairoun, A. Medication adherence in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients during Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study from the United Arab Emirates. F1000Research 2021, 10, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloudah, N.M.; Scott, N.W.; Aljadhey, H.S.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Alrubeaan, K.A.; Watson, M.C. Medication adherence among patients with Type 2 diabetes: A mixed methods study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfulayw, M.R.; Almansour, R.A.; Aljamri, S.K.; Ghawas, A.H.; Alhussain, S.S.; Althumairi, A.A.; Almuthaffar, A.A.; Alhuwayji, K.A.; Almajed, A.A.; Al-Yateem, S.S.; et al. Factors Contributing to Noncompliance with Diabetic Medications and Lifestyle Modifications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e31965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.A.A.; Kumari, J.; Bahmanshiri, Y. Assessing the Adherence to Antidiabetic Medications Among Patients Diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Ajman, UAE. Cureus 2023, 15, e49325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Ubaidi, B.A.A.; Abdulla, K.J.; Al Jenaidi, N.A.; Ali, H.A.; Marhoon, E.M.; Matar, H.M.; Shakeeb, H.A. Self-Care Management and Glycemic Control Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in Bahrain: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Diabetol. 2024, 13, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.C.; Sreedharan, J.; Satish, K.P.; Ibrahim, H. Health literacy in a high income Arab country: A nation-wide cross-sectional survey study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaham, K.K.; Feyasa, M.B.; Govender, R.D.; Musa, A.M.A.; AlKaabi, A.J.; ElBarazi, I.; AlSheryani, S.D.; Al Falasi, R.J.; Khan, M.A.B. Medication Adherence Among Patients with Multimorbidity in the United Arab Emirates. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 1187–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRuthia, Y.; Aldallal, S.; Al-Abdulkarim, H.A.; Al-Jedai, A.; Almudaiheem, H.; Hamad, A.; Elmusharaf, K.; Saadi, M.; Al Awar, H.; Al Sabbah, H.; et al. Healthcare systems and health economics in GCC countries: Informing decision-makers from the perspective of the Gulf health economics association. Front. Public. Health 2025, 13, 1510401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Aamir, A.H.; Feroz Amin, M.; Bunnag, P.; Chan, S.P.; Guo, L.; Khamseh, M.E.; Mohan, V.; Nicodemus, N.; Roberts, A.; et al. Barriers to the Use of Insulin Therapy and Potential Solutions: A Narrative Review of Perspectives from the Asia–Pacific Region. Diabetes Ther. 2024, 15, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Kim, N.H.; Ku, B.J.; Shon, H.S.; Kim, D.M.; Park, T.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, I.J.; Choi, D.S. Delay of insulin initiation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with oral hypoglycemic agents (analysis of patient- and physician-related factors): A prospective observational DIPP-FACTOR study in Korea. J. Diabetes Investig. 2017, 8, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Al-Qarni, A.A.; Al-Jamaan, M. Dietary carbohydrate intake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetes control: A cross-sectional study. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 64, 10–29219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, O.M.; Alhomaid, T.A.; Alshuaibi, A.M.; Ahmad Alahmad, R.M.; Al Mardhamah, N.H.; Alamri, T. The Influence of Eating Habits on Type 2 Diabetes in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e42638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaradi, M.; Ouagueni, A.; Khatib, R.; Attieh, G.; Bawadi, H.; Shi, Z. Dietary patterns and glycaemic control among Qatari adults with type 2 diabetes. Public. Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4506–4513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzaz, Z.J.; Baig, M.; Kanpurwala, M.A.; Jamil, T.; Mojaddidi, M.A.; Murad, M.A. Eid-al-Fitr festivity and Ramadan fasting attitude among individuals with diabetes from Saudi Arabia and Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e054902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, M.M.; Hanif, W.; Malek, R.; Jabbar, A. Changes in fasting patterns during Ramadan, and associated clinical outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: A narrative review of epidemiological studies over the last 20 years. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 172, 108584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ozairi, A.; Taghadom, E.; Irshad, M.; Al-Ozairi, E. Association Between Depression, Diabetes Self-Care Activity and Glycemic Control in an Arab Population with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023, 16, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayed, A.; AlRadini, F.; Alzuhairi, R.M.; Aljuhani, A.E.; Alrashid, H.R.; Alwazae, M.M.; Alghamdi, N.R. Relation between diabetes related distress and glycemic control: The mediating effect of adherence to treatment. Prim. Care Diabetes 2022, 16, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfetni, A.; Alqahtani, M.; Alhumaid, A.; Alhazmi, A.; Alqahtani, B.; Alghamdi, K.; Alsaedi, Z.; Alsulaimani, W.; Alqurashi, R.; Binhumaid, A. Physical activity prevalence and barriers among type 2 diabetic patients, Kudai and Al-hijra primary health care center, Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Med. Sci. 2022, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheeday, A.M.; Alshammari, H.S.; Alshammari, B.; Alkubati, S.A.; Llego, J.H.; Alshammari, A.D.; Alshammari, M.H.; Almohammed, R.A.; Alsheeb, S.M.S.; Alshammari, F. Perceived Barriers to Healthy Lifestyle Adherence and Associated Factors Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Implications for Improved Self-Care. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 2425–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momani, A.; Al-Marzouqi, Z.; Abu-Shhadeh, A.; Ajlouni, K.; AlBashtawy, M.; Almomani, M.H.; Jarrah, S.; AlQahtani, S.A.; Ababneh, A. Physical activity among adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Jordan: A qualitative study. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 16, 20420188251315658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadi, F.; Abusnana, S.; Afandi, B.; Aldahmani, K.M.; Alhajeri, O.; Aljaberi, K.; Alkaabi, J.; Almadani, A.; Bashier, A.; Beshyah, S.A. Emirates diabetes society consensus guidelines for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus–2020. Dubai Diabetes Endocrinol. J. 2020, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, A.; Tharkar, S.; Babaier, W.S.; Alsomali, S.F.; Alsulayhim, A.S.; Alayuni, M.A.; Aldakheel, N.A.; Al-Osaimi, S.S.; Alshehri, N.; Batais, M. Blood Glucose Monitoring and Sharing Amongst People with Diabetes and Their Facilitators: Cross-sectional Study of Methods and Practices. JMIR Diabetes 2021, 6, e29178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meer, Z.; Al-Ozairi, E.; Fernandes, G.; Ranganathan, S.; Patel, J. Information behaviours of people with type 2 diabetes in Kuwait: A grounded theory study. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlRasheed, A.Y.; Hashim, H.; Alrofaie, H. Adherence to Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose and Its Related Factors Among Type 2 Diabetic Patients Attending Al-Ahsa Primary Health Care Centers in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e65545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhormi, A.H.; Mahfouz, M.S.; Alshahrani, N.Z.; Hummadi, A.; Hakami, W.A.; Alattas, D.H.; Alhafaf, H.Q.; Kardly, L.E.; Mashhoor, M.A. Psychological Health and Diabetes Self-Management among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes during COVID-19 in the Southwest of Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2022, 58, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, S.M.; Alamer, A.; Albaggal, A.; Alsuwaiket, M.; Alotaibi, F.M.; Asiri, I.M.; Alshayban, D.M.; Alsultan, M.M.; Alshehail, B.; Almalki, B.A.; et al. The Association between Self-Care Activities and Depression in Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Hafidh, K.; Saidawi, W.; Othman, A.M.; Khakpour, M.M.; Zoghbor, M.M.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Shaw, J.E. Behavioral, psychological, and clinical outcomes of Arabic-speaking people with type 2 diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic. Prim. Care Diabetes 2022, 16, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsumry, S.H.; Al Ghelani, T.; Jaju, S. Depression in Urban Omani Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2022, 22, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobani, M.A.; Khusheim, L.H.; Fadel, B.A.; Dammas, S.; Kattan, W.M.; Alyousef, M.S. Barriers to Access and Utilization of Diabetes Care Among Patients with Severe Mental Illness in Saudi Arabia: A Qualitative Interpretive Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyamani, R.; Naja, S.; Al-Dahshan, A.; Hamoud, H.; Bougmiza, M.I.; Alkubaisi, N. Mental health literacy in Arab states of the Gulf Cooperation Council: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, A.; Akin, S.; Kundakci, N. Self-esteem mediates the relationship perceived stigma with self-efficacy for diabetes management in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Saudi Med. J. 2022, 43, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, R.I.; Allah, A.A.; Mubarak, A.S.; Abdullah, R.I.; Alzhrani, S.H.; Alsufyani, M.H.; Alharthi, S.J.A.; Althomali, R.O.H. Prevalence and predictors of using complementary and alternative medicine among diabetic patients in Taif city, Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 2092–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, H.; Hasan, H.; Hamadeh, R.; Hashim, M.; AbdulWahid, Z.; Hassanzadeh Gerashi, M.; Al Hilali, M.; Naja, F. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with type 2 diabetes living in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, F.M.; AlBassam, K.S.; Alsairafi, Z.K.; Naser, A.Y. Knowledge and practice of foot self-care among patients with diabetes attending primary healthcare centres in Kuwait: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Z.; Al-Natour, M.; Al Rahbi, H. Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy Among Individuals with Diabetes in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Oman Med. J. 2024, 39, e585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, A.; Almulhim, A.K.; Albalawi, F.A.; Alruwaili, Z.M.; Almajed, O.A.; Alruwaili, S.H.; Almugharriq, M.M.; Alruwaili, A.S.; Alkuwaykibi, M.K. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices towards Diabetic Retinopathy among Primary Care Physicians of Saudi Arabia: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredouani, A. Greater and More Focused Measures Are Needed to Tackle Diabetes and Obesity Epidemics in the Nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 2021, 6661346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkalash, S.H.; Alnashri, F.H.; Alnashri, A.I.; Alghubayshi, K.A.; Alsumaydi, M.A.; Alzubaidi, W.S.; Alshuqayfi, S.M.; Alkudaysi, F.M.; Qusty, N.F. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Adult Diabetics Regarding Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e53356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaidan, A.A.; Thirunavukkarasu, A.; Alhassan, H.H.; Bin Ahmed, I.A.; Alnasiri, A.S.; Alhirsan, W.M.; Alazmi, N.N.M.; Alkhlaf, A.K.; Alderbas, J.M.; Alkhaldi, M.A. Evaluation of Self-Management Behaviors and Its Correlation with the Metabolic Syndrome among the Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients of Northern Saudi Arabia. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, S.H.; Waheed, A.S.; Ali, N.A.; AlNajem, N.J.; Abdulrahman, R.M.; Hasan, Z.J. Assessment of Type 2 Diabetes Awareness and Knowledge in the Non-medical Bahraini Population. Cureus 2023, 15, e44231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, M.; Husain, Z.S.M.; Abdouli, K.A.; Kazim, M.N.; Sayed Mahdi Ahmad, F.; Carrick, F.R. Association between knowledge, awareness, and practice of patients with type 2 diabetes with socio-economic status, adherence to medication and disease complications. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 2020, 163, 108124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaidan, A.A.; Alotaibi, S.F.; Thirunavukkarasu, A.; Alruwaili, B.F.; Alharbi, R.H.; Arnous, M.M.; Alsaidan, O.A.; Alduraywish, A.S.; Alwushayh, Y.A. Medication Adherence and Its Associated Factors among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Attending Primary Health Centers of Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2023, 59, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, J.S.; Almigbal, T.H.; Alruhaim, H.Y.; Mujammami, M.H.; AlMogbel, T.A.; Alshahrani, A.M.; Al Zahrani, A.M.; Batais, M.A.; Shaik, S.A. Self-awareness of HbA1c and its association with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes: A multicenter study. Saudi Med. J. 2022, 43, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrasheedi, A.A.; Alqesair, M.H.; Aljurbua, H.F.; Alfanoud, G.A.; Almakrami, M.H.; Mohammad, J.E.J. Knowledge of Complications of Diabetes Mellitus Among Patients Visiting the Diabetes Clinics: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Qassim Region. Cureus 2023, 15, e49896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaidan, A.A.; Alanazi, M.I.; Thirunavukkarasu, A. Assessment of Diabetes-Related Knowledge and Dietary Patterns Among Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Central Saudi Arabia: Insights for Tailored Health Education Strategies. Healthcare 2025, 13, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Razooqi, H.; AlNajjar, B.; AlShamsi, E.; Ibrahim, K.; Sharief, W.; Khansaheb, H.; Zidan, M. Correlation between Glycated Hemoglobin Levels and Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Type 2 Diabetic Patients Attending Primary Health Care Centers in Dubai Health Authority. Dubai Med. J. 2023, 6, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.O.; Sulaiman, A.A. Foot care knowledge, attitude and practices of diabetic patients: A survey in Diabetes health care facility. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 3816–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansy, W.; Wajid, S.; Alwhaibi, A.; Alghadeer, S.M.; Alhossan, A.; Babelghaith, S.; Alrabiah, Z.; Al Arifi, M.N. Assessing Outpatients’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Toward Managing Diabetes in Saudi Arabia. Inquiry 2022, 59, 00469580221082781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhuwais, M.; Alkanderi, A.; Jospeh, B. Attitudes and awareness of diabetic patients in Kuwait towards their oral health. Int. J. Oral. Dent. Health 2021, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almheiri, A.; Binjab, E.A.; Albloushi, M.M.; Alshamsi, M.T.; Khansaheb, H.H.; Zidan, M.; Hassoun, A.A.K. Knowledge, attitude and practices of insulin therapy among patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e079693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsareii, S.A. Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Foot Self-Care among Diabetic Patients Attending Different Diabetic Clinics in Najran, Saudi Arabia. King Khalid Univ. J. Health Sci. 2023, 8, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rifai, L.A.; Soubra, L.; Hassanein, M.; Amin, M.E.K. Comprehensive care for patients with diabetes in Ramadan: A module for pharmacy students and pharmacists. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsunni, A.A.; Albaker, W.I.; Almansour, A.H.; Alenazi, A.S.; Alaftan, M.S.; Badar, A. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Regarding Ramadan Fasting and Related Determinants in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes at a Saudi Diabetes Clinic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasasimah, W.A.; Alsabaani, A. Predictors of Diabetes Self-Management Behaviour Among Type 2 Diabetics in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 2371–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerari, A. Contribution of Disease-Specific Distress, Social Support, and Self-Efficacy to Diabetes Self-Management Behaviors in Saudi Adults: A Path Analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 3991–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayed Hassan, D.; Helaluddin, F.; Chahestani, O.H.; Mohamed, O.; Islam, N. Diabetes Self-Management and Health-Related Quality of Life among Primary Care Patients with Diabetes in Qatar: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, F.; Gay, V.; Alturki, R. Poor Compliance of Diabetic Patients with AI-Enabled E-Health Self-Care Management in Saudi Arabia. Information 2022, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzghaibi, H. Barriers to the Utilization of mHealth Applications in Saudi Arabia: Insights from Patients with Chronic Diseases. Healthcare 2025, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-alrazaq, A.A.; Suleiman, N.; Baagar, K.; Jandali, N.; Alhuwail, D.; Abdalhakam, I.; Shahbal, S.; Abou-Samra, A.-B.; Househ, M. Patients and healthcare workers experience with a mobile application for self-management of diabetes in Qatar: A qualitative study. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2021, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrhim, S.; Sankaralingam, S.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Diab, M.I.; Hussain, M.A.M.; Al Raey, H.; Ismail, M.T.; Awaisu, A. Collaborative care model for diabetes in primary care settings in Qatar: A qualitative exploration among healthcare professionals and patients who experienced the service. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Musameh, S. The Effect of Detailed Counseling on the Glycemic Index of Diabetic Patients. Bahrain Med. Bull. 2020, 42, 244–246. [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi, M.M.N.; Alanazi, A.M.N.; Alshammari, A.A.H.; Alshammari, A.A.B.; Nazzal, M.M.A.; Alanazi, D.M.M.; Alanazi, F.M.M. Investigating the Barriers and Facilitators to Effective Patient Education in Saudi Arabian Healthcare Settings: Perspectives of Nursing Professionals, Health Assistants, and Health Administrators. J. Int. Crisis Risk Commun. Res. 2024, 7, 1898. [Google Scholar]

- Alawainati, M.A.; Ayoob, Z.A.; Naser, H.S. Characteristics, glycemic control and outcomes of adults with type-2 diabetes mellitus attending specialized clinics in primary healthcare centers in Bahrain-A cross-sectional study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2023, 12, 2576–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qahtani, A.M. Frequency and factors associated with inadequate self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Najran, Saudi Arabia. Based on diabetes self-management questionnaire. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alodhayani, A.; Almutairi, K.M.; Vinluan, J.M.; Almigbal, T.H.; Alonazi, W.B.; Ali Batais, M.; Mohammed Alnassar, M. Association between self-care management practices and glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Saud Arabia: A cross –sectional study. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2460–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruhaim, H.Y.; Almigbal, T.H.; Almutairi, J.S.; Mujammami, M.H.; AlMogbel, T.A.; Alrasheed, A.A.; Al Zahrani, A.M.; Batais, M.A. The association between diabetes numeracy and diabetes self-management among Saudi adults with insulin-treated diabetes. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BA, A.L.; Alhalal, E.A. Effects of health literacy on type 2 diabetic patients’ glycemic control, self-management, and quality of life. Saudi Med. J. 2022, 43, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, A.A.; Al Awad, A.D.; Al Dawish, M.A. Current Status of Knowledge and Awareness of Diabetes Mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2021, 17, e101220186818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutawaa, K.A.; Farghaly, A.H.; Nasir, R.; Loares, A.M.; Skaroni, I.; Al-Thani, M.; Abou-Samra, A.B. Level of knowledge, attitude and practice towards diabetes among nationals and long-term residents of Qatar: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e052607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Mohamed, H.; Lowe, T.; Khraim, F.; Wolsey, C.; Haque, S.; Al-Farsi, A.; Schnurman, D.; Chowdhury, N.; Raihan, M.M.H.; et al. Addressing the effectiveness of health literacy programs within the Gulf Corporation Council: An integrative review. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belete, A.M.; Gemeda, B.N.; Akalu, T.Y.; Aynalem, Y.A.; Shiferaw, W.S. What is the effect of mobile phone text message reminders on medication adherence among adult type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Tu, Y.Z.; Chiou, H.Y.; Lai, K.; Yu, N.C. Real-world Benefits of Diabetes Management App Use and Self-monitoring of Blood Glucose on Glycemic Control: Retrospective Analyses. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e31764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, N.; Tenev, V.; Kamusheva, M.; Petrova, G. Diabetes Mellitus—Digital Solutions to Improve Medication Adherence: Scoping Review. Diabetology 2023, 4, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company-Bezares, F.; Aretio-Pousa, A. mHealth strategies to improve pharmacologic adherence in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: Systematic review. Farm. Hosp. 2022, 46, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Al Slamah, T.; Nicholl, B.I.; Alslail, F.Y.; Harris, L.; Melville, C.A.; Kinnear, D. Cultural adaptation of self-management of type 2 diabetes in Saudi Arabia (qualitative study). PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, T.A.F.; Alhumaidi, B.; Alharbi, M.N.; Ngo, A.D.; Alasqah, I.; Alharbi, H.F.; Albagawi, B. Diabetes education self-management intervention in improving self-efficacy for people with type 2 diabetes in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2023, 17, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.I.; Al Ketbi, L.B.; Platat, C.; Abdl El Baki, H.; Elmi, F.; Ibrahim, W.; Zoubeidi, T.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Tariq, M.N.M.; et al. Impact of Skills for Change Program on metabolic control, diet and physical activity levels in adults with type 2 diabetes: A cluster randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, O.; Al Sifri, S.; Hassanein, M.; Al Dawish, M.; Al-Dahash, R.A.; Alawadi, F.; Jarrah, N.; Ballout, H.; Hegazi, R.; Amin, A.; et al. The Transcultural Diabetes Nutrition Algorithm: A Middle Eastern Version. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 899393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, M.; Wu, T.; Rayner, C.K.; Marathe, C.S.; Jones, K.L. Spontaneous or Deliberate: Effects of Acute Variations in Glycemia on Gastric Emptying in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrilakis, K.; Kalpourtzi, N.; Ioannidis, I.; Iraklianou, S.; Raptis, A.; Sotiropoulos, A.; Gavana, M.; Vantarakis, A.; Kantzanou, M.; Hadjichristodoulou, C.; et al. Prevalence of diabetes and pre-diabetes in Greece. Results of the First National Survey of Morbidity and Risk Factors (EMENO) study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 172, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.; Ageely, H.; Mahfouz, M.S.; Hummadi, A.A.; Darraj, H.; Solan, Y.; Allan, R.; Bahsan, F.; Hafaf, H.A.; Abohadash, A.; et al. Effects of a Home-Based Physical Activity Program on Blood Biomarkers and Health-Related Quality of Life Indices in Saudi Arabian Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Life 2023, 13, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrismas, B.C.R.; Majed, L.; Al-Mohannadi, A.S.; Sayegh, S. Adherence and retention to the self-managed community-based Step into Health program in Qatar (2012–2019). Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 927386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, N.; Cox, L.; Fraihat, B.; Alzeq, T.K.; Abdalla, M.; Khattabi, N. Patient and Clinician Perspectives on Communication in Primary Care Centres in Qatar-A Focus Group Study. Health Expect. 2025, 28, e70280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlOsaimi, H.M.; Kanan, M.; AlOtaibi, M.; Alhejaili, S.; Alshammari, B.; Khalaf, A.; Hajea, A.; Saleh, R.; Jamal, F.; AbuShahin, A.; et al. Assessing intention to use mobile phone-based self-management support among adults with type 2 diabetes in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Digit. Health 2025, 11, 20552076241308993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xie, N.; Chen, F.; Song, Z.; Zhao, S. Effectiveness of Digital Diabetes Management Technology on Blood Glucose in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes at Home: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e66441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grady, M.; Holt, E.; Cameron, H.; Edelman, S. Improved glycemic outcomes in people with type 2 diabetes using smart blood glucose monitoring integrated with popular digital health therapeutics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Castor, L.; O’Hearn, M.; Cudhea, F.; Miller, V.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J.; Sharib, J.R.; Cash, S.B.; Barquera, S.; Micha, R.; et al. Burdens of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease attributable to sugar-sweetened beverages in 184 countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Databases Searched | Web of Science, Scopus, Medline, Saudi Digital Library, Embase |

| Rationale for Database Selection | Selected for accessibility, coverage, and relevance to T2DM self-management in GCC countries |

| Search Period | January 2020–March 2025 |

| Search Terms/Keywords | (“type 2 diabetes” OR T2DM) AND (“self-management” OR “self-care”) AND (barriers OR facilitators) AND (Saudi Arabia OR Qatar OR UAE OR Kuwait OR Oman OR Bahrain) |

| Boolean Operators Used | “AND”, “OR”, “NOT” |

| Inclusion Criteria | Studies on adult (≥18 years) T2DM patients, peer-reviewed, English language, with DOI, published between January 2020 and March 2025 |

| Exclusion Criteria | Studies on type 1 or gestational diabetes, grey literature, unpublished works and studies not focused on T2DM self-management |

| Screening Method | Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts; discrepancies were resolved with a third reviewer |

| Number of Articles Included | 80 articles |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thirunavukkarasu, A.; Alsaidan, A.A. Self-Management Behaviours in Type 2 Diabetes Across Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: An Updated Narrative Review to Enhance Patient Care. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172247

Thirunavukkarasu A, Alsaidan AA. Self-Management Behaviours in Type 2 Diabetes Across Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: An Updated Narrative Review to Enhance Patient Care. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172247

Chicago/Turabian StyleThirunavukkarasu, Ashokkumar, and Aseel Awad Alsaidan. 2025. "Self-Management Behaviours in Type 2 Diabetes Across Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: An Updated Narrative Review to Enhance Patient Care" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172247

APA StyleThirunavukkarasu, A., & Alsaidan, A. A. (2025). Self-Management Behaviours in Type 2 Diabetes Across Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: An Updated Narrative Review to Enhance Patient Care. Healthcare, 13(17), 2247. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172247