1. Introduction

Self-assessment of quality of life is increasingly used in medicine and otorhinolaryngology and has become an important indicator of treatment success [

1,

2]. Quality of life (QoL) is not easy to define as it encompasses various aspects of one’s life. The literature provides various definitions. The World Health Organization defines it as a patient’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns [

3]. Health-related QoL assesses the impact of an illness on the physical, emotional, and social well-being of patients [

2]. It can also be defined as the possibility that after the treatment is completed, the patient lives physically, mentally, and socially as closely as possible to life before treatment [

3]. Considering the subjective nature of QoL assessment, there are various questionnaires for its measurement globally, one of which is the SF-36 questionnaire used in this study. According to Ware, the author of the questionnaire, health is measured multidimensionally, and therefore, overall quality of life is evaluated through physical health, perceived physical pain, and an individual’s social and emotional state, additionally assessing their mental health [

4]. Physical pain and a consequent decrease in physical health, measured in the questionnaire by their impact on performing daily activities, indicate their significant role in most aspects of an individual’s life and consequently the social and emotional well-being of patients, as a decrease in the performance of daily activities often has a detrimental effect on mental health, and vice versa [

4].

This study aims to evaluate the self-assessed quality of life in groups of otorhinolaryngology (ENT) patients with various conditions and provide more comprehensive insight into their specific healthcare needs. Studies currently present in the literature investigated individual diagnoses and their impact on the QoL in patients, whereas the goal of our study is to provide a comprehensive overview of the QoL of patients in different diagnostic categories in otorhinolaryngology [

5,

6,

7]. We hypothesize that there are significant differences in the self-assessed QoL of patients in different diagnostic categories in the field of otorhinolaryngology. Our hope is to draw attention to tailoring patient communication and treatment based on the current differences in QoL in the hopes of enhancing patient satisfaction and, consequently, their QoL.

The aim of this research is to determine the differences in the self-assessed quality of life among ENT patients in different diagnostic categories, specifically through indicators of physical health, experienced physical pain, and their social and emotional well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

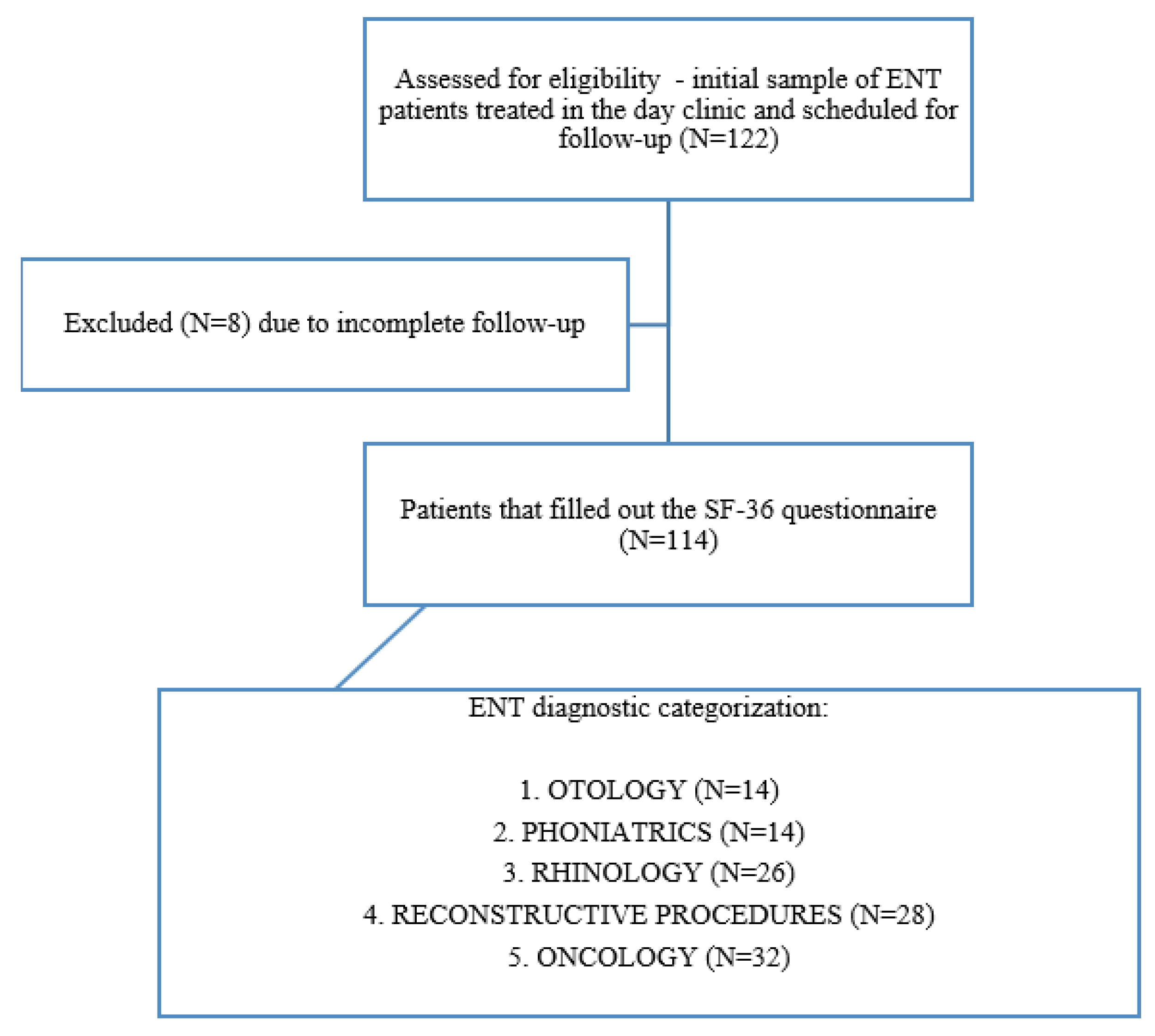

This observational study was conducted according to STROBE guidelines. The details of the patient selection process are provided in

Figure 1.

A convenient sample of respondents was used. The research was an observational cross-sectional study aimed at assessing baseline QoL in different groups of ENT diagnoses prior to any surgical treatment carried out from 1 May to 30 June 2024. The study was designed to include patients coming to the ENT day clinic at the same time during the day who stayed in the same waiting space, were seen by the same ENT team, and were cared for by the same team of nurses and physician assistants. Every attempt was made to afford all respondents equal time to fill out the questionnaire. Inclusion criteria consisted of patients aged 18 and above that had a previously established ENT diagnosis, were scheduled for a follow-up examination at the day clinic, and had completed the survey, alongside providing informed consent. A total of 122 patients participated in this study. Exclusion criteria were failure to complete the survey and the inability to secure informed consent. In addition, patients with multiple diagnoses were excluded to minimize selection bias, as were patients that received any prior surgical treatment to minimize bias related to the effect of surgery or placebo-related effects. Overall, eight respondents were excluded from the study because they did not fill out the information about ENT diagnoses, and the final research sample consisted of 114 patients.

Upon arrival at the follow-up appointment, patients were informed that the research was being conducted, and by signing a written informed consent form, they voluntarily agreed to participate. The study was approved by the University Hospital Center Ethics Committee (No. 251-29-11-24-03).

According to the diagnosis group criterion, the patients were divided into 4 groups according to the current International Classification of Diseases (ICD):

- 1.

OTOLOGY (diseases of the ear)

H60–H95 (diseases of the ear and mastoid processes).

The main grouping criterion was the fact that these diseases affect hearing and communication and are not characterized by pain or physical disability.

- 2.

PHONIATRICS (voice disorders)

J38–J38.3 (diseases of the vocal cords);

R49 (voice disorders).

The main grouping criterion was the fact that these diseases affect voice quality and communication and are not characterized by pain or physical disability.

- 3.

RHINOLOGY (nose and breathing diseases)

J30–J33.9 (diseases of the upper respiratory system, which include vasomotor, allergic, acute, and chronic diseases of the nose and sinuses with or without the presence of polyps).

The main grouping criterion was the presence of chronic nasal inflammation and allergies that primarily affect nasal breathing, chronic stress, and sleep quality and are not marked by significant pain or disability.

- 4.

CONDITIONS THAT REQUIRE RECONSTRUCTIVE PROCEDURES

J34.2 (deviation of nasal septum and nasal pyramid);

J35 (chronic tonsillitis);

D21 (benign connective tissue neoplasms);

Q17.5 (congenital ear malformations: protruding ear);

H02.3 (blepharochalasia).

The main grouping criterion was the absence of any prior surgery or functional deficit and a primarily aesthetic concern in various ENT areas. This group was referred for a follow-up exam due to the absence of any inflammatory disease or functional difficulty, such as nasal tip or pyramid deformity in the J34.2 group or patients concerned with palatine tonsil size or halitosis in the J35 group. The study also included patients with protruding ears in the Q17.5 group and patients referred for possible upper eyelid reduction that did not impair vision to a significant extent in the H02.3 group.

- 5.

ONCOLOGICAL DISEASES OF THE HEAD AND NECK

C00–C14 (malignant neoplasms of the lip, oral cavity and pharynx);

C30–C34 (malignant neoplasms in the respiratory system);

C73 (malignant neoplasm of the thyroid gland);

C43–C44.3 (malignant neoplasm of the skin);

D38.5 (neoplasm of uncertain or unknown behavior of other respiratory organs).

The main grouping criterion was a previously diagnosed malignant disease in the ENT area but prior to any surgery that might affect QoL. These patients were referred for a follow-up examination to discuss further treatment, revise existing recommendations, or schedule diagnostic procedures.

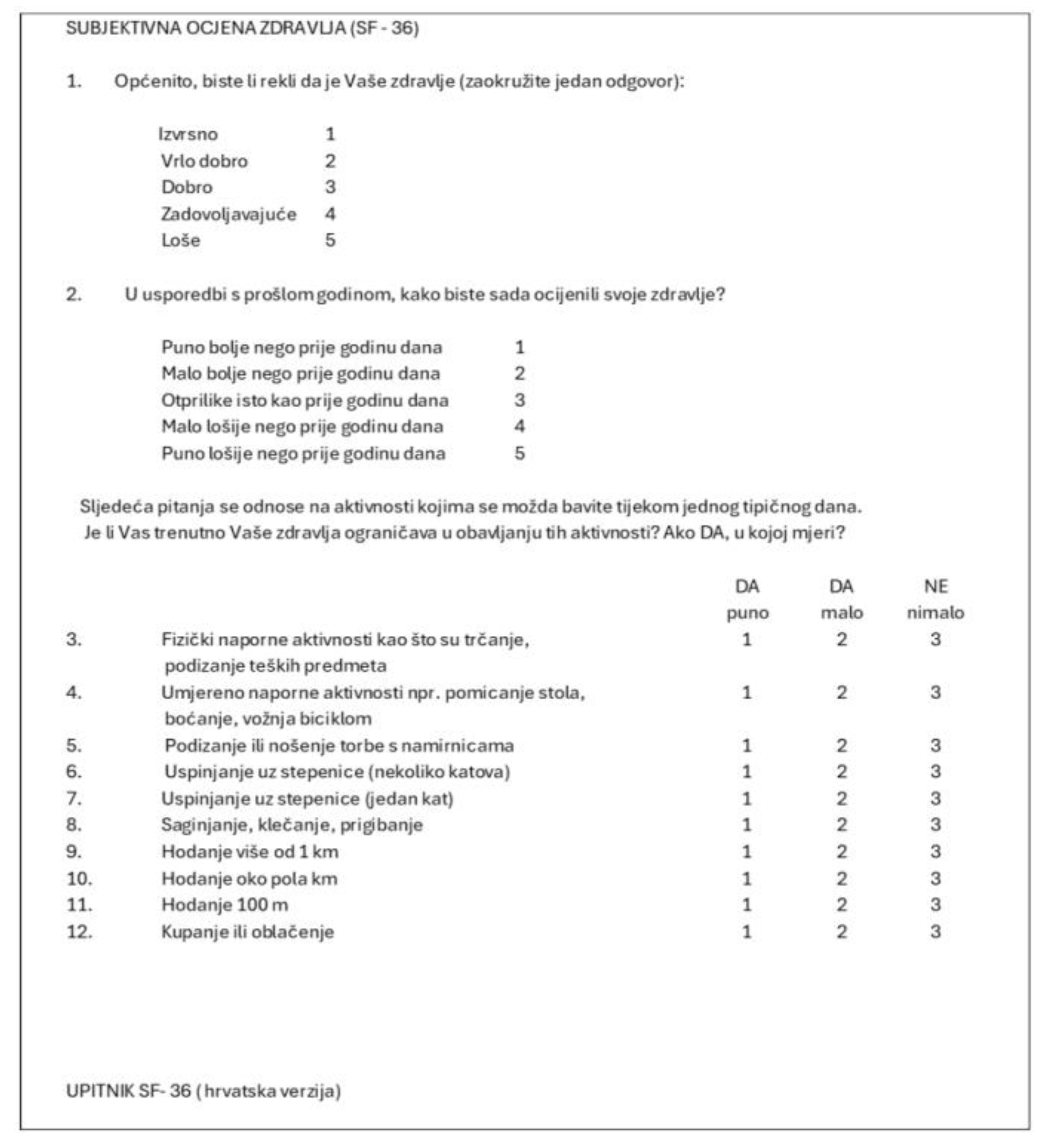

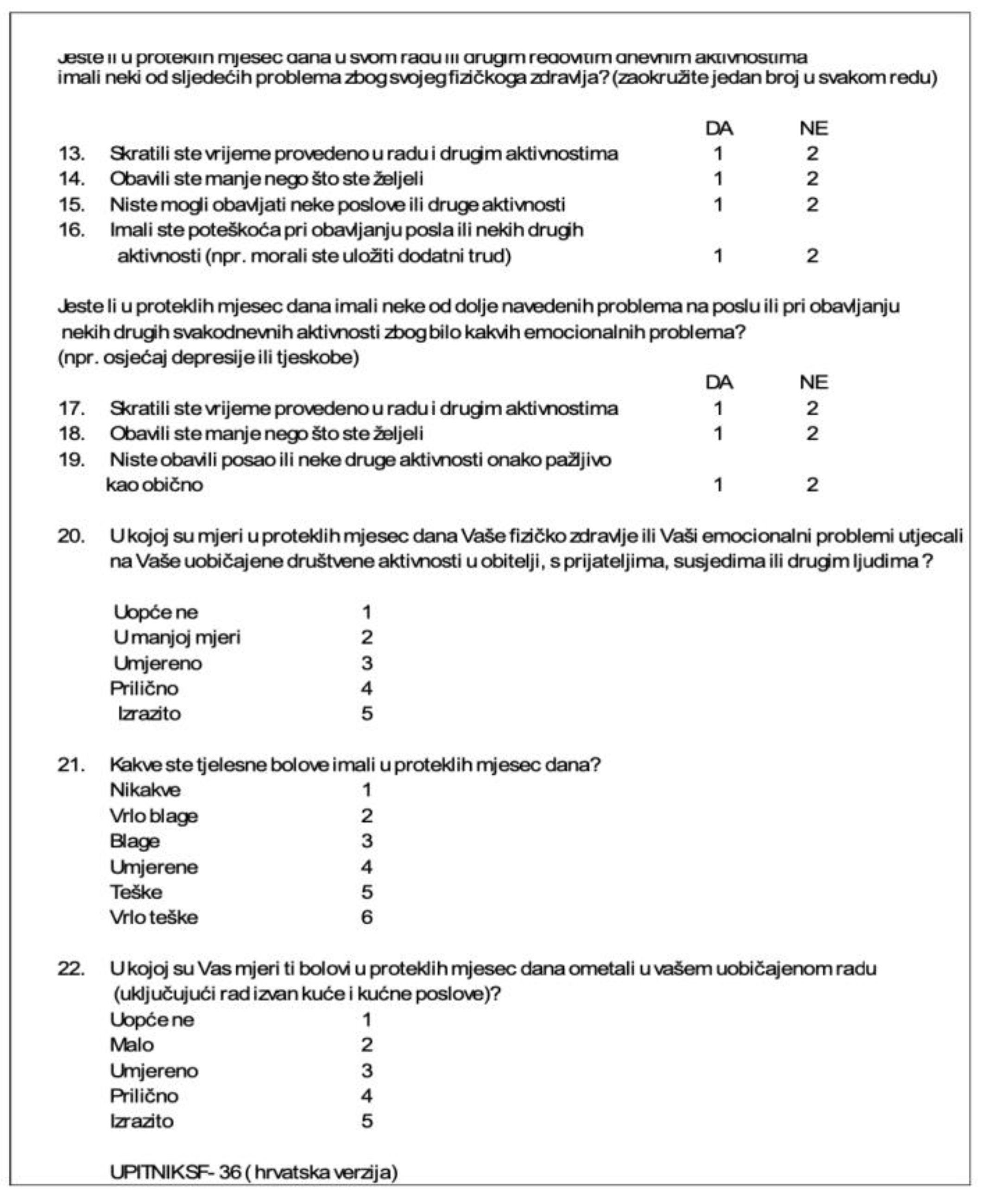

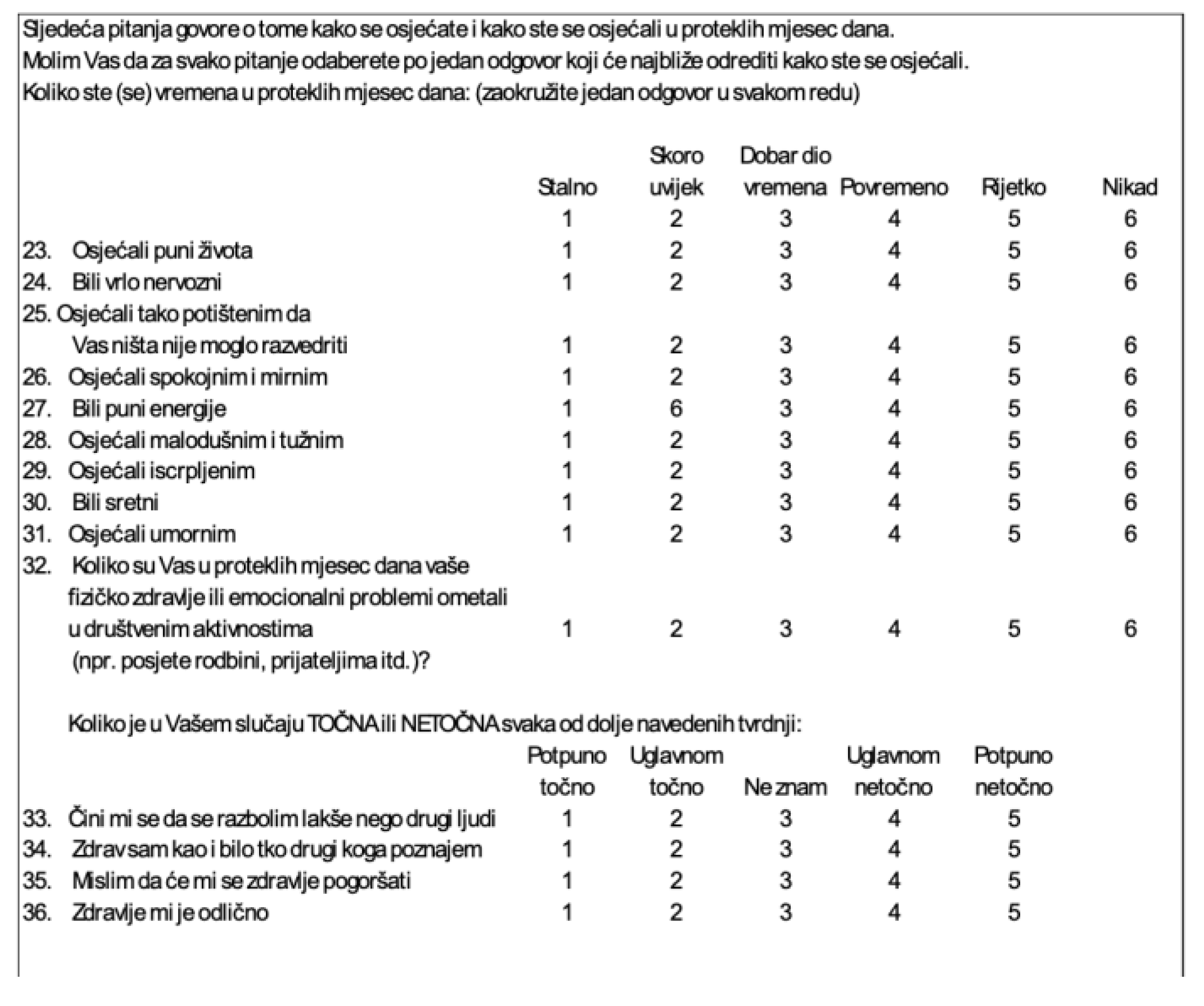

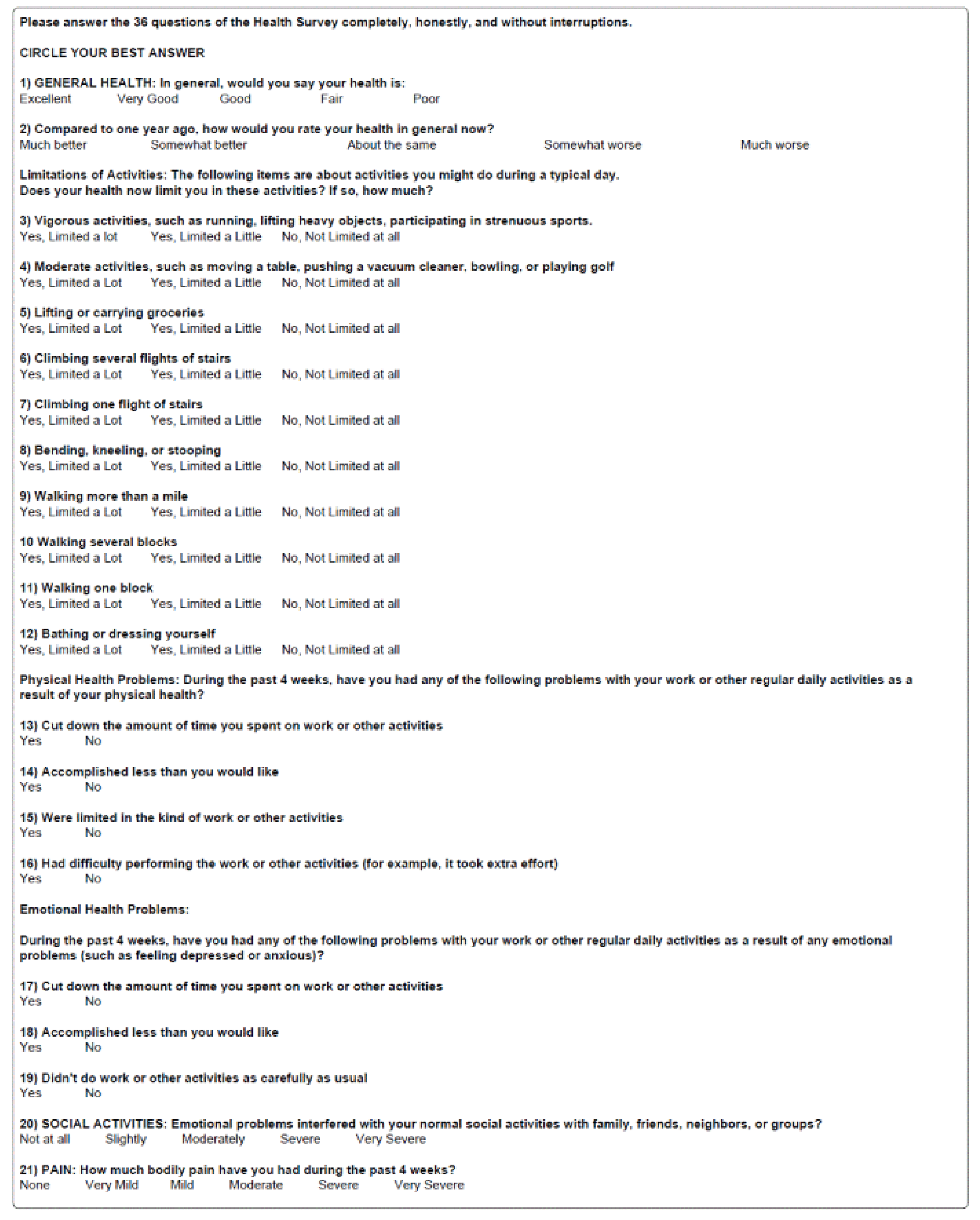

Our questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part was anonymous and was used to gain insight into the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients. It contained seven questions about gender, age, marital status (unmarried, married, divorced, or widowed), professional qualification (primary education, secondary education, or postsecondary education), employment (employed, unemployed, student, or retired), ENT diagnosis, and proposed future treatment (conservative or operative). Respondents were instructed to circle the answers that applied to them or enter their ages and diagnoses. The second part consisted of the SF-36 questionnaire, a health status questionnaire consisting of 36 items. The test measures health multidimensionally through the prism of the following aspects: physical functioning, constraints in functioning due to physical health, physical pain, social functioning, impairments in physical functioning due to emotional difficulties, vitality, psychological health, and a general self-assessment of one’s health status. The Croatian licensed version of the Andrija Štampar School of Public Health at the University of Zagreb was used [

8,

9] (see

Appendix A). The analysis of these aspects of one’s health and consequent QoL aims to analyze most of the contributors to a patient’s everyday functioning and consequent QoL with regard to the current diagnosis. It encompasses both physical constraints (physical pain, overall physical health status, and energy levels) and their role in everyday functioning, as well as the mental state and social functioning of patients, which have a reciprocal relationship [

4].

The goal of the data analysis was to investigate the relationship between the subjective quality of life of patients and their specific otorhinolaryngological diagnoses, coded by the current International Classification of Diseases (ICD). The numerical values of all eight subcategories of the questionnaire were compared—physical functioning, physical pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional state, and mental health—for patients within different groups.

Different areas of health were covered by a different number of questions, and their number was determined according to the psychometric criteria of reliability and validity. The question related to a change in health was shown separately. Each answer to the question was scored according to established norms. Therefore, the number of points obtained for each question was coded into standard values on a unique scale from 0 to 100 points, where a higher score indicates better health. A power analysis was conducted based on the average value of the SF-36 score according to the threshold value of a difference in questionnaire results of 5 points. Alpha was set to 0.05, with the power of the test being 80%. The power analysis set the minimum required sample size for the establishment of statistical significance to 78 respondents. The analysis of the normality of data distribution was verified by the Smirnov–Kolmogorov test, and according to the obtained results, non-parametric tests and the corresponding display were used, along with the appropriate representation of continuous values (arithmetic mean, standard deviation, and median). The data was analyzed with the Kruskal–Wallis test, using an implemented Dunn’s pairwise post hoc test option to correct for multiple analyses, and the Spearman rho correlation test. They were all two-way tests. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical processing and data analysis were performed using the MedCalc program (Version 11.2.1 © 1993–2010 MedCalc Software bvba Software, Broekstraat 52, 9030 Mariakerke, Belgium) and the SPSS program (Version 22.0. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

4. Discussion

When interpreting the results of this research, it is important to emphasize that objective medical outcomes are important, but they are not the only accurate indicators of quality of life, as they significantly depend on the subjective perception of each patient.

There have not been many studies focused on comparing the perceived quality of life among otorhinolaryngological patients. Most of the studies currently present in the literature focus on one category of diagnosis, such as oncology, otology, or audiology, and specific diagnoses within these categories [

5,

6,

7]. A study published in 2001 did compare the differences in QoL in otorhinolaryngology patients based on their diagnoses and demographic factors by using the SF-12 questionnaire [

10]. Since the study was published over 20 years ago, and a more recent version of the questionnaire has since been published, we intended to fill this gap in the literature with our study.

By analyzing the sociodemographic data of respondents from different diagnosis groups, it is evident that younger women undergo plastic-reconstructive procedures more often, while men of older ages are diagnosed with head and neck cancers more often (

Table S1 and

Figure 2). The age difference should be considered when interpreting the results of the research, as some age and consequent comorbidities could have a role in the overall QoL of patients, especially considering the fact that the patients in the reconstructive group were significantly younger than the participants in the other groups. Other variables were not significantly associated with the self-assessed quality of life, which shows that the perceived quality of life is an inherent property independent of the level of education and marital status.

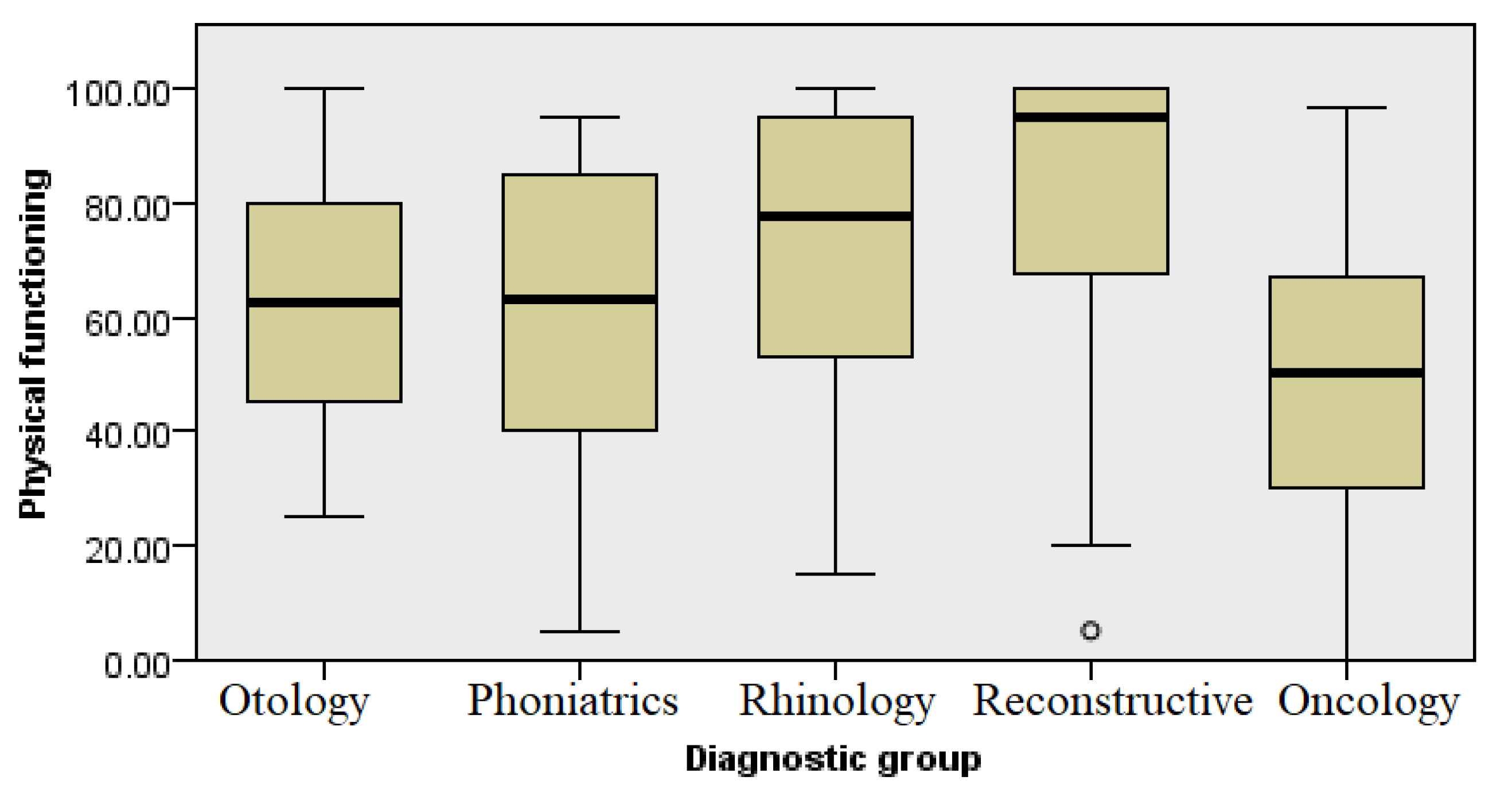

When assessing health status, the SF-36 questionnaire was used, which enabled a comprehensive assessment of the overall health status, with each diagnostic group showing a different average score in the eight questioned health domains. In the domain of physical functioning and health (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, respectively), patients differed in their rehabilitation requirements and capacities for daily activities, with some requiring more extensive physical rehabilitation or additional support.

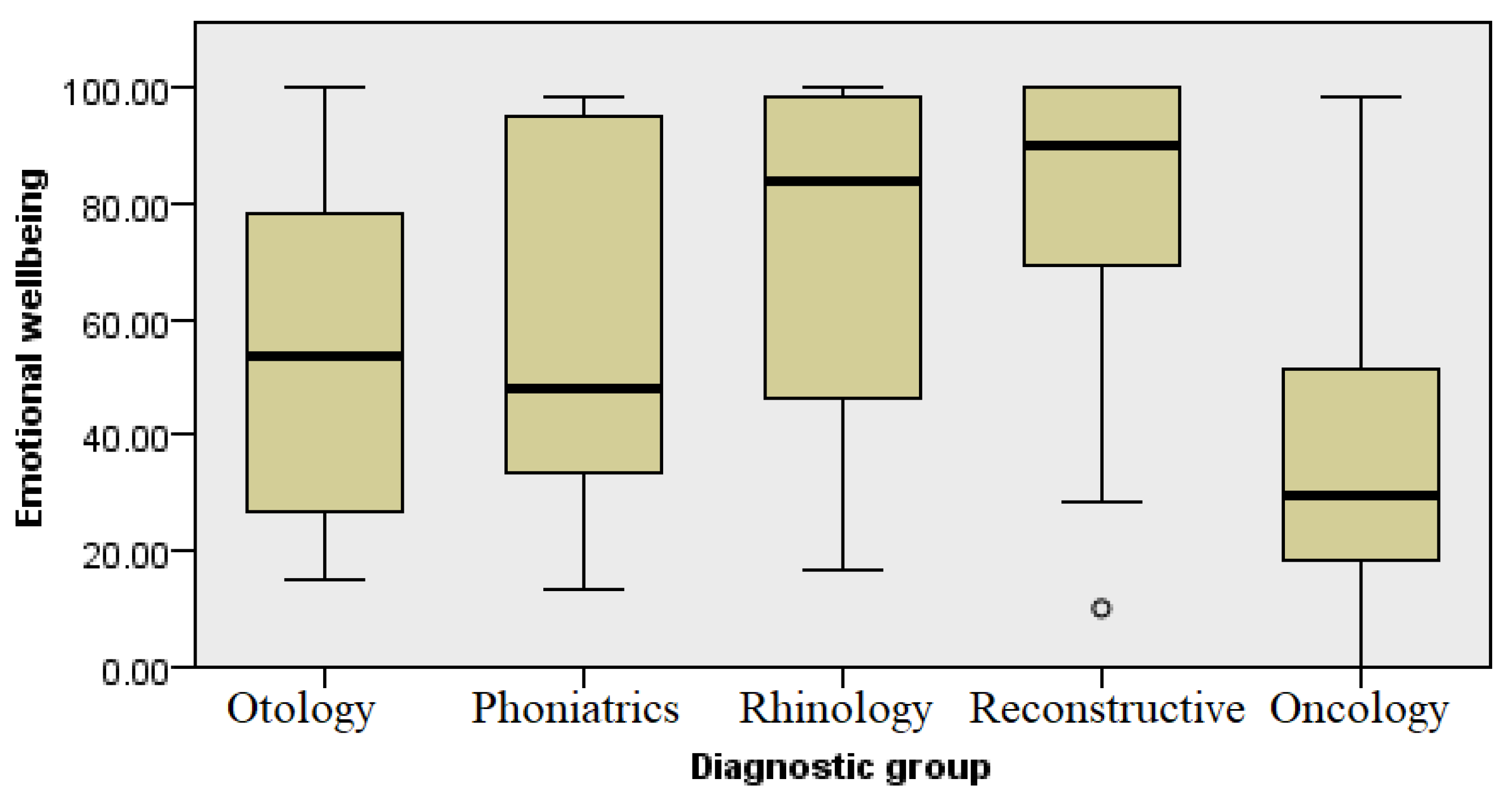

The emotional states and well-being of patients also differed by the different groups of diagnoses (

Figure 5 and

Figure 7, respectively). We could expect that this level would be significantly reduced in the oncology patients, primarily due to the social stigmatization associated with difficulties in communication, the need for frequent visits to the doctor as part of the long-term treatment, and the general challenges present in the treatment process of cancer patients. A decreased QoL has been noted in other studies, such as a study published by Berg et al. which demonstrated that patients with cancers at the base of the tongue have a lower QoL compared with the general population [

5]. However, patients with ear, hearing, and voice diseases also showed low levels of emotional well-being (

Figure 7). This can be associated with long-term treatment and restrictions that may affect daily activities, mostly related to personal hygiene and engaging in sports activities [

11]. Difficulties in communication and acceptance of surdo-technical aids are still stigmatized in elderly patients, leading to isolation and thus impairment of their quality of life. Similar results were shown in a study published by Bakir et al., where patients with chronic otitis media reported significantly lower levels of QoL compared with a control group [

6]. A decrease in QoL has also been noted in the literature among patients with functional voice disorders [

7]. These results indicate that the pathologies classified within these groups of diagnoses can be considered significantly limiting diseases in otorhinolaryngology.

Low scores related to the self-assessment of energy and fatigue (

Figure 6) in all four groups indicate a higher level of exhaustion due to underlying illness and the treatment process itself. The perception of pain in the group undergoing reconstructive procedures was at the lowest level and not significantly different when compared with other groups of respondents. This data can be used in healthcare planning and the application of continuous analgesia not only to oncology patients but also patients with other conditions and diagnoses in the field of otorhinolaryngology. Surgical resection followed by reconstruction in oncology patients may result in long-term pain, deformities, and possible limitations in shoulder and neck mobility. A loss of sense of taste often occurs after surgery which, in some patients, can be permanent, impairing the quality of life significantly more [

12,

13,

14]. Alongside the use of continuous analgesia, emphasis should be put on the rehabilitation and treatment of patients [

8]. The results of this research point to the need for individual medical care, whereby therapeutic approaches should be adapted not only to the patient’s physical condition but also the individual mental state, altering the guidelines and standard clinical practice to every individual whilst implementing shared decision making [

15]. The introduction of psychosocial support can significantly improve the quality of life, especially for patients with functionally limiting diagnoses.

This research was limited to patients in the one department of ENT and head and neck Surgery, which may have affected the objectivity of results. The methodological approach is based on the subjective assessment and interpretation of patients, which can also affect the results obtained. QoL in general is affected by multiple and diverse variables, some of which are the economic state, support from the community, and the quality of treatment of each patient, all of which are variables which are hard to control and take into account. The reconstructive group had a significant age difference compared with the other four groups, while different possible comorbidities in oncologic patients could impact self-perceived QoL. Sociodemographic variables were tested and did not differ among the groups, but one questionnaire cannot assess the details of every diagnostic category in the same way. However, although flawed, the authors endeavored to ensure that the analysis was rigorous enough to draw attention to the results, indicating that health is affected by more than just the diagnostic category; it is also affected by the multidimensional aspects of disease and treatment in the ENT field.