A Scoping Review of the Use and Determinants of Social Media Among College Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

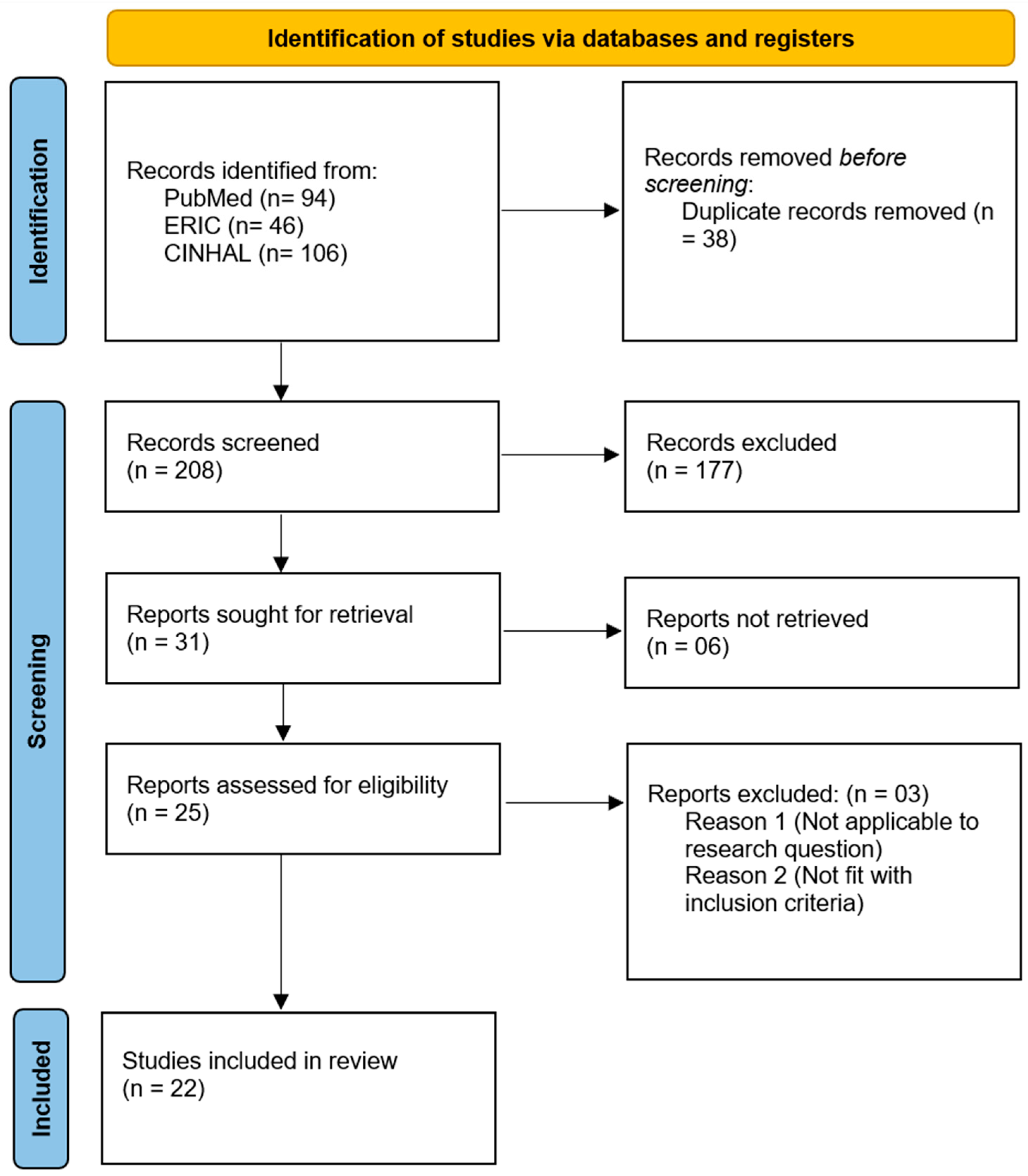

2.4. Selection Process

3. Results

| Study (Author, Year) | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Population | Social Media Platform(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jameel et al., 2025 [31] | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | 600 | University Students | Facebook and WhatsApp |

| Karaduman et al., 2025 [47] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 658 | University Students | General social media |

| Rahman et al., 2025 [41] | Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | 611 | University Students | Facebook and Messenger |

| Sun & Tang, 2025 [45] | China | Cross-sectional | 431 | University Students | WeChat, QQ, and Douyin |

| Thomas & George, 2025 [35] | India | Cross-sectional | 508 | University Students | Instagram and WhatsApp |

| Bawazeer et al., 2024 [42] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional | 389 | University Students | Snapchat and Instagram |

| Eymirli et al., 2024 [37] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 928 | University Students | Instagram and Twitter |

| Fruehwirth et al., 2024 [33] | USA | Cross-sectional | 2144 | University Students | Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok, and Twitter |

| Gao et al., 2024 [43] | USA | Longitudinal | 193 | College students with disabilities | Social networking platforms |

| Ghaderi, 2024 [48] | Iran | Cross-sectional | 1317 | University Students | General social media |

| Helmy et al., 2024 [39] | Egypt, Oman, Pakistan | Cross-national | 2616 | University Students | Smartphone and social media use |

| Lerma & Cooper, 2024 [20] | Spain | Cross-sectional | 2280 | University Students | General social media use |

| Li et al., 2024 [38] | China | Cross-sectional | 2582 | University Students | General social media |

| Oyinbo et al., 2024 [46] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 1416 | University Students | General social media |

| Pi et al., 2024 [44] | China | Cross-sectional | 710 | University Students | Sina Weibo and WeChat |

| Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2024 [49] | Spain | Cross-sectional | 690 | University students | General social media, gaming platforms |

| Shen et al., 2024 [29] | China | Longitudinal | 5568 | University freshmen | Mobile phones (general usage) |

| Sirtoli et al., 2024 [30] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 3161 | University Students | General social media |

| Üzer et al., 2024 [36] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 571 | University Students | General social media |

| Wang et al., 2024 [32] | China | Cross-sectional | 3236 | University Students | Smartphones |

| Yan et al., 2024 [34] | China | Cross-sectional | 2507 | University students | Smartphones |

| Yuan et al., 2024 [40] | China | Cross-sectional | 1294 | University students | Smartphones (general use) |

| Study (Author, Year) | Aim of the Study | Key Determinants | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jameel et al., 2025 [31] | To analyze the association between social media addiction (SMA) and mental health issues (e.g., depressive symptoms) among Saudi university students, and explore insomnia’s mediating role. | Time spent, depression, and anxiety | Social media addiction directly predicted mental health issues (β = 0.315, p < 0.001) and insomnia (β = 0.537, p < 0.001). Insomnia mediated the SMA–mental health link (indirect β = 0.187, p < 0.001), explaining 18.7% of the effect. |

| Karaduman et al., 2025 [47] | To assess social-media-addiction levels among nursing and midwifery undergraduates, identify influencing factors, and test whether addiction predicts mental fatigue | Loneliness and fear of missing out (FoMO) | Social-media addiction scores were generally low but still predicted higher mental fatigue (p < 0.01). In regression, the mood-regulation and conflict components of addiction each showed significant contributions to fatigue (p = 0.011; p < 0.001), together explaining a meaningful share of variance. |

| Rahman et al., 2025 [41] | To examine the associations between social media addiction (SMA), social media fatigue (SMF), fear of missing out (FoMO), and sleep quality (SQ) among university students in Bangladesh. | SMA, SMF, and FoMO | Students with lower SMA, SMF, and FoMO scores were significantly more likely to have good sleep quality (AORs: 2.04, 6.85, 2.22, respectively; all p < 0.001). Those spending over 8 h/day on social media had significantly poorer sleep (AOR = 0.20; p < 0.001) and worse self-reported health. |

| Sun & Tang, 2025 [45] | To revise and validate the Problematic Smartphone Use Scale for Chinese college students (PSUS-C) and test its psychometric properties and measurement invariance across demographic groups. | PSUS-C demonstrated strong criterion validity: positively correlated with depression (r = 0.451, p < 0.001), loneliness (r = 0.455–0.504, p < 0.001), social media addiction (r = 0.614, p < 0.001), and phone usage duration (r = 0.148, p < 0.001); negatively correlated with life satisfaction (r = −0.218, p < 0.001) and self-esteem (r = −0.416, p < 0.001). | |

| Thomas & George, 2025 [35] | To examine relationships between Fear of Missing Out (FoMO), emotional distress, and problematic social media use (PSMU) among university students in India. | FOMO, anxiety, and emotional distress | FoMO significantly correlated with depression (r = 0.320, p < 0.05), anxiety (r = 0.326, p < 0.05), and stress (r = 0.317, p < 0.05). Females reported higher anxiety than males (p = 0.007). |

| Bawazeer et al., 2024 [42] | To examine the relationship between social media use and dietary habits among college students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. | Nomophobia (the fear or anxiety associated with being without a mobile phone or unable to use it) and daily usage | Students spending ≥ 4 h/day on social media had significantly poorer dietary habits (p = 0.029). Significant differences in dietary scores were noted for students without children (p = 0.029), without medical issues (p = 0.039), and those following specific dietary plans (p < 0.001), suggesting negative impacts from extensive social media usage. |

| Eymirli et al., 2024 [37] | To evaluate healthy lifestyle behaviors, physical activity levels, and social media use among dental students. | Self-esteem and loneliness | Most students (64.3%) had low physical activity; 23.1% were inactive. Higher lifestyle scores correlated positively with increased physical activity (p < 0.001). No gender differences in lifestyle behaviors or physical activity. Males showed significantly higher obesity and tobacco use (p < 0.05). |

| Fruehwirth et al., 2024 [33] | To assess the causal effects of social media use on mental health (depression and anxiety) among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Loneliness, depressive symptoms, and social media use frequency | Social media use had no significant effect on mental health 4 months into the pandemic, but significantly worsened depression (β = 0.54, p < 0.05) and anxiety (β = 0.47, p < 0.10) symptoms at 18 months. Effects were strongest among socially isolated students (p < 0.05). |

| Gao et al., 2024 [43] | Track one-year changes in social media addiction and its impact on career networking among college students with disabilities. | Addiction levels, networking use, and disability subtypes | Social media addiction increased significantly over one year (p = 0.02). Career networking via social media increased (p < 0.001). Male students showed a sharper rise in addiction than females (p < 0.05). Students with psychological disabilities increased career networking faster than those with physical disabilities (p < 0.05). |

| Ghaderi, 2024 [48] | To determine whether screen time, social networking use, and physical activity predict depression levels among Qazvin University students. | Social support and self-esteem | Among 146 undergraduates, greater daily screen time significantly correlated with higher depression scores (r = 0.35, p < 0.01) and independently predicted symptoms (β = 0.33, p = 0.001), explaining 13% of variance; social network use and physical activity showed no significant associations. |

| Helmy et al., 2024 [39] | To determine rates of alexithymia and its relationship with smartphone addiction and psychological distress among university students across Egypt, Oman, and Pakistan. | Alexithymia, smartphone addiction, and psychological distress | University students found 43% struggled to name emotions, 65% were addicted to smartphones, and 70% had high stress. Those with emotion-naming struggles were very likely to have phone addiction (p < 0.001) and distress (p < 0.001). Women had more emotion-naming issues than men (p < 0.001), and Oman had the highest phone addiction rate (p < 0.01). |

| Lerma & Cooper, 2024 [20] | To explore sociocultural, behavioral, and physical factors influencing excessive social media use, addiction, self-control failure, and motivation to reduce usage among Hispanic college students. | Self-control, self-esteem, and academic burnout | Social media addiction positively correlated with posting frequency in Spanish (p < 0.001), fear of missing out (p = 0.02), social media craving (p < 0.001), and home restrictions (p = 0.04). Motivation to reduce usage was higher among U.S. residents than Mexico (p = 0.05). |

| Li et al., 2024 [38] | To determine whether social withdrawal predicts problematic social media use in Chinese college students and to test alexithymia and negative body image as independent and chained mediators. | Social withdrawal, alexithymia, and negative body image | Among 2582 Chinese undergraduates, social withdrawal predicted greater problematic social media use (p < 0.001). Alexithymia and negative body image each partially mediated the link (p < 0.001) and combined in a significant chain (p < 0.001), explaining 42% of the indirect effect; the overall model fit was excellent |

| Oyinbo et al., 2024 [46] | To investigate the association between daily social media use and perceived stress among college students in the U.S. | Smartphone addiction and academic procrastination | Female students spending > 2 h/day on social media reported significantly higher stress levels compared to those spending ≤ 20 min/day (β = 4.74, 95% CI: 1.25–8.24, p < 0.05), highlighting prolonged social media use as an independent predictor of perceived stress. |

| Pi et al., 2024 [44] | To identify latent profiles of problematic mobile social media usage (PMSMU) among Chinese college students and assess factors such as FOMO, online feedback, and boredom. | Academic stress and usage duration | Three latent PMSMU profiles emerged: no-problem (26.44%), mild (56.66%), and severe (16.91%). Higher FOMO (OR = 2.91), boredom (OR = 8.72), and online positive feedback (OR = 1.42) significantly predicted severe PMSMU (p < 0.01 to p < 0.001). Females showed a higher risk (p < 0.001). |

| Sánchez-Fernández et al., 2024 [49] | To examine psychological factors associated with generalized problematic internet use (GPIU), problematic social media use (PSMU), and problematic online gaming (POG) among university students | Psychological distress, cognitive distortions, impulsiveness, and coping motives | High cognitive distortions (p < 0.001) and cognitive reappraisal (p < 0.01) were associated with GPIU, PSMU, and POG. Psychological distress, low conscientiousness, and motor impulsivity significantly predicted GPIU and PSMU (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001), but not POG. Neuroticism showed no significant association. |

| Shen et al., 2024 [29] | Examine the directionality between problematic mobile phone use (PMPU) symptoms and negative emotions in 5568 Chinese freshmen over one academic year using a cross-lagged panel network design | Academic burnout, social anxiety, escapism, and internet use motives | Baseline academic burnout predicted increased social-media and gaming use, plus all PMPU symptoms and negative emotions at follow-up (β = 0.01–0.04, p < 0.001). Bidirectional cycles linked escapism with social anxiety and inability to control craving (β ≈ 0.02–0.04, p < 0.01), with productivity loss emerging as the most central node. |

| Sirtoli et al., 2024 [30] | Estimate the association between time spent on social media (TSSM) and depressive symptoms in university students, and test whether tobacco, alcohol and illicit-drug use mediate that link | Tobacco and alcohol, illicit drug use | Among 3161 Brazilian students, longer daily social-media time predicted greater depressive symptoms (p < 0.001). Tobacco use (p = 0.02), alcohol risk (p < 0.001), and illicit-drug risk (p < 0.001) each partially mediated this association, together accounting for over two-thirds of the indirect effect after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, and physical activity. |

| Üzer et al., 2024 [36] | Examine how chronotype, psychological pain, problematic social-media use (PSMU), internet addiction, anxiety and depression interrelate with suicidality in Turkish university students, and test whether PSMU and psychological pain mediate the chronotype-suicidality link. | Evening chronotype and psychological pain | Among 571 students, higher psychological pain and PSMU independently predicted greater suicidality (p < 0.001). Evening chronotype was associated with higher suicidality (p = 0.009) and its effect was fully mediated by PSMU and psychological pain (p < 0.001); internet addiction, anxiety and depression showed no significant mediation. |

| Wang et al., 2024 [32] | To examine the longitudinal relationship between self-esteem and problematic social media use (PSMU) among Chinese college students. | Sleep quality, depressive, and anxiety symptoms | Self-esteem negatively predicted problematic social media use longitudinally (β = −0.151 to −0.132, p < 0.01 to p < 0.05). Initial self-esteem negatively predicted initial PSMU (β = −0.711, p < 0.01), and declining self-esteem predicted increasing PSMU (β = −0.708, p < 0.05). |

| Yan et al., 2024 [34] | To test whether the intensity of mobile social media use predicts depressive mood in college students and to determine if upward social comparison and cognitive overload act as mediators. | Perceived stress and academic stress | Among 568 Chinese students, greater social media use intensity was related to higher depressive mood (p < 0.001). Upward social comparison and cognitive overload each fully mediated this association (p < 0.01) and sequentially combined in a chain mediation (p < 0.001), nullifying the direct effect. |

| Yuan et al., 2024 [40] | To investigate longitudinal associations between negative life events and problematic social media use (PSMU) among Chinese college students, focusing on the mediating role of fear of missing out (FoMO) and moderation by positive parenting. | Social support and emotional intelligence | Negative life events increased PSMU directly and via higher FoMO (p < 0.001). Positive parenting significantly moderated the relationship between fear of missing social opportunities and PSMU (p = 0.019), indicating a protective effect against developing problematic social media behaviors. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Uses of Social Media for Changing Health Behaviors

4.2. Strengths of the Studies

4.3. Limitations of the Studies

4.4. Strengths of the Review

4.5. Limitations of the Review

4.6. Implications for Practice

4.7. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TLA | Three-letter acronyms |

| FoMO | Fear of missing out |

| PSMU | Problematic social media use |

References

- Gottfried, M.A. Michelle Faverio and Jeffrey Teens, Social Media and Technology 2023; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, C.T.; Lebret, R.; Aberer, K. Multimodal Classification for Analysing Social Media. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.02099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the World, Unite! The Challenges and Opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, R.; Ruhi, U. Social Media in Higher Education: A Literature Review of Facebook. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2018, 23, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolhar, M.; Kazi, R.N.A.; Alameen, A. Effect of Social Media Use on Learning, Social Interactions, and Sleep Duration among University Students. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2216–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryville, U. The Evolution of Social Media: How Did It Begin, and Where Could It Go Next; Maryville University Online: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reid Chassiakos, Y.L.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Council on Communications and Media; Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Hutchinson, J.; Levine, A.; et al. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pempek, T.A.; Yermolayeva, Y.A.; Calvert, S.L. College Students’ Social Networking Experiences on Facebook. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 30, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Jaoude, E.; Naylor, K.T.; Pignatiello, A. Smartphones, Social Media Use and Youth Mental Health. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E136–E141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, T.; Turan, A.H. The Relationships Among Social Media Intensity, Smartphone Addiction, and Subjective Wellbeing of Turkish College Students. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 1999–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, C.T.; Moran-Miller, K.; Levy, H.F.; Gray, T. Social Media Engagement, Perceptions of Social Media Costs and Benefits, and Well-Being in College Student-Athletes. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 2938–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, J.; Martínez-López, J.Á.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Sarasola Sánchez-Serrano, J.L. Social Networks Consumption and Addiction in College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Educational Approach to Responsible Use. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruska, J.; Maresova, P. Use of Social Media Platforms among Adults in the United States—Behavior on Social Media. Societies 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Aman, J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Bano, S. The Impact of Social Media on Learning Behavior for Sustainable Education: Evidence of Students from Selected Universities in Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Mou, Q.; Zheng, T.; Gao, F.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, M. A Serial Mediation Model of Social Media Addiction and College Students’ Academic Engagement: The Role of Sleep Quality and Fatigue. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.L.; Raphael, J.L.; McGuire, A.L. HEADS4: Social Media Screening in Adolescent Primary Care. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20173655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albikawi, Z.F. Anxiety, Depression, Self-Esteem, Internet Addiction and Predictors of Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization among Female Nursing University Students: A Cross Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhawyan, A.F.; Alfaraj, A.A.; Elyahia, S.A.; Alshehri, S.Z.; Alghamdi, A.A. Determinants of Subjective Poor Sleep Quality in Social Media Users Among Freshman College Students. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2020, 12, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerma, M.; Marquez, C.; Sandoval, K.; Cooper, T.V. Psychosocial Correlates of Excessive Social Media Use in a Hispanic College Sample. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekalu, M.A.; Sato, T.; Viswanath, K. Conceptualizing and Measuring Social Media Use in Health and Well-Being Studies: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuck, A.B.; Thompson, R.J. The Social Media Use Scale: Development and Validation. Assessment 2024, 31, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoga, S.V.; Erlyana, E.; Rebello, V. Associations of Social Media Use With Physical Activity and Sleep Adequacy Among Adolescents: Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, M. Mobile Messaging and Social Media 2015; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A Systematic Review: The Influence of Social Media on Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhead, S.A.; Hazlett, D.E.; Harrison, L.; Carroll, J.K.; Irwin, A.; Hoving, C. A New Dimension of Health Care: Systematic Review of the Uses, Benefits, and Limitations of Social Media for Health Communication. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purba, A.K.; Thomson, R.M.; Henery, P.M.; Pearce, A.; Henderson, M.; Katikireddi, S.V. Social Media Use and Health Risk Behaviours in Young People: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2023, 383, e073552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Huang, G.; Wang, M.; Jian, W.; Pan, H.; Dai, Z.; Wu, A.M.S.; Chen, L. The Longitudinal Relationships between Problematic Mobile Phone Use Symptoms and Negative Emotions: A Cross-Lagged Panel Network Analysis. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 135, 152530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirtoli, R.; Fernández-Rodríguez, R.; Balboa-Castillo, T.; Rodrigues, R.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Eumann Mesas, A.; Morales, G.; Molino Guidoni, C. Time Spent on Social Media and Depressive Symptoms in University Students: The Mediating Role of Psychoactive Substances. Am. J. Addict. 2024, 33, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameel, A.; Guo, W.; Hussain, A.; Kanwel, S.; Sahito, N. Exploring the Mediating Role of Insomnia on the Nexus between Social Media Addiction and Mental Health among University Students. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. Relationship Between Self-Esteem and Problematic Social Media Use Amongst Chinese College Students: A Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruehwirth, J.C.; Weng, A.X.; Perreira, K.M. The Effect of Social Media Use on Mental Health of College Students during the Pandemic. Health Econ. 2024, 33, 2229–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Long, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, X.; Xie, B.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Mobile Social Media Use on Depressive Mood Among College Students: A Chain Mediating Effect of Upward Social Comparison and Cognitive Overload. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; George, M.A. Fear of Missing out (FOMO), Emotional Distress, and Problematic Social Media Use among University Student. Indian. J. Psychiatr. Soc. Work. 2025, 16, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzer, A.; Uran, C.; Yılmaz, E.; Şahin, Ş.N.; Ersin, M.K.; Yılmaz, R.H.; Çıkla, A. The Relationship between Chronotype, Psychological Pain, Problematic Social Media Use, and Suicidality among University Students in Turkey. Chronobiol. Int. 2024, 41, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar Eymirli, P.; Mustuloğlu, Ş.; Köksal, E.; Turgut, M.D.; Uzamiş Tekçiçek, M. Dental Students’ Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors, Physical Activity Levels and Social Media Use: Cross Sectional Study. Discov. Public Health 2024, 21, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Sun, C. The Relationship between Social Withdrawal and Problematic Social Media Use in Chinese College Students: A Chain Mediation of Alexithymia and Negative Body Image. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, M.; Ebrahim, A.H.; Faqeeh, A.; Engel, E.; Ashraf, F.; Isaac, B.A. Relationship Between Alexithymia, Smartphone Addiction, and Psychological Distress Among University Students: A Multi-Country Study. Oman Med. J. 2024, 39, e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Dou, K.; Li, Y. The Longitudinal Association Between Negative Life Events and Problematic Social Media Use Among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of FoMO and the Moderating Role of Positive Parenting. Stress. Health 2024, 40, e3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Kim, Y.S.; Noh, M.; Lee, C.K. A Study on the Determinants of Social Media Based Learning in Higher Education. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2021, 69, 1325–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazeer, N.M.; Almalki, S.; Alanazi, R.; Alamri, R.; Alanzi, R.; Alhanaya, R.; Alhashem, A.; Aldahash, R. Examining the Association between Social Media Use and Dietary Habits among College Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J. Community Health 2025, 50, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Eissenstat, S.J.; DeMasi, M. A One-Year Follow-up Study of Changes in Social Media Addiction and Career Networking among College Students with Disabilities. J. Am. Coll. Health 2024, 72, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zou, L.; Mo, X.; Guo, L. An Analysis of the Latent Class and Influencing Factors of Problematic Mobile Social Media Usage Among Chinese College Students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Tang, K. Psychometric Evaluation and Measurement Invariance of the Problematic Smartphone Use Scale among College Students: A National Survey of 130 145 Participants. Addiction 2025, 120, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyinbo, A.G.; Heavner, K.; Mangano, K.M.; Morse, B.; El Ghaziri, M.; Thind, H. Prolonged Social Media Use and Its Association with Perceived Stress in Female College Students. Am. J. Health Educ. 2024, 55, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaduman, C. The Relationship Between Social Media Addiction and Mental Fatigue Levels in Faculty of Health Sciences Students: A Descriptive and Relational Study. J. Educ. Res. Nurs. 2025, 22, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, D. The Relationship Between Screen Time, Social Network Usage, and Physical Activity with Depression in Students at Qazvin University. Asian J. Sports Med. 2024, 15, e147095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Fernández, M.; Borda-Mas, M.; Horvath, Z.; Demetrovics, Z. Similarities and Differences in the Psychological Factors Associated with Generalised Problematic Internet Use, Problematic Social Media Use, and Problematic Online Gaming. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 134, 152512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhao, J.; Tong, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. Too Much Social Media? Unveiling the Effects of Determinants in Social Media Fatigue. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1277846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, N.; Sharma, S. Smartphone Use and Its Addiction among Jammu Adolescents. Indian. J. Community Health 2024, 36, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Nie, Y.; Liu, Q. Does the Effect of Stress on Smartphone Addiction Vary Depending on the Gender and Type of Addiction? Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhafi, M.; Matrood, R.; Alamoudi, M.; Alshaalan, Y.; Alassafi, M.; Omair, A.; Harthi, A.; Layqah, L.; Althobaiti, M.; Shamou, J.; et al. The Association of Smartphone Usage with Sleep Disturbances among Medical Students. Avicenna J. Med. 2024, 14, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowthian, E.; Fee, G.; Wakeham, C.; Clegg, Z.; Crick, T.; Anthony, R. Identifying Protective and Risk Behavior Patterns of Online Communication in Young People. J. Adolesc. 2024, 96, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegeman, P.; Vader, D.; Kamke, K.; El-Toukhy, S. Patterns of Digital Health Access and Use among US Adults: A Latent Class Analysis. BMC Digit. Health 2024, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, E.P.; Kunte, S.A.; Wu, K.A.; Kaplan, S.; Hwang, E.S.; Plichta, J.K.; Lad, S.P. Digital Health Platforms for Breast Cancer Care: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doelvia, A.; Hien, V.T.T.; Rathee, S. Assessment: The Effectiveness of Video Media Through the Tiktok Application on Teenagers’ Knowledge About Clean and Healthy Living Behavior at Junior High School Level. J. Eval. Educ. 2023, 4, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, E.; De Leeuw, E. Theories of the Policy Process in Health Promotion Research: A Review. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. The Impact of Smartphone Addiction on Mental Health and Its Relationship with Life Satisfaction in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1542040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C. Analysis Of the Impact of New Media on College Students’ Mental Health. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 28, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatmanti, N.M.; Septianingrum, Y.; Fitriasari, A.; Martining Wardani, E.; Setiyowati, E. Smartphone Addiction Screening Application Development Based on Android: A Preeliminary Study. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 482, 05001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Awan, A.; Kapukotuwa, S.; Kanekar, A. A Fourth-Generation Multi-Theory Model (MTM) of Health Behavior Change: Genesis, Evidence, and Potential Applications. In Handbook of Concepts in Health, Health Behavior and Environmental Health; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–39. ISBN 978-981-97-0821-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kapukotuwa, S.; Nerida, T.; Batra, K.; Sharma, M. Utilization of the Multi-Theory Model (MTM) of Health Behavior Change to Explain Health Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Health Promot. Perspect. 2024, 14, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, E.; Boland, A.; Bell, I.; Nicholas, J.; La Sala, L.; Robinson, J. The Mental Health and Social Media Use of Young Australians during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, G.; Lo Scalzo, L.; Giuffrè, M.; Ferrara, P.; Corsello, G. Smartphone Use and Addiction during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic: Cohort Study on 184 Italian Children and Adolescents. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.S.; Way, B.M. Social Media Use and Systemic Inflammation: The Moderating Role of Self-Esteem. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2021, 16, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Term | Associated Terms | Exclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Social media | “Social media”, “social networking sites”, “online social networks” | Studies not focused on social media platforms |

| College Students | “College students”, “university students” | Non-college youth, adults outside the college/university context |

| Determinants/Factors/Influences | “determinants”, “factors”, “influences” | Studies not addressing specific influences on social media use |

| Use/Usage/Engagement/Behavior | “use”, “usage”, “engagement”, “behavior” | Studies that do not focus on social media usage or engagement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fatima, A.; Akhter, M.S.; Kanekar, A.; Roy, S.; Mitra, R.; Imade, B.; Sharma, M. A Scoping Review of the Use and Determinants of Social Media Among College Students. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2234. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172234

Fatima A, Akhter MS, Kanekar A, Roy S, Mitra R, Imade B, Sharma M. A Scoping Review of the Use and Determinants of Social Media Among College Students. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2234. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172234

Chicago/Turabian StyleFatima, Anam, Md. Sohail Akhter, Amar Kanekar, Sharmistha Roy, Rupam Mitra, Blessing Imade, and Manoj Sharma. 2025. "A Scoping Review of the Use and Determinants of Social Media Among College Students" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2234. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172234

APA StyleFatima, A., Akhter, M. S., Kanekar, A., Roy, S., Mitra, R., Imade, B., & Sharma, M. (2025). A Scoping Review of the Use and Determinants of Social Media Among College Students. Healthcare, 13(17), 2234. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172234