Occupational Therapy Interventions in Mental Health During Lockdown: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Studies published in English or Spanish.

- Studies with full text available.

- Studies conducted by occupational therapists, either exclusively or together with other professionals.

- Studies in which an intervention during COVID-19 and/or its lockdown was carried out.

- Studies where the intervention targeted mental health, including anxiety, depression, well-being, social stress, quality of life, or motivation.

- Studies with experimental or quasi-experimental designs.

- Studies published in other languages.

- Studies whose intervention was not focused on mental health.

- Studies with a team which did not include an occupational therapist.

- Studies with an intervention period outside the COVID-19 timeframe.

- Studies with the following designs: abstracts, editorials, letters to the editor, opinions, reviews, brief reports, conference papers, books, book chapters, scale validation studies, qualitative studies, mixed methods studies, case reports, animal studies, pilot studies, case studies, observational studies, protocols, and exploratory studies.

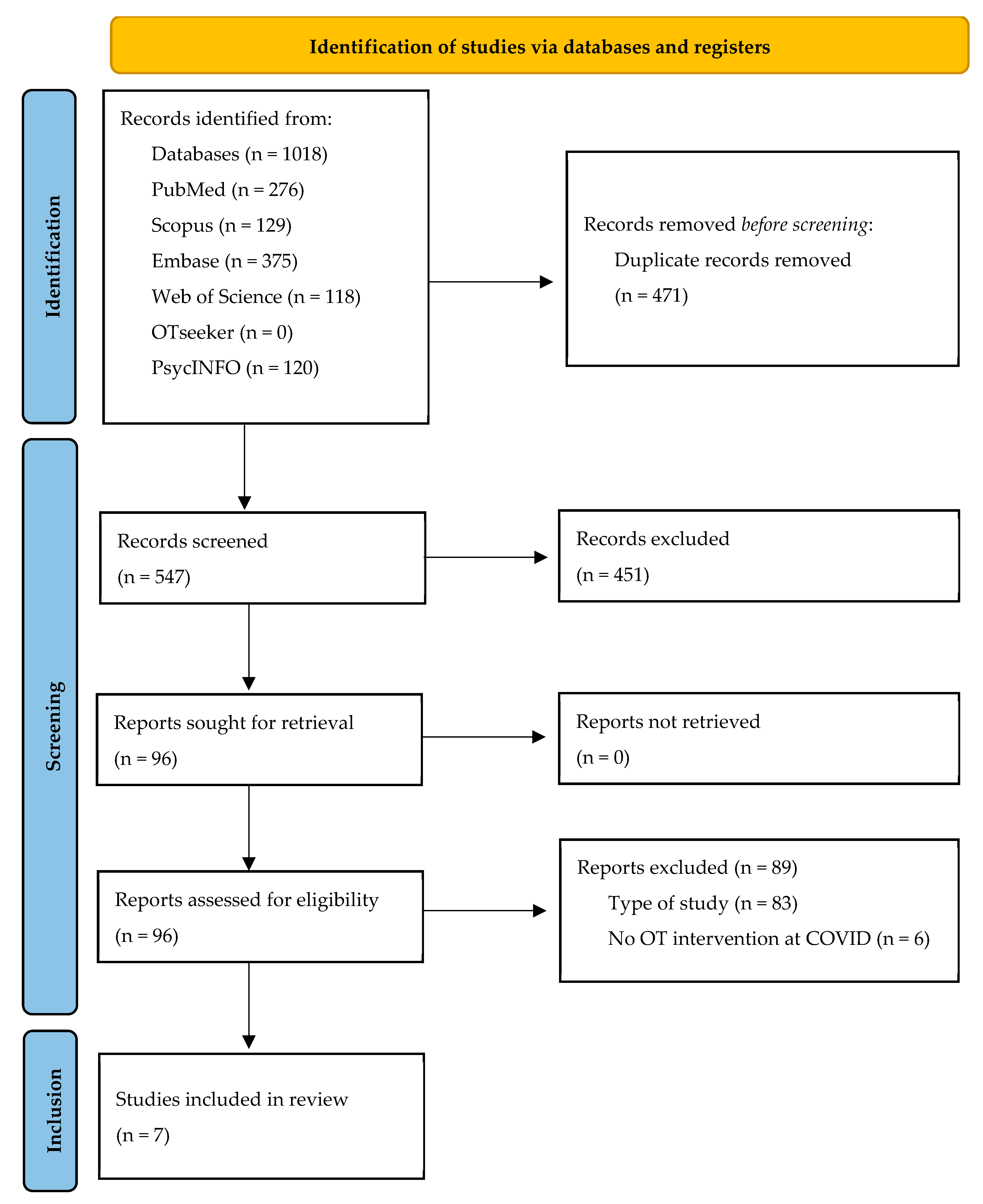

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

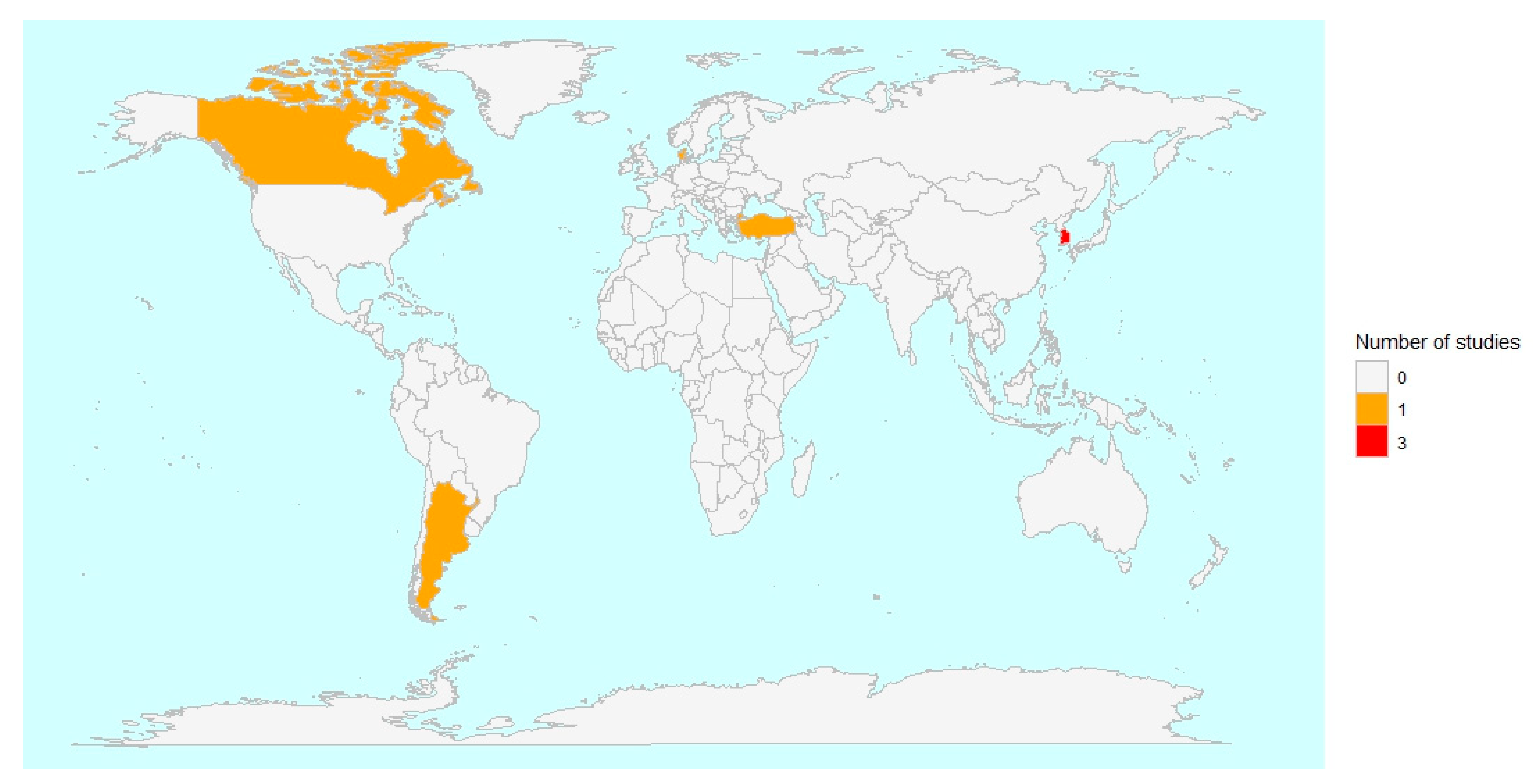

3.1. Main Characteristics of the Included Studies

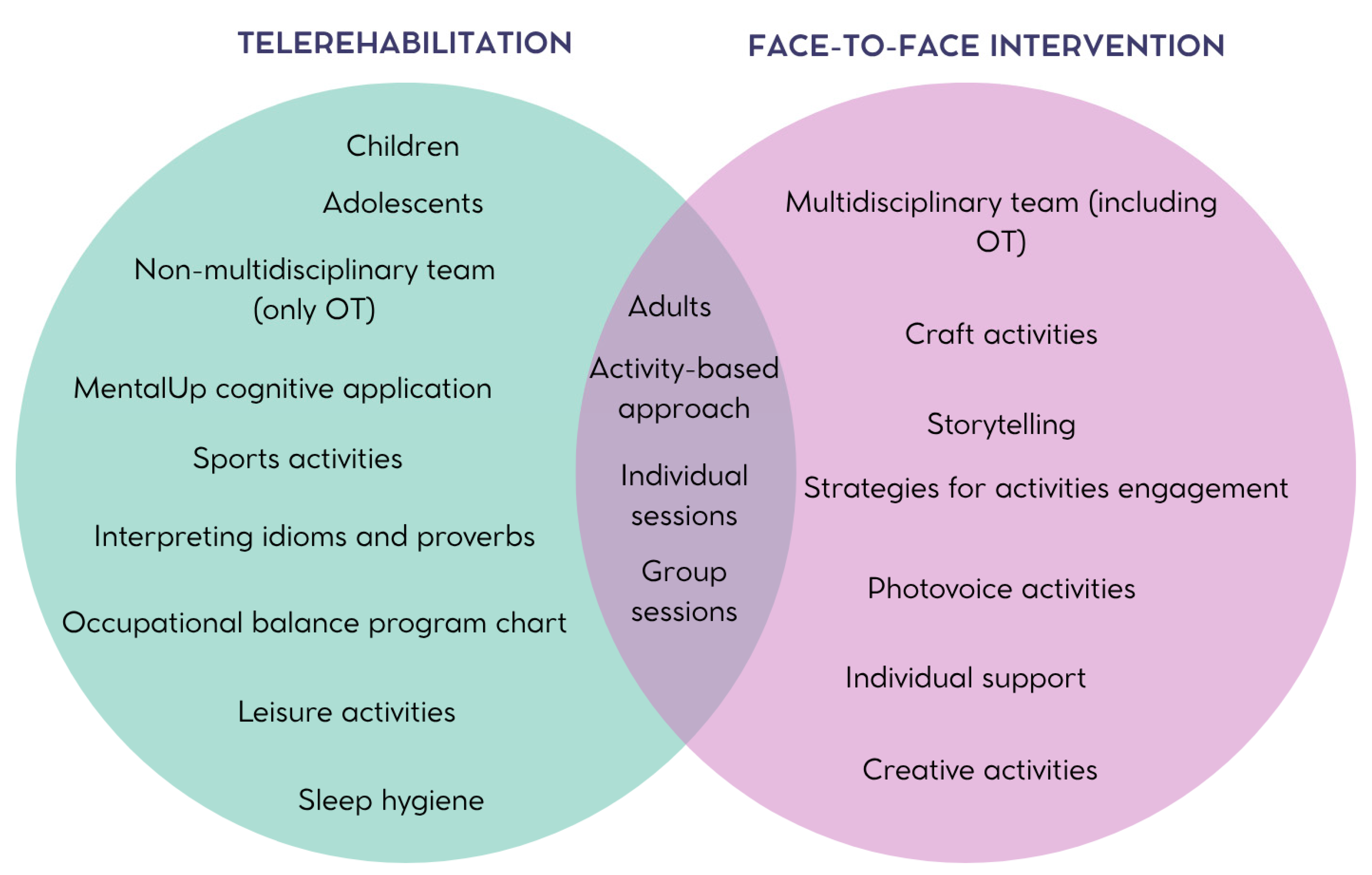

3.2. Occupational Therapy Interventions

3.3. Study Variables and Measurement Instruments

3.4. Main Results of the Interventions

3.5. Main Limitations of the Included Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease |

| PRISMA-ScR | PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews |

| OT | Occupational Therapy |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Onyeaka, H.; Anumudu, C.K.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Egele-Godswill, E.; Mbaegbu, P. COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of the Global Lockdown and Its Far-Reaching Effects. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 368504211019854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, G.K.; Gandhi, S.; Sivakumar, T. Experiences of the Occupational Therapists During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. Ment. Health 2024, 11, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, B.P.; Mahajan, K.R.; Bermel, R.A.; Hellisz, K.; Hua, L.H.; Hudec, T.; Husak, S.; McGinley, M.P.; Ontaneda, D.; Wang, Z.; et al. Multiple Sclerosis Management during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mult. Scler. 2020, 26, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralidar, S.; Ambi, S.V.; Sekaran, S.; Krishnan, U.M. The Emergence of COVID-19 as a Global Pandemic: Understanding the Epidemiology, Immune Response and Potential Therapeutic Targets of SARS-CoV-2. Biochimie 2020, 179, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochani, R.; Asad, A.; Yasmin, F.; Shaikh, S.; Khalid, H.; Batra, S.; Sohail, M.R.; Mahmood, S.F.; Ochani, R.; Hussham Arshad, M.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: From Origins to Outcomes. A Comprehensive Review of Viral Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Management. Infez. Med. 2021, 29, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khunti, K.; Valabhji, J.; Misra, S. Diabetes and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Diabetologia 2023, 66, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Sánchez, F.; Basto-Abreu, A.; Torres-Alvarez, R.; Canto-Osorio, F.; González-Morales, R.; Dyer-Leal, D.D.; López-Ridaura, R.; Zaragoza-Jiménez, C.A.; Rivera, J.A.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Fraction of COVID-19 Hospitalizations and Deaths Attributable to Chronic Diseases. Prev. Med. 2022, 155, 106917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.M.; Berger, M.J.; Doherty, C.; Anastakis, D.J.; Baltzer, H.L.; Boyd, K.U.; Bristol, S.G.; Byers, B.; Chan, K.M.; Cunningham, C.J.B.; et al. Recommendations for Patients with Complex Nerve Injuries during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021, 48, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, B.; Fong, K.N.K.; Meena, S.K.; Prasad, P.; Tong, R.K.Y. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown on Occupational Therapy Practice and Use of Telerehabilitation—A Cross Sectional Study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 3614–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.R.; Koverman, B.; Becker, C.; Ciancio, K.E.; Fisher, G.; Saake, S. Lessons Learned From the COVID-19 Pandemic: Occupational Therapy on the Front Line. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 75, 7502090010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenforde, A.S.; Borgstrom, H.; Polich, G.; Steere, H.; Davis, I.S.; Cotton, K.; O’Donnell, M.; Silver, J.K. Outpatient Physical, Occupational, and Speech Therapy Synchronous Telemedicine: A Survey Study of Patient Satisfaction with Virtual Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 99, 977–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Guarnido, A.J.; Domínguez-Macías, E.; Garrido-Cervera, J.A.; González-Casares, R.; Marí-Boned, S.; Represa-Martínez, Á.; Herruzo, C. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health via Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Zweck, C.; Naidoo, D.; Govender, P.; Ledgerd, R. Current Practice in Occupational Therapy for COVID-19 and Post-COVID-19 Conditions. Occup. Ther. Int. 2023, 2023, 5886581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung Kn, G.; Fong, K.N. Effects of Telerehabilitation in Occupational Therapy Practice: A Systematic Review. Hong Kong J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 32, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges do Nascimento, I.J.; Abdulazeem, H.; Vasanthan, L.T.; Martinez, E.Z.; Zucoloto, M.L.; Østengaard, L.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Zapata, T.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. Barriers and Facilitators to Utilizing Digital Health Technologies by Healthcare Professionals. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.; Albaum, C.; Tablon Modica, P.; Ahmad, F.; Gorter, J.W.; Khanlou, N.; McMorris, C.; Lai, J.; Harrison, C.; Hedley, T.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health and Wellbeing of Caregivers of Autistic Children and Youth: A Scoping Review. Autism Res. 2021, 14, 2477–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Murray, L. Perinatal Mental Health and Women’s Lived Experience of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review of the Qualitative Literature 2020–2021. Midwifery 2023, 123, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Huang, W.; Pan, H.; Huang, T.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y. Mental Health During the Covid-19 Outbreak in China: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1033–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideli, L.; Lo Coco, G.; Bonfanti, R.C.; Borsarini, B.; Fortunato, L.; Sechi, C.; Micali, N. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown on Eating Disorders and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021, 29, 826–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Riedel-Heller, S.; Zürcher, S.J. Mental Health Problems in the General Population during and after the First Lockdown Phase Due to the SARS-Cov-2 Pandemic: Rapid Review of Multi-Wave Studies. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, U.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Franco, M.; Moreno, C.; Parellada, M.; Arango, C.; Fusar-Poli, P. The Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Child and Adolescent Mental Health: Systematic Review. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 32, 1151–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sessford, J.D.; Dodwell, A.; Elms, K.; Gill, M.; Premnazeer, M.; Scali, O.; Roque, M.; Cameron, J.I. Factors Associated with Mental Health Outcomes among Family Caregivers to Adults with COVID: A Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safieh, J.; Broughan, J.; McCombe, G.; McCarthy, N.; Frawley, T.; Guerandel, A.; Lambert, J.S.; Cullen, W. Interventions to Optimise Mental Health Outcomes During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 20, 2934–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4; Cochrane: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal Database Combinations for Literature Searches in Systematic Reviews: A Prospective Exploratory Study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the Extraction, Analysis, and Presentation of Results in Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Won, J.J.; Ko, J.Y. Psychological Rehabilitation for Isolated Patients with COVID-19 Infection: A Randomized Controlled Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Ko, J.Y.; Hong, I.; Jung, M.-Y.; Park, J.-H. Effects of a Time-Use Intervention in Isolated Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Randomized Controlled Study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H.; Ko, J.Y. Depression, Anxiety and Insomnia among Isolated Covid-19 Patients: Tele Occupational Therapy Intervention vs. Conventional One: A Comparative Study. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaby, D.R.; Avery, L.; Palisano, R.J.; Levin, M.F.; Khayargoli, P.; Hsieh, Y.-H.; Gorter, J.W.; Teplicky, R. BEYOND Consultant Team Environment-Based Approaches to Improve Participation of Young People with Physical Disabilities during COVID-19. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2024, 66, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhan Çelik, S.; Özkan, E.; Bumin, G. Effects of Occupational Therapy via Telerehabilitation on Occupational Balance, Well-Being, Intrinsic Motivation and Quality of Life in Syrian Refugee Children in COVID-19 Lockdown: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2022, 9, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørkedal, S.-T.B.; Bejerholm, U.; Hjorthøj, C.; Møller, T.; Eplov, L.F. Meaningful Activities and Recovery (MA&R): A Co-Led Peer Occupational Therapy Intervention for People with Psychiatric Disabilities. Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leive, L.; Melfi, D.; Lipovetzky, J.; Cukier, S.; Abelenda, J.; Morrison, R. Program to Support Child Sleep from the Occupational Therapy Perspective during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2024, 122, e202303029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gately, M.E.; Metcalf, E.E.; Waller, D.E.; McLaren, J.E.; Chamberlin, E.S.; Hawley, C.E.; Venegas, M.; Dryden, E.M.; O’Connor, M.K.; Moo, L.R. Caregiver Support Role in Occupational Therapy Video Telehealth: A Scoping Review. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2023, 39, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott-Gaffney, C.R.; Gafni-Lachter, L.; Cason, J.; Sheaffer, K.; Harasink, R.; Donehower, K.; Jacobs, K. Toward Successful Future Use of Telehealth in Occupational Therapy Practice: What the COVID-19 Rapid Shift Revealed. Work 2022, 71, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veras, M.; Sigouin, J.; Auger, L.-P.; Auger, C.; Ahmed, S.; Boychuck, Z.; Cavallo, S.; Lévesque, M.; Lovo, S.; Miller, W.C.; et al. A Rapid Review of Ethical and Equity Dimensions in Telerehabilitation for Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2025, 22, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, M.M.H.; Subroto, S.; Chowdhury, N.; Koch, K.; Ruttan, E.; Turin, T.C. Dimensions and Barriers for Digital (in)Equity and Digital Divide: A Systematic Integrative Review. DTS. 2025, 4, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, S.; Mirzakhany, N.; Dehghani, S.; Pashmdarfard, M. The Use of Tele-Occupational Therapy for Children and Adolescents with Different Disabilities: Systematic Review of RCT Articles. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran. 2023, 37, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S.M.; Egan, B.E.; Seber, J. Activity- and Occupation-Based Interventions to Support Mental Health, Positive Behavior, and Social Participation for Children and Youth: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74, 7402180020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoe, D.J.; Han, A.; Anderson, A.; Katzman, D.K.; Patten, S.B.; Soumbasis, A.; Flanagan, J.; Paslakis, G.; Vyver, E.; Marcoux, G.; et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumi, S.; Provenzi, L.; Gardani, A.; Aramini, V.; Dargenio, E.; Naboni, C.; Vacchini, V.; Borgatti, R. Engaging with Families through On-line Rehabilitation for Children during the Emergency (EnFORCE) Group Rehabilitation Services Lockdown during the COVID-19 Emergency: The Mental Health Response of Caregivers of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 43, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, S.; Sahu, P.K.; Reed, W.R.; Ganesh, G.S.; Goyal, R.K.; Jain, S. Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Mental Health and Perceived Strain among Caregivers Tending Children with Special Needs. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2020, 107, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh, A.; Dehghanizadeh, M.; Maroufizadeh, S.; Amini, M.; Shamili, A. Predictors of Mental Health among Parents of Children with Cerebral Palsy during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Iran: A Web-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 112, 103890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisticò, V.; Bertelli, S.; Tedesco, R.; Anselmetti, S.; Priori, A.; Gambini, O.; Demartini, B. The Psychological Impact of COVID-19-Related Lockdown Measures among a Sample of Italian Patients with Eating Disorders: A Preliminary Longitudinal Study. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021, 26, 2771–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flückiger, C.; Del Re, A.C.; Wampold, B.E.; Horvath, A.O. The Alliance in Adult Psychotherapy: A Meta-Analytic Synthesis. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Stone, S.J.; Heckman, T.G.; Anderson, T. Zoom-in to Zone-out: Therapists Report Less Therapeutic Skill in Telepsychology versus Face-to-Face Therapy during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychotherapy 2021, 58, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoyne, N.; Cohn, A.S. Lessons from the Transition to Relational Teletherapy During COVID-19. Fam. Process 2020, 59, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, S.G.; Fuhrel-Forbis, A.; Rogers, M.A.M.; Eggly, S. Association between Nonverbal Communication during Clinical Interactions and Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aafjes-Van Doorn, K.; Békés, V.; Luo, X.; Hopwood, C.J. Therapists’ Perception of the Working Alliance, Real Relationship and Therapeutic Presence in in-Person Therapy versus Tele-Therapy. Psychother. Res. 2024, 34, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafali, N.; Cook, B.; Canino, G.; Alegria, M. Cost-Effectiveness of a Randomized Trial to Treat Depression among Latinos. J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2014, 17, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Databases | Search Strategy 8 March 2025 | Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | “occupational therapy” [All Fields] AND “mental health” [All Fields] AND (“SARS CoV 2” [MeSH Terms] OR “SARS CoV 2” [All Fields] OR “COVID” [All Fields] OR “COVID 19” [MeSH Terms] OR “COVID 19” [All Fields]) | 276 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“occupational therapy” AND “mental health” AND COVID) | 129 |

| Embase | (‘occupational therapy’/exp OR ‘occupational therapy’) AND (‘mental health’/exp OR ‘mental health’) AND (‘covid’/exp OR COVID) | 375 |

| Web of Science | “occupational therapy” AND “mental health” AND COVID (Topic) | 118 |

| OTSeeker | [Any Field] like ‘“occupational therapy”’ AND [Any Field] like ‘“mental health”’ AND [Any Field] like ‘COVID’ | 0 |

| PsycINFO | “occupational therapy” AND “mental health” AND COVID | 120 |

| Author, Year | Design | Participants | Recruitment Period | Intervention/Comparator | Study Outcomes (Evaluation Tool) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jung et al., 2022 [31] | RCT | 109 isolated adult patients with COVID-19 (IG mean age: 51.06 years; CG mean age: 45.96 years) | From 27 May to 17 September 2021 | Psychological rehabilitation program (n = 57)/conventional medical care (n = 52) | Anxiety (SAS, VAS). Depression (VAS, SDS, PHQ-9). Insomnia (ISI-K). |

| Belhan Çelik et al., 2022 [35] | RCT | 52 refugee children aged between 13 and 15 years (IG mean age: 13.5 years; CG mean age: 13.5 years) | From 13 December to 31 December 2020 | Online classes + OT via telerehabilitation (n = 26)/only online classes (n = 26) | Occupational Balance (OBQ11). Quality of life (PedsQL). Well-being (WSS). Intrinsic Motivation (IMS). |

| Bjørkedal et al., 2023 [36] | RCT | 139 adults with psychiatric disabilities (IG mean age: 42 years; CG mean age: 44 years) | From September 2018 to August 2020 | Meaningful activities and recovery (MA&R) + standard mental health care (n = 70)/only standard mental health care (n = 69) | Occupational engagement (POES-S). Functioning (WHODAS 2.0). Personal recovery (QPR). Quality of life (MANSA, EQ-5D-5L). |

| Jung et al. 2023 [32] | RCT | 41 adult patients with COVID-19 (IG mean age: 47.37 years; CG mean age: 58.59 years) | From 1 February to 19 March 2021 | Time use intervention + standard care (n = 19)/self-activity education + standard care (n = 22) | Occupational balance (K-LBI). Anxiety (SAS). Depression (PHQ-9). Boredom (MSBS-8). Insomnia (ISI-K). Quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF). Fear of COVID-19 (FCV-19S) |

| Anaby et al., 2024 [34] | nRCT | 21 adolescents and young adults with physical disabilities (mean age: 21 years) | From August 2020 to November 2021 | Pathways and resources for engagement and participation (PREP) (n = 21)/NA | Activity performance and satisfaction (COPM). Cognitive and affective functions (BASC-3). Motor functions (Trunk Impairment Scale, VAS, Goniometry, dynamometer, Finger dexterity test, Functional reach test, Berg Balance Scale and One-leg standing). |

| Leive et al., 2024 [37] | nRCT | 30 children aged 3–10 years with neurodevelopmental disorder and insomnia (mean age: NS) | From June 2020 to September 2021 | Program to support child sleep from the occupational therapy perspective [Programa de Acompañamiento al Sueño en la Infancia desde Terapia Ocupacional] (PASITO) (n = 22)/waiting list group (n = 8) | Sleep (SHQ, CSD). |

| Jung et al., 2024 [33] | RCT | 40 adult patients with COVID-19 (IG mean age: 53.58 years; CG mean age: 49.06 years) | From 18 November 2021 to 7 April 2022 | Psychiatric tele-rehabilitation program (n = 24)/conventional psychiatric rehabilitation (n = 16) | Anxiety (SAS, VAS). Depression (VAS, PHQ-9). Boredom (MSBS-8). Insomnia (ISI-K). Quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF). |

| Author, Year | Intervention | Intervention Description | Intervention Duration | Professionals Involved in the Intervention | Main Results of the Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jung et al., 2022 [31] | In-person: psychological rehabilitation program in adults | An intervention consisting of education, craft activities, and physical activity. The education part included information about COVID-19. Craft activities included knitting, cross-stitching with jewelry, coloring, or block making. Physical activities included stretching, strength training, and breathing exercises. | Step 1: 20 min. Step 2: NS. Step 3: 8 days, 20 min per day (craft activities) and 8 days, 20 min per day (physical activity). | OT, nurse physician, psychiatrist, PT | IG and CG improved their levels of anxiety, depression, and insomnia after the interventions. Significantly decreased levels of anxiety, depression, and insomnia in IG vs. CG. |

| Belhan Çelik et al., 2022 [35] | Telerehabilitation: online classes + OT via telerehabilitation in children | Online classes: remote classes trough the Ministry of National Education Online Education Platform (EBA) as part of the children’s routine education plan. OT via telerehabilitation: it included both group and individual activities. Group activities were painting, sports, or games trough Zoom. Individual activities included routines and daily occupations organized in a balanced way; MentalUp application also used. | 15 sessions, 3 weeks. Five 1 h session per week. | Investigator, OT | IG improved their occupational balance, well-being, intrinsic motivation, and health-related quality of life after the interventions. Only CG showed a significant decrease in the psychosocial health score after the intervention. Significantly improved occupational balance, well-being, intrinsic motivation, and health-related quality of life in IG vs. CG. |

| Bjørkedal et al., 2023 [36] | In-person: MA&R + standard health in adults | MA&R: Module I with two weekly sessions focusing on recognizing and exploring meaningful activities, and module II with two monthly sessions allowing participants to engage in new meaningful activities at their own pace. In addition, optional individual support to engage in activities was also offered. Standard mental health: The multidisciplinary Flexible Assertive Community Treatment model provided by Community Mental Health Services. | 22 sessions, 8 months. Eleven group 90 min sessions and eleven individual 30–60 min sessions. | OT, peer worker | IG and CG improved their activity engagement, quality of life, and functioning after the interventions. They found no improvement in health-related quality of life in any of the groups. Only IG improved their personal recovery after the intervention. IG vs. CG: No significant differences were found between groups in activity participation, functioning, personal recovery, or quality of life after the interventions. |

| Jung et al., 2023 [32] | In-person: Time-use intervention + standard care | Patients and therapists analyzed daily activities in face-to-face sessions, selected meaningful occupations based on assessments, created timetables, and practiced selected tasks with therapist support and materials provided. Standard care included antiviral therapy for COVID-19. | A 7-day time-use intervention of four steps. Daily sessions. | OT | IG and CG reduced their depression and fear of coronavirus levels. Only CG showed significant reductions in boredom. IG vs. CG: IG had better results in occupational balance, insomnia, and quality of life. |

| Anaby et al., 2024 [34] | Telerehabilitation: PREP in adolescents and young adults | PREP is an individual-based intervention with five steps (make goals; map out a plan; make it happen; measure the process and outcomes; move forward), which focuses on modifying the environment. An OT met individually with each participant via video call to select a goal for participation in a leisure activity. The OT worked collaboratively with each participant to seek and create opportunities for participation in the chosen activity and to identify and remove potential environmental barriers for participation in that activity. | 8-week self-chosen leisure activity at their home or community. | OT | An improvement in performance and satisfaction with chosen activities was observed after the intervention. A decrease in depression, anxiety, social stress, and hyperactivity was observed after the intervention. An improvement in at least one domain of body function occurred in 10 participants for motor outcomes. |

| Leive et al., 2024 [37] | Telerehabilitation: PASITO in children | The intervention objectives were based on the essential characteristics of sleep as an occupation promoting the implementation of adaptive and maladaptive strategies and sleep hygiene strategies adapted to the interests of each child and their primary caregivers. This intervention was remote, intensive, and individualized, coordinated by OTs and mediated by parents. The strategies were caregiver care, pleasant experiences, daily organization, routines and rituals, and rest. | Program of 19 days. Sessions of 3.5 h and/or 45 min. | OT, parents | IG improved their overall sleep, bedtime resistance, sleep onset, sleep duration, sleep anxiety, and night waking after the intervention. No significant changes in sleep were found in the CG after the intervention. |

| Jung et al., 2024 [33] | Telerehabilitation: psychiatric telerehabilitation program | Telephone-based telerehabilitation. Patients selected and performed daily 50 min meaningful activities (e.g., physical, craft, or leisure) with OT guidance. OTs provided remote support and monitored progress via daily phone calls, without direct contact. | Program of 7 days. Individual sessions of 50 min per day. | OT | IG and CG improved their quality of life and anxiety. Only CG showed significant reductions across all psychological distress measures. IG vs. CG: IG had higher levels of anxiety and depression. |

| Author, Year | Main Limitations | Funding/Support | Conflicts of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jung et al., 2022 [31] | -Results may not reflect information from all patients, causing selection bias. -There were no baseline assessments of anxiety and depression levels. -Findings may be generalized to Korean patients, but they may be not applicable to other countries. -No follow-up of patients after discharge. | This research was supported by the Accountable Care Hospital Connected Care (ACHCC) Project funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea (Project Number: 2022-ACHCC-L26). | None declared. |

| Belhan Çelik et al., 2022 [35] | -The intervention period was relatively short. -Authors did not assess the impact of their favorable results on learning ability or school success. -The activities used in the intervention were limited. | The authors received no financial support. | None declared. |

| Bjørkedal et al., 2023 [36] | -No blinding of participants or staff to intervention allocation. -Outcome measures consisted of self-report instruments that are more prone to bias. -Outcomes were only measured at baseline and after the intervention. -Low generalizability of the results. The trial was partially conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and results may be unique to this setting. -No specific data were obtained on participants’ use of services relative to standard mental health care, nor on the type of care participants received. | The Tryg Foundation (ID number 112526), the Research Foundation of the Danish Occupational Therapy Association (FF 117 R45 A1271), and a grant from the Mental Health Services of the Capital Region of Denmark sponsored the RCT. | None declared. |

| Jung et al., 2023 [32] | -Small sample size. -Study conducted at a single center; therefore, the results cannot be generalized. -Self-reported questionnaires were used as outcome measurements. -The possibility of socially desirable responses, recall bias, and misunderstanding of questions cannot be excluded. -Follow-up after discharge was not performed. -The non-blinded trial design could have caused performance bias and detection bias. | This research was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021S1A3A2A02096338) | None declared. |

| Anaby et al., 2024 [34] | -Low generalizability of the results. Only participants with physical disabilities and without intellectual delay were included. -Participants were not randomly assigned. -Exploratory analysis of the impact of functional limitations and mental health problems were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. | Institute of Human Development, Child and Youth Health of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Grant Number: 166213 | None declared. |

| Leive et al., 2024 [37] | -Objective measures were not used. -The sleep habits questionnaire has not been validated in the Argentine population. -The small sample size, which does not guarantee generalization of the results. -The time availability of the caregivers and internet connection may imply a bias in terms of families having a high-income level. -The small size of the control group made comparison with the intervention group difficult. | The authors received no financial support. | None declared. |

| Jung et al., 2024 [33] | -Small sample size. -Patients’ baseline mental health scores were unknown. -The PHQ-9 score in the intervention group at admission was significantly higher than the corresponding score in the control group. -Self-reported evaluation scale was used in this study. -Recall bias, misinterpretations, and socially desirable responses cannot be ruled out. | This research was supported by the Accountable Care Hospital Connected Care (ACHCC) Project funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea (Project Number:2024-ACHCC-L26). | None declared. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Compañ-Gabucio, L.-M.; Moreno-Morente, G.; Company-Devesa, V.; Torres-Collado, L.; García-de-la-Hera, M. Occupational Therapy Interventions in Mental Health During Lockdown: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172136

Compañ-Gabucio L-M, Moreno-Morente G, Company-Devesa V, Torres-Collado L, García-de-la-Hera M. Occupational Therapy Interventions in Mental Health During Lockdown: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172136

Chicago/Turabian StyleCompañ-Gabucio, Laura-María, Gema Moreno-Morente, Verónica Company-Devesa, Laura Torres-Collado, and Manuela García-de-la-Hera. 2025. "Occupational Therapy Interventions in Mental Health During Lockdown: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172136

APA StyleCompañ-Gabucio, L.-M., Moreno-Morente, G., Company-Devesa, V., Torres-Collado, L., & García-de-la-Hera, M. (2025). Occupational Therapy Interventions in Mental Health During Lockdown: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(17), 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172136