Perceptions and Attitudes of Informal Caregivers of Stroke Patients Regarding the Stroke-CareApp: A Phenomenological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Theoretical Perspective

2.3. Participants

- -

- Agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consent form.

- -

- Informal caregivers of stroke patients with a Barthel index < 60.

- -

- Have a smartphone and know how to use it.

- -

- Over 18 years of age.

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Stroke-CareApp

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

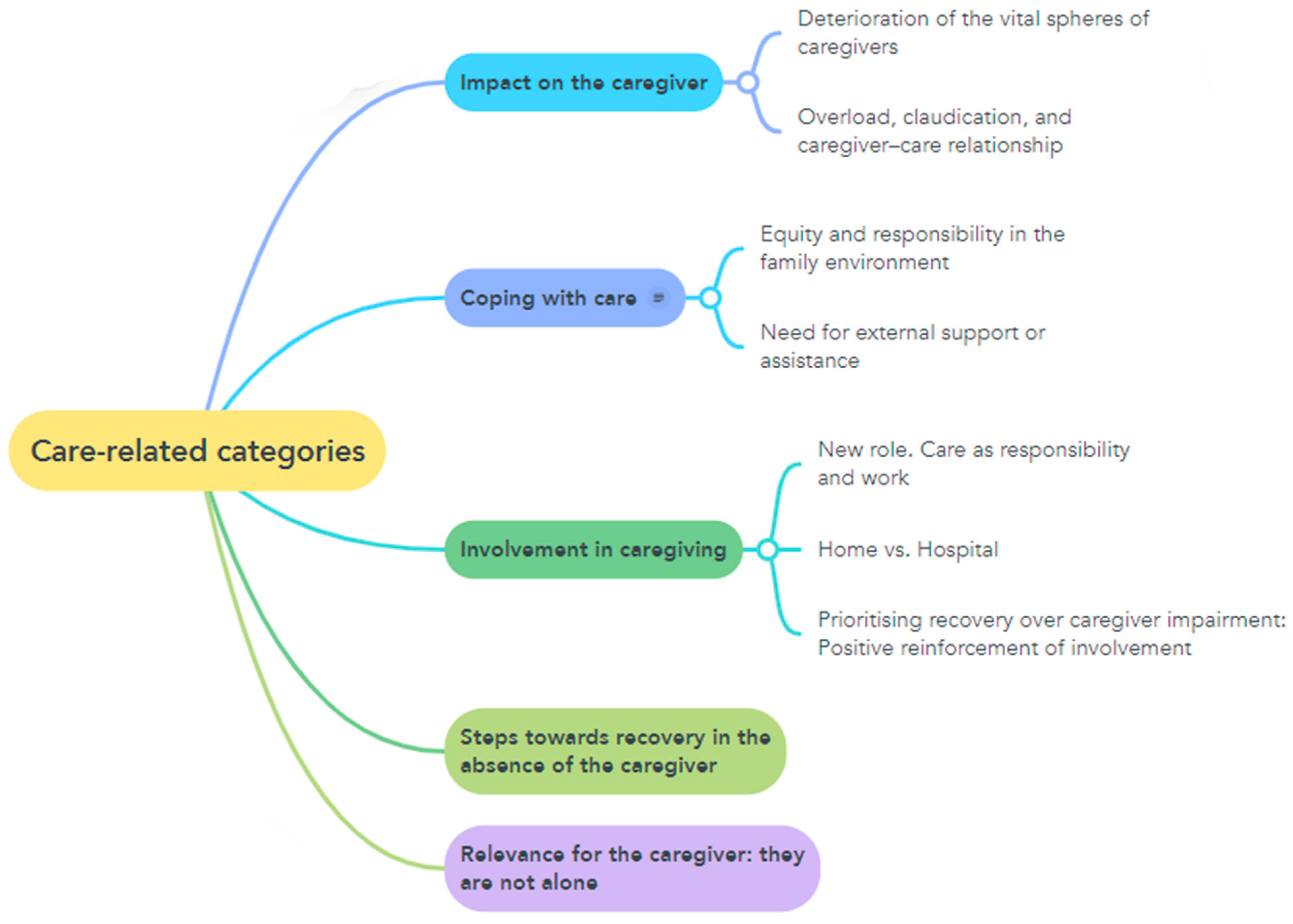

3. Results

3.1. Coping with Caregiving

3.1.1. Equity and Responsibility in the Family Environment

Well, it’s good for now because the three brothers are taking turns and when one goes, another one comes, and we do it. While one has no work, he comes and substitutes for the other. Now there is one who is on vacation, while the other has started working so we alternate. One sleeps there some days, the other one sleeps there other days, and depending on how things go and the time needed, we do it…C2

Look, we are three siblings, and there is my older brother, who is the one who has taken care of my dad the most because I left, I went to Mexico because my sister is working there. So I was there the first month that everything happened, that we were admitted, and the second month and the third month my brother took care of it because I was away. So, I came back in mid-February and now it’s my turn…C3

3.1.2. Need for External Support or Assistance

My partner and I are alone, but we are lucky enough to work from home, so we can be at home and have some freedom in our schedules. When there is an event, we have to ask someone to stay with her so that we can do it…C1

It breaks our hearts to leave her alone because she can’t even press the button to call the nurse (…). So, of course, since life goes on and we all have to continue working, in the end what we do is to hire a non-professional caregiver…C5

3.2. Impact on the Caregiver

3.2.1. Deterioration of the Vital Spheres of Caregivers

Radically in all spheres of my life. At the family level, because I hardly see my children. I have already told my friends not to be angry with me, that I will come back someday because I don’t have so much time. On an economic level, we had to fix the apartment because, of course, my mother was a very hard-working and independent person. And of course, all of a sudden, we realized that she couldn’t go back home just like that. So we had to buy crane beds…C5

And the work that I have has been cut back because I used to work from 9 am to 5 pm, and now I work from 8 am to 2:30 pm. I have a relationship with a woman who lives in Bilbao, and she has also been affected. Well, in general, my diet has worsened, I don’t know anymore…C4

3.2.2. Overload, Claudication, and Caregiver–Care Relationship

I have almost no time for myself or to do my own things anymore. That is to say, having to be very limited in time, because of course, you have to change it three times, you have to give the food…C1

The truth is that for my brother it has been very good because it has increased his confidence in my father. With my brother, their communication and empathy with each other have improved a lot. That has improved a lot. It’s the same with me because me and my dad have always lived together, and we already knew each other…C3

On an emotional level, it does make me sad to see her like this, because she wouldn’t want to be like this, always talking to her. But look, these are things that you don’t decide, and you have to go on…C2

I find myself permanently very tired…C4

3.3. Involvement in Caregiving

3.3.1. New Role: Care as Responsibility and Work

If you go out, you are always on the lookout, you have to come back, even if Pedro is there. But there are things that I have to do…C1

And well, I work in the morning and come here in the afternoon, every month, seven days a week, coming here and taking care of my mother is a job in itself…C4

But during the day, we are there all the time, we do all the hygiene, we change her diaper with my sister and my brother or the caregiver. Well, we do the postural changes, we are with her, we feed her, we give her dinner, everything…C5

3.3.2. Home Versus Hospital

Because it seems like I have also become very involved in the issue of changing it, of learning… because I think I have to learn how to do these things. I don’t know, maybe I don’t need it, but if I need it, I’d better learn it already, right?…C4

So, all I do is look for information to help my mother. Because of course, I’m not a doctor, and I don’t know much about it either. So I look for speech therapist videos to see what I can do to help her recover her voice. Also, with a view to the fact that I imagine that in two or three weeks we will be discharged, and then when we get home, I will be able to find out things…C5

3.3.3. Prioritizing Recovery over Caregiver Impairment: Positive Reinforcement of Involvement

So, I take it as my time is invested in my mother’s recovery. And well, if it costs me a physical or mental effort, well, I assume it…C4

From time to time I don’t have the obligation to go, in quotation marks, right? From 3.30 pm to 10.00 pm at night, but I always go for a few hours…C5

3.4. Steps Toward Recovery in the Absence of the Caregiver

Her level of dependency is so high… The orderlies come in the morning, and after we do her hygiene, the orderlies come and sit her in the chair she has, and we put her on the bed, but she can’t do anything. She has lost all mobility with the hemiplegia on the left side…C5

She gets up from the chair and goes to bed. But well, this week she has already taken a big leap because she was starting to walk between bars and well, the truth is that she is in better spirits. Her speech is affected, and her memory is still a little bit there… quite resentful…C4

He now showers by himself, tidies his bathroom by himself… He is in a wheelchair, but they have already given him a cane so that, with company, he can walk little by little, and he is in this process. He eats alone and speaks well and is starting to write with the hand he could not, and he is with the speech therapist. The physiotherapy has been going very well. The only thing that is failing him is a little bit his memory…C3

She is moving around a bit because she is eager to walk and go down to the street. She has a lot of willpower. She is always moving, but of course, she has the limitation she did not have before, right? I mean, for example, she can walk around the house with her walker. But we have to keep an eye on her…C1

3.5. Relevance for the Caregiver: They Are Not Alone

Those caregivers sometimes find themselves alone or helpless in circumstances (…) And of course, at that moment you say: How difficult can this person’s life be, right? I think we have to remember the caregivers, because that also benefits the healthcare system…C4

Of course, support is needed for the caregivers because they do not prepare you for this…C2

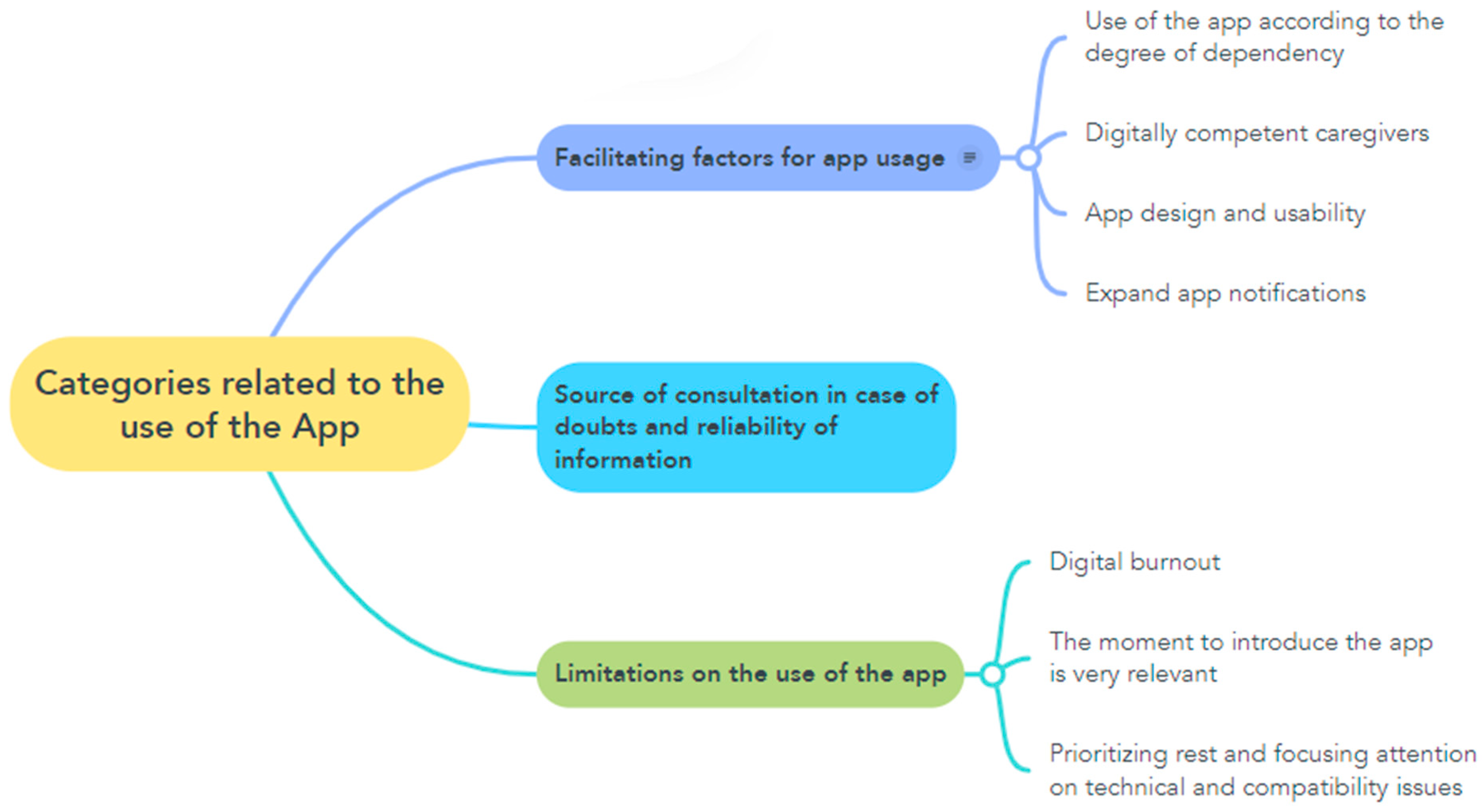

3.6. Facilitating Factors for App Usage

3.6.1. Use of the App According to the Degree of Dependency

A stroke does not affect everyone in the same way, because I understand that it is not the same if you have a stroke when you are 40 years old, if you are 82 years old, if you are 60 years old, or if you have previous pathologies or not. So, it is very difficult for you to know what will happen in each case. Although I consider that in my circumstances it may have been a little early because we are involved in a process that can take months and in the case of a young patient, who has the prospect of recovering much more quickly because he has also been caught earlier…, he will recover much sooner. Well, it is true that the moment at which you do it is correct. I understand that there must be hundreds of cases, right? I think it is better to err on the side of too early than too late…C4

3.6.2. Digitally Competent Caregivers

Yes, yes, yes, yes, the cellphone is like a computer, and I use it for everything…C3

Yes, well, besides, because of my job I have to do part of my working day from my cellphone, so, well, I send emails, I use it like any other teenager, but I am able to do any kind of business on my cellphone…C4

Let’s see, I use it to call, obviously… What I use it more for right now is chatting with my siblings. And then to look at the newspaper if I have a minute, I like to find out what’s going on in the world to browse the paper and that’s it. And few purchases, I can’t afford…C5

3.6.3. App Design and Usability

I thought it was easy. What I saw seemed easy, that’s for sure. I mean, to handle because I went in to look at some things when I was in the hospital, and it seemed like an easy application because there are some that are a bit of a mess, and it says whew, I’ll pass and the only thing I can tell you is that I found it a bit easy to handle…C1

Yes, it was easy. I mean, if you have a little bit of intuition, it’s easy to use…C2

No, it works well. If you have a little bit of basic telephone handling, which everybody has, I don’t see it as difficult…C4

3.6.4. Expanded App Notifications

If that is the case, I think it is very good that a few months have passed and that you contact me so that I know that, although I have not used it, is still there…C4

For example, this happens to me with Sanitas, sometimes I get an email with information, healthy food and then you click on it, you know, because I’m going to click on it as a reminder, right? And you see a little bit if… maybe you remember that you have it or something and then you click on it out of curiosity, like a reminder that you have it…C1

Maybe now that I’m talking to you I’ll bring the phone home so I can use it…C5

3.7. Source of Consultation in Case of Doubts and Reliability of Information

I learned quite a lot at the hospital because I spent practically a month there, and I learned quite a lot from what the nurses were doing because I applied myself quite a lot and then I didn’t need much more either…C2

I appreciated it because, well, it is also a way of having the information biased in the same place where you can go and look for it, because at the beginning it was like well, I am going to look to see what is stroke, what are the consequences or… sometimes on the Internet you know that when you search you find what you do not want or what you want to see exactly things you want to see that maybe are not relevant or that is not about the disease itself…C5

But it is true that when I have a doubt I have always turned to the people who are here, and I think it is silly to go to the Internet, don’t you? If you can raise your head and talk to a real person…C4

I have looked at YouTube for more information, and I have been taking advice from there. Then, between what I’ve read on the Internet and the videos I’ve seen, I’ve been taking notes. I have also read articles on the Internet and then nursing videos. In addition, a nurse comes to visit me (…) and all the doubts I have had have also been solved…C2

3.8. Limitations on the Use of the App

3.8.1. Digital Burnout

But sometimes because of laziness, and also because I’m tired of my cell phone from working and then I don’t feel like going to the computer again and again…C1

3.8.2. The Moment to Introduce the App Is Very Relevant

And I looked a little bit over, but I was still in the hospital. And I say, well, when I get home I’ll have more doubts and it will be more necessary…C1

No, because I didn’t think it was necessary either. No, there wasn’t much to ask. Actually, since I had been informed by other places in the hospital, I didn’t see the need to ask about things that I had already been informed about. When I am at home, and suddenly I have a question and I no longer have the nurses, the doctors, the therapists next to me, then that will be the moment when I say look, I am going to remember the app, and then I am sure that it will solve things for me…C2

You know what happens? In the first month or the first few days, there are many things to do looking for everything to go well and you don’t pay attention to the application, but I tell you that after that, yes, I did. When all that happened, I got home, I dropped the papers and honestly I didn’t pick it up again until… well it was my dad’s month, which was harder…C3

I understand that it is an application more focused on the caregiver when it is in a more home context, right? And from a personal point of view, that is, in my specific case, yes, it may be a bit early… C4C4

3.8.3. Prioritizing Rest and Focusing Attention on Technical and Compatibility Issues

When I go to my cellphone, I have the application there. What I don’t have time for, that’s it. And well, your entry at the beginning, but the truth is that I have almost no time for anything. So of course, sometimes I have to spend a little time wasting time on something, don’t you understand?C1

It’s just that between the fact that I have a lot of busy time and sometimes I don’t have much time to think. I’m thinking all day long. I need this, I need that, I have to go shopping…C2

These last two months I haven’t even remembered. Too many things on my mind, I guess, and I had totally erased…C5

But since I’m not at home either. Now the last thing I want to do when I get home, when I’m exhausted, is to spend my time with stuff…C4

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fundación Telefónica. Sociedad Digital en España 2023 [Internet]; Fundación Telefónica: Madrid, Spain, 2023; Available online: https://publicaciones.fundaciontelefonica.com/api/view/publication/sociedad-digital-en-espana-2023/1472?country=Espa%C3%B1a (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Bernal, Z.V.; Rodríguez, M.L.; Mujica, G.B. Aplicaciones Móviles en Salud, una Revisión Sistemática Cualitativa [Internet]. Optometría. 1 January 2021. Available online: https://ciencia.lasalle.edu.co/items/3215e168-bb64-4265-9985-8b16d392eec (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Andrades-González, I.; Romero-Franco, N.; Molina-Mula, J. e-Health as a tool to improve the quality of life of informal caregivers dealing with stroke patients: Systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 790–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Estrategia en Ictus del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Actualización 2024 [Internet]; Ministerio de Sanidad: Madrid, Spain, 2025; Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/calidadAsistencial/estrategias/ictus/docs/Estrategia_en_Ictus_del_SNS._Actualizacion_2024_accesible.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Rodríguez Prunotto, L.; Cano de la Cuerda, R. Aplicaciones móviles en el ictus: Revisión sistemática. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 66, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Rodríguez, M.T.; Collado Vázquez, S.; Martín Casas, P.; Cano de la Cuerda, R. Neurorehabilitation and apps: A systematic review of mobile applications. Neurological (Engl. Ed.) 2018, 33, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICTUSCAT—Fundación Ictus [Internet]. Available online: https://www.fundacioictus.com/projectes/ictuscat/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- La aplicación “Vivir en Casa” Amplía Funciones para Facilitar la Autonomía de Personas Dependientes|Sociedad|Cadena SER [Internet]. Available online: https://cadenaser.com/andalucia/2025/08/01/la-aplicacion-vivir-en-casa-amplia-funciones-para-facilitar-la-autonomia-de-personas-dependientes-ser-malaga/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Digitalizando el Cuidado: Aplicaciones para el Cuidado de Persona [Internet]. Available online: https://www.expomedhub.com/nota/innovacion/apps-tecnologia-que-ayuda-a-los-cuidadores-de-pacientes-con-enfermedades-graves?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Denham, A.M.J.; Wynne, O.; Baker, A.L.; Spratt, N.J.; Turner, A.; Magin, P.; Janssen, H.; English, C.; Loh, M.; Bonevski, B. “This is our life now. Our new normal”: A qualitative study of the unmet needs of carers of stroke survivors. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodford, J.; Farrand, P.; Watkins, E.R.; LLewellyn, D.J. “I Don’t Believe in Leading a Life of My Own, I Lead His Life”: A Qualitative Investigation of Difficulties Experienced by Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors Experiencing Depressive and Anxious Symptoms. Clin. Gerontol. 2018, 41, 293–307. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29185911/ (accessed on 22 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.F.d.; Gomes, T.M.; Viana, L.R.d.C.; Martins, K.P.; Costa, K.N.d.F.M. Stroke: Patient characteristics and quality of life of caregivers. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2016, 69, 933–939. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27783737/ (accessed on 22 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bakas, T.; Farran, C.J.; Austin, J.K.; Given, B.A.; Johnson, E.A.; Williams, L.S. Stroke caregiver outcomes from the Telephone Assessment and Skill-Building Kit (TASK). Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2009, 16, 105–121. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19581197/ (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, L.L.; Steiner, V.L.; Khuder, S.A.; Govoni, A.L.; Horn, L.J. The effect of a Web-based stroke intervention on carers’ well-being and survivors’ use of healthcare services. Disabil. Rehabil. 2009, 31, 1676–1684. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19479528/ (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, E.; Cheon, J.; Chung, S.; Moon, S.; Moon, K. The effectiveness of home-based individual tele-care intervention for stroke caregivers in South Korea. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 369–375. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22897188/ (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Possin, K.L.; Merrilees, J.J.; Dulaney, S.; Bonasera, S.J.; Chiong, W.; Lee, K.; Hooper, S.M.; Allen, I.E.; Braley, T.; Bernstein, A.; et al. Effect of Collaborative Dementia Care via Telephone and Internet on Quality of Life, Caregiver Well-being, and Health Care Use: The Care Ecosystem Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 1658–1667. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31566651/ (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Hafsteinsdóttir, T.B.; Vergunst, M.; Lindeman, E.; Schuurmans, M. Educational needs of patients with a stroke and their caregivers: A systematic review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, 14–25. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20869189/ (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Forster, A.; Dickerson, J.; Young, J.; Patel, A.; Kalra, L.; Nixon, J.; Smithard, D.; Knapp, M.; Holloway, I.; Anwar, S.; et al. A structured training programme for caregivers of inpatients after stroke (TRACS): A cluster randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet 2013, 382, 2069–2076. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24054816/ (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Introducción a la Investigación Cualitativa, 3a ed.; Morata: Valencia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 7a ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elida Fuster Guillen Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos D. Investigación cualitativa: Método fenomenológico hermenéutico. Propósitos Y Represent. 2019, 7, 201–229. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2307-79992019000100010&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es (accessed on 9 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Perdomo, C.A. Fenomenología hermenéutica y sus implicaciones en enfermería. Index De Enfermería 2016, 25, 82–85. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1132-12962016000100019 (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Castillo Espitia, E. La fenomenología interpretativa como alternativa apropiada para estudiar los fenómenos humanos. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2000, 18, 27–35. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1052/105218294002.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Asuntos Críticos en los Métodos de Investigación Cualitativa, 1st ed.; Publicaciones Universidad de Alicante: San Vicente del Raspeig, Spain, 2003; pp. 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. Phenomenology of Practice: Meaning-Giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, K.; Dahlberg, H.; Nyström, M. Reflective Lifeworld Research, 2nd ed.; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, L. Debating Phenomenological Research Methods. Phenomenol. Pract. 2009, 3, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Teoría del Aprendizaje Social, 3a ed.; Espasa-Calpe: Madrid, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. À propos de la famille comme catégorie réalisée. Actes. Rech. Sci. Soc. 1993, 100, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.G.; Dorothea, E. Modelos Y Teoría en Enfermería, 6a ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 267–295. [Google Scholar]

- Son Espases Atiende Unos 800 Casos Anuales de Ictus|Actualidad|Cadena SER [Internet]. Available online: https://cadenaser.com/baleares/2023/10/29/son-espases-atiende-de-media-800-casos-anuales-de-ictus-radio-mallorca/ (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oak, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.D.N. El sabio manual de investigación cualitativa [Internet]. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3a ed.; Publicaciones Sage Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 793–830. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/The_SAGE_Handbook_of_Qualitative_Researc.html?id=AIRpMHgBYqIC (accessed on 11 April 2024).

- Ajzen, I. Nature and Operation of Attitudes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, H.; Aristizábal Díaz-Granados, E.T. Análisis fenomenológico interpretativo. Pensando Psicol. 2019, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrades-González, I.; Molina-Mula, J. Validation of Content for an App for Caregivers of Stroke Patients through the Delphi Method. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Albornoz, Á.L. Martin heidegger’s hermeneutic phenomenological method and the possibility of independent philosophical inquiry. Stud. Heideggeriana 2021, 10, 245–262. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Acuña, M. Comprendiendo la experiencia y las necesidades al ser cuidador primario de un familiar con enfermedad de Alzheimer: Estudio de caso. Gerokomos 2014, 25, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bierhals, C.C.B.K.; dos Santos, N.O.; Fengler, F.L.; Raubustt, K.D.; Forbes, D.A.; Paskulin, L.M.G. Needs of family caregivers in home care for older adults. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2017, 25, e2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago-Echeverri MORSEAD. Necesidades generales de los cuidadores de las personas en situación de discapacidad. Investig. En Enfermería Imagen Y Desarro. 2010, 12, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Noell Boix, R.; Ochandorena-Acha, M.; Reig-Garcia, G.; Moreno-Casbas, M.T.; Casas-Baroy, J.C. Identificación de necesidades de los cuidadores informales: Estudio exploratorio. Enfermería Glob. 2022, 21, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Claro, Y.G.; Lindarte Clavijo, A.A.; Jiménez Sepúlveda, M.A.; Vega Angarita, O.M. Características sociodemográficas asociadas a la sobrecarga de los cuidadores de pacientes diabéticos en Cúcuta. Rev. Cuid. 2013, 4, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauricio Ocampo, J.; Herrera, J.A.; Torres, P.; Alexander Rodríguez, J.; Loboa, L.; Alberto García, C. Sobrecarga asociada con el cuidado de ancianos dependientes. Colomb Med. 2007, 38, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Medina, R.M.; Landeros-Pérez, M.E. Sobrecarga del agente de cuidado dependiente y su relación con la dependencia funcional del adulto mayor [Internet]. In Enfermería Universitaria; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 11, Available online: www.elsevier.es/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Correlates of Physical Health of Informal Caregivers: A Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2007, 62, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Martínez, R.T.; Molina Cardona, E.M.; Gómez-Ortega, O.R. Intervenciones de enfermería para disminuir la sobrecarga en cuidadores: Un estudio piloto. Rev. Cuidarte. 2016, 7, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogero-García, J. Las consecuencias del cuidado familiar sobre el cuidador: Una valoración compleja y necesaria. Index Enfermería 2010, 19, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Fernández, L.; Frías-Osuna, A.; Moreno-Cámara, S.; Palomino-Moral, P.A.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Primeros momentos del cuidado: El proceso de convertirse en cuidador de un familiar mayor dependiente. Aten. Primaria 2018, 50, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas Viniegra, L. Content Analysis of Elderly Consumer and use of health apps. Rev. Comun. Y Salud 2015, 5, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, S.; Ling, R. Digital technology and caregiving: What caregivers say. N. Media. Soc. 2020, 22, 1392–1410. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M. Internet Use Among Older Adults: Association with Health Needs, Psychological Capital, and Social Capital. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2013, 15, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heart, T.; Kalderon, E. Older adults: Are they ready to adopt health-related ICT? Int. J. Med. Inform. 2013, 82, e209–e231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin-Torres, V.; Valverde Aliaga, J.; Sánchez Miró, I.; Sáenz Del Castillo Vicente, M.I.; Polentinos-Castro, E.; Garrido Barral, A. Internet as an information source for health in primary care patients and its influence on the physician-patient relationship. Aten. Primaria 2013, 45, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; Guo, X.; Li, B.; Dang, Y. Empowering Patients Using Smart Mobile Health Platforms: Evidence from A Randomized Field Experiment. MIS Q 2021, 46, 151–191. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2102.05506 (accessed on 14 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Jain, R.C.; Kankanhalli, M.S. A Comprehensive Picture of Factors Affecting User Willingness to Use Mobile Health Applications. ACM Trans. Comput. Health 2023, 5, 30. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2305.05962 (accessed on 14 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Melo de Souza, L.; Wegner, W.; Pinto Coelho Gorini, M. Health education: A strategy of care for the lay caregiver. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Boots, L.M.M.; de Vugt, M.E.; van Knippenberg, R.J.M.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Verhey, F.R.J. A systematic review of Internet-based supportive interventions for caregivers of patients with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 29, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Code | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55 | 55 | 56 | 25 | 49 |

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Female | Female |

| Educational level | Professional training | Baccalaureate | Professional training | Completed primary education | Higher education |

| Income level (EUR/month) | 2000–3000 | <500 | <500 | 500–999 | 1000–1999 |

| Cohabitation | Single | Spouse | Spouse and children | Father | Spouse and children |

| Residence | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban |

| Type of housing | Rented | Ownership | Ownership | Ownership | Ownership |

| Employment status | Professional | Self-employed | Professional | Professional | Professional |

| Relationship with the patient | Father/Mother | Son/Daughter | Son/Daughter | Son/Daughter | Son/Daughter |

| Do you receive help with the care of your relative? | Yes | Other family members | Child | Yes | Yes |

| How much help (in hours per day) do you receive? | <1 | >8 | >8 | >8 | >8 |

| Initial Barthel of the relative with stroke | 20 | 20 | 25 | 10 | 15 |

| Barthel at six months of the relative with stroke | 25 | 30 | 40 | 40 | 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andrades-González, I.; Rodríguez-Estrabot, N.; Magdaleno-Moya, R.; Molina-Mula, J. Perceptions and Attitudes of Informal Caregivers of Stroke Patients Regarding the Stroke-CareApp: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172082

Andrades-González I, Rodríguez-Estrabot N, Magdaleno-Moya R, Molina-Mula J. Perceptions and Attitudes of Informal Caregivers of Stroke Patients Regarding the Stroke-CareApp: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172082

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrades-González, Ismael, Neiva Rodríguez-Estrabot, Rocío Magdaleno-Moya, and Jesús Molina-Mula. 2025. "Perceptions and Attitudes of Informal Caregivers of Stroke Patients Regarding the Stroke-CareApp: A Phenomenological Study" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172082

APA StyleAndrades-González, I., Rodríguez-Estrabot, N., Magdaleno-Moya, R., & Molina-Mula, J. (2025). Perceptions and Attitudes of Informal Caregivers of Stroke Patients Regarding the Stroke-CareApp: A Phenomenological Study. Healthcare, 13(17), 2082. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172082