Investigating Nutrition and Supportive Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

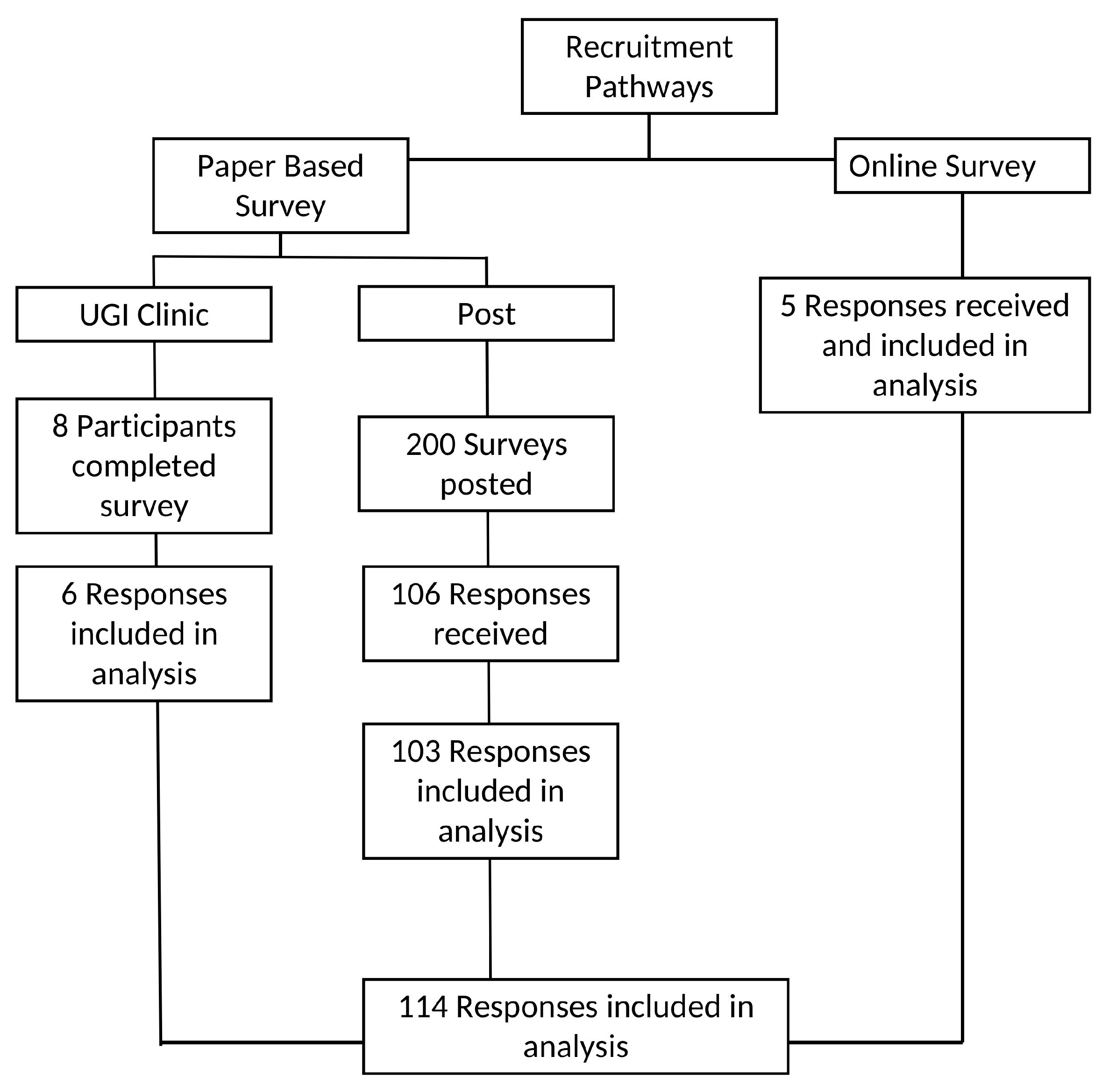

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Scale | Sample Mean (SD) | Reference Values [50] General Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Health Status/QoL | QoL (n = 107) | 66.27 (24.21) | 71.2 (22.4) |

| Functional scales 1 | Physical functioning (n = 111) | 79.50 (20.80) | 89.8 (16.2) |

| Role functioning (n = 112) | 77.67 (28.61) | 84.7 (25.4) | |

| Emotional functioning (n = 111) | 78.3 (26.61) | 76.3 (22.8) | |

| Cognitive functioning (n = 111) | 79.27 (20.25) | 86.1 (20) | |

| Social functioning (n = 111) | 74.62 (26.57) | 87.5 (22.9) | |

| Symptom scales 2 | Fatigue (n = 111) | 31.83 (21.25) | 24.1 (24) |

| Nausea and vomiting (n = 112) | 13.24 (20.88) | 3.7 (11.7) | |

| Pain (n = 111) | 15.76 (22.90) | 20.9 (27.6) | |

| Dyspnea (n = 112) | 19.94 (27.01) | 11.8 (22.8) | |

| Insomnia (n = 111) | 27.92 (31.63) | 21.8 (29.7) | |

| Appetite loss (n = 111) | 22.52 (32.46) | 6.7 (18.3) | |

| Constipation (n = 112) | 14.88 (24.02) | 6.7 (18.4) | |

| Diarrhea (n = 110) | 23.63 (29.03) | 7.0 (18) | |

| Financial difficulties (n = 110) | 17.57 (26.60) | 9.5 (23.3) |

4. Discussion

4.1. Malnutrition

4.2. Nutrition Care and Information Needs

4.3. Gastrointestinal Symptoms

4.4. Quality of Life

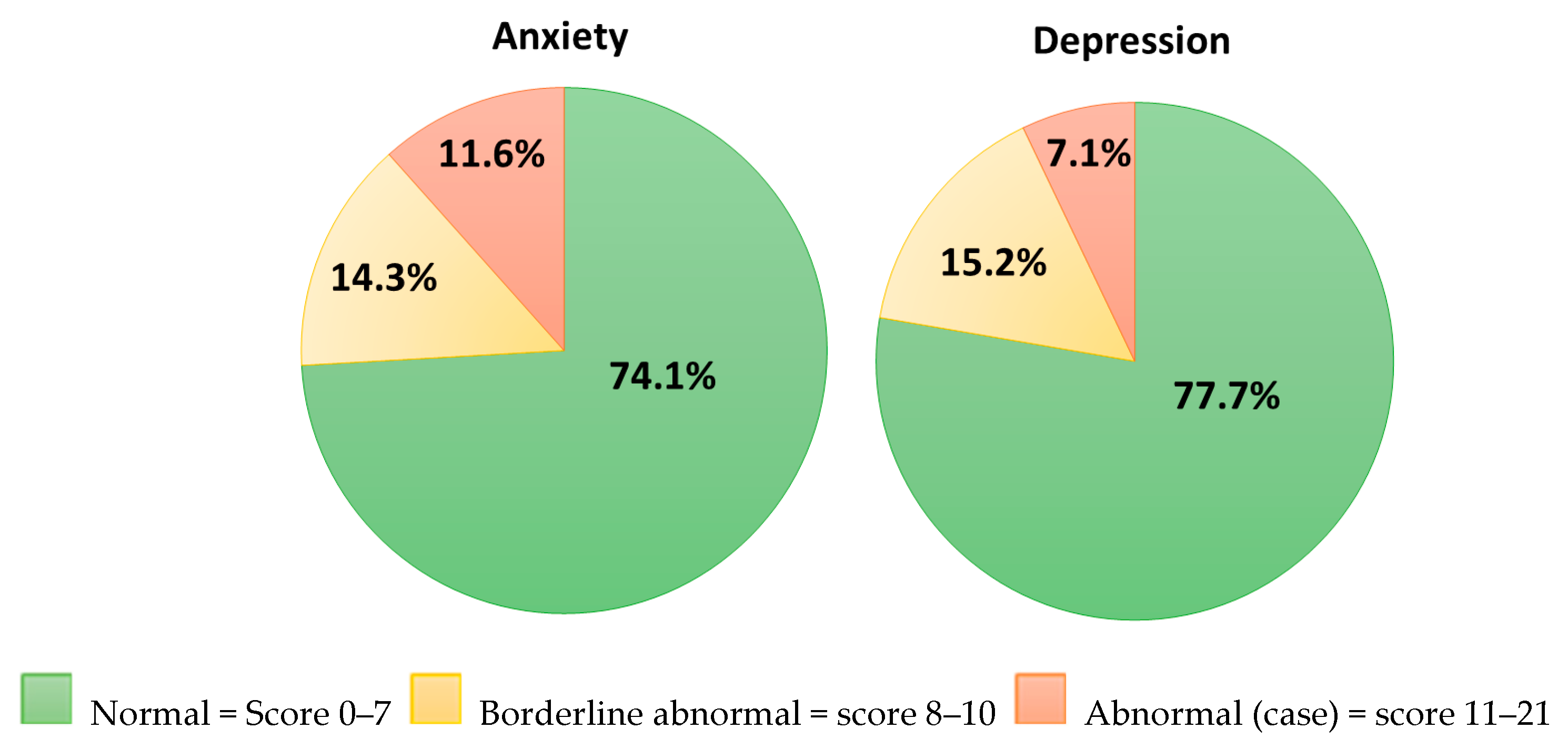

4.5. Psychological Status

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NIS | Nutrition Impact Symptoms |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| UGI | Upper Gastrointestinal |

| MST | Malnutrition Screening Tool |

| EORTC-QLQ-C30 | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| GSRS | Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| MCID | Minimal Clinically Important Difference |

| TCI | Thresholds for clinical importance |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| UWL | Unintentional Weight Loss |

| HRQOL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| PROs | Patient-Reported Outcomes PROs |

References

- Sun, L.; Zhao, K.; Liu, X.; Meng, X. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Esophageal Cancer: A Comprehensive Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Deaths, and DALYs with Forecast Trends Through 2030. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4707419 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Liu, C.-Q.; Ma, Y.-L.; Qin, Q.; Wang, P.-H.; Luo, Y.; Xu, P.-F.; Cui, Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in 2020 and projections to 2030 and 2040. Thorac. Cancer 2023, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thrift, A.P.; Wenker, T.N.; El-Serag, H.B. Global burden of gastric cancer: Epidemiological trends, risk factors, screening and prevention. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.J.; Carbajal, J.; Alfaro, A.L.; Saravia, L.G.; Zanabria, D.; Araujo, J.M.; Quispe, L.; Zevallos, A.; Buleje, J.L.; Cho, C.E.; et al. Characteristics of gastric cancer around the world. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 181, 103841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wang, W.; Fan, M.; Lin, R. The differences in gastric cancer epidemiological data between SEER and GBD: A joinpoint and age-period-cohort analysis. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Registry Ireland. Cancer in Ireland 1994–2021: Annual Statistical Report of the National Cancer Registry; NCRI: Cork, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arends, J.; Baracos, V.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Calder, P.; Deutz, N.; Erickson, N.; Laviano, A.; Lisanti, M.; Lobo, D. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneghan, H.M.; Zaborowski, A.; Fanning, M.; McHugh, A.; Doyle, S.; Moore, J.; Ravi, N.; Reynolds, J.V. Prospective study of malabsorption and malnutrition after esophageal and gastric cancer surgery. Ann. Surg. 2015, 262, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.; Moran, J.; Guinan, E.M.; Reynolds, J.V.; Hussey, J. Physical decline and its implications in the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonowicz, S.; Reddy, S.; Sgromo, B. Gastrointestinal side effects of upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 48–49, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.N. Managing complications I: Leaks, strictures, emptying, reflux, chylothorax. J. Thorac. Dis. 2014, 6 (Suppl. 3), S355–S363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Halliday, V.; Williams, R.N.; Bowrey, D.J. A systematic review of the nutritional consequences of esophagectomy. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Lara, K.; Ugalde-Morales, E.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Green, D. Gastrointestinal symptoms and weight loss in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 894–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharagozlian, S.; Mala, T.; Brekke, H.K.; Kolbjørnsen, L.C.; Ullerud, Å.A.; Johnson, E. Nutritional status, sarcopenia, gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life after gastrectomy for cancer—A cross-sectional pilot study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 37, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikman, A.; Smedfors, G.; Lagergren, P. Emotional distress—a neglected topic among surgically treated oesophageal cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2013, 52, 1783–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergquist, H.; Ruth, M.; Hammerlid, E. Psychiatric morbidity among patients with cancer of the esophagus or the gastro-esophageal junction: A prospective, longitudinal evaluation. Dis. Esophagus 2007, 20, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jang, Y.; Hyung, W. Mediating Effect of Illness Perception on Psychological Distress in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Gastric Cancer: Based on the Common-Sense Model of Self-regulation. Cancer Nurs. 2023, 46, E138–E145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, M.; McCorry, N.K.; Brennan, E.; Donnelly, M.; Murray, L.; Johnston, B.T. Psychological distress among survivors of esophageal cancer: The role of illness cognitions and coping. Dis. Esophagus 2012, 25, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMatteo, M.R.; Lepper, H.S.; Croghan, T.W. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: Meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 2101–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housman, B.; Flores, R.; Lee, D.S. Narrative review of anxiety and depression in patients with esophageal cancer: Underappreciated and undertreated. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 3160–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkura, Y.; Ichikura, K.; Shindoh, J.; Ueno, M.; Udagawa, H.; Matsushima, E. Relationship between psychological distress and health-related quality of life at each point of the treatment of esophageal cancer. Esophagus 2020, 17, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderon, C.; Carmona-Bayonas, A.; Beato, C.; Ghanem, I.; Hernandez, R.; Majem, M.; Rosa Diaz, A.; Higuera, O.; Mut Lloret, M.; Jimenez-Fonseca, P. Risk of malnutrition and emotional distress as factors affecting health-related quality of life in patients with resected cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 21, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.; Drummond, F.; O’Donovan, B.; Donnelly, C. The Unmet Needs of Cancer Survivors in Ireland: A Scoping Review 2019; National Cancer Registry Ireland: Cork, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, A.; Tokell, M.; Ishak, Y.; Love, J.; Klammer, M.; Koh, M. Mental health needs in cancer—a call for change. Future Healthc. J. 2023, 10, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefford, M.; Howell, D.; Li, Q.; Lisy, K.; Maher, J.; Alfano, C.M.; Rynderman, M.; Emery, J. Improved models of care for cancer survivors. Lancet 2022, 399, 1551–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haahr, M. What’s This Fuss About True Randomness. 2009. Available online: https://www.random.org (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Ferguson, M.; Capra, S.; Bauer, J.; Banks, M. Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients. Nutrition 1999, 15, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenring, E.; Cross, G.; Daniels, L.; Kellett, E.; Koczwara, B. Validity of the malnutrition screening tool as an effective predictor of nutritional risk in oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 2006, 14, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, M.; Kurmann, S.; Stanga, Z. Nutritional screening tools in daily clinical practice: The focus on cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.S.; Rice, N.; Kingston, E.; Kelly, A.; Reynolds, J.V.; Feighan, J.; Power, D.G.; Ryan, A.M. A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 41, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L.; McGough, A.M.; Du, M.; Chang, W.; Chomitz, V.; Allen, J.D.; Attai, D.J.; Gualtieri, L.; Zhang, F.F. Self-Reported Changes and Perceived Barriers to Healthy Eating and Physical Activity among Global Breast Cancer Survivors: Results from an Exploratory Online Novel Survey. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 233–241.e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschke, J.; Kruk, U.; Kastrati, K.; Kleeberg, J.; Buchholz, D.; Erickson, N.; Huebner, J. Nutritional care of cancer patients: A survey on patients’ needs and medical care in reality. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 22, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeliger, J.; Dewar, S.; Kiss, N.; Drosdowsky, A.; Stewart, J. Patient and carer experiences of nutrition in cancer care: A mixed-methods study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5475–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaronson, N.K.; Ahmedzai, S.; Bergman, B.; Bullinger, M.; Cull, A.; Duez, N.J.; Filiberti, A.; Flechtner, H.; Fleishman, S.B.; de Haes, J.C. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1993, 85, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.T. The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual. Life Res. 1996, 5, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osoba, D.; Rodrigues, G.; Myles, J.; Zee, B.; Pater, J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesinger, J.M.; Loth, F.L.C.; Aaronson, N.K.; Arraras, J.I.; Caocci, G.; Efficace, F.; Groenvold, M.; van Leeuwen, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Ramage, J.; et al. Thresholds for clinical importance were established to improve interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 in clinical practice and research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedlund, J.; Sjödin, I.; Dotevall, G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1988, 33, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimenäs, E.; Glise, H.; Hallerbäck, B.; Hernqvist, H.; Svedlund, J.; Wiklund, I. Quality of life in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms: An improved evaluation of treatment regimens? Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1993, 28, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimenäs, E.; Glise, H.; Hallerbäck, B.; Hernqvist, H.; Svedlund, J.; Wiklund, I. Well-being and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients referred to endoscopy owing to suspected duodenal ulcer. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1995, 30, 1046–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulich, K.R.; Madisch, A.; Pacini, F.; Piqué, J.M.; Regula, J.; Van Rensburg, C.J.; Újszászy, L.; Carlsson, J.; Halling, K.; Wiklund, I.K. Reliability and validity of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in dyspepsia: A six-country study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimenäs, E.; Carlsson, G.; Glise, H.; Israelsson, B.; Wiklund, I. Relevance of norm values as part of the documentation of quality of life instruments for use in upper gastrointestinal disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1996, 221, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, M.A.; Muzzatti, B.; Bidoli, E.; Flaiban, C.; Bomben, F.; Piccinin, M.; Gipponi, K.M.; Mariutti, G.; Busato, S.; Mella, S. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) accuracy in cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3921–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Hays, R.D.; Shreiner, A.B.; Melmed, G.Y.; Chang, L.; Khanna, P.P.; Bolus, R.; Whitman, C.; Paz, S.H.; Hays, T.; et al. Responsiveness to Change and Minimally Important Differences of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Gastrointestinal Symptoms Scales. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, S.; Murphy, C.F.; Fanning, M.; Reynolds, J.V.; Doyle, S.L.; Donohoe, C.L. The impact of Nutrition and Gastrointestinal Symptoms on Health-related Quality of Life in Survivorship after Oesophageal Cancer Surgery. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2022, 41, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, S.; Liegl, G.; Petersen, M.A.; Aaronson, N.K.; Costantini, A.; Fayers, P.M.; Groenvold, M.; Holzner, B.; Johnson, C.D.; Kemmler, G.; et al. General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the Unites States. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 107, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, N.W.; Fayers, P.; Aaronson, N.K.; Bottomley, A.; de Graeff, A.; Groenvold, M.; Gundy, C.; Koller, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Sprangers, M.A. EORTC QLQ-C30 Reference Values Manual; EORTC Quality of Life Group: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, J.R.; Henry, J.D.; Crombie, C.; Taylor, E.P. Normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 40, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; You, J.; Wang, K.; Cao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, R.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, L.; et al. Effect of whole-course nutrition management on patients with esophageal cancer undergoing concurrent chemoradiotherapy: A randomized control trial. Nutrition 2020, 69, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébuterne, X.; Lemarié, E.; Michallet, M.; de Montreuil, C.B.; Schneider, S.M.; Goldwasser, F. Prevalence of Malnutrition and Current Use of Nutrition Support in Patients With Cancer. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2014, 38, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, E.S.; Rice, N. National Malnutrition Screening Survey Republic of Ireland 2023: A Report by the Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition & Metabolism (IrSPEN); Irish Society for Clinical Nutrition & Metabolism (IrSPEN): Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Garth, A.K.; Newsome, C.M.; Simmance, N.; Crowe, T.C. Nutritional status, nutrition practices and post-operative complications in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. J. Human. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Xu, H.; Li, W.; Guo, Z.; Lin, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hu, W.; Ba, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Nutritional assessment and risk factors associated to malnutrition in patients with esophageal cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2021, 45, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T.; Mastnak, D.M.; Palamar, N.; Kozjek, N.R. Nutritional Therapy for Patients with Esophageal Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.E.; O’Neill, L.; Doyle, S.L.; Guinan, E.M.; O’Sullivan, J.; Reynolds, J.V.; Hussey, J. Nutrient Intakes and Gastrointestinal Symptoms Among Esophagogastric Cancer Survivors up to 5 Years Post-Surgery. Nutr. Cancer 2024, 76, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.W.; Bae, J.M.; Kim, E.M.; An, J.Y.; Choi, M.G.; Lee, J.H.; Sohn, T.S. Long-term effect of simplified dietary education on the nutritional status of patients after a gastrectomy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, E.Y.N.; Zaleta, A.K.; McManus, S.; Buzaglo, J.S.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Hamilton, K.; Stein, K. Unintentional weight loss, its associated burden, and perceived weight status in people with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, H.; Deng, G.; Shi, X.; Liu, Z.; Lin, A.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Luo, P. Body mass index, weight change, and cancer prognosis: A meta-analysis and systematic review of 73 cohort studies. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmström, M.; Ivarsson, B.; Johansson, J.; Klefsgård, R. Long-term experiences after oesophagectomy/gastrectomy for cancer—A focus group study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Wooten, L.A.; Malloy, M. Nutritional considerations after gastrectomy and esophagectomy for malignancy. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2011, 12, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.R.d.M.; de Oliveira, M.G.O.A.; Souza, A.S.R.; Figueroa, J.N.; Santos, C.S. Factors associated with malnutrition in hospitalized cancer patients: A croos-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthman, O.A.; Jadidi, E.; Moradi, T. Socioeconomic position and incidence of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-M.; Wang, T.-J.; Huang, C.-S.; Liang, S.-Y.; Yu, C.-H.; Lin, T.-R.; Wu, K.-F. Nutritional Status and Related Factors in Patients with Gastric Cancer after Gastrectomy: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, F.d.C.P.; Silva, T.A.; Generoso, S.d.V.; Correia, M.I.T.D. Malnutrition is associated with poor health-related quality of life in surgical patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Nutrition 2020, 75–76, 110769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.C.; Duncan, G.J.; McDonough, P.; Williams, D.R. Optimal indicators of socioeconomic status for health research. Am. J. Public. Health 2002, 92, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeken, R.J.; Williams, K.; Wardle, J.; Croker, H. “What about diet?” A qualitative study of cancer survivors’ views on diet and cancer and their sources of information. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, N.; Douglas, P.; Keaver, L. Nutrition Practices among Adult Cancer Survivors Living on the Island of Ireland: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Molfino, A.; Scala, F.; De Lorenzo, F.; Christoforidi, K.; Manneh-Vangramberen, I. European survey of 907 people with cancer about the importance of nutrition. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, v513–v514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, F.; Hussey, J.; Doyle, S.L. “One Size Doesn’t Fit All”: Nutrition Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors—A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute. Submission to the National Cancer Strategy 2016–2025; The Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute: Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.T.; Law, L.; De Guzman, K.R.; Hickman, I.J.; Mayr, H.L.; Campbell, K.L.; Snoswell, C.L.; Erku, D. Cost-effectiveness of telehealth-delivered nutrition interventions: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2023, 81, 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llaha, F.; Ribalta, A.; Arribas, L.; Bellver, M.; Roura, E.; Guillén-Rey, N.; Megias-Rangil, I.; Alegret-Basora, C.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Zamora-Ros, R. A Review of Web-Based Nutrition Information in Spanish for Cancer Patients and Survivors. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.L. Social Media Use in Cancer Care. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 34, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boshier, P.R.; Klevebro, F.; Savva, K.V.; Waller, A.; Hage, L.; Hanna, G.B.; Low, D.E. Assessment of Health Related Quality of Life and Digestive Symptoms in Long-term, Disease Free Survivors After Esophagectomy. Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, e140–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, U.; Bosaeus, I.; Svedlund, J.; Bergbom, I. Patients’ subjective symptoms, quality of life and intake of food during the recovery period 3 and 12 months after upper gastrointestinal surgery. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2007, 16, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, N.; Schinkoethe, T.; Eckhardt, C.; Storck, L.; Joos, A.; Liu, L.; Ballmer, P.E.; Mumm, F.; Fey, T.; Heinemann, V. Patient-reported outcome measures obtained via E-Health tools ease the assessment burden and encourage patient participation in cancer care (PaCC Study). Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 7715–7724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, B.-B.E.; Chen, R.C. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivorship. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.; Macefield, R.; Elbers, R.; Sitnikova, K.; Korfage, I.; Smets, E.; Henselmans, I.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.; de Haes, J.; Blazeby, J.M. Meta-analysis shows clinically relevant and long-lasting deterioration in health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1097–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, K.; Hughes, R.; McNair, A.; Alderson, D.; Barham, P.; Blazeby, J. Health-related quality of life and survival in the 2years after surgery for gastric cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2010, 36, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallance, P.C.; Mack, L.; Bouchard-Fortier, A.; Jost, E. Quality of Life Following the Surgical Management of Gastric Cancer Using Patient-Reported Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandl, A.; Cheng, Z.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Health-related quality of life 15 years after oesophageal cancer surgery: A prospective nationwide cohort study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2023, 17, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandl, A.; Lagergren, J.; Johar, A.; Lagergren, P. Health-related quality of life 10 years after oesophageal cancer surgery. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 69, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noordman, B.J.; Verdam, M.G.E.; Lagarde, S.M.; Shapiro, J.; Hulshof, M.C.C.M.; van Berge Henegouwen, M.I.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; Nieuwenhuijzen, G.A.P.; Bonenkamp, J.J.; Cuesta, M.A.; et al. Impact of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of esophageal or junctional cancer: Results from the randomized CROSS trial. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Q.C. Health-related quality of life and survival among 10-year survivors of esophageal cancer surgery: Gastric tube reconstruction versus whole stomach reconstruction. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, 3284–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenkman, H.J.F.; Tegels, J.J.W.; Ruurda, J.P.; Luyer, M.D.P.; Kouwenhoven, E.A.; Draaisma, W.A.; van der Peet, D.L.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; Stoot, J.H.M.B.; van Hillegersberg, R.; et al. Factors influencing health-related quality of life after gastrectomy for cancer. Gastric Cancer 2018, 21, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolazco, J.I.; Chang, S.L. The role of health-related quality of life in improving cancer outcomes. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2023, 9, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, F.; Lethrosne, C.; Pourel, N.; Molinier, O.; Pointreau, Y.; Domont, J.; Bourgeois, H.; Senellart, H.; Trémolières, P.; Lizée, T. Randomized trial comparing a web-mediated follow-up with routine surveillance in lung cancer patients. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Dueck, A.C.; Scher, H.I.; Kris, M.G.; Hudis, C.; Schrag, D. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 2017, 318, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Kris, M.G.; Scher, H.I.; Hudis, C.A.; Sabbatini, P.; Rogak, L.; Bennett, A.V.; Dueck, A.C.; Atkinson, T.M. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schandl, A.; Johar, A.; Anandavadivelan, P.; Vikström, K.; Mälberg, K.; Lagergren, P. Patient-reported outcomes 1 year after oesophageal cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, K.T.; McConnell, K.M.; Currier, M.B.; Baser, R.E.; MacLeod, J.; Walker, D.; Casaw, C.; Wong, G.; Piulson, L.; Popkin, K.; et al. Telehealth-Based Music Therapy Versus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety in Cancer Survivors: Rationale and Protocol for a Comparative Effectiveness Trial. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e46281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghowinam, M.A.; Albokhari, A.A.; Badheeb, A.M.; Lamlom, M.; Alwadai, M.; Hamza, A.; Aladalah, A. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Among Patients with Cancer in Najran, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e54349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Knifton, L.; Robb, K.A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Smith, D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakhsh, N.; Moudi, S.; Abbasian, S.; Khafri, S. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 5, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Hellstadius, Y.; Lagergren, J.; Zylstra, J.; Gossage, J.; Davies, A.; Hultman, C.M.; Lagergren, P.; Wikman, A. A longitudinal assessment of psychological distress after oesophageal cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, Z.; Gossage, J.; Evans, O.; Cuffe, R.; On Behalf of the Guy’s St Thomas’ Oesophago-Gastric Research Group. Unmet needs in survivorship: Increased anxiety post oesophago-gastric cancer surgery. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108046. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, R.S.; Ye, J.; Baltrus, P.; Fry-Johnson, Y.; Daniels, E.; Rust, G. Racial/ethnic disparities, social support, and depression: Examining a social determinant of mental health. Ethn. Dis. 2012, 22, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- General, O.o.t.S.; Services, C.f.M.H. Culture counts: The influence of culture and society on mental health. In Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tedstone Doherty, D.; Moran, R.; Kartalova-O’Doherty, Y. Psychological Distress, Mental Health Problems and Use of Health Services in Ireland; HRB Research Series 5; Health Research Board: Dublin, Ireland, 2008.

- McHugh Power, J.; Tang, J.; Kenny, R.A.; Lawlor, B.A.; Kee, F. Mediating the relationship between loneliness and cognitive function: The role of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemay, K.R.; Tulloch, H.E.; Pipe, A.L.; Reed, J.L. Establishing the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2019, 39, E6–E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Gee, H.; O’Hanlon, A.; Barker, M.; Hickey, A.; Garavan, R.; Conroy, R.; Layte, R.; Shelley, E.; Horgan, F.; Crawford, V. One Island–Two Systems: A Comparison of Health Status and Health and Social Service Use by Community-Dwelling Older People in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland; The Institute of Public Health in Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harrold, E.C.; Idris, A.F.; Keegan, N.M.; Corrigan, L.; Teo, M.Y.; O’Donnell, M.; Lim, S.T.; Duff, E.; O’Donnell, D.M.; Kennedy, M.J.; et al. Prevalence of Insomnia in an Oncology Patient Population: An Irish Tertiary Referral Center Experience. J. Natl. Compr. Canc Netw. 2020, 18, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyster, F.S.; Hughes, J.W.; Gunstad, J. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Are Associated with Reduced Dietary Adherence in Heart Failure Patients Treated with an Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2009, 24, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, A.J. Digital Inequality During a Pandemic: Quantitative Study of Differences in COVID-19-Related Internet Uses and Outcomes Among the General Population. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, S. Bridging the Age-based Digital Divide: An Intergenerational Exchange during the First COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown Period in Ireland. J. Intergener. Relatsh. 2022, 20, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziuba, S.; Cierniak-Emerych, A.; Michalski, G.; Poulová, P.; Mohelská, H.; Klímová, B. The use of the internet by older adults in Poland. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) mean ± SD, range, (n = 110) | 70.36 ± 9.19, 41–88 | - |

| Gender, (n = 114) | Female | 42 (36.8) |

| Male | 72 (63.1) | |

| Living arrangement, (n = 114) | Living with others | 93 (81.6) |

| Living alone | 21 (18.4) | |

| Employment status, (n = 114) | Employed | 24 (21) |

| Not employed | 90 (78.9) | |

| Ethnicity, (n = 114) | Irish | 107 (93.8) |

| Other White backgrounds | 7 (6.1) | |

| Health insurance, (n = 114) | Public | 47 (41.2) |

| Private | 61 (53.5) | |

| None | 6 (5.2) | |

| Education, (n = 112) | University degree | 39 (34.8) |

| No university degree | 73 (65.17) | |

| Cancer diagnosis | Esophageal cancer | 86 (75.4) |

| Gastric cancer | 28 (24.5) | |

| Time from diagnosis (months) mean ± SD, (n = 108) | 44.76 ± 34.18 | - |

| Range: 2–270 | ||

| Cancer treatment, (n = 114) | Surgery only | 43 (37.7) |

| Chemotherapy only | 1 (0.87) | |

| Surgery + chemotherapy/radiotherapy/immunotherapy | 70 (61.4) | |

| No longer receiving treatment | 48 (42.1) | |

| On a break from cancer treatment | 4 (3.5) | |

| Nutritional Status | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| MST score (mean ± SD) | 1.11 ± 1.51 | - |

| Risk of malnutrition | Low | 79 (69.29) |

| Medium | 21 (18.42) | |

| High | 14 (12.28) | |

| Ongoing nutrition impact symptoms | Yes | 42 (36.84) |

| No | 72 (63.15) | |

| GSRS Domains Score | Sample | Reference Value, General Population [43] | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean Score (SD) | CI | Mean Score | ||

| Abdominal pain syndrome (score range 1–7) | 109 | 1.85 (1.01) | 1.65, 2.04 | 1.56 | 0.004 |

| Reflux syndrome (score range 1–7) | 108 | 2.05 (1.41) | 1.78, 2.32 | 1.39 | <0.001 |

| Diarrhea syndrome (score range 1–7) | 113 | 2.40 (1.59) | 2.11, 2.70 | 1.38 | <0.001 |

| Indigestion syndrome (score range 1–7) | 111 | 2.15 (1.24) | 1.91, 2.38 | 1.78 | 0.002 |

| Constipation syndrome (score range 1–7) | 113 | 1.93 (1.23) | 1.70, 2.16 | 1.55 | 0.001 |

| Total score | 108 | 2.06 (1.02) | 1.86, 2.25 | 1.53 | <0.001 |

| Sample Mean (SD) (n = 112) | Normative Value (General Population) Mean (SD) [51] | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety scale | 5.26 (4.48) | 6.14 (3.76) |

| Depression scale | 4.72 (3.81) | 3.68 (3.07) |

| Total score | 9.98 (7.70) | 9.82 (5.98) |

| Nutrition Care Needs | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Concern about weight loss (n = 110) | |

| Not concerned at all | 51 (46.3) |

| A bit concerned | 31 (28.18) |

| Moderately concerned | 18 (16.36) |

| Severely concerned | 10 (9.09) |

| Sought advice from a dietitian (n = 109) | |

| Yes | 63 (57.7) |

| No | 46 (42.2) |

| Would benefit from further dietitian contact (n = 111) | |

| Yes | 58 (52.25) |

| No | 53 (47.74) |

| Expression of interest in nutrition information (n = 111) | |

| Interested | 64 (57.65) |

| Not interested | 47 (42.34) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadeghi, F.; Hussey, J.; Doyle, S.L. Investigating Nutrition and Supportive Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162057

Sadeghi F, Hussey J, Doyle SL. Investigating Nutrition and Supportive Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162057

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadeghi, Fatemeh, Juliette Hussey, and Suzanne L. Doyle. 2025. "Investigating Nutrition and Supportive Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162057

APA StyleSadeghi, F., Hussey, J., & Doyle, S. L. (2025). Investigating Nutrition and Supportive Care Needs in Esophageal and Gastric Cancer Survivors: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Healthcare, 13(16), 2057. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162057