Trends in Pediatric Malpractice Claims at a Tertiary Children’s Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Unique identification code of the claim: implemented to ensure traceability within the database.

- -

- Age and sex of the injured patient.

- -

- Event date.

- -

- Method of admission to the hospital: ordinary/urgent/emergency. In cases of department transfers, the severity assigned to being admitted to the department in which the incident that prompted the compensation request occurred was noted. Clinical improvement or deterioration during hospitalization was deemed irrelevant to the initial access method.

- -

- Type of setting to which the issue raised by the applicant pertains. The categories identified included the emergency department, hospitalization (which encompasses short-term hospitalizations, such as day and week hospitals), outpatient services, consultation, teleconsultation, and laboratory services.

- -

- Specialist area associated with the incident that led to the compensation request.

- -

- Nature of the issue for which compensation is sought.

- -

- Surgical errors, which concerned invasive procedures, including endoscopic treatments and outpatient surgical procedures;

- -

- Therapeutic errors, which involved the administration of drugs or other non-invasive forms of therapy;

- -

- Diagnostic errors, which pertained to the recognition of a pathological condition, whether through laboratory or instrumental examinations, or by direct patient observation.

- -

- Date of formulation of the first compensation request;

- -

- Date of closure of the litigation;

- -

- Type of damage referred to in the complaint;

- -

- Technical consultancy on behalf of the party;

- -

- Involvement of third parties and agreements with other hospitals;

- -

- Medico-legal evaluation of the damage;

- -

- Path of the claim: for each compensation claim, both the type and number of judicial and extrajudicial steps undertaken were considered, including the sequence in which these steps occurred;

- -

- Claim outcome: the compensation claims were categorized according to the final outcome established either in extrajudicial or judicial proceedings:

- Accepted if, at the conclusion of the litigation process, any sum of compensation was granted (blue in the columns);

- Rejected if, at the conclusion of the litigation process, no compensation was granted (red in the columns);

- In progress if the case is actively developing, irrespective of the stage attained and any significant inclination towards acceptance or rejection (purple in the columns);

- Without a follow-up if, despite repeated reminders, the claimant failed to respond to Meyer’s requests for documentation, for undergoing a medicolegal examination, or for providing clarification. This lack of cooperation prevents Meyer from proceeding further with the processing of the case. The time required for the CMC to classify a case as closed without further action is generally 18 months (green in the columns).

- -

- Official technical consultancy (OTC). We observed whether one or more OTCs were conducted for each request, at what stage in the process they were organized, and whether they provided evidence for the rejection or acceptance of the compensation request.

- -

- Definition of the amount of compensation.

- -

- Recurrence of rare disease. All subjects were considered to have a rare disease if there was documentary evidence of them being affected by pathological conditions, or variants thereof, whose recurrence in the literature is reliably attested to be less than or equal to 1 in 2000. Subjects were classified as affected even if the rare disease in question was not related to the issue that led to the compensation claim.

- -

- ICPS results. In instances where Meyer Children’s Hospital was acknowledged as liable, the damage resulting from such liability has been categorized according to the International Classification of Patient Safety. The World Health Organization’s International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) identified incident characteristics, patient outcome (none; mild, moderate; severe; death), and their contributing factors in cases involving complications of medical or surgical care [25].

- -

- None—Patient outcome is not symptomatic, no symptoms are detected, and no treatment is required.

- -

- Mild—Patient outcome is symptomatic, symptoms are mild, the loss of function or harm is minimal or intermediate but short term, and no or minimal intervention (e.g., extra observation, investigation, review or minor treatment) is required.

- -

- Moderate—Patient outcome is symptomatic, intervention is required (e g., additional operative procedure; additional therapeutic treatment), an increased length of stay is required, or permanent or long-term harm or loss of function is caused.

- -

- Severe—Patient outcome is symptomatic, life-saving intervention or major surgical/medical intervention is required, and a shortened life expectancy, major permanent or long-term harm, or loss of function is caused.

- -

- Death—When balancing the probabilities, death was caused or hastened in the short term by the incident.

3. Results

3.1. Numbers of Claims per Year

3.2. Outcome of Claims

3.3. Age and Sex of Patients

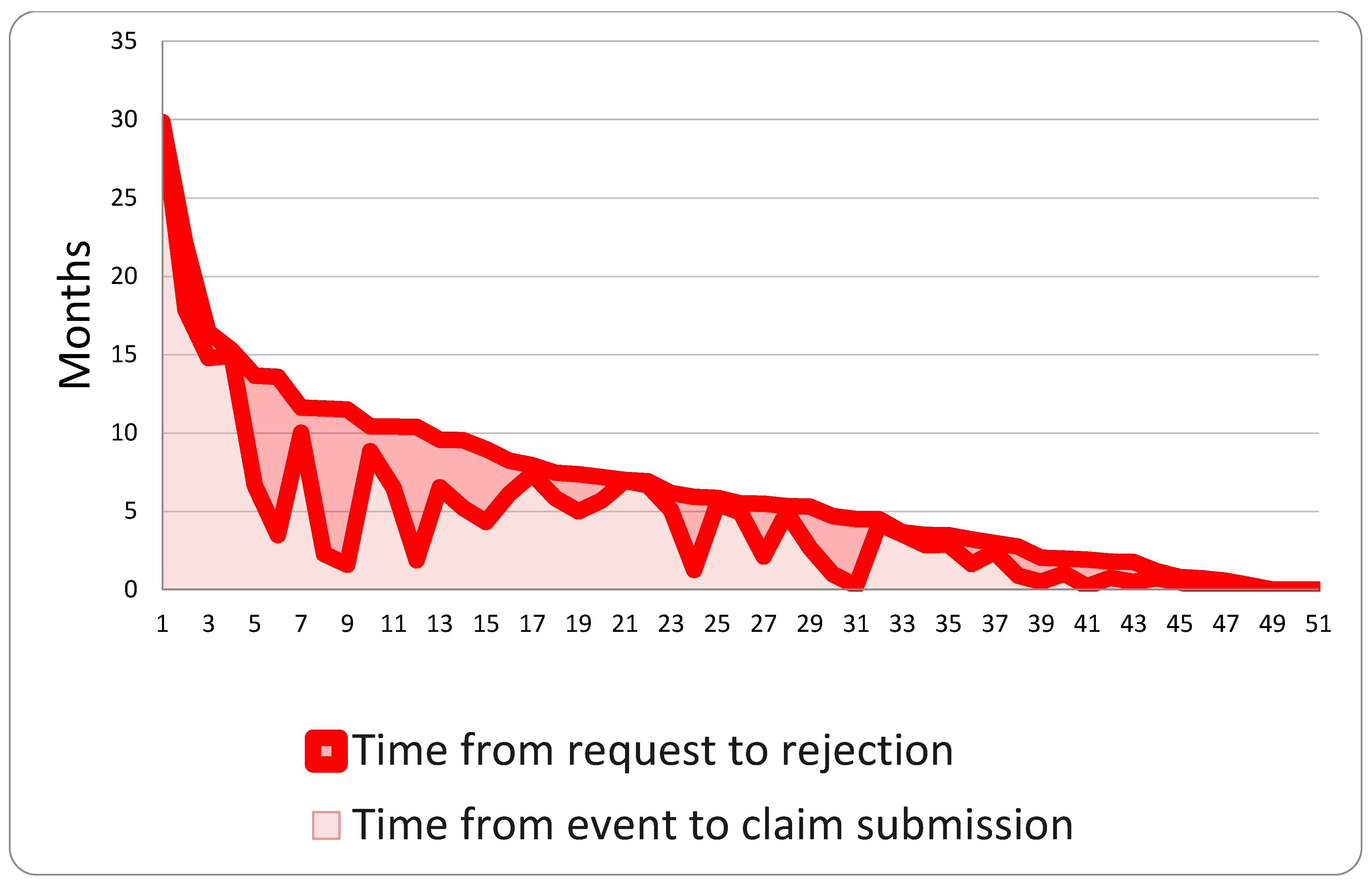

3.4. Claim Management Process

3.5. Trend of the Claim with ADR and Judicial

3.6. Clinical Setting and Type of Recovery

3.7. Type of Error

- -

- Forty-two cases were concluded with compensation for damages.

- -

- Six are still pending.

- -

- Seven were unsuccessful.

- -

- One was ultimately dismissed, despite a potential finding of liability on the part of Meyer Children’s Hospital, due to the significant difference between the amount recoverable and the compensation requested.

3.8. Type of Damage Referred to in the Complaint

3.9. Definition of the Economic Amount of Compensation

3.10. ICPS Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ehara, A. Lawsuits associated with medical malpractice in Japan: Rate of lawsuits was very low in pediatrics, although many children visit emergency rooms. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 1792–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, J.D.; Spector, R.A. Malpractice claims analysis yields widely applicable principles. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2003, 24, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leape, L.L.; Brennan, T.A.; Laird, N.; Lawthers, A.G.; Localio, A.R.; Barnes, B.A.; Hebert, L.; Newhouse, J.P.; Weiler, P.C.; Hiatt, H. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, D.; Thomas, E.; Holl, J.; Altman, S.; Brennan, T. Adverse events and preventable adverse events in children. Pediatrics 2005, 115, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, A.E.; Buddenbaum, J.L. Malpractice claims involving pediatricians: Epidemiology and etiology. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, G.; Keene, J.; Raine, J. An analysis of successful litigation claims in childhood fatalities in England. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2012, 171, 1657–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyengar, A.; Morris, T.; Bagshaw, K.; Aladangady, N. Systematic review of medical literature for medicolegal claims and complaints involving neonates. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nunno, N.; Patanè, F.G.; Mico, F.; Asmundo, A.; Pomara, C. The Role of a Good Quality Autopsy in Pediatric Malpractice Claim: A Case Report of an Unexpected Death in an Undiagnosed Thymoma. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, M.H.; Ergönen, T.A.; Can, I.O. Medical malpractice claims involving children. Forensic Sci. Int. 2009, 191, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treglia, M.; Pallocci, M.; Passalacqua, P.; Giammatteo, J.; De Luca, L.; Mauriello, S.; Cisterna, A.M.; Marsella, A. Medical Liability: Review of a Whole Year of Judgments of the Civil Court of Rome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebala, G.D.; Slack, Z.; Fantini, V.; Masato, S.; Parla, M.; Cirocchi, R.; Di Saverio, S. Professional responsibility between guidelines and customary practice. A conflict of interest? Med. Hypotheses 2021, 158, 110737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najaf-Zadeh, A.; Dubos, F.; Aurel, M.; Martinot, A. Epidemiology of malpractice lawsuits in paediatrics. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, M.H.; Cekin, N.; Can, I.O.; Hilal, A. Malpractice and system of expertise in anaesthetic procedures in Turkey. Forensic Sci. Int. 2005, 153, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najaf-Zadeh, A.; Dubos, F.; Pruvost, I.; Bons-Letouzey, C.; Amalberti, R.; Martinot, A. Epidemiology and aetiology of paediatric malpractice claims in France. Arch. Dis. Child. 2011, 96, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanos, V.; Tagliabue, P.; Greco, L.; Agostiniani, R.; Carbone, M.T.; D’Agostino, P.; Correra, A. Neonatal malpractice claims in Italy: How big is the problem and which are the causes? J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traina, F. Medical malpractice: The experience in Italy. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 467, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte-Real, A.; Caetano, C.; Alves, S.; Pereira, A.D.; Rocha, S.; Vieira, D.N. Patient Safety in Dental Practice: Lessons to Learn About the Risks and Limits of Professional Liability. Int. Dent. J. 2021, 71, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh S.p.A. Andamento e Costo del Contenzioso a Livello Nazionale—Iv Edition Medmal Claims Analysis; Marsh S.p.A: Milan, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tuscany Region Council. Administrative System of Litigation. Available online: https://www.regione.toscana.it/-/sistema-assicurativo-e-amministrativo-del-contenzio-1 (accessed on 29 April 2014).

- Direttiva dell’Unione Europea 2011/24/UE del 9 Marzo 2011. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/24/oj/eng (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Decreto Legislativo n. 38 del 4 Marzo 2014. Available online: https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:decreto.legislativo:2014-03-04;38 (accessed on 29 April 2014).

- Joint Commission Accreditation of Meyer Children’s Hospital. Available online: https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/who-we-are/accredited-organizations/?c=Italy#sort=%40aoname%20ascending&f:@aocountry=[Italy] (accessed on 29 April 2014).

- Delibera della, A.O.U. Meyer n. 122 del 04.03.2020.

- Autorization to Conduct the Study n 5142/2024 17.05.2024.

- Runciman, W.; Hibbert, P.; Thomson, R.; Der Schaaf, T.V.; Sherman, H.; Lewalle, P. Towards an International Classification for Patient Safety: Key concepts and terms. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2009, 21, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro Regionale Gestione Rischio Clinico e Sicurezza del Paziente. Report di Relazione Attività del 2023; Centro Regionale Gestione Rischio Clinico e Sicurezza del Paziente: Toscana, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Piano Annuale per la Gestione del Rischio Sanitario (PARS); Report del 24 Febbraio; Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù: Roma, Italy, 2023.

- Marsh S.p.A. Report MedMal. Studio Sull’Andamento del Rischio da Medical Malpractice Nella Sanità Italiana, 14th ed.; Marsh S.p.A.: Milan, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, N.; Posner, K.L.; Cheney, F.W.; Caplan, R.A.; Lee, L.A.; Domino, K.B. An update on pediatric anesthesia liability: A closed claims analysis. Anesth. Analg. 2007, 104, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galey, S.A.; Margalit, A.; Ain, M.C.; Brooks, J.T. Medical Malpractice in Pediatric Orthopaedics: A Systematic Review of US Case Law. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, e482–e486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beez, T.; Steiger, H.J.; Weber, B.; Ahmadi, S.A. Pediatric neurosurgery malpractice claims in Germany. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2019, 35, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.A.; Dwyer, K.; Yu-Moe, W.; Taylor, G.A. Pediatric radiology malpractice claims—Characteristics and comparison to adult radiology claims. Pediatr. Radiol. 2017, 47, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, L.E.; Navaratnam, A.V.; Magowan, D.S.; Machin, J.T.; Briggs, T.W.R.; Hall, A.C. Litigation in pediatric otorhinolaryngology: Lessons in improving patient care. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 162, 111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullins, V.F.; Rouch, J.D.; Lee, S.L. Malpractice in Cases of Pediatric Appendicitis. Clin. Pediatr. 2017, 56, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, M.B.; Jolliff, H. High-Risk Medicolegal Conditions in Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Emerg. Med. Clin. North. Am. 2021, 39, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Russa, R.; Viola, R.V.; D’Errico, S.; Aromatario, M.; Maiese, A.; Anibaldi, P.; Napoli, C.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Analysis of Inadequacies in Hospital Care through Medical Liability Litigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denton, R.; Frogley, C.; Jackson, S.; John, M.; Querstret, D. The assessment of developmental trauma in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 235–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, T.; Almiro, P.A.; Coelho, J.; Caetano, C.; Figueiredo, J.P.; Real, A.C. Orofacial trauma injuries and disability assessment in adolescents: A Portuguese study. Dent. Traumatol. 2022, 38, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norelli, G.A.; De Luca, F.; Focardi, M.; Giardiello, R.; Pinchi, V. The Claims Management Committees trial: Experience of an Italian hospital of the National Health System. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2015, 29, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadom, N. Engaging patients and families in pediatric radiology. Pediatr. Radiol. 2020, 50, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Pré, P.; Brierley, J. Challenges in managing parental expectations in paediatric care. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 183, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopetti, M.; Santurro, A.; Gatto, V.; Padovano, M.; Manetti, F.; D’Errico, S.; Fineschi, V. Information, Sharing, and Self-Determination: Understanding the Current Challenges for the Improvement of Pediatric Care Pathways. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frati, P.; La Russa, R.; Duse, M. Editorial: Pediatric Specificities of Medical Liability: Improvement Measures in Pediatric Settings. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 667020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronconi, L.P.; Basile, G.; Mikus, E.; Prevot, L.B.; Savini, C.; Russo, G.V.L.; Sangiorgi, D.; Bolcato, V. Infective endocarditis and litigation for compensation on healthcare-associated infections: An Italian sample analysis. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2025, 113, 102861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualniera, P.; Mondello, C.; Scurria, S.; Oliva, A.; Grassi, S.; Pizzicannella, J.; Alibrandi, A.; Sapienza, D.; Asmundo, A. Experience of an Italian Hospital Claims Management Committee: A tool for extrajudicial litigations resolution. Leg. Med. 2020, 42, 101657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, S.; Grazzini, M.; Guerini, M.; Bertana, G.; Pompeo, L.; Paolini, D.; Niccolini, F.; Focardi, M.; Pinchi, V. Medico-legal management of healthcare-associated infections: A cost-effectiveness analysis in an Italian tertiary hospital. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1430625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Unique identification code of the claim | Implemented to ensure traceability within the database |

| Age and sex of the patient | Not applicable |

| Event date | Day, month and year |

| Method of admission to the hospital | Ordinary/urgent/emergency |

| Type of setting | Emergency department, hospitalization (which encompasses short-term hospitalizations, such as day and week hospitals), outpatient services, consultation, teleconsultation, and laboratory services |

| Specialist area associated with the incident that led to the compensation request | Not applicable |

| Nature of the issue for which compensation is sought | Surgical errors (concerned invasive procedures, including endoscopic treatments and outpatient surgical procedures). Therapeutic errors involved the administration of drugs or other non-invasive forms of therapy. Diagnostic errors (pertaining to the recognition of a pathological condition, whether through laboratory or instrumental examinations, or by direct patient observation). For these three types of errors, the subcategories “commissive” (when the error consisted in performing an action that should not have been performed) and “omissive” (when the error involved omitting an action that should have been performed) were adopted. Information and consent (where it was not possible to demonstrate the acquisition of valid consent following comprehensive and proper information). Organizational deficiencies (when the error resulted from inadequacies in internal procedures within the institution, such as sterilization or transport procedures). Device defects (including cases in which the defect could potentially be attributed to the manufacturer) were also categorized. |

| Date of formulation of the first compensation request | Day, month, and year |

| Date of closure of the litigation | Day, month, and year |

| Type of damage referred to in the complaint | Generic, specific, or death |

| Technical consultancy on behalf of the party | Not applicable |

| Involvement of third parties and agreements with other hospitals | Not applicable |

| Medico-legal evaluation of the damage | CMC evaluation and recurrence of judicial technical consultancy |

| Path of the claim | The type and number of judicial and extrajudicial steps undertaken were considered, including the sequence in which these steps occurred |

| Claim outcome |

|

| Economic amount of the compensation definition | Amount in euros |

| Recurrence of rare diseases | All subjects were considered to have a rare disease if there was documentary evidence of them being affected by pathological conditions, or variants thereof, whose recurrence in the literature is reliably attested to be less than or equal to 1 in 2000. Subjects were classified as affected even if the rare disease in question was not related to the issue that led to the compensation claim. |

| ICPS results | The damage resulting from such liability has been categorized according to the International Classification of Patient Safety. This classification identifies the following levels:

|

| INJURY SPECIFICATION | N° OF CLAIMS | ACCEPTED | REJECTED | WITHOUT FOLLOW-UP | IN PROGRESS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENERIC | 133 | 41 | 40 | 35 | 17 |

| With TC | 48 | 18 | 14 | 5 | 11 |

| Without TC | 85 | 23 | 26 | 30 | 6 |

| SPECIFIC | 19 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| With TC | 16 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Without TC | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| DEATH | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| With TC | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Without TC | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| ICPS Results | N° | Median Compensation | Mean Compensation | Min Compensation | Max Compensation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 3 | 2200 | 5767.33 | 102 | 15,000 |

| Mild | 23 | 3371.75 | 7770.66 | 553.07 | 60,000 |

| Moderate | 13 | 16,085.95 | 20,638.66 | 8000 | 73,391.5 |

| Severe | 9 | 120,000 | 231,447.93 | 73,247.2 | 834,731 |

| Death | 3 | 321,500 | 264,782.15 | 54,954.45 | 417,892 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Defraia, B.; Faccioli, S.; Gori, E.; Gualco, B.; Grifoni, R.; Pacitti, M.; Pierro, F.; Lombardi, I.; Pinchi, V.; Focardi, M. Trends in Pediatric Malpractice Claims at a Tertiary Children’s Hospital. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2051. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162051

Defraia B, Faccioli S, Gori E, Gualco B, Grifoni R, Pacitti M, Pierro F, Lombardi I, Pinchi V, Focardi M. Trends in Pediatric Malpractice Claims at a Tertiary Children’s Hospital. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2051. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162051

Chicago/Turabian StyleDefraia, Beatrice, Simone Faccioli, Emanuele Gori, Barbara Gualco, Rossella Grifoni, Massimo Pacitti, Fortuna Pierro, Ilaria Lombardi, Vilma Pinchi, and Martina Focardi. 2025. "Trends in Pediatric Malpractice Claims at a Tertiary Children’s Hospital" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2051. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162051

APA StyleDefraia, B., Faccioli, S., Gori, E., Gualco, B., Grifoni, R., Pacitti, M., Pierro, F., Lombardi, I., Pinchi, V., & Focardi, M. (2025). Trends in Pediatric Malpractice Claims at a Tertiary Children’s Hospital. Healthcare, 13(16), 2051. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162051