The Impact of a Video-Educational and Tele-Supporting Program on the Caregiver–Stroke Survivor Dyad During Transitional Care (D-STEPS: Dyadic Support Through Tele-Health and Educational Programs in Stroke Care): A Longitudinal Study Protocol

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. AIMS

Secondary Objectives

- To assess changes in the quality of life (QoL) of stroke survivors and caregivers (both generic and stroke-specific) over time, and examine the relationship between caregiver preparedness and QoL. In particular, the study will evaluate QoL trajectories within the dyad during the 12 months following hospital discharge.

- To evaluate the impact of the intervention on caregiver burden, anxiety, and psychological distress, using validated instruments including the Caregiver Burden Inventory and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

- To investigate the effect of the intervention on additional caregiver-related outcomes, including perceived stroke recovery, social support, sleep quality, and stroke survivor outcomes such as hospitalizations, emergency service utilization, and mortality.

- To explore changes in stroke survivors’ functional status and disability, as measured by the Barthel Index and modified Rankin Scale (mRS).

- To examine the moderating role of dyadic mutuality in the relationship between caregiver preparedness and stroke survivor quality of life.

- To explore, through qualitative interviews, the lived experience of dyads, particularly regarding communication, adaptability, capability, and confidence during the transition from hospital to home.

1.2. Hypotheses

- H1: Stroke survivor–caregiver dyads who participate in the D-STEPS intervention will demonstrate a significant improvement in stroke-specific and generic quality of life (QoL) over a 12-month period.

- H2: Caregivers receiving the intervention will report significantly higher levels of preparedness (PATH-25) and mutuality (Mutuality Scale) compared to baseline.

- H3: The D-STEPS intervention will reduce caregiver burden (Caregiver Burden Inventory) and psychological distress (HADS) over time.

- H4: Stroke survivors receiving the intervention will show improved functional independence (Barthel Index) and reduced disability (mRS) over the 12-month follow-up.

- H5: The perceived quality of the dyadic relationship will moderate the effects of caregiver preparedness on stroke survivor QoL outcomes.

- H6 (Qualitative Hypothesis): We hypothesize that qualitative interviews will uncover enhanced dyadic communication, improved confidence and competence in caregiving, and an evolving sense of preparedness throughout the transition period, reflecting experiential dimensions that quantitative measures may not fully capture.

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling/Participants

2.2. Intervention and Data Collection

2.3. Video Content and Delivery

2.4. Monitoring Adherence and Nursing Support

2.5. Scope of Nursing Navigator Support

- Scheduling post-acute follow-up visits for the stroke survivor;

- Adapting and modifying physiotherapy sessions according to dyadic needs;

- Managing bureaucratic procedures and requests for assistive devices in accordance with disability regulations;

- Supporting pharmacological management and nutritional care;

- Assisting with the dyad’s mobility within and outside the local area;

- Addressing relational, health, communicative, and psychological challenges (in collaboration with specialized professionals);

- Promoting and supporting social and family reintegration;

- Collaborate on a multidisciplinary level with various healthcare professionals involved in the process of comprehensively improving the quality of life of stroke survivors, such as neurologists, physiatrists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, and nutritionists. Interact with the dyad’s social circle, such as family members, employers, and colleagues.

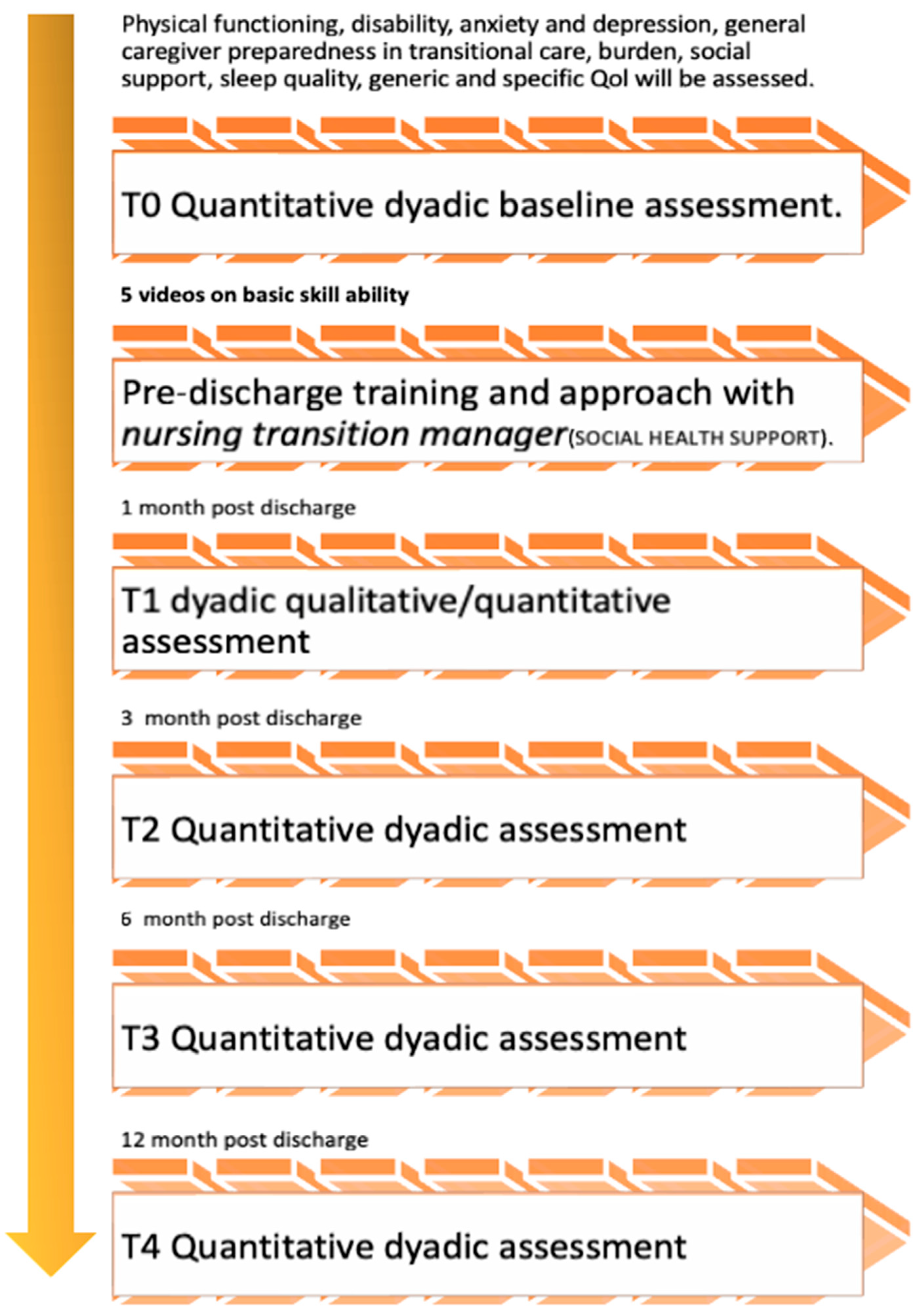

- T0: baseline quantitative investigation before the start of the intervention

- In-hospital viewing, prior to discharge, of five videos on mobilisation techniques and movement management of the stroke survivor.

- Prior to discharge, clarification, and presentation by the nurse in charge of transitional care, including providing the contact information of the nurse contact person, documents, and videos.

- T1: first qualitative and second quantitative survey to ascertain the dyad’s needs and effective support.

- T2: third quantitative survey to ascertain needs and effective dyad support.

- T3: fourth quantitative survey to ascertain needs and effective dyad support.

- T4: fifth quantitative survey to ascertain the needs and effective dyad support.

2.6. Baseline and Follow-Up Assessment

2.7. Outcomes Measured

2.8. Primary Outcomes

2.9. Secondary Outcomes

2.10. Qualitative Outcomes

2.11. Sample Size

2.12. Statistical and Qualitative Analysis

2.13. Expected Results

2.14. Ethical Consideration

3. Discussions

Strengths and Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Giannoni-Luza, S.; Navarro-Flores, A.; Rebello-Sanchez, I.; Parente, J.; Balbuena, A.; de Melo, P.S.; Otiniano-Sifuentes, R.; Rivera-Torrejon, O.; Abanto, C.; et al. Burden of Stroke and Population-Attributable Fractions of Risk Factors in Latin America and the Caribbean. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e027044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, D.; Brugnera, A.; Grego, A.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E.; Pucciarelli, G. Stroke disease-specific quality of life trajectories and their associations with caregivers’ anxiety, depression, and burden in stroke population: A longitudinal, multicentre study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2024, 23, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Stroke, Cerebrovascular Accident. 2023. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/stroke-cerebrovascular-accident/index.html#:~:text=Annually%2C%2015%20million%20people%20worldwide,cause%20is%20high%20blood%20pressure (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Thrift, A.G.; Thayabaranathan, T.; Howard, G.; Howard, V.J.; Rothwell, P.M.; Feigin, V.L.; Norrving, B.; Donnan, G.A.; Cadilhac, D.A. Global stroke statistics. Int. J. Stroke 2017, 12, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poomalai, G.; Prabhakar, S.; Sirala Jagadesh, N. Functional Ability and Health Problems of Stroke Survivors: An Explorative Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e33375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, S.A.; Venkatesh, P.K.; How, C.H. Long-term complications of stroke and secondary prevention: An overview for primary care physicians. Singap. Med. J. 2019, 60, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elloker, T.; Rhoda, A.J. The relationship between social support and participation in stroke: A systematic review. Afr. J. Disabil. 2018, 7, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Yadav, A.K.; Singh, V.K.; Pathak, A.; Chaurasia, R.N.; Mishra, V.N.; Joshi, D. Caregiver Burden in Caregivers of Stroke Survivors: A Hospital-Based Study. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2022, 25, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Lou, M.F.; Feng, T.H.; Chu, T.L.; Chen, Y.J.; Liu, H.E. Mediating effects of burden on quality of life for caregivers of first-time stroke patients discharged from the hospital within one year. BMC Neurol. 2018, 18, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostwald, S.K.; Bernal, M.P.; Cron, S.G.; Godwin, K.M. Stress experienced by stroke survivors and spousal caregivers during the first year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2009, 16, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, B.J.; Young, M.E.; Creasy, K.R.; Martz, C.; Eisenbrandt, L.; Brunny, J.N.; Cook, C. Improving Stroke Caregiver Readiness for Transition From Inpatient Rehabilitation to Home. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, K.M.; Ostwald, S.K.; Cron, S.G.; Wasserman, J. Long-term health-related quality of life of stroke survivors and their spousal caregivers. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2013, 45, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, B.J.; Young, M.E.; Cox, K.J.; Martz, C.; Creasy, K.R. The crisis of stroke: Experiences of patients and their family caregivers. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2011, 18, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Ellenbecker, C.H.; Chen, J.; Zhan, L.; Dalton, J. The influence of social environmental factors on rehospitalization among patients receiving home health care services. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2012, 35, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolley, J.; Smith, J.; DiGiacomo, M.; Salamonson, Y.; Davidson, P. The caregiving role following percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksson, A.; Arestedt, K. Exploring factors and caregiver outcomes associated with feelings of preparedness for caregiving in family caregivers in palliative care: A correlational, cross-sectional study. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.A.; Boult, C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 556–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Callaghan, G.; Fahy, M.; Murphy, P.; Langhorne, P.; Galvin, R.; Horgan, F. Effectiveness of interventions to support the transition home after acute stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.S.; Lee, C.S. The Theory of Dyadic Illness Management. J. Fam. Nurs. 2018, 24, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, B.J.; Reimold, A.E.; Coleman, S.W.; Guzik, A.K.; Russell, L.P.; Radman, M.D.; Johnson, A.M.; Duncan, P.W.; Bushnell, C.D.; Rosamond, W.D.; et al. Implementation of a Transitional Care Model for Stroke: Perspectives From Frontline Clinicians, Administrators, and COMPASS-TC Implementation Staff. Gerontologist 2020, 60, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.L.; Brown, J.; Willis, E.; Baldwin, A.; Harvey, C. Nurse Navigators—Champions of the National Rural and Remote Nursing Generalist Framework: A solution. Aust. J. Rural. Health 2024, 32, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystrom, K.V.; Neuschatz, K.; Petrucci, D.; Coppola, A.; Parker, R.L. From Stroke Code to Stroke Clinic; The Emerging Role of The Stroke Nurse Navigator. Stroke 2022, 53 (Suppl. S1), ATP32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.; Mardani, A.; Iloonkashkooli, R.; Khachian, A.; Glarcher, M.; Vaismoradi, M. The effect of hospital-to-home transitional care using a digital messaging application on the health outcomes of patients undergoing CABG and their family caregivers: A randomized controlled trial study protocol. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1224302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soh, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.; Toh, J.J.Y.; Li, X.; Wu, X.V. The effectiveness of tele-transitions of care interventions in high-risk older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 139, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, M.; Simeone, S.; Virgolesi, M.; Rago, C.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Pucciarelli, G. The Lived Experience of Caregivers in the Older Stroke Survivors’ Care Pathway during the Transitional Home Program-A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, T.; McCarthy, M.J.; Miller, E.L. Systematic Review of the Evidence for Stroke Family Caregiver and Dyad Interventions. Stroke 2022, 53, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaumann, S.; Ziller, C.; Paulissen, N.; Behrendt, F.; Suica, Z.; Cruts, B.; Gammerschlag, L.; Parmar, K.; Gerth, H.U.; Bonati, L.H.; et al. START-the Swiss tele-assisted rehabilitation and training program to support transition from inpatient to outpatient care in the subacute phase after a stroke: Feasibility, safety and performance evaluation. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1496170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghaddam, M.D.D.K.S.A. Effects of a Supportive Training on Caregiving Burden of Stroke Patients’ Caregivers after Discharge from an Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Arch. Anesth. Crit. Care 2025, 11, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, D.; Petrizzo, A.; Vellone, E.; Alvaro, R.; Pucciarelli, G. Impact of telehealth on stroke survivor-caregiver dyad in at-home rehabilitation: A systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 4003–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices; Scholar Commons: Austin, TX, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M.K.; Kahn, D.L.; Steeves, R.H. Hermeneutic Phenomenological Research: A Practical Guide for Nurse Researchers; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bannon, S.; Lester, E.G.; Gates, M.V.; McCurley, J.; Lin, A.; Rosand, J.; Vranceanu, A.M. Recovering together: Building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, H.; Lam, S.K.K.; Chien, W.T. Effects of a family-focused dyadic psychoeducational intervention for stroke survivors and their family caregivers: A pilot study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkle, J.L. Reliability and validity of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale for neuroscience nurses. Stroke 2014, 45, e32–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graven, L.J.; Glueckauf, R.L.; Regal, R.A.; Merbitz, N.K.; Lustria, M.L.A.; James, B.A. Telehealth Interventions for Family Caregivers of Persons with Chronic Health Conditions: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2021, 2021, 3518050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutron, I.; Guittet, L.; Estellat, C.; Moher, D.; Hrobjartsson, A.; Ravaud, P. Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamoun, C.; Harris, M.A. Impact of Stroke Survivors’ Physical Disability on the Presence of Caregiver Burden: A Systematic Review. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2022, 54, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Oliver, D.M.; Pacheco Rueda, A.; Viera-Ortiz, L.; Washington, K.T.; Oliver, D.P. The evidence supporting educational videos for patients and caregivers receiving hospice and palliative care: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellg, A.J.; Borrelli, B.; Resnick, B.; Hecht, J.; Minicucci, D.S.; Ory, M.; Ogedegbe, G.; Orwig, D.; Ernst, D.; Czajkowski, S.; et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol. 2004, 23, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camicia, M.; Lutz, B.J.; Harvath, T.; Kim, K.K.; Drake, C.; Joseph, J.G. Development of an Instrument to Assess Stroke Caregivers’ Readiness for the Transition Home. Rehabil. Nurs. 2020, 45, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, P.W.; Wallace, D.; Lai, S.M.; Johnson, D.; Embretson, S.; Laster, L.J. The stroke impact scale version 2.0. Evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke; A J. Cereb. Circ. 1999, 30, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellone, E.; Savini, S.; Fida, R.; Dickson, V.V.; Melkus, G.D.; Carod-Artal, F.J.; Rocco, G.; Alvaro, R. Psychometric evaluation of the Stroke Impact Scale 3.0. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.M.; Aben, L.; Heijenbrok-Kal, M.H.; Busschbach, J.J.; Ribbers, G.M. The relative effect of coping strategy and depression on health-related quality of life in patients in the chronic phase after stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. Off. J. UEMS Eur. Board Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 46, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaracz, K.; Grabowska-Fudala, B.; Górna, K.; Kozubski, W. Caregiving burden and its determinants in Polish caregivers of stroke survivors. Arch. Med. Sci. AMS 2014, 10, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Girolamo, G.; Rucci, P.; Scocco, P.; Becchi, A.; Coppa, F.; D’Addario, A.; Daru, E.; De Leo, D.; Galassi, L.; Mangelli, L.; et al. [Quality of life assessment: Validation of the Italian version of the WHOQOL-Brief]. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2000, 9, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md. State Med. J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Della Pietra, G.L.; Savio, K.; Oddone, E.; Reggiani, M.; Monaco, F.; Leone, M.A. Validity and reliability of the Barthel index administered by telephone. Stroke 2011, 42, 2077–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. III. Diagnosis and treatment. Scott. Med. J. 1957, 2, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, T.J.; Dawson, J.; Walters, M.R.; Lees, K.R. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: A systematic review. Stroke 2009, 40, 3393–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.R.; Tweed, A.E.; Metcalfe, M.S. A psychometric evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients diagnosed with end-stage renal disease. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. Br. Psychol. Soc. 2004, 43, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helvik, A.S.; Engedal, K.; Skancke, R.H.; Selbaek, G. A psychometric evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for the medically hospitalized elderly. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2011, 65, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, S.; Cosco, T.; Doyle, F.; Done, J.; Sacker, A. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: A meta confirmatory factor analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 74, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, M.A.; Muzzatti, B.; Altoe, G. Defining hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) structure by confirmatory factor analysis: A contribution to validation for oncological settings. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. /ESMO 2011, 22, 2330–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, M.; Guest, C. Application of a multidimensional caregiver burden inventory. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amelio, M.; Terruso, V.; Palmeri, B.; Di Benedetto, N.; Famoso, G.; Cottone, P.; Aridon, P.; Ragonese, P.; Savettieri, G. Predictors of caregiver burden in partners of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2009, 30, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchetti, L.; Uhunmwangho, E.; Dordoni, G.; Lorido, A.; Barbieri, S.; Bolognesi, A.G.; Gobbi, G.; Franchi, F. The subjective feeling of burden in caregivers of elderly with dementia: How to intervene? Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2009, 49 (Suppl. S1), 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, M.; Vellone, E.; Durante, A.; Biagioli, V.; Matarese, M. Psychometric evaluation of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) in people with chronic diseases. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2018, 54, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.S.; Andrykowski, M.A. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J. Psychosom. Res. 1998, 45, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archbold, P.G.; Stewart, B.J.; Greenlick, M.R.; Harvath, T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res. Nurs. Health 1990, 13, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucciarelli, G.; Buck, H.G.; Barbaranelli, C.; Savini, S.; Simeone, S.; Juarez-Vela, R.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Psychometric Characteristics of the Mutuality Scale in Stroke Patients and Caregivers. Gerontologist 2016, 56, e89–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, B.E.; Witkop, C.T.; Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaco, N.; Wagland, R.; Alexis, O.; Gavin, A.; Glaser, A.; Watson, E.K. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Dyadic Data in Health Research. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, J.; Kunkel, A. Qualitative approaches to dyadic data analyses in family communication research: An invited essay. J. Fam. Commun. 2015, 15, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddick, K.M.; Cross, V.; Vuoskoski, P.; Stew, G.; Galvin, K.T. Holding space and transitional space: Stroke survivors’ lived experience of being on an acute stroke unit. A hermeneutic phenomenological study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, D.; Trotta, F.; Pucciarelli, G.; Simeone, S.; Miccolis, R.; Cappitella, C.; Rotoli, D.; Rocco, M. The lived experiences of family members who visit their relatives in Covid-19 intensive care unit for the first time: A phenomenological study. Heart Lung 2022, 54, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Zhan, P. The Impact of Sample Attrition on Longitudinal Learning Diagnosis: A Prolog. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, B.; Muthén, L. Mplus. In Handbook of Item Response Theory; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 507–518. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X.; Pu, L.; Hu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, H. The impact of dyadic interventions on psycho-social outcomes for stroke patients and their caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1583621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashmdarfard, M.; Hejazi-Shirmard, M.; Amini, M. Effectiveness of non-medical interventions on caregiver burden of stroke survivors: A systematic review. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2025, 32, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, S.; Buck, H.G.; Dickson, V.V.; Simeone, S.; Pucciarelli, G.; Fida, R.; Matarese, M.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E. Quality of life in stroke survivor-caregiver dyads: A new conceptual framework and longitudinal study protocol. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Sha, K.H.; Ma, X.Y.; Li, X.M.; Zhang, M.H. Dyadic psycho-social interventions for stroke survivors and family caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 3707–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.S.; Glandon, G.L.; Elliott, T.R.; Giger, J.N.; Weaver, M. Caregiving problems and feelings experienced by family caregivers of stroke survivors the first month after discharge. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2004, 27, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhidayat, N.S.; Arafat, R.; Kadar, K.S. Experiences of stroke patients and the caregiver after discharge from hospital: A literature review. Enfermería Clínica 2021, 31, S817–S820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See Toh, W.X.S.; Lim, W.H.J.; Yobas, P.; Lim, S. The experiences of spousal and adult child caregivers of stroke survivors in transitional care: A qualitative systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 3897–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, K.L.; Stewart, B.J.; Archbold, P.G.; Caparro, M.; Mutale, F.; Agrawal, S. Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and preparedness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2008, 35, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Hartmann, M.; Wens, J.; Verhoeven, V.; Remmen, R. The effect of caregiver support interventions for informal caregivers of community-dwelling frail elderly: A systematic review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2012, 12, e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northouse, L.L.; Katapodi, M.C.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Mood, D.W. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.H.; Lyons, K.S.; Stewart, B.J.; Archbold, P.G.; Scobee, R. Does age make a difference in caregiver strain? Comparison of young versus older caregivers in early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; Sun, V.; Fujinami, R.; Sidhu, R.; Otis-Green, S.; Juarez, G.; Klein, L.; Ferrell, B. Family caregiver burden, skills preparedness, and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2013, 40, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, K.L.; Stewart, B.J.; Archbold, P.G. Mutuality and preparedness moderate the effects of caregiving demand on cancer family caregiver outcomes. Nurs. Res. 2007, 56, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Hochhalter, A.K.; Moudouni, D.K.; Smith, M.L.; Ory, M.G. Self-reported physical and mental health of older adults: The roles of caregiving and resources. Maturitas 2012, 71, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrizzo, A.; Lyons, K.S.; Bartoli, D.; Simeone, S.; Alvaro, R.; Lee, C.S.; Vellone, E.; Pucciarelli, G. The moderating role of caregiver preparedness on the relationship between depression and stroke-specific quality of life in stroke dyads: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2023, 22, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.S.; Elliott, T.R.; Weaver, M.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Giger, J.N. Telephone intervention with family caregivers of stroke survivors after rehabilitation. Stroke 2002, 33, 2060–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Xiao, L.D.; Chamberlain, D.; Newman, P.; Xie, S.; Tan, J.Y. The effect of transition care interventions incorporating health coaching strategies for stroke survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2039–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, D.; Lombardi, E.; Trotta, F.; Macripo, S.; Pucciarelli, G.; Francesco, P. Training and Support Needs in Transitional Care From Hospital to Home of the Health Care Professional-Caregiver-Stroke Survivor Triad: A Meta-Synthesis Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025, 34, 625–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Pucciarelli, G.; Mei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Vellone, E. The dyadic self-care experience of stroke survivors and their caregivers: A qualitative descriptive study. Health Expect. 2023, 26, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, F.; Karanikas, H.; Katsapi, A.; Tsana, M.; Tsoukas, V.; Koukoulas, G.; Drakopoulos, D.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Galanis, P. The Role of Sustainability in Telemedicine Services: The Case of the Greek National Telemedicine Network. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Lane, D.A.; Lenarczyk, R.; Boriani, G.; Doehner, W.; Benjamin, L.A.; Fisher, M.; Lowe, D.; Sacco, R.L.; Schnabel, R.; et al. Integrated care for optimizing the management of stroke and associated heart disease: A position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Council on Stroke. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2442–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, H.C.; Reinholdsson, M.; Lange, E.; Barna, S.; Palstam, A. Advancing sustainable healthcare through multidisciplinary stroke team rehabilitation. Front. Stroke 2025, 3, 1509831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullslett, M.K.; Ronchi, E.; Lundberg, L.; Larbi, D.; Lind, K.F.; Tayefi, M.; Ngo, P.D.; Sy, T.R.; Adib, K.; Hamilton, C. Telehealth development in the WHO European region: Results from a quantitative survey and insights from Norway. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 191, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, M.; Zonneveld, N.; Buchanan, F.; Kuluski, K. Patient Engagement in Integrated Care: What Matters and Why? Health Expect. 2025, 28, e70146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.J.; Song, Y.Y.; Wang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, W.Y.; Liu, W.J.; Liu, Y. Telerehabilitation for Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 2023, 3450312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Lamb, S.E.; Dixon-Woods, M.; McCulloch, P.; Wyatt, J.C.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Instruments | Time Data Collection | Administered to | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | C | |||

| General Characteristics | ||||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Ad hoc Questionnaire | T0 | X | X |

| Life condition (i.e., income, time of caregiving etc.) | Ad hoc Questionnaire | T0 | X | X |

| Comorbities | Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index | T0 | X | |

| Dimensions Assessed On The Dyad | ||||

| Site and type of stroke | Clinical data | T0 | X | |

| Physical functioning | Barthel Index | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | |

| Disability | modified Rankin scale (mRS), | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | |

| Anxiety and Depression | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | X |

| Caregiver preparedness in transitional care | preparedness assessment for the transition home (PATH-25) | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | |

| Burden | Caregiver Burden Inventory | T0, T1, T2, T3,T4; | X | |

| Social Support | Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | X |

| Relationship between stroke survivors and caregivers | Mutuality scale | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | X |

| Sleep quality | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | X |

| Generic Quality of life | WHOQOL-BREF (generic) | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | X |

| Specific Quality of Life | Stroke Impact Scale | T0, T1, T2, T3, T4; | X | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartoli, D.; Petrosino, F.; Nuccio, E.; Damico, V.; Rago, C.; Veronese, M.; Virgolesi, M.; Alvaro, R.; Vellone, E.; Lombardi, E.; et al. The Impact of a Video-Educational and Tele-Supporting Program on the Caregiver–Stroke Survivor Dyad During Transitional Care (D-STEPS: Dyadic Support Through Tele-Health and Educational Programs in Stroke Care): A Longitudinal Study Protocol. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162039

Bartoli D, Petrosino F, Nuccio E, Damico V, Rago C, Veronese M, Virgolesi M, Alvaro R, Vellone E, Lombardi E, et al. The Impact of a Video-Educational and Tele-Supporting Program on the Caregiver–Stroke Survivor Dyad During Transitional Care (D-STEPS: Dyadic Support Through Tele-Health and Educational Programs in Stroke Care): A Longitudinal Study Protocol. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162039

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartoli, Davide, Francesco Petrosino, Emanuela Nuccio, Vincenzo Damico, Cristiana Rago, Mayra Veronese, Michele Virgolesi, Rosaria Alvaro, Ercole Vellone, Eleonora Lombardi, and et al. 2025. "The Impact of a Video-Educational and Tele-Supporting Program on the Caregiver–Stroke Survivor Dyad During Transitional Care (D-STEPS: Dyadic Support Through Tele-Health and Educational Programs in Stroke Care): A Longitudinal Study Protocol" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162039

APA StyleBartoli, D., Petrosino, F., Nuccio, E., Damico, V., Rago, C., Veronese, M., Virgolesi, M., Alvaro, R., Vellone, E., Lombardi, E., & Pucciarelli, G. (2025). The Impact of a Video-Educational and Tele-Supporting Program on the Caregiver–Stroke Survivor Dyad During Transitional Care (D-STEPS: Dyadic Support Through Tele-Health and Educational Programs in Stroke Care): A Longitudinal Study Protocol. Healthcare, 13(16), 2039. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162039