A Validation Study of the COPSOQ III Greek Questionnaire for Assessing Psychosocial Factors in the Workplace

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Sample

2.3. The Greek Version of COPSOQ III

2.4. Statistical Analyses

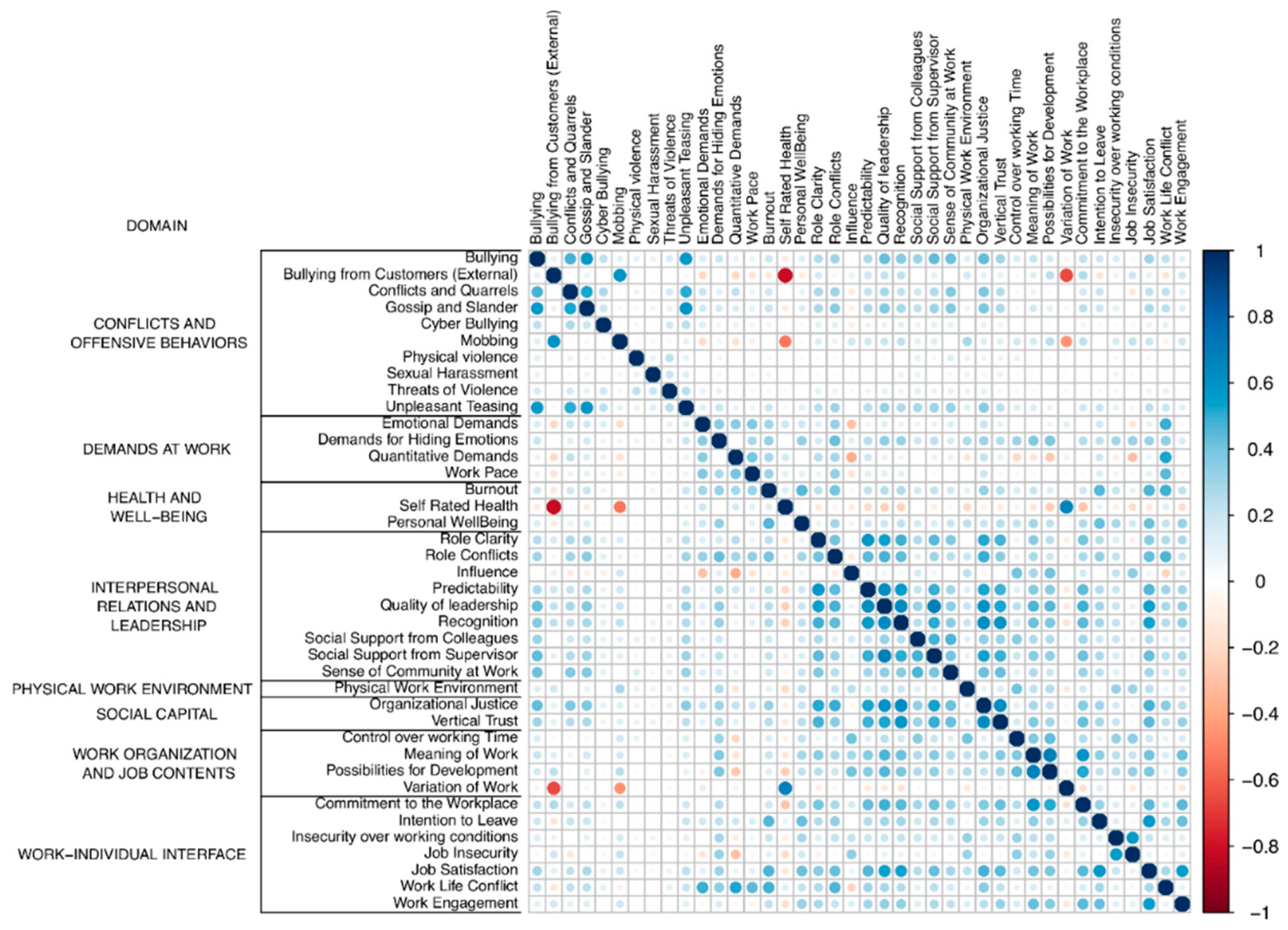

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Magnavita, N.; Soave, P.M.; Ricciardi, W.; Antonelli, M. Occupational stress and mental health among anaesthetists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Prado-Gascó, V.; Soto-Rubio, A. Psychosocial risks, work engagement, and job satisfaction of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 566896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, H.; Milaković, M.; Bubaš, M.; Bekavac, P.; Bekavac, B.; Bucić, L.; Čvrljak, J.; Capak, M.; Jeličić, P. Psychosocial risks emerged from COVID-19 pandemic and workers’ mental health. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1148634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che Huei, L.; Ya-Wen, L.; Chiu Ming, Y.; Li Chen, H.; Jong Yi, W.; Ming Hung, L. Occupational health and safety hazards faced by healthcare professionals in Taiwan: A systematic review of risk factors and control strategies. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120918999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigotti, T.; Yang, L.Q.; Jiang, Z.; Newman, A.; De Cuyper, N.; Sekiguchi, T. Work-related psychosocial risk factors and coping resources during the COVID-19 crisis. Appl. Psychol. Psychol. Appliquée 2021, 70, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oikonomou, V.; Gkintoni, E.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Karademas, E.C. Quality of Life and Incidence of Clinical Signs and Symptoms among Caregivers of Persons with Mental Disorders: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Rubio, A.; Giménez-Espert, M.D.C.; Prado-Gascó, V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Molen, H.F.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; de Groene, G. Work-related psychosocial risk factors for stress-related mental disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E.; Kourkoutas, E.; Yotsidi, V.; Stavrou, P.D.; Prinianaki, D. Clinical Efficacy of Psychotherapeutic Interven-tions for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, P.; Gkiouleka, A. A scoping review of psychosocial risks to health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, Y.; Metzler, Y.A.; Bellingrath, S.; Müller, A. A systematic overview on the risk effects of psychosocial work characteristics on musculoskeletal disorders, absenteeism, and workplace accidents. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 95, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E.; Skokou, M.; Gourzis, P. Integrating Clinical Neuropsychology and Psychotic Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Analysis of Cognitive Dynamics, Interventions, and Underlying Mechanisms. Medicina 2024, 60, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrenovic, B.; Jianguo, D.; Khudaykulov, A.; Khan, M.A.S. Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: A job performance model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Ortiz, P.S. Neuropsychology of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Clinical Setting: A Systematic Evaluation. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dar, T.; Radfar, A.; Abohashem, S.; Pitman, R.; Tawakol, A.; Osborne, M. Psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.T.; Bentley, T.; Nguyen, D. Psychosocial work environment, work engagement, and employee commitment: A moderated, mediation model. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.Z.A.R.; Zalam, W.Z.M.; Foster, B.; Afrizal, T.; Johansyah, M.D.; Saputra, J.; Bakar, A.A.; Dagang, M.M.; Ali, S.N.M. Psychosocial work environment and teachers’ psychological well-being: The moderating role of job control and social support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Dollard, M.F.; Taris, T.W. Organizational context matters: Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to team and individual motivational functioning. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östergård, K.; Kuha, S.; Kanste, O. Health-care leaders’ and professionals’ experiences and perceptions of compassionate leadership: A mixed-methods systematic review. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2023, 37, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G.N. Associations between Traditional and Digital Leadership in Academic Environment: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitshwarelo, T.; Koen, M.P.; Rakhudu, M.A. Strengths employed by resilient nurse managers in dealing with workplace stressors in public hospitals. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 13, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinane, E.; Bardoel, E.A.; Pervan, S. CEOs, leaders and managing mental health: A tension-centered approach. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 3157–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G.N. Transition from Educational Leadership to e-Leadership: A Data Analysis Report from TEI of Western Greece. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P. The Nexus of Change Management and Sustainable Leadership: Shaping Organizational Social Impact. In Diversity, Equity and Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G.N. Transformational Leadership and Digital Skills in Higher Education Institutes: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Antonopoulou, H. Neuroleadership an Asset in Educational Settings: An Overview. Emerg. Sci. J. 2022, 6, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, R.; Rogers, L.; Khurshid, Z.; De Brún, A.; Nicholson, E.; O’Shea, M.; Ward, M.; McAuliffe, E. A systematic review exploring the impact of focal leader behaviours on health care team performance. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, N.S.; Jalili, M.; Sandars, J.; Gandomkar, R. Leadership behaviors in health care action teams: A systematized review. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2022, 36, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsopoulou, I.; Grace, E.; Gkintoni, E.; Olff, M. Validation of the Global Psychotrauma Screen for adolescents in Greece. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2024, 8, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greece. Law 3850/2010—Code of Laws for the Health and Safety of Workers [Κώδικας νόμων για την υγεία και την ασφάλεια των εργαζομένων]. Government Gazette A’ 84/2010 Jun 2. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/n-38502010-fek-84a-262010 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Greece. Law 4808/2021—For the Protection of Labour; Establishment of Independent Authority “Labour Inspectorate”; Ratification of ILO Convention No. 190. Government Gazette A’ 101. 2021 Jun 19. Available online: https://www.elinyae.gr/ethniki-nomothesia/n-48082021-fek-101a-1962021 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Burr, H.; Berthelsen, H. The third version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Saf. Health Work. 2019, 10, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nübling, M.; Burr, H. COPSOQ International Network: Co-operation for research and assessment of psychosocial factors at work. Public Health Forum 2014, 22, 18.e1–18.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T.; Marsh, H.W. Validating the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ-II) using Set-ESEM: Identifying psychosocial risk factors in a sample of school principals. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosário, S.A. The Portuguese long version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire II (COPSOQ II)—A validation study. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2017, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramkissoon, A.; Shukla, P. Dissecting the effect of workplace exposures on workers’ rating of psychological health and safety. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Hannerz, H.; Høgh, A.; Borg, V. The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire—A tool for the assessment and improvement of the psychosocial work environment. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2005, 31, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejtersen, J.H.; Kristensen, T.S.; Borg, V.; Bjorner, J.B. The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38 (Suppl. S3), 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincke, H.V.; Theorell, T. COPSOQ III in Germany: Validation of a standard instrument to measure psychosocial factors at work. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2021, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelsen, H.; Westerlund, H.; Bergström, G.; Burr, H. Validation of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire Version III and establishment of benchmarks for psychosocial risk management in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahan, C.B.; Aydın, H. A novel version of Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire-3: Turkish validation study. Arch. Environ. Occup. Health 2018, 73, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naring, G.; van Scheppingen, A. Using health and safety monitoring routines to enhance sustainable employability. Work 2021, 70, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsakis, N.E.; Nübling. Employability in the 21st Century. The Greek COPSOQ v.3 Validation Study, a post crisis assessment of the Psychosocial Risks. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Sustainable Employability, Leuven, Belgium, 12–13 September 2018; p. 63. Available online: https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.12793789 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Kotsakis, A. Conceptual Framework Development and Systemic Modelling for the Assessment of Strategic Organizational Change in Public Sector Entities. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Piraeus, Piraeus, Greece, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsakis, A.; Avraam, D. The COPSOQ III Greek Validation Study [Data Set]; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 10075-3; Ergonomische Grundlagen Bezüglich Psychischer Arbeitsbelastung_- Teil_3: Grundsätze und Anforderungen an Verfahren zur Messung und Erfassung Psychischer Arbeitsbelastung. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO/IEC 27018:2019; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Code of Practice for Protection of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) in Public Clouds Acting as PII Processors. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/76559.html (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (US). NIST Special Publication 800-53 Rev. 5—Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations; NIST: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizopoulos, D. ltm: An R package for latent variable modelling and item response theory analyses. J. Stat. Softw. 2006, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamer, M.; Lemon, J.; Fellows, I.; Singh, P. Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement. 2012. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/irr/irr.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Steiner, M.; Grieder, S. EFAtools: An R package with fast and flexible implementations of exploratory factor analysis tools. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, D.A.; Gyurko, C.C. The global nursing faculty shortage: Status and solutions for change. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2013, 45, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselhorn, H.M.; Tackenberg, P.; Kuemmerling, A.; Wittenberg, J.; Simon, M.; Conway, P.M.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Beermann, B.; Büscher, A.; Camerino, D.; et al. Nurses’ health, age and the wish to leave the profession--findings from the European NEXT-Study. Med. Lav. 2006, 97, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, D.R.; Griep, R.H.; Rotenberg, L. Intention to leave profession, psychosocial environment and self-rated health among registered nurses from large hospitals in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derycke, H.; Vlerick, P.; Clays, E. Impact of the effort-reward imbalance model on intent to leave among Belgian health care workers: A prospective study. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; While, A.E.; Barriball, K.L. Job satisfaction among nurses: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2005, 42, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellenbecker, C.H.; Porell, F.W. Predictors of home healthcare nurse retention. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2008, 40, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Ora, C.; Ball, J.; Recio-Saucedo, A.; Griffiths, P. Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Hum. Resour. Health 2020, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargagliotti, A.L. Work engagement in nursing: A concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2012, 68, 1414–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G. Leadership Types and Digital Leadership in Higher Education: Behavioural Data Analysis from University of Patras in Greece. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Kourkoutas, E.; Vassilopoulos, S.P.; Mousi, M. Clinical Intervention Strategies and Family Dynamics in Adolescent Eating Disorders: A Scoping Review for Enhancing Early Detection and Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. Clinical neuropsychological characteristics of bipolar disorder, with a focus on cognitive and linguistic pattern: A conceptual analysis. F1000Research 2023, 12, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malliarou, M.; Kotsakis, A. Editorial: Psychosocial work environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1272290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzenetidis, V.; Kotsakis, A.; Gouva, M.; Tsaras, K.; Malliarou, M. The relationship between psychosocial work environment and nurses’ performance, on studies that used the validated instrument Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ): An empty scoping review. Pol. Merkur. Lek. 2023, 51, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzenetidis, V.; Kotsakis, A.; Gouva, M.; Tsaras, K.; Malliarou, M. Examining psychosocial risks and their impact on nurses’ safety attitudes and medication error rates: A cross-sectional study. AIMS Public Health 2025, 12, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Sample of COPSOQ-Database | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Gender | Male | 1105 | 50.5 |

| Female | 1084 | 49.5 | |

| Age groups | up to 24 | 693 | 31.7 |

| 25–34 | 377 | 17.2 | |

| 35–44 | 673 | 30.7 | |

| 45–54 | 376 | 17.2 | |

| 55 and more | 70 | 3.2 | |

| Supervisor | No (jobs with no supervisors) | 384 | 17.5 |

| Yes | 470 | 21.5 | |

| No (jobs with supervisors) | 1335 | 61.0 | |

| Interface with external clients | No, never | 923 | 42.2 |

| Yes, less than 1 time per day (on average) | 103 | 4.7 | |

| Yes, 1 to 5 times per day (on average) | 151 | 6.9 | |

| Yes, 6 to 14 times per day (on average) | 233 | 10.6 | |

| Yes, 15 or more times per day (average) | 779 | 35.6 | |

| Sector | Public | 954 | 43.6 |

| Private | 1235 | 56.4 | |

| Profession a | Admin, leading | 336 | 15.3 |

| Tech, leading | 190 | 8.7 | |

| Workers | 202 | 9.2 | |

| Tech: engineers | 56 | 2.6 | |

| Tech: technicians | 274 | 12.5 | |

| Admin, not leading | 567 | 25.9 | |

| Tech, not leading | 97 | 4.4 | |

| Other professions. | 467 | 21.3 | |

| Scale | n | a | ICC | M | SD | Floor Effect (%) | Ceiling Effect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout | 5 | 0.73 | 0.32 | 43.64 | 26.71 | 12.41 | 5.24 |

| Bullying | 2 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 13.47 | 20.52 | 61.06 | 1.1 |

| Bullying from Customers (External) | 9 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 64.87 | 38.96 | 16.33 | 46.34 |

| Role Clarity | 3 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 20.1 | 21.94 | 43 | 1.48 |

| Role Conflicts | 3 | 0.82 | 0.6 | 49.38 | 29.02 | 13.11 | 10.43 |

| Conflicts and Quarrels | 1 | - | - | 10.27 | 17.23 | 67.98 | 0.23 |

| Control over Working Time | 2 | 0.49 | 0.3 | 38.01 | 29.55 | 18.82 | 10 |

| Commitment to the Workplace | 2 | 0.68 | 0.3 | 33.22 | 30.49 | 32.09 | 7.51 |

| Emotional Demands | 2 | 0.57 | 0.09 | 36.45 | 33.22 | 35.38 | 7.72 |

| Self-Rated Health | 1 | - | - | 29.56 | 31.75 | 23.98 | 4.93 |

| Gossip and Slander | 1 | - | - | 18.73 | 24.18 | 50.53 | 2.1 |

| Demands for Hiding Emotions | 2 | 0.73 | 0.5 | 57.47 | 32.54 | 12.79 | 22.09 |

| Cyber Bullying | 1 | - | - | 0.9 | 6.1 | 97.26 | 0.05 |

| Influence | 3 | 0.8 | 0.55 | 63.32 | 28.14 | 3.33 | 25.17 |

| Intention to Leave | 2 | 0.81 | 0.68 | 16.21 | 22.79 | 55 | 2.49 |

| Insecurity over Working Conditions | 3 | 0.65 | 0.28 | 32.22 | 32.45 | 37.43 | 8.82 |

| Job Insecurity | 3 | 0.8 | 0.56 | 47.99 | 34.38 | 21.08 | 17.36 |

| Job Satisfaction | 7 | 0.88 | 0.47 | 33.35 | 24.18 | 18.67 | 3 |

| Organizational Justice | 2 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 37.6 | 25.29 | 15.19 | 4.29 |

| Mobbing | 5 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 58.38 | 46.47 | 35.79 | 55.29 |

| Meaning of Work | 2 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 25.23 | 26.31 | 38.97 | 3.63 |

| Possibilities for Development | 2 | 0.84 | 0.72 | 41.83 | 31.56 | 20.05 | 12.43 |

| Predictability | 2 | 0.68 | 0.34 | 42.1 | 29.49 | 16.49 | 9.48 |

| Physical Violence | 1 | - | - | 0.3 | 3.53 | 99.18 | 0 |

| Personal Well-being | 6 | 0.87 | 0.47 | 24.96 | 26.89 | 43.17 | 2.22 |

| Physical Work Environment | 6 | 0.83 | 0.4 | 36.62 | 35.85 | 37.87 | 11.69 |

| Quantitative Demands | 3 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 34 | 27.19 | 26.13 | 2.68 |

| Quality of Leadership | 4 | 0.87 | 0.56 | 43.18 | 29.97 | 15.63 | 11.58 |

| Recognition | 1 | - | - | 40.81 | 28.81 | 16.26 | 8.59 |

| Social Support from Colleagues | 3 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 31.37 | 26.76 | 26.33 | 4.84 |

| Sexual Harassment | 1 | - | - | 0.32 | 3.1 | 98.81 | 0 |

| Social Support from Supervisor | 4 | 0.76 | 0.37 | 30.38 | 28.25 | 31.43 | 5.11 |

| Sense of Community at Work | 2 | 0.7 | 0.54 | 13.62 | 17.07 | 54.59 | 0.34 |

| Vertical Trust | 2 | 0.64 | 0.47 | 27.07 | 22.22 | 26.79 | 1.69 |

| Threats of Violence | 1 | - | - | 0.7 | 4.7 | 97.58 | 0 |

| Unpleasant Teasing | 1 | - | - | 9.86 | 18.58 | 71.63 | 0.73 |

| Variation of Work | 1 | - | - | 10.31 | 18.25 | 4.39 | 0.59 |

| Work Life Conflict | 7 | 0.84 | 0.34 | 34.65 | 33.35 | 37.34 | 8.61 |

| Work Engagement | 3 | 0.69 | 0.36 | 27.25 | 22.43 | 26.62 | 1.37 |

| Work Pace | 2 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 71.55 | 18.65 | 0.48 | 17.95 |

| Psychosocial Work Factors a | Factor Loading b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Bullying | 0.32 | 0.68 | |||

| Bullying from Customers (External) | 0.85 | ||||

| Role Clarity | 0.67 | ||||

| Role Conflicts | 0.41 | 0.53 | |||

| Conflicts and Quarrels | 0.60 | ||||

| Control over Working Time | 0.63 | ||||

| Commitment to the Workplace | 0.62 | ||||

| Emotional Demands | 0.60 | ||||

| Gossip and Slander | 0.64 | ||||

| Demands for Hiding Emotions | 0.51 | 0.40 | |||

| Cyber Bullying | 0.31 | ||||

| Influence | 0.52 | 0.36 | |||

| Insecurity over Working Conditions | 0.53 | ||||

| Job Insecurity | 0.67 | ||||

| Organizational Justice | 0.67 | ||||

| Mobbing | 0.61 | ||||

| Meaning of Work | 0.58 | 0.45 | |||

| Possibilities for Development | 0.51 | 0.56 | |||

| Predictability | 0.68 | ||||

| Physical Violence | |||||

| Physical Work Environment | 0.50 | ||||

| Quantitative Demands | −0.39 | 0.58 | |||

| Quality of Leadership | 0.75 | ||||

| Recognition | 0.69 | ||||

| Social Support from Colleagues | 0.39 | 0.31 | |||

| Sexual Harassment | |||||

| Social Support from Supervisor | 0.67 | ||||

| Sense of Community at Work | 0.48 | 0.39 | |||

| Vertical Trust | 0.67 | ||||

| Threats of Violence | |||||

| Unpleasant Teasing | 0.74 | ||||

| Variation of Work | −0.71 | ||||

| WorkLife Conflict | 0.71 | ||||

| Work Pace | 0.59 | ||||

| Effects a | Factor Loading b | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Self-Rated Health | −0.55 | |

| Intention to Leave | 0.70 | |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.73 | 0.47 |

| Personal Well-being | 0.62 | |

| Burnout | 0.69 | |

| Work Engagement | 0.51 | 0.44 |

| Outcome | Self-Rated Health | Intention to Leave | Job Satisfaction | Personal Well-Being | Burnout | Work Engagement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | |||||||

| Bullying | −0.022 (0.031) | −0.028 (0.027) | 0.012 (0.021) | −0.023 (0.027) | −0.034 (0.023) | −0.086 (0.023) *♦ | |

| Bullying from Customers (External) | −0.341 (0.018) *♦ | −0.120 (0.016) *♦ | −0.028 (0.012) * | −0.116 (0.016) *♦ | −0.039 (0.014) * | 0.048 (0.013) *♦ | |

| Role Clarity | 0.068 (0.033) * | −0.044 (0.030) | −0.060 (0.023) * | −0.143 (0.029) *♦ | 0.025 (0.025) | 0.001 (0.025) | |

| Role Conflicts | 0.019 (0.024) | 0.117 (0.021) *♦ | 0.079 (0.016) *♦ | 0.109 (0.021) *♦ | 0.082 (0.018) *♦ | 0.039 (0.018) * | |

| Conflicts and Quarrels | 0.021 (0.033) | 0.052 (0.029) | 0.025 (0.022) | 0.025 (0.029) | 0.039 (0.025) | 0.039 (0.024) | |

| Control over Working Time | −0.032 (0.024) | −0.018 (0.021) | −0.047 (0.016) * | 0.011 (0.021) | 0.012 (0.018) | −0.013 (0.018) | |

| Commitment to the Workplace | −0.067 (0.024) * | 0.141 (0.022) *♦ | 0.086 (0.016) *♦ | 0.114 (0.021) *♦ | 0.031 (0.018) | 0.135 (0.018) *♦ | |

| Emotional Demands | 0.072 (0.022) *♦ | 0.017 (0.020) | −0.005 (0.015) | 0.086 (0.020) *♦ | 0.039 (0.017) * | −0.004 (0.017) | |

| Gossip and Slander | −0.059 (0.025) * | −0.010 (0.022) | 0.011 (0.017) | 0.001 (0.022) | 0.021 (0.019) | −0.017 (0.018) | |

| Demands for Hiding Emotions | 0.041 (0.021) | 0.005 (0.019) | 0.007 (0.014) | 0.063 (0.018) *♦ | 0.027 (0.016) | −0.020 (0.015) | |

| Cyber Bullying | −0.078 (0.075) | −0.126 (0.067) | 0.048 (0.051) | 0.027 (0.066) | −0.030 (0.057) | 0.001 (0.055) | |

| Influence | 0.191 (0.021) *♦ | 0.021 (0.019) | 0.041 (0.014) * | 0.033 (0.018) | 0.059 (0.016) *♦ | 0.073 (0.016) *♦ | |

| Insecurity over Working Conditions | −0.038 (0.024) | 0.077 (0.021) *♦ | 0.015 (0.016) | 0.125 (0.021) *♦ | 0.029 (0.018) | −0.024 (0.018) | |

| Job Insecurity | 0.040 (0.021) | −0.070 (0.018) *♦ | −0.009 (0.014) | 0.018 (0.018) | 0.082 (0.016) *♦ | 0.038 (0.015) * | |

| Organizational Justice | 0.057 (0.031) | 0.006 (0.028) | 0.057 (0.021) * | −0.001 (0.027) | 0.056 (0.023) * | −0.011 (0.023) | |

| Mobbing | −0.021 (0.012) | 0.026 (0.011) * | 0.037 (0.008) *♦ | 0.026 (0.011) * | 0.019 (0.009) * | 0.018 (0.009) * | |

| Meaning of Work | −0.002 (0.027) | 0.148 (0.024) *♦ | 0.028 (0.018) | 0.082 (0.023) *♦ | 0.023 (0.020) | 0.121 (0.020) *♦ | |

| Possibilities for Development | −0.093 (0.023) *♦ | 0.020 (0.021) | 0.046 (0.016) * | −0.017 (0.020) | −0.012 (0.018) | 0.028 (0.017) | |

| Predictability | 0.000 (0.026) | −0.021 (0.023) | 0.042 (0.018) * | 0.038 (0.023) | −0.033 (0.020) | 0.009 (0.019) | |

| Physical violence | −0.168 (0.126) | −0.304 (0.113) * | 0.008 (0.086) | −0.040 (0.111) | 0.042 (0.095) | 0.116 (0.094) | |

| Physical Work Environment | 0.006 (0.020) | −0.026 (0.018) | 0.065 (0.014) *♦ | 0.077 (0.018) *♦ | 0.007 (0.015) | 0.015 (0.015) | |

| Quantitative Demands | 0.069 (0.027) * | 0.081 (0.024) *♦ | 0.019 (0.018) | −0.025 (0.023) | 0.095 (0.020) *♦ | 0.053 (0.020) * | |

| Quality of Leadership | −0.115 (0.031) *♦ | −0.023 (0.027) | 0.115 (0.021) *♦ | −0.030 (0.027) | −0.036 (0.023) | 0.014 (0.023) | |

| Recognition | −0.038 (0.023) | 0.064 (0.020) * | 0.095 (0.016) *♦ | 0.013 (0.020) | 0.032 (0.017) | 0.029 (0.017) | |

| Social Support from Colleagues | 0.162 (0.032) *♦ | 0.016 (0.028) | 0.031 (0.021) | 0.026 (0.028) | 0.067 (0.024) * | −0.051 (0.023) * | |

| Sexual Harassment | −0.074 (0.143) | −0.087 (0.128) | −0.027 (0.097) | −0.013 (0.125) | 0.197 (0.108) | −0.141 (0.106) | |

| Social Support from Supervisor | 0.056 (0.032) | 0.043 (0.029) | 0.004 (0.022) | −0.063 (0.028) * | 0.004 (0.024) | 0.041 (0.024) | |

| Sense of Community at Work | −0.054 (0.037) | 0.013 (0.033) | 0.028 (0.025) | 0.119 (0.033) *♦ | −0.003 (0.028) | 0.098 (0.028) *♦ | |

| Vertical Trust | 0.050 (0.032) | 0.030 (0.029) | 0.054 (0.022) * | 0.105 (0.028) *♦ | 0.033 (0.024) | 0.087 (0.024) *♦ | |

| Threats of Violence | −0.059 (0.099) | 0.063 (0.089) | 0.018 (0.068) | −0.121 (0.087) | −0.084 (0.075) | −0.127 (0.074) | |

| Unpleasant Teasing | −0.019 (0.032) | 0.081 (0.029) * | −0.035 (0.022) | −0.019 (0.028) | 0.002 (0.025) | 0.025 (0.024) | |

| Variation of Work | 0.706 (0.030) *♦ | 0.056 (0.026) * | 0.037 (0.020) | −0.045 (0.026) | 0.026 (0.022) | 0.020 (0.022) | |

| WorkLife Conflict | 0.018 (0.028) | 0.063 (0.025) * | 0.048 (0.019) * | 0.031 (0.024) | 0.207 (0.021) *♦ | 0.015 (0.021) | |

| Work Pace | 0.376 (0.025) *♦ | −0.019 (0.023) | 0.035 (0.017) * | 0.034 (0.022) | 0.171 (0.019) *♦ | 0.012 (0.019) | |

| R2 | 0.795 | 0.558 | 0.874 | 0.711 | 0.901 | 0.794 | |

| R2 adjusted | 0.791 | 0.551 | 0.872 | 0.706 | 0.899 | 0.790 | |

| Dependent Scale | Total Model Fit | Model Fit with Top five a Predictors | Top Five a Predictors | Estimated Coefficient (Std Error) b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | AIC (df) | R2 | AIC (df) | |||

| Self-Rated Health | 0.795 | 13,107.96 (34) | 0.777 | 13,229.95 (5) | Variation of Work Bullying from Customers (External) Work Pace Influence Social Support from Colleagues | 0.744 (0.030) −0.385 (0.015) 0.487 (0.017) 0.120 (0.018) 0.089 (0.025) |

| Intention to Leave | 0.564 | 12,599.47 (40) | 0.524 | 12,723.22 (5) | Bullying from Customers (External) Commitment to the Workplace Meaning of Work Role Conflicts Job Insecurity | −0.106 (0.011) 0.195 (0.021) 0.157 (0.020) 0.256 (0.014) −0.016 (0.013) |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.876 | 11,411.47 (40) | 0.861 | 11,598.03 (5) | Recognition Quality of Leadership Commitment to the Workplace Role Conflicts Physical Work Environment | 0.140 (0.014) 0.200 (0.017) 0.150 (0.014) 0.177 (0.013) 0.109 (0.012) |

| Personal Well-being | 0.718 | 12,491.16 (40) | 0.673 | 12,745.61 (5) | Bullying from Customers (External) Insecurity over Working Conditions Commitment to the Workplace Role Conflicts Role Clarity | −0.046 (0.010) 0.249 (0.017) 0.226 (0.018) 0.270 (0.015) −0.112 (0.025) |

| Burnout | 0.905 | 11,798.87 (40) | 0.892 | 12,013.86 (5) | Work Life Conflict Work Pace Job Insecurity Quantitative Demands Role Conflicts | 0.244 (0.020) 0.255 (0.015) 0.130 (0.011) 0.074 (0.019) 0.153 (0.015) |

| Work Engagement | 0.806 | 11,681.94 (40) | 0.774 | 11,943.91 (5) | Commitment to the Workplace Meaning of Work Influence Bullying Vertical Trust | 0.213 (0.017) 0.116 (0.017) 0.165 (0.009) −0.005 (0.017) 0.206 (0.019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kotsakis, A.; Avraam, D.; Malliarou, M.; Soteriades, E.S.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Galanakis, M.; Sfakianakis, M. A Validation Study of the COPSOQ III Greek Questionnaire for Assessing Psychosocial Factors in the Workplace. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161980

Kotsakis A, Avraam D, Malliarou M, Soteriades ES, Halkiopoulos C, Galanakis M, Sfakianakis M. A Validation Study of the COPSOQ III Greek Questionnaire for Assessing Psychosocial Factors in the Workplace. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161980

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotsakis, Aristomenis, Demetris Avraam, Maria Malliarou, Elpidoforos S. Soteriades, Constantinos Halkiopoulos, Michael Galanakis, and Michael Sfakianakis. 2025. "A Validation Study of the COPSOQ III Greek Questionnaire for Assessing Psychosocial Factors in the Workplace" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161980

APA StyleKotsakis, A., Avraam, D., Malliarou, M., Soteriades, E. S., Halkiopoulos, C., Galanakis, M., & Sfakianakis, M. (2025). A Validation Study of the COPSOQ III Greek Questionnaire for Assessing Psychosocial Factors in the Workplace. Healthcare, 13(16), 1980. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161980