Loneliness and Isolation in the Era of Telework: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges for Organizational Success

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Selection and Extraction

3. Results

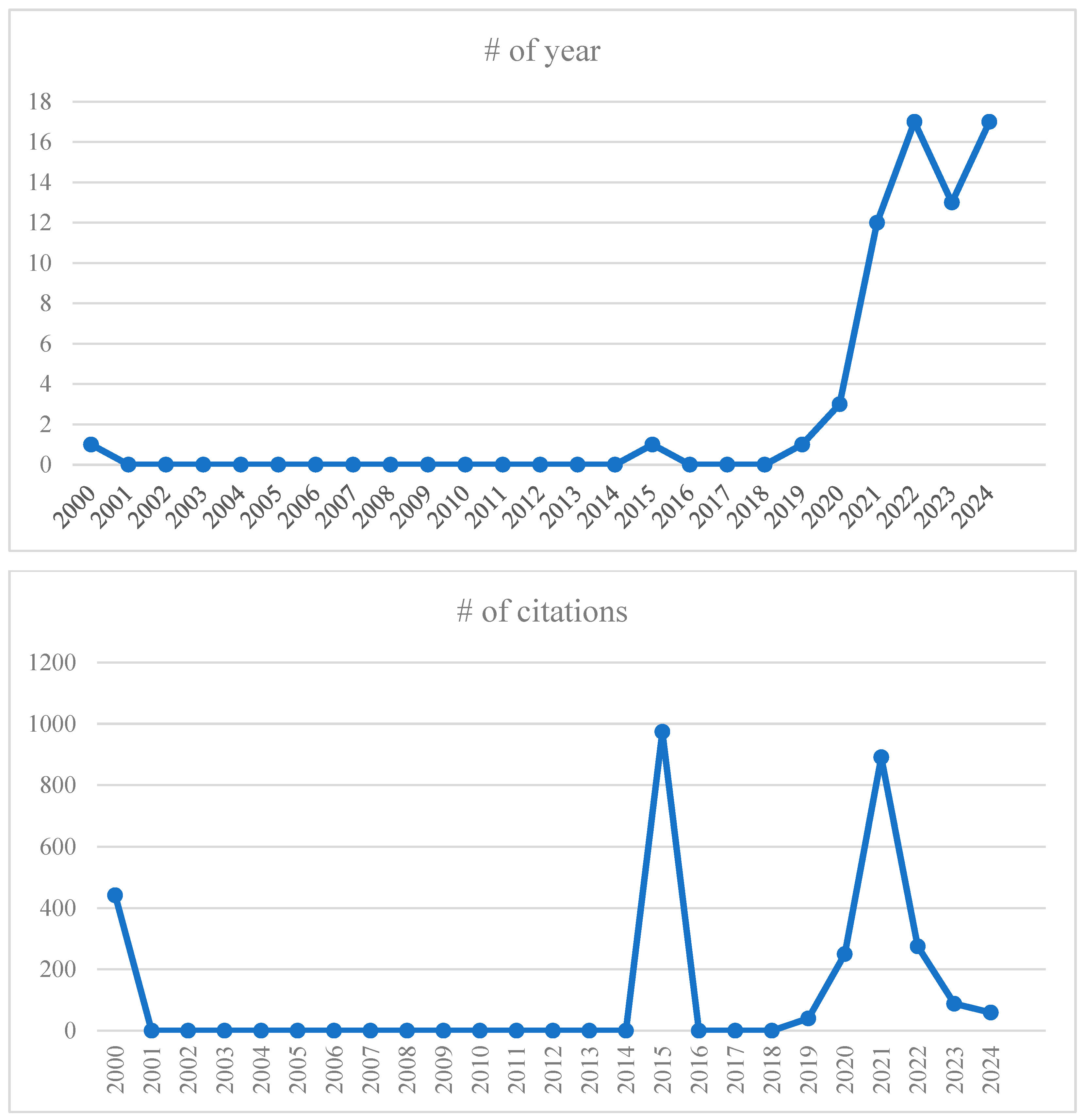

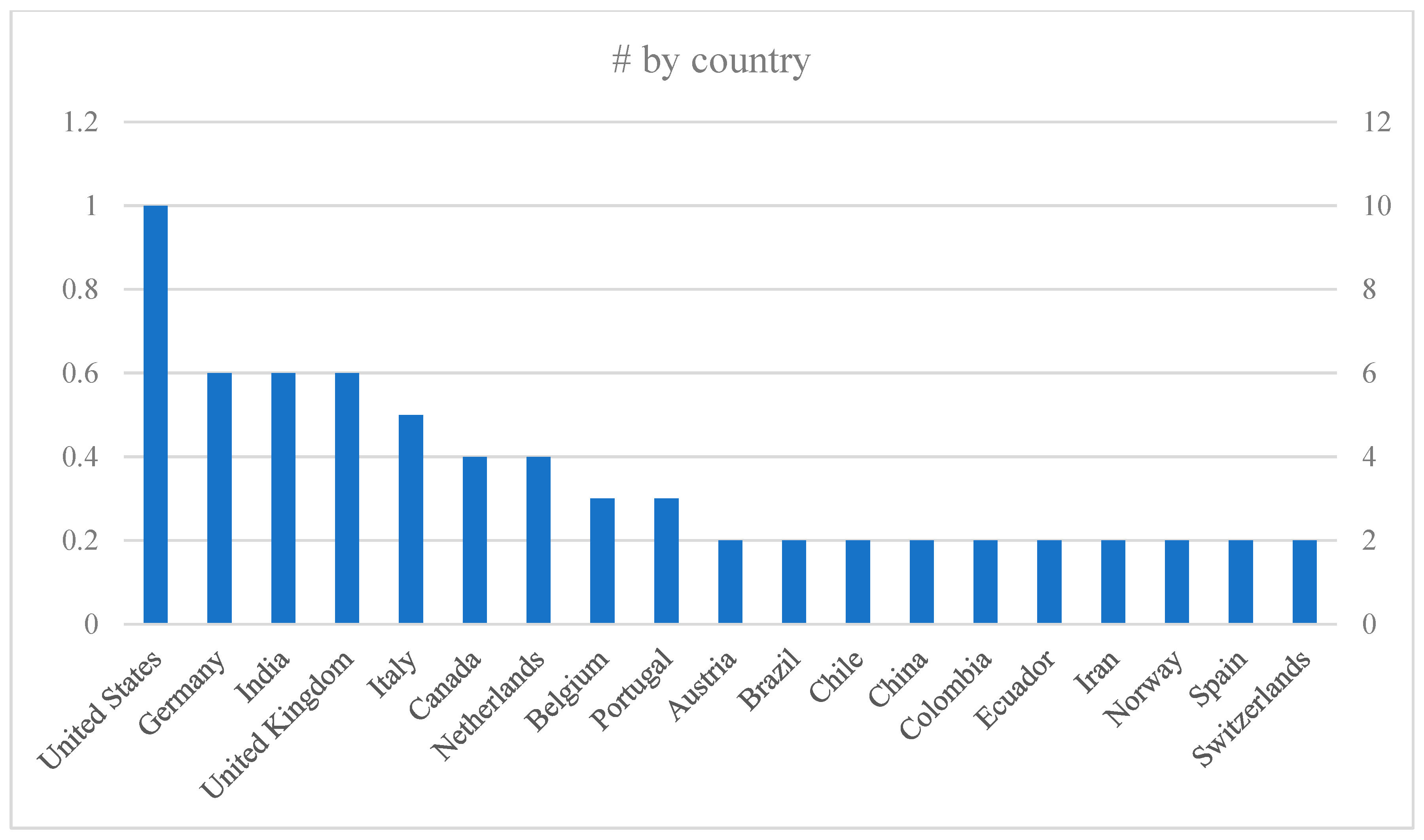

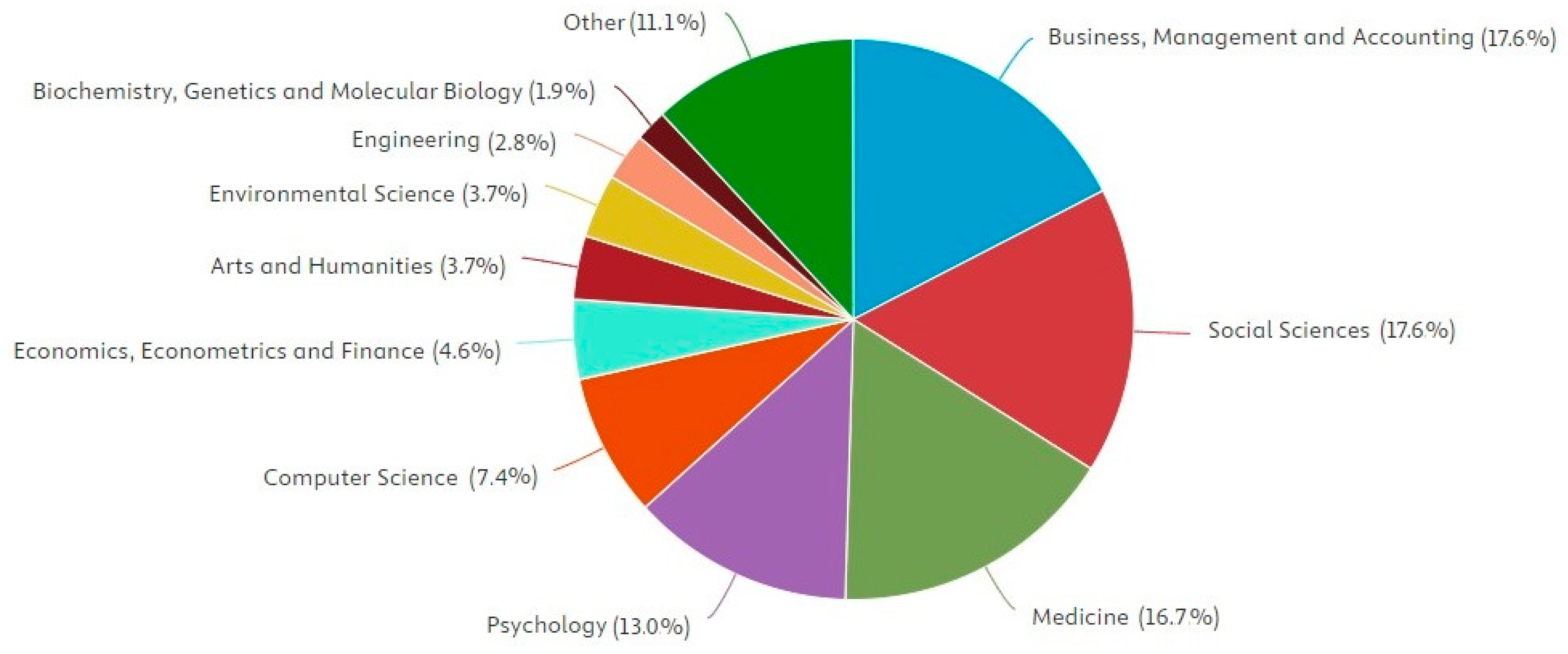

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Topic Clusters

3.2.1. Cluster 1—Mental Health and Job Performance

3.2.2. Cluster 2—COVID-19 and Impact on Work

3.2.3. Cluster 3—Professional Stress and Work Engagement

3.2.4. Cluster 4—Well-Being, Social Relationships, and Social Support in Remote Work

3.2.5. Cluster 5—Working Conditions and Professional Isolation

3.2.6. Cluster 6—Productivity and Sustainability in Teleworking

3.3. Main Theories

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Research Lines

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palmucci, D.N.; Santoro, G. Managing employees’ needs and well-being in the post-COVID-19 era. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 4138–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, C.; Zi, Y. Teleworkability and its heterogeneity in labor market shock. J. Asian Eco. 2024, 92, 101741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurombe, M.D.; Rayners, S.S.; Mokgobu, K.A.; Manka, K. The perceived influence of remote working on specific human resource management outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 20, a2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Birkett, H.; Forbes, S.; Seo, H. COVID-19, flexible working, and implications for gender equality in the United Kingdom. Gend. Soc. 2021, 35, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, E.; Ribeiro, C.; Pereira, P.; Passos, C. Teletrabalho: Contributos e desafios para as organizações. Rev. Psicol. Organ. Trab. 2021, 21, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Teodoro, M.; Mento, C.; Giambò, F.; Vitello, C.; Italia, S.; Fenga, C. Work performance, mood and sleep alterations in home office workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerich, J. Prepared for home-based telework? The relation between telework experience and successful workplace arrangements for home-based telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahriar, S.H.B.; Alam, M.S.; Arafat, S.; Khan, M.R.; Nur, J.M.E.H.; Khan, S.I. Remote work and changes in organizational HR practices during Corona pandemic: A study from Bangladesh. Vision 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, V.; Ramos-Galarza, C.; Tejera, E. Teletrabajo en tiempos de COVID-19. Inter. J. Phys. 2020, 54, e1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobia, L.; Vittorini, P.; Di Battista, G.; D’Onofrio, S.; Mastrangeli, G.; Di Benedetto, P.; Fabiani, L. Study on psychological stress perceived among employees in an Italian University during mandatory and voluntary remote working during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K.; Kumar, B.D.; Singh, N.; Kumari, P.; Ranjan, M.; Verma, A. The impact of COVID-19-induced factors on “work from home” of employees. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2021, 13, S1000–S1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulrahim, H.; Yousif, G. Remote work implications on productivity of workers in the Saudi financial sector. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, e01064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.E.; Kurland, N.B. A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.A. Evolutionary roots of occupational burnout: Social rank and belonging. Adapt. Hum. Behav. Physiol. 2024, 10, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čopková, R. The relationship between burnout syndrome and boreout syndrome of secondary school teachers during COVID-19. J. Pedagog. Res. 2021, 5, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totseva, Y.; Bakracheva, M. Burnout, Borout and mobbing among teachers post COVID-19 restrictions. Psychol. Thought 2023, 16, 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.E.; Brooks, S.K.; Greenberg, N.; Weston, D. UK Government COVID-19 response employees’ perceptions of working from home: Content analysis of open-ended survey questions. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 66, e661–e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moens, E.; Lippens, L.; Sterkens, P.; Weytjens, J.; Baert, S. The COVID-19 crisis and telework: A research survey on experiences, expectations and hopes. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 729–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, D.M.; Januario, L.B.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Heiden, M.; Svensson, S.; Bergström, G. Working from home during the COVID-19 outbreak in Sweden: Effects on 24-h time-use in office workers. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedón, A.; Pujol, F.A.; Ramírez, T.; Mora, H.; Pujol, M. The importance of teleworking and its implications for Industry 5.0: A case study. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 80531–80547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, T.D. The role of relationships in understanding telecommuter satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, M.N. Loss of work-life balance, experience of stress and anxiety among professionals working from home—An explortory study in a western Indian city. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health 2024, 14, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senerat, A.M.; Pope, Z.C.; Rydell, S.A.; Mullan, A.F.; Roger, V.L.; Pereira, M.A. Psychosocial and behavioral outcomes in the adult workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A 1-Year longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcelik, H.; Barsade, S.G. No employee an island: Workplace loneliness and job performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2018, 61, 2343–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, S. Strengths and weaknesses of remote work: A review of the literature. Issues Inf. Syst. 2023, 24, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyzwinski, L.-N. Organizational and occupational health issues with working remotely during the pandemic: A scoping review of remote work and health. J. Occup. Health 2024, 66, uiae005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficapal-Cusí, P.; Torrent-Sellens, J.; Palos-Sanchez, P.; González-González, I. The telework performance dilemma: Exploring the role of trust, social isolation and fatigue. Int. J. Manpow. 2024, 45, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraus, S.; Breier, M.; Dasí-Rodríguez, S. The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2020, 16, 1023–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2015, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual: Manual for VOSviewer Version 1.6.17; Universiteit Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, J.; Gschwind, L. Three generations of telework. New ICTs and the ®evolution from home office to virtual office. New Technol. Work. Employ. 2016, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, J.M. Making telecommuting happen. In A Guide for Telemanagers and Telecommuters; Van Nostrand: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, F.; Zappalà, S. Social isolation and stress as predictors of productivity perception and remote work satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of concern about the virus in a moderated double mediation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How Effective Is Telecommuting? Assessing the Status of Our Scientific Findings. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2015, 16, 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanti, T.; Guidetti, G.; Mazzei, E.; Zappalà, S.; Toscano, F. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e426–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F. Managing a virtual workplace. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2000, 14, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniscuaski, F.; Kmetzsch, L.; Soletti, R.C.; Reichert, F.; Zandonà, E.; Ludwig, Z.M.C.; Lima, E.F.; Neumann, A.; Schwartz, I.V.D.; Mello-Carpes, P.B.; et al. Gender, race and parenthood impact academic productivity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: From survey to action. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 663252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hare, D.; Gaughran, F.; Stewart, R.; Pinto da Costa, M. A cross-sectional investigation on remote working, loneliness, workplace isolation, well-being and perceived social support in healthcare workers. BJPsych Open 2024, 10, e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemțeanu, M.-S.; Dabija, D.-C. Negative impact of telework, job insecurity, and work–life conflict on employee behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodzic, S.; Prem, R.; Nielson, C.; Kubicek, B. When telework is a burden rather than a perk: The roles of knowledge sharing and supervisor social support in mitigating adverse effects of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl. Psychol. 2024, 73, 599–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, M.; Lindermayer, T.; Schuster, K.; Zhang, J.; von Terzi, P. Addressing loneliness in the workplace through human-robot interaction: Development and evaluation of a social office robot concept. i-com 2023, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Crawford, L.E.; Ernst, J.M.; Burleson, M.H.; Kowalewski, R.B.; Malarkey, W.B.; Van Cauter, E.; Berntson, G.G. Loneliness and health: Potential mechanisms. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelsen, S.N.; Vatne, S.-H.; Mikalef, P.; Choudrie, J. Digital working during the COVID-19 pandemic: How task–technology fit improves work performance and lessens feelings of loneliness. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 36, 2063–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakman, J.; Kinsman, N.; Stuckey, R.; Graham, M.; Weale, V. A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: How do we optimise health? BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendran, R.S.; Ponnapalli, A.R.; Wang, C.; Anoop, A.A. A dual pathway model of remote work intensity: A meta-analysis of its simultaneous positive and negative effects. Pers. Psychol. 2024, 77, 1351–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.W.; Zacher, H. Working from home: When is it too much of a good thing? Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2024, 36, 9–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel-Meulenbroek, R.; Voulon, T.; Bergerfurt, L.; Arkesteijn, M.; Hoekstra, B.; Van der Schaal, P.J. Perceived health and productivity when working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2023, 76, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H. Factors influencing home-based telework in Hanoi (Vietnam) during and after the COVID-19 era. Transportation 2011, 48, 3207–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, M.T.; Anwar, I.; Khan, N.A.; Saleem, I. Work during COVID-19: Assessing the influence of job demands and resources on practical and psychological outcomes for employees. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2021, 13, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraghty, S.; Oliver, K.; Wang, C.C. Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic for midwifery and nursing academics. Br. J. Midwifery 2022, 30, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koričan Lajtman, M. Exploring context-related challenges and adaptive responses while working from home during COVID-19. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2023, 26, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Narang, D. Digital economy and work-from-home: The rise of home offices amidst the COVID-19 outbreak in India. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 14, 924–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbogen, E.B.; Lanier, M.D.; Griffin, S.C.; Blakey, S.M.; Gluff, J.A.; Wagner, H.R., II; Tsai, J. A national study of Zoom fatigue and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for future remote work. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2022, 25, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Signore, F.; Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Russo, V.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. Wellbeing costs of technology use during COVID-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, É. Les Incidences du télétravail sur le travailleur dans les domaines professionnel, familial et social. Le Trav. Hum. 2019, 82, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Ni, Y. Good tools are essential to do the job: A study of impact of digital competencies on innovative work behavior of Chinese remote work employees. Inf. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W.J.; Belkin, L.Y.; Tuskey, S.; Conroy, S.A. Surviving remotely: How job control and loneliness during a forced shift to remote work impacted employee work behaviors and well-being. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovic, M. How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? The roles of power distance, individualism, and beliefs about telework. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 62, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zürcher, A.; Galliker, S.; Jacobshagen, N.; Lüscher Mathieu, P.; Eller, A.; Elfering, A. Increased working from home in vocational counseling psychologists during COVID-19: Associated change in productivity and job satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 750127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöllner, K.; Sulíková, R. The relationship between teleworking and job satisfaction: A comprehensive review of the literature. J Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2021, 15, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhuang, W. Can teleworking improve workers’ job satisfaction? Exploring the roles of gender and emotional well-being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 1433–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhont, J.; Di Tella, M.; Dubois, L.; Aznar, M.; Petit, S.; Spałek, M.; Boldrini, L.; Franco, P.; Bertholet, J. Conducting research in Radiation Oncology remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic: Coping with isolation. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 24, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voll, K.; Pfnür, A. Is the success of working from home a matter of configuration?—A comparison between the USA and Germany using PLS-SEM. J. Corp. Real Estate 2024, 26, 82–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Astudillo, L.M.; Vargas-Díaz, B.; Molina, C.; Serrano-Malebrán, J.; Garzón-Lasso, F. Teleworking in times of a pandemic: An applied study of industrial companies. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1061529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez, M.; Moimaz, S.; Garbin, A.; Saliba, T. Impacto en la salud integral de profesionales del área de tecnología de la información que teletrabajan durante la COVID-19. Poblac. Salud Mesoam 2022, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Delanoeije, J.; Verbruggen, M. Biophilia in the home–workplace: Integrating dog caregiving and outdoor access to explain teleworkers’ daily physical activity, loneliness, and job performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2024, 29, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taskin, L.; Bridoux, F. Telework: A challenge to knowledge transfer in organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 2503–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutters, S.T. Modelling long-term COVID-19 impacts on the U.S. workforce of 2029. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaut, J.W.; Kelley, H.H. The Social Psychology of Groups; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.; Meckling, W. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiman, S. Agency research in managerial accounting: A second book. Account. Organ. Soc. 1990, 15, 341–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouakket, S.; Aboelmaged, M. Factors influencing green information technology adoption: A multi-level perspective in emerging economies context. Inf. Dev. 2021, 39, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive Load During Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdogan, B.; Bauer, T. Leader-member exchange theory. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Chien, C.J.; Shen, L.F. Teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic: A leader-member exchange perspective. Evid. Based HRM 2023, 11, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Mendes, A.; Almeida, D.; Rocha, Á. Digital remote work influencing public administration employees satisfaction in public health complex contexts. Comput. Sci. Inf. Syst. 2023, 20, 1569–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petscavage-Thomas, J.M.; Hardy, S.; Chetlen, A. Mitigation tactics discovered during COVID-19 with long-term report turnaround time and burnout reduction benefits. Acad. Radiol. 2022, 29, 1786–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, A.; Richter, S. Hybrid work—A reconceptualization and research agenda. i-com 2024, 23, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrendt, D.; Sándor, E.; Chédorge-Farnier, D.; Schulte-Brochterbeck, L. Quality of Life in the EU in 2024: Results from the Living and Working in the EU e-Survey; Eurofund: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eng, I.; Tjernberg, M.; Champoux-Larsson, M.F. Hybrid workers describe aspects that promote effectiveness, work engagement, work-life balance, and health. Cogent Psychol. 2024, 11, 2362535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Selection | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Database: Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (telework* OR “home office” OR “work from home” OR telecommuting OR “virtual work” OR “remote work”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (loneliness OR isolation OR solitude OR “social isolation”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (performance OR productivity OR “work performance” OR “organizational performance”) | |

| Document type | Quantitative studies | |

| Empirical studies | ||

| Case studies | Dissertations (Master and Doctorate) | |

| Qualitative studies with application of interviews or questionnaires | Conferences | |

| Literature review | Book chapters | |

| Systematic review | ||

| Language | English, Portuguese, French, and Spanish | |

| Publication year | From 1 January 2000 to December 2024 | |

| Subject | Telework, loneliness, isolation, performance, productivity | |

| Results | Motivation | |

| Recognition | ||

| Job satisfaction | ||

| Performance | ||

| Engagement | ||

| Productivity | ||

| Innovation | ||

| Creativity | ||

| Knowledge sharing | ||

| Feedback | ||

| Autonomy | ||

| Self-esteem | ||

| Safety | ||

| Reduction in emotional exhaustion | ||

| Professional valorization | ||

| Responsibility | ||

| Skills | ||

| Quality | ||

| Loneliness | ||

| Social isolation | ||

| Burnout | ||

| Boreout | ||

| Frustration | ||

| Fatigue | ||

| Workaholism | ||

| Boredom | ||

| Monotony | ||

| Stress | ||

| Injustice | ||

| Discouragement | ||

| Disinterest |

| Research Method | % | Sample | # of Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | 12.31 | University Workers | 2 |

| ICT Workers | 2 | ||

| General Workers | 4 | ||

| Quantitative | 73.84 | Academic Staff | 3 |

| ICT Workers | 4 | ||

| Public Workers | 2 | ||

| Industry Workers | 3 | ||

| Bank Workers | 2 | ||

| Healthcare Workers | 4 | ||

| General Workers | 26 | ||

| Government Workers | 3 | ||

| Enterprise Workers | 1 | ||

| Mixed-method | 1.53 | Healthcare Workers | 1 |

| Non-empirical | 12.31 | 8 |

| Journal | H-Index SJR | SJR 2023 | JIF 2023 | Total Citation 2023 | Quartile | Research Area | Country | Articles No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Radiology | 110 | 1.06 | 3.8 | 9023 | Q1 | Medicine | USA | 1 |

| Applied Psychology | 111 | 2.66 | 4.9 | 6045 | Q1 | Psychology | UK | 1 |

| Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration | 27 | 0.76 | 3.3 | 857 | Q1 | Business, Manag./Accounting | UK | 1 |

| Behaviour and Information Technology | 95 | 1.01 | 2.9 | 5519 | Q1 | Psychology/Social science | UK | 1 |

| BJPsych Open | 44 | 1.46 | 3.9 | 3144 | Q1 | Medicine/Psychiatry | UK | 1 |

| Clinical and Translational Radiation Oncology | 31 | 1 | 2.7 | 1801 | Q1 | Medicine | Ireland | 1 |

| Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking | 180 | 1.44 | N/A | N/A | Q1 | Psychology/Social Sciences/Medicine | USA | 1 |

| Empirical Software Engineering | 93 | 1.51 | 3.5 | 5093 | Q1 | Computer Science | Netherlands | 1 |

| European Journal of Health Economics | 67 | 1.08 | 3.1 | 3700 | Q1 | Economics/Medicine | Germany | 1 |

| Frontiers in Public Health | 101 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 38,788 | Q1 | Medicine | Switzerland | 1 |

| Geoforum | 141 | 1.34 | 3.4 | 11,407 | Q1 | Social Sciences | UK | 1 |

| Global Business and Organizational Excellence | 25 | 1.15 | N/A | N/A | Q1 | Business/Manag./Accounting | USA | 1 |

| Human Resource Development International | 61 | 1.47 | 3.8 | 1732 | Q1 | Business/Manag./Accounting | UK | 1 |

| Human Resource Development Quarterly | 78 | 1.22 | 4.0 | 1963 | Q1 | Business/Manag./Accounting | USA | 1 |

| IEEE Access | 242 | 0.96 | 3.4 | 244,906 | Q1 | Computer Science | USA | 1 |

| Information Technology and People | 76 | 1.24 | 4.9 | 3763 | Q1 | Computer Science/Social Sciences | UK | 1 |

| International Journal of Manpower | 73 | 1.25 | 4.6 | 3311 | Q1 | Business/Manag./Account. | UK | 1 |

| Journal of Occupational Health Psychology | 146 | 2.17 | 5.9 | 8538 | Q1 | Psychology/Medicine | USA | 1 |

| Journal of Sleep Research | 139 | 1.41 | 3.4 | 9541 | Q1 | UK | 1 | |

| Kybernetes | 53 | 0.57 | 2.5 | 3515 | Q1 | Computer Science/Social Sciences | UK | 1 |

| Mayo Clinic Proceedings | 214 | 1.78 | 7.2 | 20,223 | Q1 | Medicine | UK | 1 |

| Personnel Psychology | 167 | 3.76 | 4.7 | 10,066 | Q1 | Business/Manag./Account/Psychology | USA | 1 |

| PLoS ONE | 435 | 0.84 | 2.9 | 808,083 | Q1 | Multidisciplinary | USA | 1 |

| Psychological Science in the Public Interest | 60 | 9.89 | 18.2 | 2770 | Q1 | Psychology | USA | 1 |

| Sustainability | 169 | 0.67 | 3.3 | 229,272 | Q1 | Computer Sciences/Social Sciences | Switzerland | 1 |

| Total Number of Published Articles | Articles on Topic | Authors | Authors’ Metrics | Affiliation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-Index | Citations | ||||

| 31 | 2 | Toscano, F. | 12 | 1032 | Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, Italy |

| 57 | 2 | Zappalà, S. | 16 | 1466 | Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Italy |

| 54 | 1 | Aboelmaged, M. | 20 | 2377 | University of Sharjah, United Arab Emirates |

| 196 | 1 | Allen, T.D. | 71 | 21,689 | University of South Florida, USA |

| Cluster | Keywords | % Articles | Example of Article | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Mental health and job performance | Anxiety, Anguish, Depression, Job performance, Psychological suffering, Loneliness, Mental stress | 26.2% | Gore, M.N. (2024). Loss of work–life balance, experience of stress and anxiety among professionals working from home—an exploratory study in a Western Indian city. | [24] |

| 2. COVID-19 and impact on work | COVID-19, Telework, Professional burnout, Family conflict, Prevention and control, Technostress | 18.1% | Tobia, L., Vittorini, P., Di Battista, G., D’Onofrio, S., Mastrangeli, G., Di Benedetto, P., & Fabiani L. (2024). Study on psychological stress perceived among employees in an Italian university during mandatory and voluntary remote working during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. | [10] |

| 3. Professional stress and work engagement | Professional stress, Psychology, Social isolation, Motivation, Work engagement | 16.4% | Galanti, T., Guidetti, G., Mazzei, E., Zappalà, S., & Toscano, F. (2021). Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: the impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. | [38] |

| 4. Well-being, social relationships, and social support in remote work | Emotional stress, Psychological well-being, Social interaction, Social support, Isolation in the workplace, Telework | 14.3% | O’Hare, D., Gaughran, F., Stewart, R., & Pinto da Costa, M. (2024). A cross-sectional investigation on remote working, loneliness, workplace isolation, well-being, and perceived social support in healthcare workers. | [41] |

| 5. Working conditions and professional isolation | Professional isolation, Occupational health, Telework, Working conditions, Turnover intentions | 13.8% | Nemțeanu, M.-S., & Dabija, D.-C. (2023). Negative impact of telework, job insecurity, and work–life conflict on employee behavior. | [42] |

| 6. Productivity and sustainability in teleworking | Productivity, Innovation, Knowledge sharing, Sustainability | 11.2% | Hodzic, S., Prem, R., Nielson, C., & Kubicek, B. (2024). When telework is a burden rather than a perk. The roles of knowledge sharing and supervisor social support in mitigating adverse effects of telework during the COVID-19 pandemic. | [43] |

| No | Theory | Articles Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maslow’s Theory of Need (also known as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory) [74]—It helps to understand that satisfying human needs is not limited to work itself, but also to the social interactions and emotional support that the workplace provides. Thus, this theory helps to identify the areas that need intervention to reduce the impact of loneliness and isolation in teleworking. | [55] |

| 5 | Self-Determination Theory [75]—This theory focuses on 3 basic psychological needs, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and allows us to explore how the workplace affects psychological needs and how these needs can, in turn, influence mental health, motivation, and performance in remote work. | [11,37,42,43,50] |

| 5 | Social Exchange Theory [76]—This suggests that social interactions in the workplace, such as feedback, social support, and recognition, influence workers’ well-being. | [20,37,41,42,50] |

| 1 | Agency Theory [77,78]—This analyzes the relationship between the principal (person who delegates the functions) and the agent (person who executes them), focusing on conflicts of interest that may arise due to the difference in objectives between both parties. This theory allows us to understand how the dynamics of supervision and communication in teleworking can affect a worker’s behavior. | [3] |

| 10 | Job Demands–Resources Model [63]—This highlights the need for a balance between work requests and available resources to improve the worker experience. | [12,36,38,48,49,52,59,60,64,68] |

| 1 | Compensatory Internet Use Theory [79]—This suggests that individuals use the internet as a resource that helps to meet emotional and social needs. | [80] |

| 1 | Cognitive Load Theory [81]—This argues that the mind has a limited capacity, and therefore, the amount of information to be processed must be optimized to facilitate learning. | [36] |

| 2 | Conservation of Resources Theory [82]—Individuals seek to protect and conserve their resources, aiming for well-being. According to this theory, stress arises when there is a threat or loss of these resources. | [42,48] |

| 1 | Leader–Member Exchange [83]—This explores the quality of the relationship between leader and “led”, suggesting that high-quality relationships can lead to better results at work. | [84] |

| Target | Recommendation | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| HR Managers | Implement structured virtual socialization (e.g., online coffee breaks, informal chat groups) | To reduce feelings of isolation and build team cohesion |

| Team Leaders | Provide training in emotional intelligence and remote team management/leadership | To identify early signs of distress and maintain engagement |

| Organizations (general) | Define and enforce clear boundaries between work and personal time | To minimize burnout and preserve work–life balance |

| Executives | Invest in digital well-being tools and mental health support (e.g., EAPs, access to therapists) | To promote psychological safety and resilience |

| IT & Facilities Teams | Assess and support ergonomic and technological conditions of employees’ home workspaces | To ensure equitable and productive working conditions |

| Policymakers | Update labor laws to address remote work-related risks (e.g., isolation, technostress) | To establish minimum standards for remote work environments and mental health protections |

| Industry Associations | Promote sector-specific best practices and guidelines for sustainable telework | To ensure competitive advantage while safeguarding employee well-being |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Figueiredo, E.; Margaça, C.; Sánchez-García, J.C. Loneliness and Isolation in the Era of Telework: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges for Organizational Success. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161943

Figueiredo E, Margaça C, Sánchez-García JC. Loneliness and Isolation in the Era of Telework: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges for Organizational Success. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161943

Chicago/Turabian StyleFigueiredo, Elisabeth, Clara Margaça, and José Carlos Sánchez-García. 2025. "Loneliness and Isolation in the Era of Telework: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges for Organizational Success" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161943

APA StyleFigueiredo, E., Margaça, C., & Sánchez-García, J. C. (2025). Loneliness and Isolation in the Era of Telework: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges for Organizational Success. Healthcare, 13(16), 1943. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13161943