“What You Leave…Will Leave You”: A Qualitative Study of Perceptions of Midwifery’s Intangible Heritage and Professional Identity Among Midwives and Student Midwives in Cyprus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Topic Guide

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

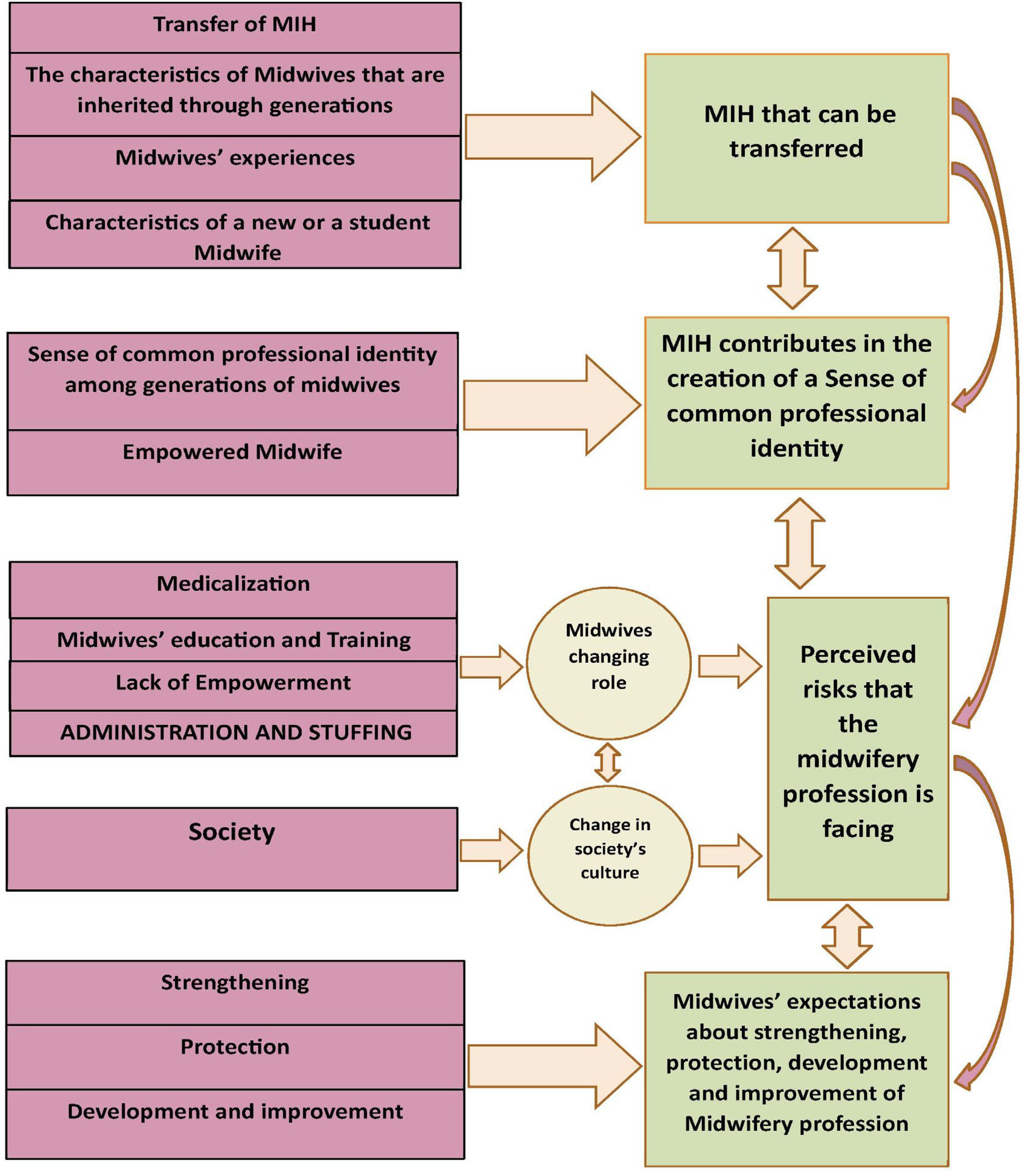

3. Results

3.1. Themes

3.1.1. The Elements That Constitute MIH and Their Transfer Through Generations

“… perpetuation of the species is a stable event in human life, and midwives are always needed” … “Society is changing but the MIH, such as being close to the woman, caressing her and talking to her does not change and no one can take it from the Midwife”.(M1)

Unless you see the old ones apply them and learn, you cannot have the adequate experience.(M6)

Oldest midwives should embrace the young ones. To be mentors.(M7)

[they] follow physicians’ orders and practice because they DON’T have experienced midwives to follow.(M4)

A midwife is a person of trust … to be trusted by women who asked for her during labour. I could not understand exactly how to create this trust, until I started my practice and then I felt that indeed during the time of delivery a woman is together with a midwife.(SM 4)

I believe that the most important thing is our independence. In other words, I learned from the old midwives how to be independent and empower myself. And when we, the youngest ones, also try… Yes, we want to take it further… And we will take it….(M 6)

3.1.2. The Sense of Common Professional Identity

We are thinking about the good of the mother and child and we put everything … aside … woman and child are coming always first.(SM 1)

What unites us all midwives like this, is that if you travel and go anywhere and find midwives, what unites us immediately… is the question if they have a lot of caesareans? What unites us is the concept that we all midwives believe in normal birth, and we are disturbed by the consequences of medicalization and deviations from normal birth and we fight to bring and keep birth in its normal state, as the old ones did… They wanted to give to the woman the choice to give birth naturally and we must keep it in this way. It characterizes midwives… it’s characteristic…(M1)

Midwives are different from other health professionals because they have to think, decide and act quickly. They can’t be late. You evaluate and decide immediately.(M2)

All midwives felt pride in saving a woman from an unnecessary caesarean section or an intervention.(M7)

There was a lady with her 20 years old son…she saw me and run towards me and hugged me…‘You delivered my son….i can never forget you’. Her son kneeled and kissed my hands. He said…‘these hands are the ones that touched me first…I honor them’…(Μ2)

She said to me…I will never forget your eyes, the way you stared at me and said… you will make it. And I believed you, and I made it. I will never forget that.(Μ2)

In the past, as students, we were left alone to do so many things, and experienced midwives were there if we needed them. By this way, we felt so strong. This strengthened us. We felt part of the team, the power of the maternity ward.(Μ14)

3.1.3. Perceived Risks That the Midwifery Profession Is Facing

I can remember that in older times a midwife was autonomous, strong, and independent and…alone. I was practicing alone at my village, and other midwives too… now, our issue is medicalization.(M3)

Reduction in normal births leads to a reduction of skills. So, this thing creates insecurities, creates a reduction in training for new midwives, a reduction in skills, a reduction in everything that is a vicious circle that will not stop.(M9)

The young midwives took from the old knowledge and experience. The increase in knowledge at the university level has reduced the practical part that will be useful to you in times of need. What you leave…will leave you.(M9)

During a night shift i was talking to a female patient, she was a teacher, about our role as midwives, that we do normal births …she was surprised…she thought we are just doctors’ assistants. And this is the majority’s opinion.(M9)

Because they know that they will be employed and paid by an obstetrician, and if they express a different opinion they will be fired.(M5)

They need to understand…first of all the administration of the hospital…If they cannot understand us…how do we expect to be understood by others.(M3)

First of all, we are understaffed and we can’t do our job. When there are two people working, how am I going to be next to a birthing woman and support her? I don’ t think that they understand what we are doing … we feel left out, we are alone. I’m not sure what’s going on in the end, but we’ve been side-lined.(M5)

3.1.4. Midwives’ Expectations About Their Profession

We need to reintroduce ourselves to society as midwives.(M10)

We have to show off our profession and what we are able to do.(SM4)

With antenatal classes we saw women change their perceptions. They started out telling me I will come [to the classes] but I am going to have a C/S, and after hearing about normal birth from us and from other women who had given birth, they became passionate about it. And that was the miracle of education.(M10)

[we need to] empower women through antenatal education so that they can demand their rights for normal birth.(M7)

We must go to schools and inform children about normal birth and breastfeeding, us midwives with experience in normal birth…what an investment for the future.(M1)

We have to investment in post-partum care. It is an area of maternity care where the midwife’s role has not been fully integrated or emphasized in the current system.(M13)

We have to go out to the community to regain our role and our autonomy back.(M10)

The experienced midwife should improve herself to pass on knowledge to and empower the new midwife. Be an example to follow.(M8)

An experienced midwife with evidenced based knowledge and skills is fundamental for student midwives.(SM1)

Full implementation of the Legislation is what we need.(SM3)

Midwives working in the private sector need empowerment, reinforcement and support to get ahead.(M2)

…empower women to assert their rights about normal birth and ask for a midwife to help them.(M1)

4. Discussion

4.1. Ethics

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CS | Caesarean section |

| MIH | Midwifery Intangible Heritage |

| M | Midwife |

| SM | Student midwife |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

References

- UNESCO. Intangible Cultural Heritage. What Is Intangible Cultural Heritage? 2013. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/en/%0Awhat-is-intangible-heritage-00003 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Decision 18.COM 8.b.26: Examination of Nominations for Inscription on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity—Midwifery: S and CO. 2023. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/Decisions/18.Cb.2.[.LHE-23-18 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Neary, S. Reclaiming professional identity through postgraduate professional development: Careers practitioners reclaiming their professional selves. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 2014, 42, 199–210. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03069885.2013.869790 (accessed on 10 June 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hadjigeorgiou, E. Midwifery in Cyprus: A Historical Overview. In Greek: H Μαιευτική Στην Κύπρο: Ιστορική Επισκόπηση, 1st ed.; Cyprus Nurses and Midwives Association: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2024; pp. 19–85. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, A.Χ. Midwifery in Cyprus-Yesterday-Today and Tomorrow. In Greek: H Μαιευτική Στην Κύπρο του Χθες του Σήμερα και του Aύριο; Cyprus Nursing Chronicles: Nicosia, Cyprus, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cylaw. Nursing and Midwifery Law 1988 (214/1988)—Consolitaed Law Text [In Greek: O Περι Νοσηλευτικής και Μαιευτικής Νόμος ενοποιημένος 2022]. Available online: https://www.cylaw.org/nomoi/indexes/1988_1_214.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- European Union. Directive 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications (Text with EEA relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2005, L255, 22–142. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2005/36/oj/eng (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Dawson, K.; Wallace, H.; Bayes, S. “I believe…”-graduating midwifery students’ midwifery philosophies and intentions for their graduate year: A longitudinal descriptive study. Midwifery 2023, 125, 103807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Confederation of Midwives. Essential Competencies for Midwifery Practice Framework 2019 Update; ICM: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://www.internationalmidwives.org/assets/files/general-files/2019/10/icm-competency-framework-2019-en-print.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Euro-Peristat Project. Core Indicators of the Health and Care of Pregnant Women and Babies in Europe in 2015. European Perinatal Health Report. 2018. Available online: www.europeristat.com (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Health MOF. Maternity Units of the Cyprus Government Controlled Areas Important Perinatal Health Indicators for the Years 2015–2021. 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.cy/media/sites/24/2024/05/Important-Perinatal-Health-Indicators-Cyprus-2015-2021.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Coxon, K. In Cyprus, “midwifery is dying.”. A qualitative exploration of midwives’ perceptions of their role as advocates for normal childbirth. Midwifery 2014, 30, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P. Data Analysis in qualitative resach: Thematic analysis [In Greek: Aνάλυση Δεδομένων Στην Ποιοτική Έρευνα Θεματική Aνάλυση]. Arch. Hell Med. Arch. Hell Med. 2018, 35, 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, N.; Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Kolokotroni, O.; Christodoulides, V.; Koliandri, I.; Nicolaou, C.; Papadopoulou, M.; Kouta, C.; Karanikola, M.; Baum, A.; et al. Identifying barriers to the educational role of midwives in Cyprus and defining determinants in behaviour terms using the Behaviour Change Wheel: A mixed-method formative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1233. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-08599-7 (accessed on 22 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kevern, J.; Webb, C. Focus groups as a tool for critical social research in nurse education. Nurse Educ. Today 2001, 21, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. Available online: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7 (accessed on 13 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1525822X05279903 (accessed on 13 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- McLafferty, I. Focus group interviews as a data collecting strategy. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 187–194. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03186.x (accessed on 16 April 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.13031 (accessed on 9 February 2023). [CrossRef]

- Papastavrou, E.; Andreou, P. Exploring sensitive nursing issues through focus group. Ealth. Sci. J. 2012, 6, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham, P.; Wilkinson, D. Using Research Instruments: A Toolkit for Researchers; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Luegmair, K.; Ayerle, G.M.; Steckelberg, A. Midwives’ action-guiding orientation while attending hospital births—A scoping review. Sex Reprod. Healthc. 2022, 34, 100778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, H.; Hines, H.F.; Labko, Y.; Peasley, A.; Valentin-Welch, M.; Breedlove, G. Midwives Mentoring Midwives: A Review of the Evidence and Best Practice Recommendations. J. Midwifery Womens Health 2022, 67, 21–30. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jmwh.13285 (accessed on 12 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijze, M.J.; Thompson, S.M.; Gudmundsdottir, E.Y.; Gottfreðsdóttir, H. Midwifery students’ perspectives on how role models contribute to becoming a midwife: A qualitative study. Women Birth 2020, 33, 433–439. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1871519219302100 (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewitt, M.; McEwan, T. Students stand at the door: Exploring views on professionalism in midwifery spaces. Br. J. Midwifery 2023, 31, 66–73. Available online: http://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/10.12968/bjom.2023.31.2.66 (accessed on 2 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hollins Martin, C.J.; MacArthur, J.; Martin, C.R.; McInnes, R.J. Midwives’ views of changing to a Continuity of Midwifery Care (CMC) model in Scotland: A baseline survey. Women Birth 2020, 33, e409–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, V.; Baird, K.; Fenwick, J. Nurturing autonomy in student midwives within a student led antenatal clinic. Women Birth 2020, 33, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, K.; Hastie, C.R.; Stanton, P.; Gamble, J. Learning to be a midwife: Midwifery students’ experiences of an extended placement within a midwifery group practice. Women Birth 2022, 35, e19–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiesmaello, M.; Kariman, N.; Sharif Nia, H.; Ozgoli, G.; Hajian, S.; Bazzazian, S.; Mokhtarian-Gilani, T. The translation and psychometric assessment of the perception of empowerment in midwifery scale: The Persian version. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 466. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-020-05326-y (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Larsson, M.; Aldegarmann, U.; Aarts, C. Professional role and identity in a changing society: Three paradoxes in Swedish midwives’ experiences. Midwifery 2009, 25, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, K. Midwifery:A profession in transition. Aust. J. Midwifery 2002, 15, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castejón, M.; Martínez-Alarcón, L.; Molina-Rodríguez, A.; Jiménez-Ruiz, I. Job Satisfaction Among Midwives in High-Intervention Birthing Rooms: A Qualitative Phenomenological Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendlove, Z. Risk and boundary work in contemporary maternity care: Tensions and consequences. Health Risk Soc. 2018, 20, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Belton, S.; Barclay, L.; Fenwick, J. Midwives in China: ‘jie sheng po’ to ‘zhu chan shi’. Midwifery 2009, 25, 203–212. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0266613807000332 (accessed on 6 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carolan, M.; Hodnett, E. ‘With woman’ philosophy: Examining the evidence, answering the questions. Nurs. Inq. 2007, 14, 140–152. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2007.00360.x (accessed on 15 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradfield, Z.; Hauck, Y.; Kelly, M.; Duggan, R. “It’s what midwifery is all about”: Western Australian midwives’ experiences of being ‘with woman’ during labour and birth in the known midwife model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 29. Available online: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-018-2144-z (accessed on 15 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galle, A.; Manaharlal, H.; Cumbane, E.; Picardo, J.; Griffin, S.; Osman, N.; Roelens, K.; Degomme, O. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in southern Mozambique: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 369. Available online: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-019-2532-z (accessed on 14 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- Vincifori, E.; Min, M.M. Ethical Code and Professional Identity: A Survey on Italian Midwives. Int. J. Childbirth 2014, 4, 55–62. Available online: http://connect.springerpub.com/lookup/doi/10.1891/2156-5287.4.1.55 (accessed on 14 June 2024). [CrossRef]

- WHO. Nursing and Midwifery Global Strategic Directions 2021–2025; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bradfield, Z.; Hauck, Y.; Duggan, R.; Kelly, M. Midwives’ perceptions of being ‘with woman’: A phenomenological study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 363. Available online: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-019-2548-4 (accessed on 10 February 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, R.; Hyde, R.; Llewelyn, F.; Shafiei, T.; Newton, M.; Forster, D.A. Factors associated with midwives’ job satisfaction and experience of work: A cross-sectional survey of midwives in a tertiary maternity hospital in Melbourne, Australia. Women Birth 2022, 35, e153–e162. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1871519221000482 (accessed on 22 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, K.; Lock, L.; Homer, C.S.E. Factors that contribute to midwives staying in midwifery: A study in one area health service in New South Wales, Australia. Midwifery 2011, 27, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leversidge, A. Why midwives leave-revisited. Midwives 2016, 19, 19. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30726601 (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Hildingsson, I.; Gamble, J.; Sidebotham, M.; Creedy, D.K.; Guilliland, K.; Dixon, L.; Pallant, J.; Fenwick, J. Midwifery empowerment: National surveys of midwives from Australia, New Zealand and Sweden. Midwifery 2016, 40, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomgren, J.; Gabrielsson, S.; Erlandsson, K.; Wagoro, M.C.; Namutebi, M.; Chimala, E.; Lindgren, H. Maternal health leaders’ perceptions of barriers to midwife-led care in Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Somalia, and Uganda. Midwifery 2023, 124, 103734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadée, F.; Perdok, H.; Sam, B.; de Geus, M.; Kweekel, L. “Twin2twin” an innovative method of empowering midwives to strengthen their professional midwifery organisations. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghini, F.K.; Iranifard, E.; Roudsari, R.L.; Najmabadi, K.M. The Role of Midwives in Women’s Empowerment: A Narrative Review. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 2023, 11, 3767–3781. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, V.; Nagle, C.; Yates, K.; McAuliffe, M.; Brown, L.; Byrne, M.; Waters, A. The role and scope of contemporary midwifery practice in Australia: A scoping review of the literature. Women Birth 2023, 36, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefford, E.; Jomeen, J.; Wallin, M. Midwifery Abdication—Is it acknowledged or discussed within the midwifery literature (Integrative Review)? Women Birth 2018, 31, S21. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1871519218304980 (accessed on 11 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Homer, C.S.; Friberg, I.K.; Dias, M.A.B.; ten Hoope-Bender, P.; Sandall, J.; Speciale, A.M.; Bartlett, L.A. The projected effect of scaling up midwifery. Lancet 2014, 384, 1146–1157. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S014067361460790X (accessed on 15 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- De-María, B.; Topa, G.; López-González, M.A. Cultural Competence Interventions in European Healthcare: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| List of Possible Questions (High Importance Questions, Questions that Provoke the Discussion) | |

|---|---|

| Experiences | 1. Talk to us about your experience as a midwife/student midwife about the way that MIH is transferred |

| 2. What was the element that helped you the most during the procedure of understanding midwifery practice and science? | |

| 3. Beyond university, what are your experiences in the clinical field and your contact with more “older” experienced midwives? a. If you wish, you can share with us specific incidents, events, experiences, anything that impressed you, etc. b. Do you believe that there is MIH that is passed through generations of midwives? | |

| Perceptions | 1. What gives midwives a “sense of professional identity”? Can you describe what it is that connects midwives–that creates a sense of common professional identity? |

| 2. What do you believe is the Cypriot Society’s view of the midwifery profession? 3. What do you understand by the concept of MIH? Do you think this is linked to the midwife′s sense of professional identity? 4. What are the elements that prepare a midwifery student/new midwife to practice the profession? | |

| Expectations | 1. Can you tell us in what ways the midwifery profession in Cyprus could be protected and developed (risks)? |

| 2. What could be the recommendations for improvement changes so that the profession of midwifery emerges again as an integral, elemental foundation of better perinatal care and a prosperous society? | |

| 3. Anything else you would like to add, which we did not cover above? Or that you have the chance to say? |

| Steps | Actions |

|---|---|

| 1 | Development of an introductory section for understanding the theme |

| 2 | Recording and transcribing |

| 3 | Dada coding |

| 4 | Making links with the literature |

| 5 | Grouping of similar codes and supporting interview extracts into categories |

| 6 | Codes and categories analysis: revision of codes, comparing differences and similarities, exchanging ideas and interpretations |

| 7 | Synthesis of categories into themes |

| 8 | Final agreement on the themes in relation to the literature and the available evidence |

| 9 | Selection of quotes illustrating the data analysis and the synthesis of the themes |

| Age | Status | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|

| 20–30 | 7 Nurses/student midwives | 1 year of experience in practicing midwifery as SM |

| 30–40 | 5 Midwives | 6–10 |

| 40–50 | 3 Midwives | 10–15 |

| 50–60 | 3 Midwives | 15–20 |

| Over 60 | 4 Midwives | Over 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panagiotou, M.; Hadjigeorgiou, E.; Vryonides, S.; Karanikola, M.; Merkouris, A.; Middleton, N. “What You Leave…Will Leave You”: A Qualitative Study of Perceptions of Midwifery’s Intangible Heritage and Professional Identity Among Midwives and Student Midwives in Cyprus. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151936

Panagiotou M, Hadjigeorgiou E, Vryonides S, Karanikola M, Merkouris A, Middleton N. “What You Leave…Will Leave You”: A Qualitative Study of Perceptions of Midwifery’s Intangible Heritage and Professional Identity Among Midwives and Student Midwives in Cyprus. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151936

Chicago/Turabian StylePanagiotou, Maria, Eleni Hadjigeorgiou, Stavros Vryonides, Maria Karanikola, Anastasios Merkouris, and Nicos Middleton. 2025. "“What You Leave…Will Leave You”: A Qualitative Study of Perceptions of Midwifery’s Intangible Heritage and Professional Identity Among Midwives and Student Midwives in Cyprus" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151936

APA StylePanagiotou, M., Hadjigeorgiou, E., Vryonides, S., Karanikola, M., Merkouris, A., & Middleton, N. (2025). “What You Leave…Will Leave You”: A Qualitative Study of Perceptions of Midwifery’s Intangible Heritage and Professional Identity Among Midwives and Student Midwives in Cyprus. Healthcare, 13(15), 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151936