Exploring Empowerment in Group Antenatal Care: Insights from an Insider and Outsider Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Context

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analyses

2.6. Reflexivity

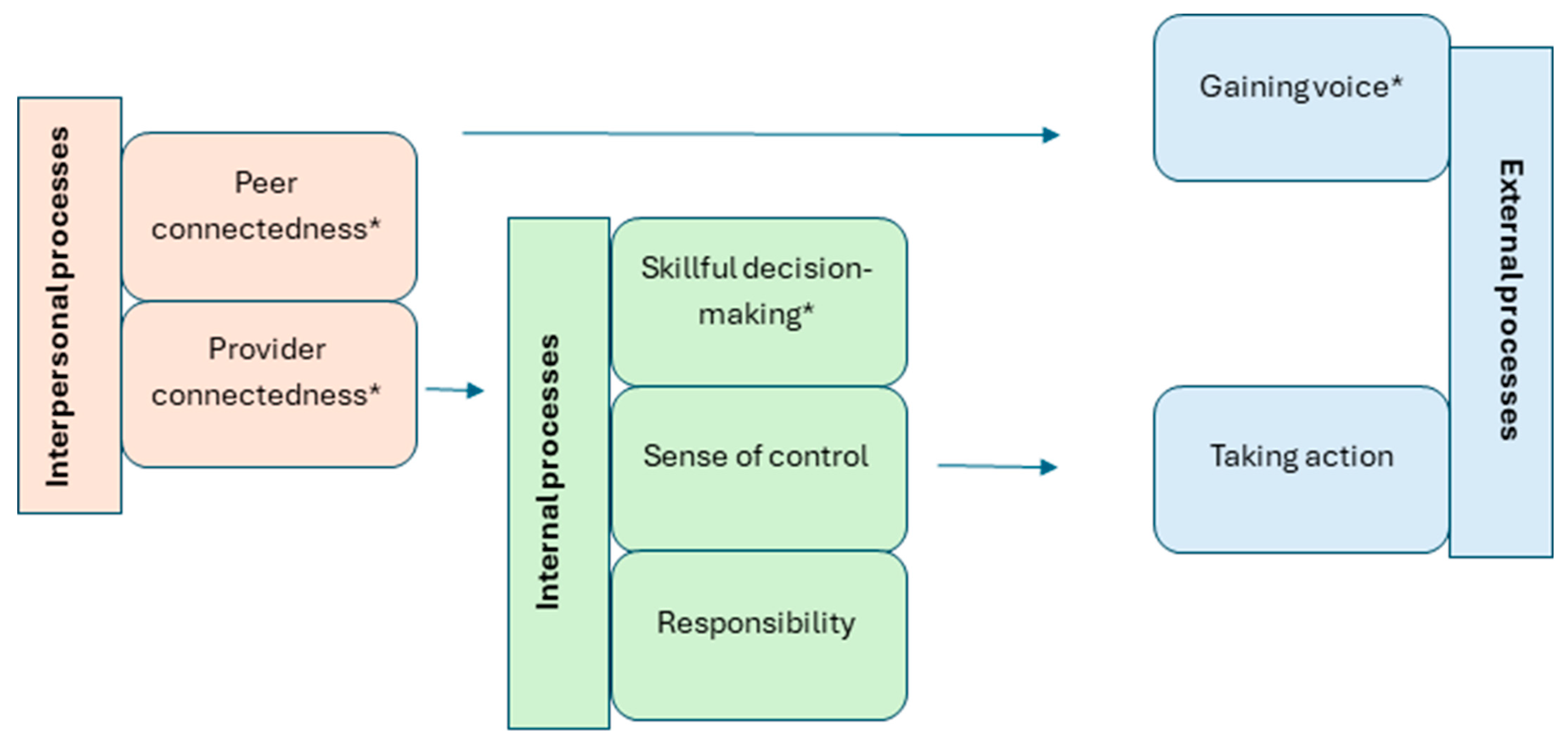

3. Results

3.1. General Findings

3.2. Interpersonal Processes

3.2.1. Theme 1: Peer Connectedness

3.2.2. Theme 2: Provider Connectedness

3.3. Internal Processes

3.3.1. Theme 3: Skillful Decision Making

3.3.2. Theme 4: Responsibility

3.3.3. Theme 5: Sense of Control

3.4. External Processes

3.4.1. Theme 6: Take Action

3.4.2. Theme 7: Gaining Voice

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GANC | Group Antenatal Care |

| PRES | Pregnancy-Related Empowerment Scale |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health 2016–2030; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 2471. [Google Scholar]

- Portela, A.; Santarelli, C. Empowerment of women, men, families and communities: True partners for improving maternal and newborn health. Br. Med. Bull. 2003, 67, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afulani, P.A.; Altman, M.; Musana, J.; Sudhinaraset, M. Conceptualizing pathways linking women’s empowerment and prematurity in developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.R.; Yim, I.S. A systematic review of concepts related to women’s empowerment in the perinatal period and their associations with perinatal depressive symptoms and premature birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Sahni, B.; Jena, P.K. Education, employment, economic status and empowerment: Implications for maternal health care services utilization in India. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, N.C.; Pratt, R.J.; Godecker, A.; Harrison, P.A.; Kim, H.; Kuendig, J.; O’Brien, J.M. Addressing perinatal depression in a group of underserved urban women: A focus group study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Finlayson, K.; Crossland, N.; Bonet, M.; Downe, S. What matters to women in the postnatal period: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leap, N. Woman-centred or women-centred care: Does it matter? Br. J. Midwifery 2009, 17, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.; Gibbons, K.S.; Bogossian, F. Defining woman-centred care: A concept analysis. Midwifery 2024, 131, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijze, M.; Leahy-Warren, P. Women’s empowerment in pregnancy and childbirth: A concept analysis. Midwifery 2019, 78, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.; Hauck, Y.L.; Crichton, C.; Barnes, C.; Poletti, C.; Overing, H.; Keyes, L.; Thomson, B. The perceptions and experiences of women who achieved and did not achieve a waterbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olza, I.; Leahy-Warren, P.; Benyamini, Y.; Kazmierczak, M.; Karlsdottir, S.I.; Spyridou, A.; Crespo-Mirasol, E.; Takács, L.; Hall, P.J.; Murphy, M. Women’s psychological experiences of physiological childbirth: A meta-synthesis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rising, S.S. Centering pregnancy: An interdisciplinary model of empowerment. J. Nurse-Midwifery 1998, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rising, S.S.; Kennedy, H.P.; Klima, C.S. Redesigning prenatal care through CenteringPregnancy. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2004, 49, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, E.B.; Barbier, K.; Sarabia, R.; Macones, G.A.; Cahill, A.G.; Tuuli, M.G. Group versus traditional prenatal care in low-risk women delivering at term: A retrospective cohort study. J. Perinatol. 2017, 37, 769–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellinger, M.M.; Abernathy, M.P.; Amerman, B.; May, C.; Foxlow, L.A.; Carter, A.L.; Barbour, K.; Luebbehusen, E.; Ayo, K.; Bastawros, D. Improved outcomes for Hispanic women with gestational diabetes using the Centering Pregnancy© group prenatal care model. Matern. Child Health J. 2017, 21, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubay, A.T.; Mansalis, K.A.; Simpson, M.J.; Armitage, N.H.; Briscoe, G.; Potts, V. The effects of group prenatal care on infant birthweight and maternal well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Mil. Med. 2019, 184, e440–e446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiku, F.; Bucinca, H.; Talrich, F.; Molliqaj, V.; Selmani, E.; McCourt, C.; Rijnders, M.; Little, G.; Goodman, D.C.; Rising, S.S. Maternal satisfaction with group care: A systematic review. AJOG Glob. Rep. 2024, 4, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, J.; Boned-Rico, L.; Olander, E.K.; McCourt, C. A systematic review of providers’ experiences of facilitating group antenatal care. Reprod. Health 2021, 18, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benahmed, N.; Lefevre, M.; Christiaens, W.; Devos, C.; Stordeur, S. Towards Integrated Antenatal Care for Low-Risk Pregnancy; Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Devlieger, R.; Goemaes, R.; Laubach, M. Perinatale Gezondheid in Vlaanderen, Jaar 2020; Perinatal Health in Flanders, Year 2020; Studiecentrum voor Perinatale Epidemiologie: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Malchi, F.; Abedi, P.; Iravani, M.; Maraghi, E.; Mohammadi, E.; Saadati, N. The effect of group prenatal care on the empowerment of pregnant adolescents: Randomised controlled trial. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2023, 23, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, C.L.; Klima, C.S.; Leshabari, S.C.; Steffen, A.D.; Pauls, H.; McGown, M.; Norr, K.F. Randomized controlled pilot of a group antenatal care model and the sociodemographic factors associated with pregnancy-related empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, L. Women’s perceived quality of care and self-reported empowerment with centeringpregnancy versus individual prenatal care. Nurs. Women’s Health 2019, 23, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, B.; Ouedraogo, Y.; Mhlanga, M.; Kone, A. Exploring the Acceptability and Impact of Group Antenatal Care: A Qualitative Study Among Women in Selected Health Facilities in Burkina Faso. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.; Da Motta, G.; McCourt, C.; Wiseman, O.; Rayment, J.; Haora, P.; Wiggins, M.; Harden, A. Better together: A qualitative exploration of women’s perceptions and experiences of group antenatal care. Women Birth 2019, 32, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, P.; Bangura, A.H.; Nirola, I.; Citrin, D.; Belbase, B.; Bogati, B.; Nirmala, B.; Khadka, S.; Kunwar, L.; Halliday, S. The power of peers: An effectiveness evaluation of a cluster-controlled trial of group antenatal care in rural Nepal. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehay, A.; Motta, G.D.; Hunter, L.; Rayment, J.; Wiggins, M.; Haora, P.; McCourt, C.; Harden, A. What are the mechanisms of effect of group antenatal care? A systematic realist review and synthesis of the literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caelli, K.; Ray, L.; Mill, J. ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2003, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Epistemological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiry. Ectj 1982, 30, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.; Birks, M. Qualitative Methodology: A Practical Guide; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, B.; Madill, A. Subjectivity in psychological science: From problem to prospect. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuli, K.; Decabooter, K.; Talrich, F.; Renders, A.; Beeckman, K. Born in Brussels screening tool: The development of a screening tool measuring antenatal psychosocial vulnerability. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S. Research design and methods: A systematic review of research paradigms, sampling issues and instruments development. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, S.J. Population research: Convenience sampling strategies. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2021, 36, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaDonna, K.A.; Artino Jr, A.R.; Balmer, D.F. Beyond the guise of saturation: Rigor and qualitative interview data. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2021, 13, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klima, C.S.; Vonderheid, S.C.; Norr, K.F.; Park, C.G. Development of the pregnancy-related empowerment scale. Nurs. Health 2015, 3, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy-Warren, P.; Nieuwenhuijze, M. Measuring women’s empowerment during the perinatal period in high income countries: A scoping review of instruments used. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. Freire re-viewed. Educ. Theory 2007, 57, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D.; Thomas, B. Nursing and the “F” word. In Nursing Forum; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of personal agency through the self-efficacy mechanism. In Self-Efficacy; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Supporting best practice in reflexive thematic analysis reporting in Palliative Medicine: A review of published research and introduction to the Reflexive Thematic Analysis Reporting Guidelines (RTARG). Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, D. A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1391–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.; Da Motta, G.; McCourt, C.; Wiseman, O.; Rayment, J.; Haora, P.; Wiggins, M.; Harden, A. It makes sense and it works’: Maternity care providers’ perspectives on the feasibility of a group antenatal care model (Pregnancy Circles). Midwifery 2018, 66, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kweekel, L.; Gerrits, T.; Rijnders, M.; Brown, P. The role of trust in centeringpregnancy: Building interpersonal trust relationships in group-based prenatal care in The Netherlands. Birth 2017, 44, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somji, A.; Ramsey, K.; Dryer, S.; Makokha, F.; Ambasa, C.; Aryeh, B.; Booth, K.; Xueref, S.; Moore, S.; Mwenesi, R. “Taking care of your pregnancy”: A mixed-methods study of group antenatal care in Kakamega County, Kenya. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 969. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, S.D.; Sword, W.; Eryuzlu, L.E.; Biringer, A.B. A qualitative descriptive study of the group prenatal care experience: Perceptions of women with low-risk pregnancies and their midwives. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wagijo, M.-a.; Crone, M.; Bruinsma-van Zwicht, B.; van Lith, J.; Billings, D.L.; Rijnders, M. Contributions of CenteringPregnancy to women’s health behaviours, health literacy, and health care use in the Netherlands. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 35, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibellini, J.; Muscat, D.M.; Kizirian, N.; Gordon, A. Effect of health literacy interventions on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review. Women Birth 2021, 34, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresh, A.; Abrams, E.T.; Chirwa, E.; Jere, D.L.; Chodzaza, E.; Chorwe-Sungani, G.; Kafulafula, U.; Kapito, E.; Patel, D.R.; Jeremiah, R.D. Experiential training workshops for group antenatal care in Malawi. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, A.; Talrich, F.; Crone, M.; Rijnders, M.; Patil, C.L.; Rising, S.S.; Abanga, J.; Billings, D.L.; Hindori-Mohangoo, A.D.; Hindori, M.P. Identifying anticipated challenges when implementing group care: Context-analyses across seven countries to develop an anticipated challenges framework. Midwifery 2024, 139, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Group Care Global. Where We Work. 2022. Available online: https://groupcare.global/where-we-work/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ahrne, M.; Byrskog, U.; Essén, B.; Andersson, E.; Small, R.; Schytt, E. Group antenatal care (gANC) for Somali-speaking women in Sweden–a process evaluation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniele, M.A.S. Male partner participation in maternity care and social support for childbearing women: A discussion paper. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2021, 376, 20200021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, N.; Crone, M.R.; Hindori-Mohangoo, A.; Hindori, M.; Reis, R.; Hoxha, I.S.; Abanga, J.; Matthews, S.; Berry, L.; van der Kleij, R.M. Group Care in the first 1000 days: Implementation and process evaluation of contextually adapted antenatal and postnatal group care targeting diverse vulnerable populations in high-, middle-and low-resource settings. Implement. Sci. Commun. 2022, 3, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gresh, A.; Wilson, D.; Fenick, A.; Patil, C.L.; Coker, T.; Rising, S.S.; Glass, N.; Platt, R. A conceptual framework for group well-child care: A tool to guide implementation, evaluation, and research. Matern. Child Health J. 2023, 27, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Provider connectedness: A healthcare relationship that minimizes the power differential between clients and providers. These relationships are created within an environment of respect and trust. Skillful decision-making: A process by which women come to evaluate and choose a direction that will impact their health. Peer connectedness: A bond between women that develops from the evolution of caring and supportive relationships. Gaining voice: The ability of women to be knowledgeable about their health and advocate for their healthcare options for themselves and their families. |

| Setting 1 | Setting 2 | Setting 3 | Setting 4 | Total/Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of organization (Primary/secondary care) | Community Health Center (Primary) | Community Health Center (Primary) | University hospital (Secondary) | Non-profit organization (attached to a hospital) | n/a |

| Regular prenatal care performed by | Midwives | Midwives | Mainly gynecologists | Midwives | n/a |

| GANC performed by | 2 midwives | 2 midwives | 2 midwives or 1 midwife and 1 psychologist | 2 midwives | n/a |

| Number of months/years of GANC experience at the beginning of observation | 3 years | 3 years | 3 months | 1 year | n/a |

| Target group for GANC | All pregnant people, but especially residents | All pregnant people, but especially residents | People facing psychosocial and/or socioeconomic challenges | Pregnant people with no social security and living in precarious conditions | n/a |

| Number of groups observed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Number of sessions observed | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 21 |

| # women interviewed | 2 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 13 |

| # interviewed and participants in an observed group | 0 | 2 | 3 | n/a | 5 |

| Primiparous/multiparous | 1/1 | 2/0 | 5/4 | n/a | 8/5 |

| Mean age (range) | 28 (24–32) | 31 (27–35) | 30 (21–34) | n/a | 29.7 |

| # non-native Dutch or French speakers | 1 | 0 | 4 | n/a | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Talrich, F.; Van Damme, A.; Rijnders, M.; Bastiaens, H.; Beeckman, K. Exploring Empowerment in Group Antenatal Care: Insights from an Insider and Outsider Perspective. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151930

Talrich F, Van Damme A, Rijnders M, Bastiaens H, Beeckman K. Exploring Empowerment in Group Antenatal Care: Insights from an Insider and Outsider Perspective. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151930

Chicago/Turabian StyleTalrich, Florence, Astrid Van Damme, Marlies Rijnders, Hilde Bastiaens, and Katrien Beeckman. 2025. "Exploring Empowerment in Group Antenatal Care: Insights from an Insider and Outsider Perspective" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151930

APA StyleTalrich, F., Van Damme, A., Rijnders, M., Bastiaens, H., & Beeckman, K. (2025). Exploring Empowerment in Group Antenatal Care: Insights from an Insider and Outsider Perspective. Healthcare, 13(15), 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151930