Preoperative Suffering of Patients with Central Neuropathic Pain and Their Expectations Prior to Motor Cortex Stimulation: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. The Process of Interviewing

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

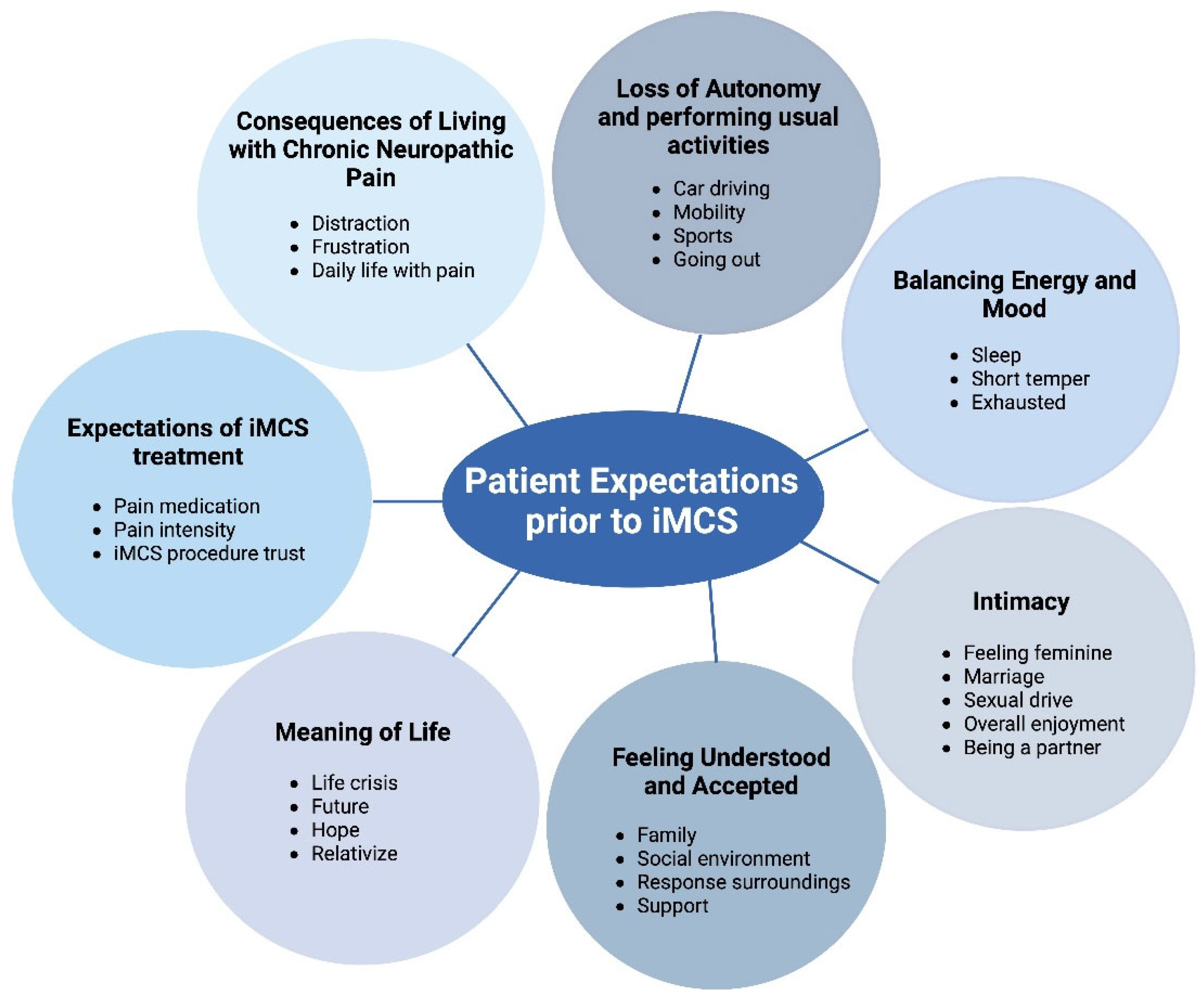

3.1. Themes Derived from the Interviews

3.2. The Consequence of Living with Chronic Neuropathic Pain

“I haven’t been able to get much sleep, which leaves me with little energy. And then the pain, it also affects my mood. That, in turn, has consequences for my social life and for my partner as well.”(Patient no. 7)

3.3. Loss of Autonomy and Performing Usual Activities

“I worked as a district nurse in a self-managing team, and there was always something to do. Then, I started working less and took on the scheduling. However, that soon became difficult as well, and I had to stop working because I was experiencing more and more side effects from medications. As a result, I lost my job, and now I’m on social benefits. I find that very challenging, and it makes me sad.”(Patient no. 15)

“On a better day, I do a little tidying around the house. I can manage dusting, but I can no longer vacuum. For that, I do have assistance.”(Patient no. 5)

3.4. Balancing Energy and Mood

“My husband does mention that I’ve changed. I become easily irritated and, yes, somewhat snappy, I suppose. There are times when I respond very curtly or with a touch of grumpiness. Whereas naturally, I’m a very calm person.”(Patient no. 1)

3.5. Intimacy

“I do not even want to think about him touching my cheek or kissing my lips. It would be excruciatingly painful.”(Patient no. 14)

3.6. Feeling Understood and Accepted

“Yes, there’s a lot of misunderstanding because it’s not visible. But if someone is interested, I’m willing to explain. However, I do expect them to remember and truly listen. The remarkable thing is that people whom you don’t know that well, or who happen to hear something about you and your pain, sometimes seem to understand it better and can also empathize more.”(Patient no. 9)

3.7. Meaning of Life

“I only keep going for my husband, my children and grandchildren. I really want to spend time with those little ones. That is one of the reasons why I want to try the iMCS treatment as well. If I did not have those people in my life, I would have stepped out earlier.”(Patient no. 3)

3.8. The Expectations of iMCS Treatment

“I hope that life will become more livable for me.”(Patient no. 13)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

4.4. Practice Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsubokawa, T.; Katayama, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Hirayama, T.; Koyama, S. Chronic motor cortex stimulation for the treatment of central pain. In Advances in Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery 9. Acta Neurochirurgica Supplementum; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1991; Volume 52, pp. 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubokawa, T.; Katayama, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Hirayama, T.; Koyama, S. Treatment of thalamic pain by chronic motor cortex stimulation. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1991, 14, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Tao, W.; Zhu, H.; Xiao, D.; Li, Y. The Effect of Motor Cortex Stimulation on Central Poststroke Pain in a Series of 16 Patients with a Mean Follow-Up of 28 Months. Neuromodulation 2017, 20, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt, E.; Henssen, D.; Steegers, M.; Staal, M.; Beese, U.; Maarrawi, J.; Pirotte, B.; Garcia-Larrea, L.; Rasche, D.; Vesper, J.; et al. Motor Cortex Stimulation in Patients Suffering from Chronic Neuropathic Pain: Summary of Expert Meeting and Premeeting Questionnaire, Combined with Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2017, 108, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodziej, M.A.; Hellwig, D.; Nimsky, C.; Benes, L. Treatment of Central Deafferentation and Trigeminal Neuropathic Pain by Motor Cortex Stimulation: Report of a Series of 20 Patients. J. Neurol. Surg. Part A Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 2016, 77, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyron, R.; Faillenot, I.; Mertens, P.; Laurent, B.; Garcia-Larrea, L. Motor cortex stimulation in neuropathic pain. Correlations between analgesic effect and hemodynamic changes in the brain. A PET study. Neuroimage 2007, 34, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, D.; Hamani, C.; Lozano, A. Efficacy and safety of motor cortex stimulation for chronic neuropathic pain: Critical review of the literature. J. Neurosurg. 2009, 110, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Fresnedo, A.; Perez-Vega, C.; Domingo, R.A.; Cheshire, W.P.; Middlebrooks, E.H.; Grewal, S.S. Motor Cortex Stimulation for Pain: A Narrative Review of Indications, Techniques, and Outcomes. Neuromodulation 2022, 25, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accardi-Ravid, M.; Eaton, L.; Meins, A.; Godfrey, D.; Gordon, D.; Lesnik, I.; Doorenbos, A. A qualitative descriptive study of patient experiences of pain before and after spine surgery. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, E.; Noordhof, R.K.; van Dongen, R.; Vissers, K.; Henssen, D.; Engels, Y. Spinal Cord Stimulation in Failed Back Surgery Syndrome: An Integrative Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies. Neuromodulation 2022, 25, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, D.J.; Tauben, D.J.; Sturgeon, J.A.; Godfrey, D.S.; Sullivan, M.D.; Doorenbos, A.Z. Treat the Patient, Not the Pain: Using a Multidimensional Assessment Tool to Facilitate Patient-Centered Chronic Pain Care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1235–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudman, L.; Smet, I.; Marien, P.; De Jaeger, M.; De Groote, S.; Huysmans, E.; Putman, K.; Van Buyten, J.P.; Buyl, R.; Moens, M. Is the Self-Reporting of Failed Back Surgery Syndrome Patients Treated with Spinal Cord Stimulation in Line With Objective Measurements? Neuromodulation 2018, 21, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M. Presurgical Psychological Assessments as Correlates of Effectiveness of Spinal Cord Stimulation for Chronic Pain Reduction COMMENTS. Neuromodulation 2016, 19, 422–428. [Google Scholar]

- Henssen, D.; Scheepers, N.; Kurt, E.; Arnts, I.; Steegers, M.; Vissers, K.; van Dongen, R.; Engels, Y. Patients’ Expectations on Spinal Cord Stimulation for Failed Back Surgery Syndrome: A Qualitative Exploration. Pain Pract. 2018, 18, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudman, L.; Moens, M. Moving Beyond a Pain Intensity Reporting: The Value of Goal Identification in Neuromodulation. Neuromodulation 2020, 23, 1057–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Premises, principles, and practices in qualitative research: Revisiting the foundations. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 976–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, S.C.; Pearl, R.G. Pain Management: Optimizing Patient Care Through Comprehensive, Interdisciplinary Models and Continuous Innovations. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2023, 41, xv–xvii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparkes, E.; Duarte, R.V.; Raphael, J.H.; Denny, E.; Ashford, R.L. Qualitative exploration of psychological factors associated with spinal cord stimulation outcome. Chronic. Illness 2012, 8, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, C.G.; Eldabe, S.; Chadwick, R.; Jones, S.E.; Elliott-Button, H.L.; Brookes, M.; Martin, D.J. An Exploration of the Experiences and Educational Needs of Patients with Failed Back Surgery Syndrome Receiving Spinal Cord Stimulation. Neuromodulation 2019, 22, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J.P.; Ménard-Lefaucheur, I.; Goujon, C.; Keravel, Y.; Nguyen, J.P. Predictive value of rTMS in the identification of responders to epidural motor cortex stimulation therapy for pain. J. Pain 2011, 12, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjesdal, K.; Dysvik, E.; Furnes, B. Living with chronic pain: Patients’ experiences with healthcare services in Norway. Nurs. Open 2018, 5, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudman, L.; Pilitsis, J.G.; Russo, M.; Slavin, K.V.; Hayek, S.M.; Billot, M.; Roulaud, M.; Rigoard, P.; Moens, M. From pain intensity to a holistic composite measure for spinal cord stimulation outcomes. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 131, e43–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkam, R.L.; Kurt, E.; van Dongen, R.; Arnts, I.; Steegers, M.A.H.; Vissers, K.C.P.; Henssen, D.J.H.A.; Engels, Y. Experiences From the Patient Perspective on Spinal Cord Stimulation for Failed Back Surgery Syndrome: A Qualitatively Driven Mixed Method Analysis. Neuromodulation 2021, 24, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarron, T.L.; MacKean, G.; Dowsett, L.E.; Saini, M.; Clement, F. Patients’ experience with and perspectives on neuromodulation for pain: A systematic review of the qualitative research literature. Pain 2020, 161, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, E.; Kollenburg, L.; Joosten, S.; van Dongen, R.; Engels, Y.; Henssen, D.; Vissers, K. Preoperative Counselling in Spinal Cord Stimulation: A Designated Driver in IPG-Related Inconveniences? Neuromodulation 2024, 27, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | Age | Pain Disorder | Side | Body Part | Duration of Pain (Years) | Mean Pain Intensity Prior to iMCS (NRS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 55 | Wallenberg syndrome | Right | Hemi-face | 4 | 8 |

| 2 | M | 61 | Post-stroke pain | Right | Upper extremity | 3 | 9 |

| 3 | F | 76 | Trigeminal neuropathic pain | Left | Hemi-face | 20 | 9 |

| 4 | F | 51 | Postherpetic trigeminal neuralgia | Left | Hemi-face | 4 | 9 |

| 5 | F | 62 | Post-stroke pain | Left | Hemi-face | 14 | 8 |

| 6 | F | 62 | Post-stroke pain | Left | Hemi-body | 6 | 8 |

| 7 | F | 52 | Post-stroke pain | Left | Upper extremity | 5 | 7 |

| 8 | M | 70 | Post-stroke pain | Right | Hemi-face | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | F | 59 | Secondary trigeminal neuralgia | Left | Hemi-face | 9 | 9 |

| 10 | F | 78 | Post-stroke pain | Right | Hemi-body | 3 | 8 |

| 11 | F | 72 | Wallenberg syndrome | Left | Hemi-face | 6 | 8 |

| 12 | F | 68 | Post-stroke pain | Right | Hemi-body | 3 | 8 |

| 13 | F | 69 | Post-stroke pain | Left | Upper extremity | 3 | 7 |

| 14 | M | 58 | Trigeminal neuropathic pain | Left | Hemi-face | 4 | 8 |

| 15 | M | 46 | Trigeminal neuropathic pain | Right | Hemi-face | 8 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurt, E.; Witkam, R.; van Dongen, R.; Vissers, K.; Engels, Y.; Henssen, D. Preoperative Suffering of Patients with Central Neuropathic Pain and Their Expectations Prior to Motor Cortex Stimulation: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151900

Kurt E, Witkam R, van Dongen R, Vissers K, Engels Y, Henssen D. Preoperative Suffering of Patients with Central Neuropathic Pain and Their Expectations Prior to Motor Cortex Stimulation: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151900

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurt, Erkan, Richard Witkam, Robert van Dongen, Kris Vissers, Yvonne Engels, and Dylan Henssen. 2025. "Preoperative Suffering of Patients with Central Neuropathic Pain and Their Expectations Prior to Motor Cortex Stimulation: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151900

APA StyleKurt, E., Witkam, R., van Dongen, R., Vissers, K., Engels, Y., & Henssen, D. (2025). Preoperative Suffering of Patients with Central Neuropathic Pain and Their Expectations Prior to Motor Cortex Stimulation: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(15), 1900. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151900