Application of AI Mind Mapping in Mental Health Care

Abstract

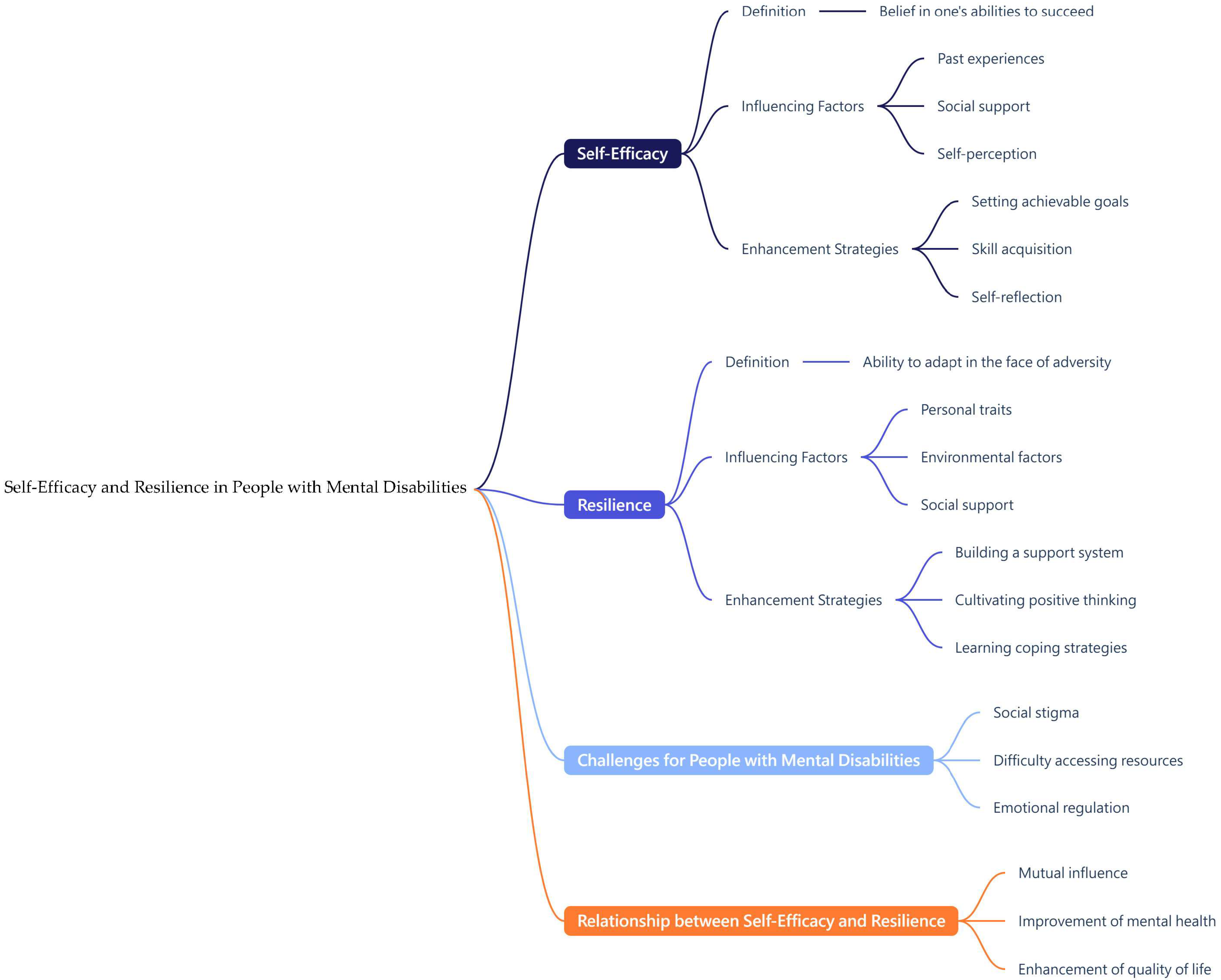

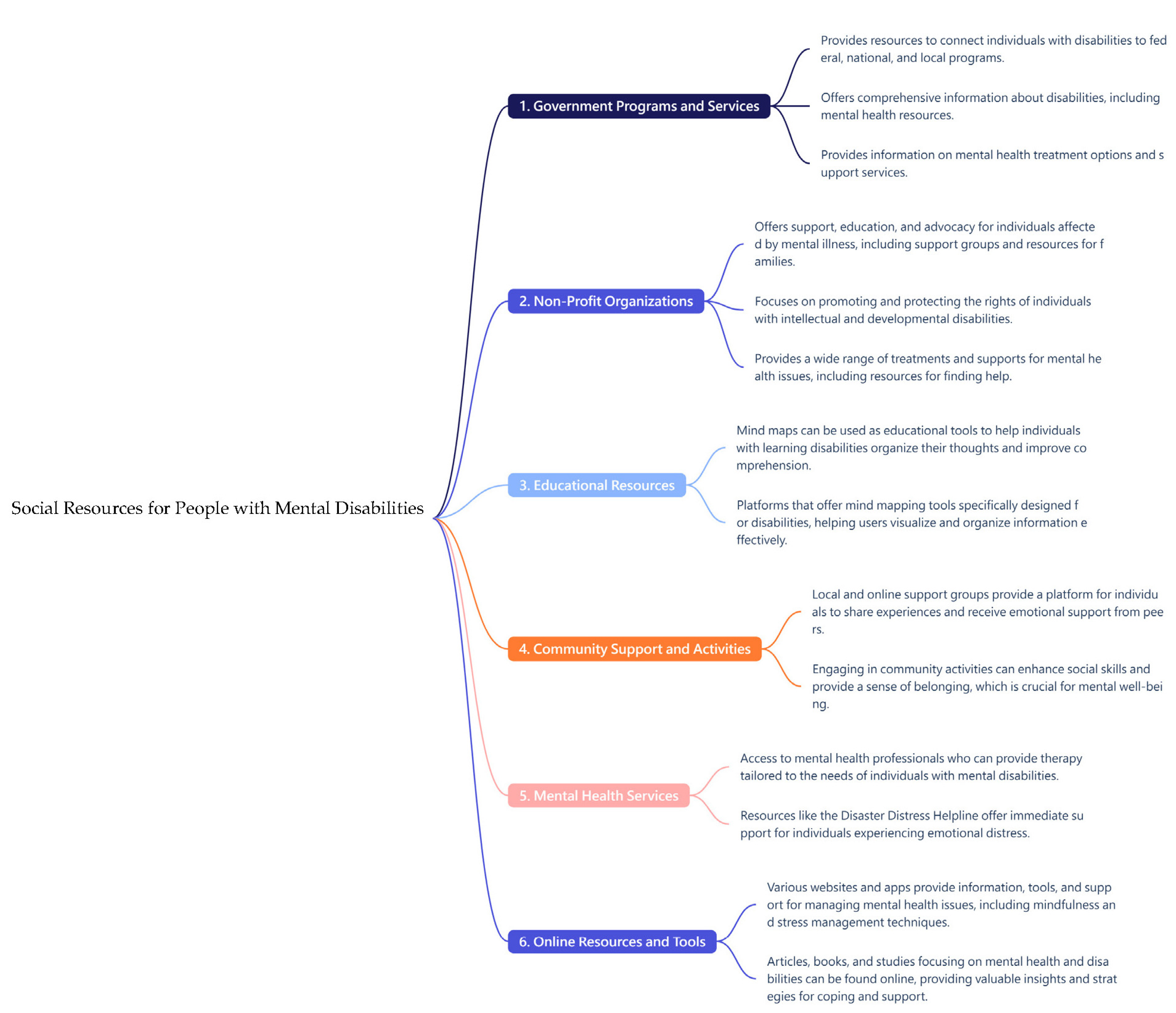

1. Introduction

- Improve information organization capabilities

- 2.

- Enhance memory and recall ability

- 3.

- Reduce anxiety and stress

- 4.

- Promote creativity and mental flexibility

- 5.

- Support collaboration and social interaction

- Visual thinking and learning

- 2.

- Automatic generation of mind maps

- 3.

- Enhancing participation and interactivity

- 4.

- Supporting multiple input formats

- 5.

- Improving learning efficiency

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Demographic Variable Questionnaire

2.2.2. Family Function Scale

2.2.3. Social Support Scale

2.2.4. Quality of Life Scale

2.2.5. Loneliness Scale

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.3.2. Inferential Statistics

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Sample Characteristics

3.2. Mediation Effect Analysis

3.2.1. Mediating Effect of Family Function, Social Support Satisfaction, and Quality of Life

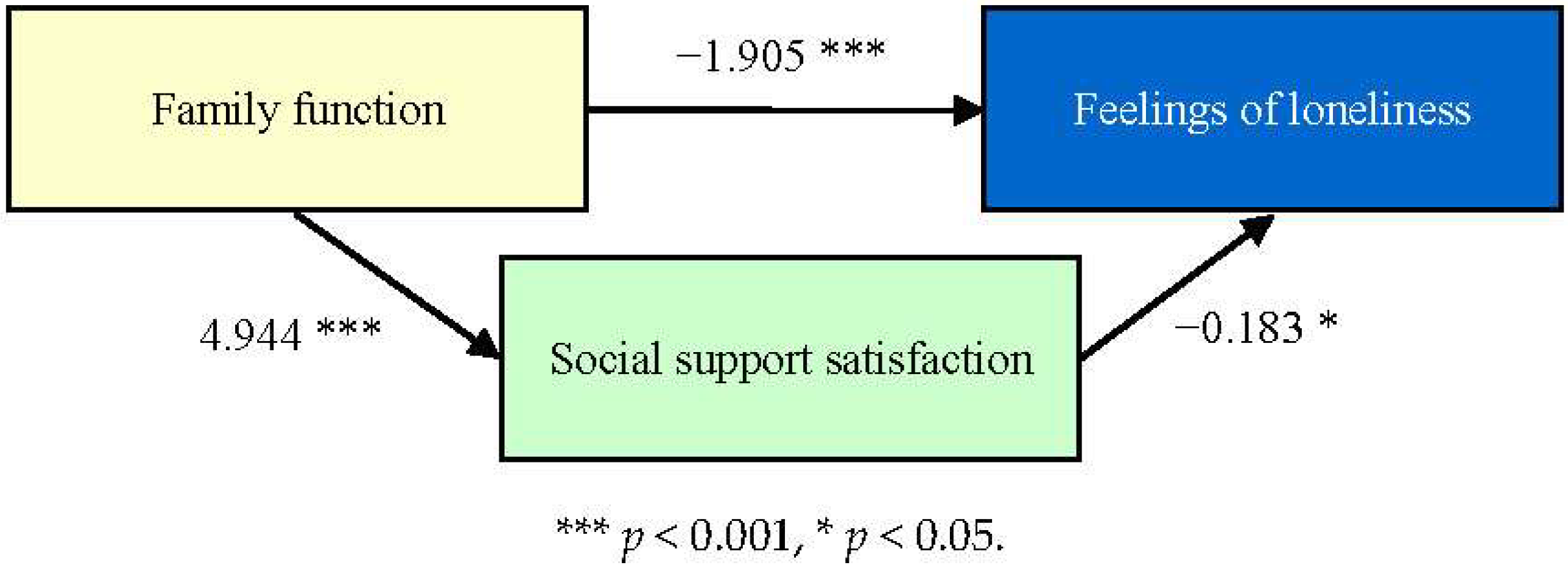

3.2.2. Mediating Effect of Family Function, Social Support Satisfaction, and Loneliness

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The World Health Report 2001—Mental health: New Understanding, New Hope. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/268478 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Smilkstein, G. The physician and family function assessment. Fam. Syst. Med. 1984, 2, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, N.S.; Jethwani, K.S. Understanding family functioning and social support in unremitting schizophrenia: A study in India. Indian J. Psychiatry 2010, 52, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Relationship Between Self-Stigma, Family Function and Disease Prognosis in Patients with Mental Illness. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/28pcjc (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Supportive Communication. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283326465_Supportive_communication (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Segrin, C.; Domschke, T. Social support, loneliness, recuperative processes, and their direct and indirect effects on health. Health Commun. 2011, 26, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supported Socialization for People with Psychiatric Disabilities: Lessons from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jcop.20013 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Mauricio, T. Handbook of Social Functioning in Schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorkle, B.H.; Rogers, E.S.; Dunn, E.C.; Lyass, A.; Wan, Y.M. Increasing social support for individuals with serious mental illness: Evaluating the compeer model of intentional friendship. Community Ment. Health J. 2008, 44, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beels, C.C. Social support and schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1981, 7, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Buchanan, J. Social support and schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 1995, 9, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayer-Anderson, C.; Morgan, C. Social networks, support and early psychosis: A systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2013, 22, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.C.; Kao, C.C. Quality of Life in Psychiatric Patients and Its Assessment. Taiwan Psychiatry 2005, 19, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Lu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.S.; Ng, C.H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Li, M.; Meng, X.; Xiang, Y.T. Quality of life in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of comparative studies. Psychiatr. Q. 2019, 90, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, D.; Girma, S.; Abdeta, T. Quality of life and its association with psychiatric symptoms and socio-demographic characteristics among people with schizophrenia: A hospital-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.Y.; Lee, Y.; Hsu, S.T.; Yen, C.F. Loneliness in patients with schizophrenia. Taiwan J. Psychiatry 2021, 35, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badcock, J.C.; Adery, L.H.; Park, S. Loneliness in psychosis: A practical review and critique for clinicians. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulford, D.; Mueser, K.T. The importance of understanding and addressing loneliness in psychotic disorders. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, D.; Hansson, L. The social networks of persons with severe mental illness in in-patient settings and supported community settings. J. Ment. Health 2002, 11, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, P.; Durbin, J.; Foster, R.; Boyles, S.; Babiak, T.; Lancee, B. Social networks of residents in supportive housing. Community Ment. Health J. 1992, 28, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R.W.; Rollins, A.L.; Lehman, A.F. Social network correlates among people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2003, 26, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, J.D.; Oyo, A.; Mora, O.; Wyka, K.; Schonebaum, A.D. Loneliness among persons with severe mental illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perese, E.F.; Wolf, M. Combating loneliness among persons with severe mental illness: Social network interventions’ characteristics, effectiveness, and applicability. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 26, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Mind Map Book. Available online: https://book.douban.com/subject/1463125/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Smilkstein, G.; Ashworth, C.; Montano, D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J. Fam. Pract. 1982, 15, 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.C. The Relationship between Internet Addiction, Social Support and Life Adjustment among University Students. Master’s Thesis, Tunghai University, Taichung, Taiwan, 2003. Available online: https://ndltd.ncl.edu.tw/cgi-bin/gs32/gsweb.cgi?o=dnclcdr&s=id=%22091THU00331009%22.&searchmode=basic (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Huang, L.J. Relationships among Undergraduate Students′ Self-esteem, Social Support and Conflict Coping Styles in Romantic Relationship. Master’s Thesis, National Taichung University of Education, Taichung, Taiwan, 2012. Available online: https://9lib.co/document/eqoreekq (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Yao, K.P. Introduction to the Concepts and Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life. Formos. J. Med. 2002, 6, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.M. Factors Associated the Quality of Life among a Group of Schizophrenic Patients: A Comparison of Psychiatric Home Care Nursing Users and Non-Users. Master’s Thesis, National Taipei University of Nursing and Health Sciences, Taipei, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Whoqol-Taiwan Group. Introduction to the Development of the WHOQOL- Taiwan Version. Chin. J. Public Health 2000, 19, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Cutrona, C.E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.C. A Study of the Relationship of Loneliness, Social Support and Happiness among College Students. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arnautovska, U.; Trott, M.; Vitangcol, K.J.; Milton, A.; Brown, E.; Warren, N.; Leucht, S.; Firth, J.; Siskind, D. Efficacy of User Self-Led and Human-Supported Digital Health Interventions for People with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2024, sbae143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.H.; Peng, M.M.; Bai, X.; Luo, W.; Yang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, B.; Thornicroft, G.; Chan, C.L.W.; Ran, M.S. Schizophrenia, social support, caregiving burden and household poverty in rural China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 1571–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Monshed, A.; Amr, M. Association between perceived social support and recovery among patients with schizophrenia. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 13, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240031029 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Hagos, D.H.; Battle, R.; Rawat, D.B. Recent Advances in Generative AI and Large Language Models: Current Status, Challenges, and Perspectives. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 5873–5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | β | SE | 95%C.I. | Bootstrap 95%C.I. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| Family function→Quality of life | 3.186 *** | 0.568 | 2.047 | 4.324 | 2.047 | 4.406 |

| Family function→Social support | 4.944 *** | 0.752 | 3.438 | 6.451 | 3.470 | 6.359 |

| Family function→Social support→Quality of life | 0.249 ** | 0.076 | 0.096 | 0.402 | 0.123 | 0.387 |

| Effect | SE | 95%C.I. | Bootstrap 95%C.I. | |||

| Total effect | 4.418 *** | 0.461 | 3.494 | 5.342 | ─ | ─ |

| Direct effect | ||||||

| Family function→Quality of life | 3.186 *** | 0.568 | 2.047 | 4.324 | ─ | ─ |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| Family function→Social support→Quality of life | 1.232 *** | 0.332 | ─ | ─ | 0.627 | 1.931 |

| Variables | β | SE | 95%C.I. | Bootstrap 95%C.I. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| Family function→Feelings of loneliness | −1.905 *** | 0.520 | −2.947 | −0.862 | −2.784 | −0.981 |

| Family function→Social support | 4.944 *** | 0.752 | 3.438 | 6.451 | 3.470 | 6.330 |

| Family function→Social support→Feelings of loneliness | −0.183 * | 0.070 | −0.323 | −0.043 | −0.302 | −0.071 |

| Effect | SE | 95%C.I. | Bootstrap 95%C.I. | |||

| Total effect | −2.811 *** | 0.409 | −3.632 | −1.991 | ─ | ─ |

| Direct effect | ||||||

| Family function→Feelings of loneliness | −1.905 *** | 0.520 | −2.947 | −0.862 | ─ | ─ |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| Family function→Social support→Feelings of loneliness | −0.906 ** | 0.313 | ─ | ─ | −1.571 | −0.337 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, H.-S.; Lee, B.-O.; Liu, C.-M. Application of AI Mind Mapping in Mental Health Care. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151885

Huang H-S, Lee B-O, Liu C-M. Application of AI Mind Mapping in Mental Health Care. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151885

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Hsin-Shu, Bih-O Lee, and Chin-Ming Liu. 2025. "Application of AI Mind Mapping in Mental Health Care" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151885

APA StyleHuang, H.-S., Lee, B.-O., & Liu, C.-M. (2025). Application of AI Mind Mapping in Mental Health Care. Healthcare, 13(15), 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151885