The Lack of Impact of Primary Care Units on Screening Services in Thailand and the Transition to Local Administrative Organization Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Population and Sampling

- Transferred between 2007 to 2012.

- Complete screening data.

- These criteria were used to ensure that the selected facilities had already undergone the transition period and made organizational adjustments following the transfer policy. Therefore, a total of 15 T-PCUs were selected.

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCU | Primary Care Unit |

| LAO | Local Administrative Organization |

| T-PCU | Transferred Primary Care Unit |

| NT-PCU | Non-Transferred Primary Care Unit |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| NHSO | National Health Security Office |

| GEE | Generalized Estimating Equations |

| CUP | Contracting Unit for Primary Care |

| VHV | Village Health Volunteer |

| UHC | Universal Health Coverage |

| MPH | Ministry of Public Health |

References

- Panda, B.; Thakur, H.P. Decentralization and health system performance—A focused review of dimensions, difficulties, and derivatives in India. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/258734 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- World Health Organization. Primary Health Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/primary-health-care (accessed on 17 June 2024).

- Sumriddetchkajorn, K.; Shimazaki, K.; Ono, T.; Kusaba, T.; Sato, K.; Kobayashi, N. Universal health coverage and primary care, Thailand. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Primary Health Care Systems (Primasys): Case Study from Thailand: Abridged Version. 2017. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/341041 (accessed on 17 July 2005).

- Tangcharoensathien, V.; Witthayapipopsakul, W.; Panichkriangkrai, W.; Patcharanarumol, W.; Mills, A. Health systems development in Thailand: A solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage. Lancet 2018, 391, 1205–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Rajatanavin, N.; Witthayapipopsakul, W.; Vongmongkol, V.; Saengruang, N.; Wanwong, Y.; Marshall, A.I.; Patcharanarumol, W.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Effective coverage of diabetes and hypertension: An analysis of Thailand’s national insurance database 2016–2019. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e066289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Hypertension. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/hypertension (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- International Diabetes Federation. Facts & Figures. Available online: https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/ (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Thanaviratananich, S.; Cho, S.-H.; Ghoshal, A.G.; Muttalif, A.R.B.A.; Lin, H.-C.; Pothirat, C.; Chuaychoo, B.; Aeumjaturapat, S.; Bagga, S.; Faruqi, R.; et al. Burden of respiratory disease in Thailand: Results from the APBORD observational study. Medicine 2016, 95, e4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, D.; Ford, N.; Unwin, N. Priorities for developing countries in the global response to non-communicable diseases. Glob. Health 2012, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaglehole, R.; Epping-Jordan, J.; Patel, V.; Chopra, M.; Ebrahim, S.; Kidd, M.; Haines, A. Improving the prevention and management of chronic disease in low-income and middle-income countries: A priority for primary health care. Lancet 2008, 372, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagaiya, N.; Phanthunane, P.; Bamrung, A.; Noree, T.; Kongweerakul, K. Forecasting imbalances of human resources for health in the Thailand health service system: Application of a health demand method. Hum. Resour. Health 2019, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Decentralization. Available online: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/international-health-systems-program/decentralization/ (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Hfocus.org. Summary of the Transfer of Missions from the Sub-District Hospital to the Provincial Administrative Organization. Available online: https://www.hfocus.org/content/2023/12/29374 (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Dougherty, S.; Lorenzoni, L.; Marino, A.; Murtin, F. The impact of decentralisation on the performance of health care systems: A non-linear relationship. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2022, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapkota, S.; Dhakal, A.; Rushton, S.; van Teijlingen, E.; Marahatta, S.B.; Balen, J.; Lee, A.C. The impact of decentralisation on health systems: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Glob Health 2023, 8, e013317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sriratanaban, J.; Singweratham, N.; Maneechay, M.; Komwong, D.; Pattarateerakun, N.; Sensai, S.; Siewchaisakul, P.; Watchareeboon, T.; Kaewpijit, U.; Saisum, B.; et al. Assessment of Population Health Impacts Subsequent to the Transfer of Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals (THPH) to the Provincial Administrative Organizations (PAOs) in the Fiscal Year2566: Phase 1 Warning Signs on Potential Health Impacts. 2023. Available online: https://kb.hsri.or.th/dspace/handle/11228/5951 (accessed on 31 December 2023).

- Jongudomsuk, P.; Srisasalux, J. A decade of health-care decentralization in Thailand: What lessons can be drawn? WHO South-East Asia J. Public Health 2012, 1, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singweratham, N.; Phodha, T.; Techakehakij, W.; Wongyai, D.; Bunpean, A.; Siewchaisakul, P. A Comparison on Budget Allocation of the National Health Security Fund between Contracting Unit for Primary Care and the Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals with and Without Transferred to the Local Administrative Organizations for Policy Recommendations. 2022. Available online: https://kb.hsri.or.th/dspace/handle/11228/5860 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Srisasalux, J.; Vichathai, C.; Kaewvichian, R. Experience with Health Decentralization: The Health Center Transfer Model. J. Health Syst. Res. 2009, 3, 16–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kulthanmanusorn, A.; Saengruang, N.; Wanwong, Y.; Kosiyaporn, H.; Witthayapipopsakul, W.; Srisasalux, J.; Putthasri, W.; Patcharanarumol, W. Evaluation of the Devolved Health Centers: Synthesis Lesson Learnt from 51 Health Centers and Policy Options. Available online: https://kb.hsri.or.th/dspace/handle/11228/4866 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Princess of Naradhiwas University. A Comparison of the Unit Costs of Health Care Services Provided with and Without Transfer to Local Administrative Organization of the Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals. 2023. Available online: https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/pnujr/article/view/258561 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Siewchaisakul, P.; Sarakarn, P.; Nanthanangkul, S.; Longkul, J.; Boonchieng, W.; Wungrath, J.; Gong, W. Role of literacy, fear and hesitancy on acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among village health volunteers in Thailand. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iamtrakul, P.; Chayphong, S. Factors affecting the development of a healthy city in Suburban areas, Thailand. J. Urban. Manag. 2023, 12, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, E.; Abimbola, S. The impact of decentralisation on health systems in fragile and post-conflict countries: A narrative synthesis of six case studies in the Indo-Pacific. Confl. Health 2023, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, S.A.; Bigdeli, M.; Langlois, E.V.; Riaz, A.; Orr, D.W.; Idrees, N.; Bump, J.B. Health systems changes after decentralisation: Progress, challenges and dynamics in Pakistan. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 30, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreeramareddy, C.T.; Sathyanarayana, T. Decentralised versus centralised governance of health services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD010830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T-PCU | NT-PCU | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population, Median (IQR) | 4521 (4549) | 4536 (3679) | 0.79 * |

| Size of PCU | |||

| Small | 3 | 12 | 0.91 ** |

| Medium | 10 | 27 | |

| Large * | 2 | 6 |

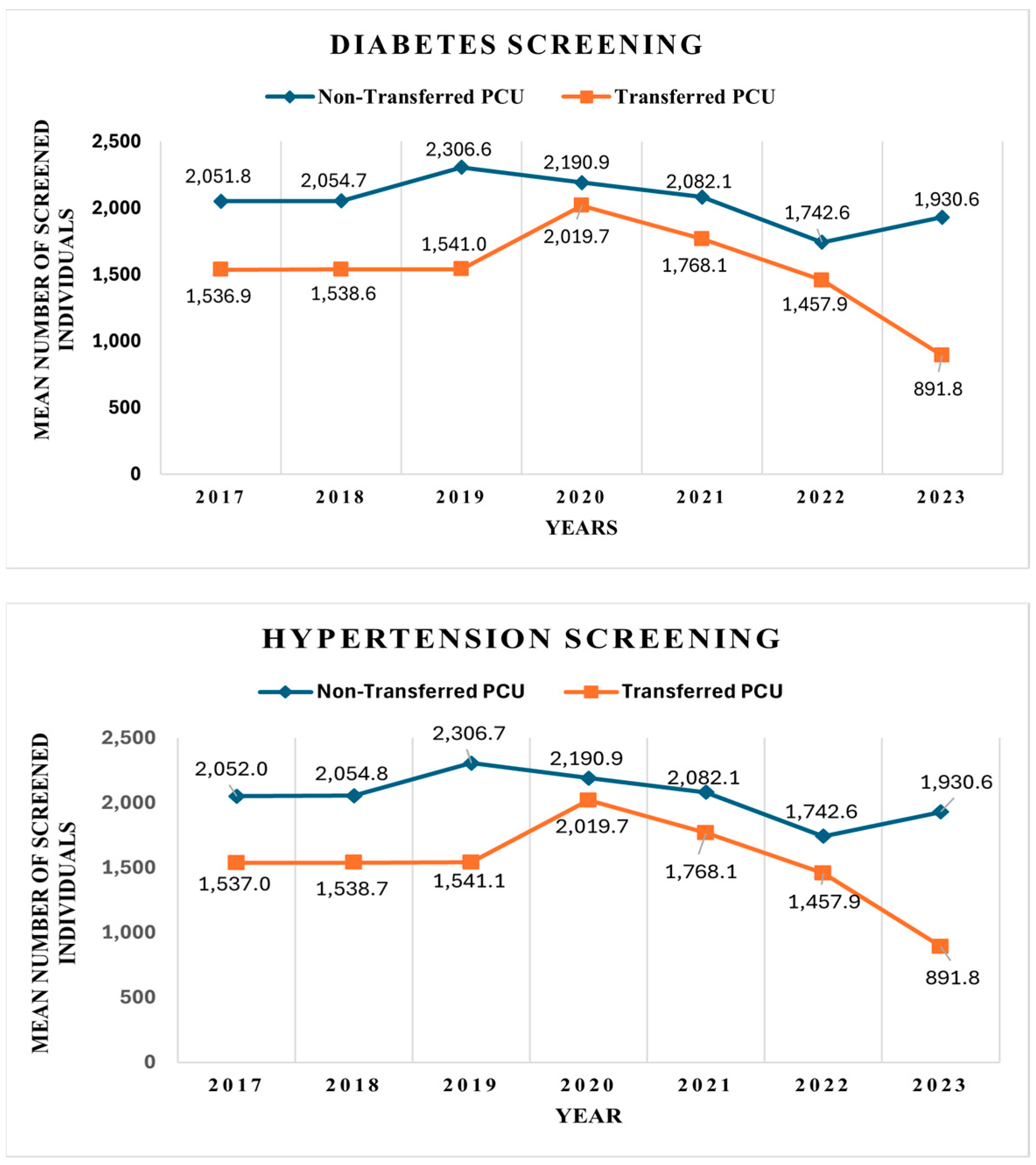

| Diabetes | Hypertension | ||||||

| Year | NT-PCU | T-PCU | NT-PCU vs. T-PCU | Year | NT-PCU | T-PCU | NT-PCU vs. T-PCU |

| 2017 | 2051.82 | 1536.9 | 514.92 | 2017 | 2052.0 | 1537.0 | 515.0 |

| 2018 | 2054.68 | 1538.63 | 516.05 | 2018 | 2054.8 | 1538.7 | 516.1 |

| 2019 | 2306.55 | 1540.97 | 765.58 | 2019 | 2306.7 | 1541.1 | 765.6 |

| 2020 | 2190.87 | 2019.73 | 171.14 | 2020 | 2190.9 | 2019.7 | 171.1 |

| 2021 | 2082.09 | 1768.13 | 313.96 | 2021 | 2082.1 | 1768.1 | 314.0 |

| 2022 | 1742.56 | 1457.93 | 284.63 | 2022 | 1742.6 | 1457.9 | 284.6 |

| 2023 | 1930.58 | 891.8 | 1038.78 | 2023 | 1930.6 | 891.8 | 1038.8 |

| Variables | Diabetes | p-Value | Hypertension | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AdjRR (95% CI) | AdjRR (95% CI) | |||

| T-PCU (vs NT-PCU) | 0.811 (0.468–1.403) | 0.453 | 0.814 (0.47–1.41) | 0.462 |

| Years | 0.978 (0.953–1.0) | 0.096 | 0.977 (0.951–1.01) | 0.100 |

| T-PCU ## Years | 0.972 (0.93–1.024) | 0.290 | 0.971 (0.922–1.023) | 0.278 |

| Variables | Screening | |

|---|---|---|

| AdjRR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Diabetes | ||

| T-PCU Years | 0.951 (0.900 to 1.005) | 0.076 |

| NT-PCU Years | 0.978 (0.955 to 1.002) | 0.074 |

| Hypertension | ||

| T-PCU Years | 0.950 (0.891 to 1.004) | 0.073 |

| NT-PCU Years | 0.977 (0.953 to 1.005) | 0.078 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singweratham, N.; Sriratanaban, J.; Komwong, D.; Maneechay, M.; Siewchaisakul, P. The Lack of Impact of Primary Care Units on Screening Services in Thailand and the Transition to Local Administrative Organization Policy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151884

Singweratham N, Sriratanaban J, Komwong D, Maneechay M, Siewchaisakul P. The Lack of Impact of Primary Care Units on Screening Services in Thailand and the Transition to Local Administrative Organization Policy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151884

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingweratham, Noppcha, Jiruth Sriratanaban, Daoroong Komwong, Mano Maneechay, and Pallop Siewchaisakul. 2025. "The Lack of Impact of Primary Care Units on Screening Services in Thailand and the Transition to Local Administrative Organization Policy" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151884

APA StyleSingweratham, N., Sriratanaban, J., Komwong, D., Maneechay, M., & Siewchaisakul, P. (2025). The Lack of Impact of Primary Care Units on Screening Services in Thailand and the Transition to Local Administrative Organization Policy. Healthcare, 13(15), 1884. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151884