Pharmacy Technicians in Immunization Services: Mapping Roles and Responsibilities Through a Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

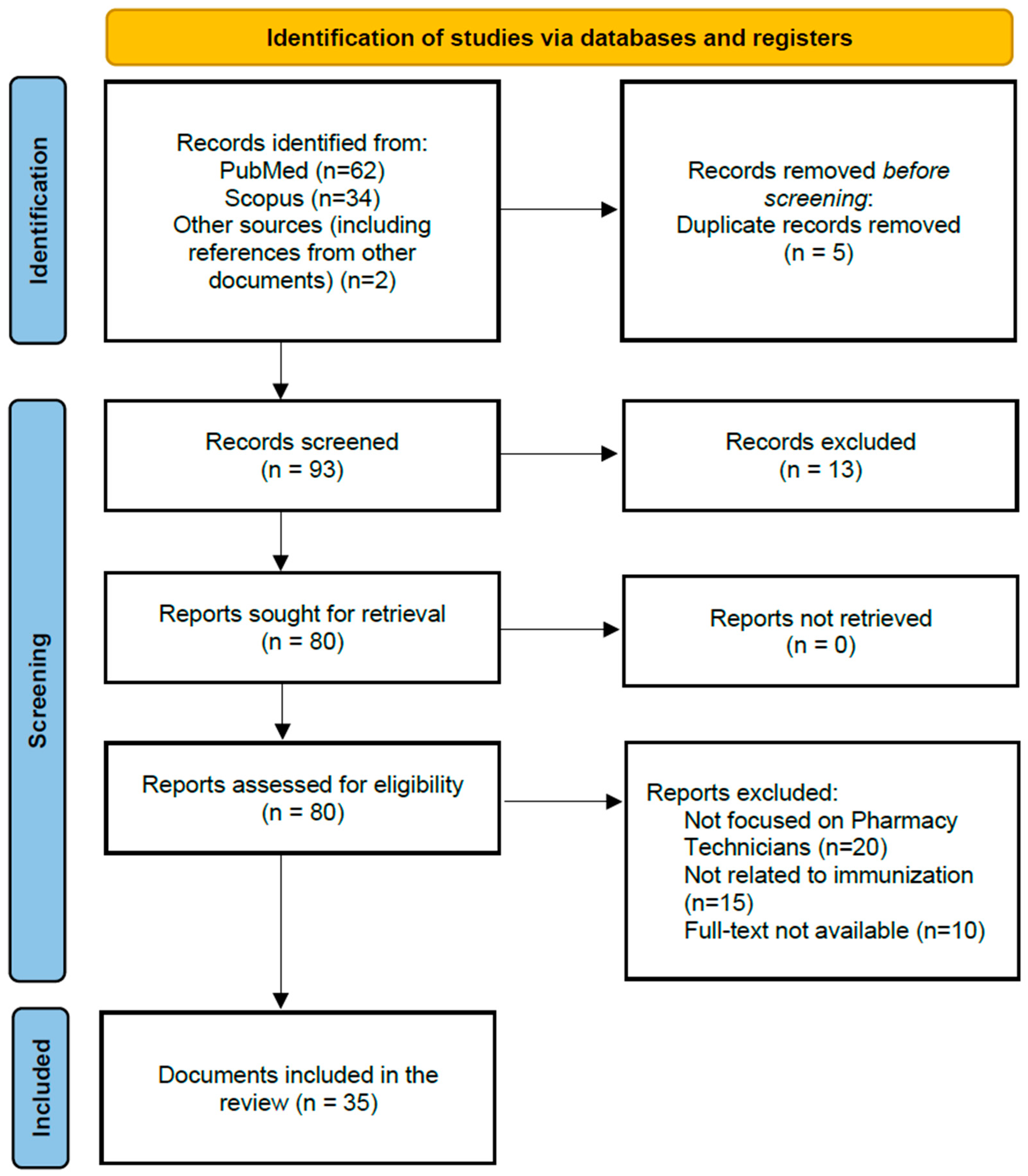

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Charting and Extraction

2.5. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Role of Pharmacy Technicians as Immunizers

3.3. Impact on Public Health

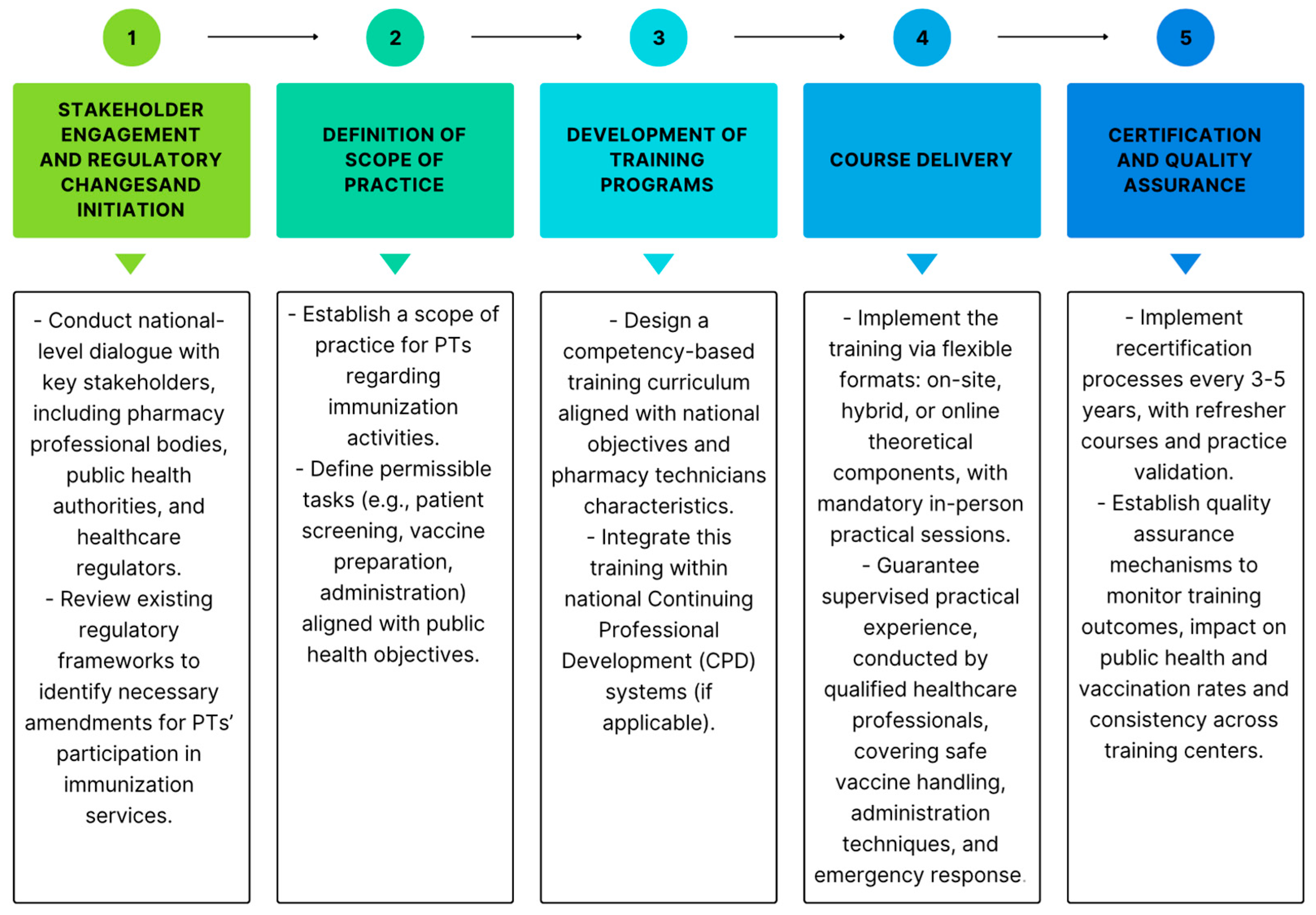

3.4. Immunization Training Programs

- Foundational knowledge modules: covering the basic concepts of immunology, anatomy, physiology, public health, and pharmacovigilance.

- Vaccine-specific modules: routes of administration, commonly used vaccines, vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine schedules, vaccine storage, handling, and disposal.

- Clinical safety: contraindications, management of adverse reactions and emergency response concepts.

- Professional role development: role of PT in immunization.

- Communication skills, particularly for patient interaction, consent procedures, and managing vaccine hesitancy.

- Practical experience, including hands-on injection practice (supervised).

- Personal safety and protection: instruction on the correct use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

- Life-saving response skills such as Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and emergency response training.

3.5. Facilitators and Opportunities

3.6. Barriers and Challenges

3.7. Implementation Guidelines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACIP | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices |

| ACPE | Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education |

| APTUK | Association of Pharmacy Technicians UK |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

| DTP | Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HepA | Hepatitis A |

| HepB | Hepatitis B |

| Hib | Haemophilus influenzae Type b |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Heading |

| MenACWY | Meningococcal Conjugate Vaccine (serogroups A, C, W, Y) |

| MMR | Measles, Mumps, Rubella |

| NS | Not Specified |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| PBI | Pharmacy-based Immunization |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| PREP Act | Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act |

| PT | Pharmacy Technician |

| Tdap | Tetanus, Diphtheria, Pertussis (adult booster) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Le, L.M.; Veettil, S.K.; Donaldson, D.; Kategeaw, W.; Hutubessy, R.; Lambach, P.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. The impact of pharmacist involvement on immunization uptake and other outcomes: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 1499–1513.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ten Health Issues WHO Will Tackle This Year. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Anderson, E.L. Recommended solutions to the barriers to immunization in children and adults. Mo. Med. 2014, 111, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goad, J.A.; Taitel, M.S.; Fensterheim, L.E.; Cannon, A.E. Vaccinations Administered During Off-Clinic Hours at a National Community Pharmacy: Implications for Increasing Patient Access and Convenience. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Immunization Efforts Have Saved at Least 154 Million Lives over the Past 50 Years. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/24-04-2024-global-immunization-efforts-have-saved-at-least-154-million-lives-over-the-past-50-years (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Shattock, A.J.; Johnson, H.C.; Sim, S.Y.; Carter, A.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.C.; Thompson, K.M.; Badizadegan, K.; Lambert, B.; Ferrari, M.J.; et al. Contribution of vaccination to improved survival and health: Modelling 50 years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet 2024, 403, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD/European Commission. Health at a Glance: Europe 2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kau, L.; Sadowski, C.A.; Hughes, C. Vaccinations in Older Adults: Focus on Pneumococcal, Influenza and Herpes zoster infections. Can. Pharm. J. 2011, 144, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, T.G.; McKeirnan, K.C.; Frazier, K.; VanVoorhis, L.; Shin, S.; Le, K. Supervising pharmacists’ opinions about pharmacy technicians as immunizers. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2019, 59, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Mancilla, M.S.; Mora-Vargas, J.; Ruiz, A. Pharmacy-based immunization: A systematic review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1152556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haems, M.; Lanzilotto, M.; Mandelli, A.; Mota-Filipe, H.; Paulino, E.; Plewka, B.; Rozaire, O.; Zeiger, J. European community pharmacists practice in tackling influenza. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2024, 14, 100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmeier, K.C.; McDonough, S.L.K.; Rein, L.J.; Brookhart, A.L.; Gibson, M.L.; Powers, M.F. Exploring the expanded role of the pharmacy technician in medication therapy management service implementation in the community pharmacy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2019, 59, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desselle, S.P.; Hoh, R.; Holmes, E.R.; Gill, A.; Zamora, L. Pharmacy technician self-efficacies: Insight to aid future education, staff development, and workforce planning. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2018, 14, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association of Pharmacy Tehcnicians. Education and Training Programmes of Pharmacy Technicians-European Survey. 2017. Available online: https://www.eapt.info/resources/PDF-Downloads/EAPT-European-Survey-(2017)-Education-and-Training_Final.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Sakr, F.; Dabbous, M.; Rahal, M.; Salameh, P.; Akel, M. Challenges and opportunities to provide immunization services: Analysis of data from a cross-sectional study on a sample of pharmacists in a developing country. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenor, J.E.; Kervin, M.S.; Halperin, D.M.; Langley, J.; Bettinger, J.A.; Top, K.A.; Lalji, F.; Slayter, K.; Kaczorowski, J.; Bowles, S.K.; et al. Pharmacists as immunizers to Improve coverage and provider/recipient satisfaction: A prospective, Controlled Community Embedded Study with vaccineS with low coverage rates (the Improve ACCESS Study): Study summary and anticipated significance. Can. Pharm. J. 2020, 153, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU). The Role of Community Pharmacists in Vaccination; PGEU: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco, M.; Carter, C.; Houle, S.K.D.; Waite, N.M. The role of pharmacy technicians in vaccination services: A scoping review. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 15–26.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.J.; Bright, D.; Adams, J. Pharmacy technician-administered immunizations: A five-year review. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, M.F.; Hohmeier, K.C. Pharmacy technicians and immunizations. J. Pharm. Technol. 2011, 27, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Pharmaceutical Federation. Policy Progress, Stakeholder Engagement and Challenges in Pharmacist-Led Vaccination. 2025. Available online: https://www.fip.org/file/6208 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- DiMario, A.; McCall, K.L.; Couture, S.; Boynton, W. Pharmacist and Pharmacy Technician Attitudes and Experiences with Technician-Administered Immunizations. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeer, Y.A.; Mousa, A.A.B.; Hagawi, I.M.; Alkhathami, A.H.; Alshammari, M.N. Pharmacy Technicians’ Role in Managing Pharmacy Operations During COVID-19: Challenges, Adaptations, and Impact on Workflow and Patient Care. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Multidiscip. Phys. Sci. 2011, 13, 231138. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, L.A.; Branham, A.R.; Dalton, E.E.; Moose, J.S.; Marciniak, M.W. Implementation of a vaccine screening program at an independent community pharmacy. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017, 57, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattin, A.J. Disparities in the Use of Immunization Services Among Underserved Minority Patient Populations and the Role of Pharmacy Technicians: A Review. J. Pharm. Technol. 2017, 35, 171–176. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/8755122517717533 (accessed on 2 June 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.D.; Anderegg, S.V.; Couldry, R.J. Development of a Pharmacy Technician–Driven Program to Improve Vaccination Rates at an Academic Medical Center. Hosp. Pharm. 2017, 52, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, D.; Adams, A.J. Pharmacy technician-administered vaccines in Idaho. Am. J Health Syst. Pharm. 2017, 74, 2033–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, D.; Adams, A.; Bright, D. Should Pharmacy Technicians Administer Immunizations? Innov. Pharm. 2017, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeirnan, K.C.; Frazier, K.R.; Nguyen, M.; MacLean, L.G. Training pharmacy technicians to administer immunizations. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2018, 58, 174–178.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrick, S.C.; Patterson, B.J.; Kader, M.S.; Rashid, S.; Buck, P.O.; Rothholz, M.C. National survey of pharmacy-based immunization services. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5657–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeirnan, K.C.; McDonough, R.P. Transforming pharmacy practice: Advancing the role of technicians. Pharm. Today 2018, 24, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucette, W.R.; Schommer, J.C. Pharmacy Technicians’ Willingness to Perform Emerging Tasks in Community Practice. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.J.; Desselle, S.P.; McKeirnan, K.C. Pharmacy Technician-Administered Vaccines: On Perceptions and Practice Reality. Pharmacy 2018, 6, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huston, S.A.; Ha, D.R.; Hohmann, L.A.; Hastings, T.J.; Garza, K.B.; Westrick, S.C. Qualitative Investigation of Community Pharmacy Immunization Enhancement Program Implementation. J. Pharm. Technol. 2019, 35, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, D.; Osborne, J.; Borowicz, B. Moving the Needle: A 50-State and District of Columbia Landscape Review of Laws Regarding Pharmacy Technician Vaccine Administration. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavaza, P.; Hackworth, Z.; Ho, T.; Kim, H.; Lopez, Z.; Mamhit, J.; Vasquez, M.; Vo, J.; Kwahara, N.; Zough, F. California Pharmacists’ and Pharmacy Technicians’ Opinions on Administration of Immunizations in Community Pharmacies by Pharmacy Technicians. J. Contemp. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 67, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, T.G.; McKeirnan, K.C. Perceived Benefit of Immunization-Trained Technicians in the Pharmacy Workflow. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, R. Embracing the Evolution of Pharmacy Practice by Empowering Pharmacy Technicians. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.N.; Nørgaard, L.S.; Hedegaard, U.; Søndergaard, L.; Servilieri, K.; Bendixen, S.; Rossing, C. Integration of and visions for community pharmacy in primary health care in Denmark. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 19, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeirnan, K.C.; Kaur, S. Pharmacy patient perceptions of pharmacy technicians as immunizers. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkmon, W.; Barnard, M.; Rosenthal, M.; Desselle, S.; Holmes, E. Community pharmacist perceptions of increased technician responsibility. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 382–389.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmeier, K.C.; McKeirnan, K.C. Pharmacy Technicians Are Valued More than Ever: Insights into a Team-Centered Immunization Approach; Pharmacy Times: Cranbury, NJ, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/pharmacy-technicians-are-valued-more-than-ever-insights-into-a-team-centered-immunization-approach (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- McKeirnan, K.C.; Hanson, E. A qualitative evaluation of pharmacy technician opinions about administering immunizations. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2023, 10, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.J. Extending COVID-19 Pharmacy Technician Duties: Impact on Safety and Pharmacist Jobs. J. Pharm. Technol. 2023, 39, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaagd, G.; Pugh, A. Pharmacists’ Expanding Role in Immunization Practices. 2023. Available online: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/pharmacists-expanding-role-in-immunization-practices (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Fuschetto, K.S.; Amin, K.A.; Gothard, M.D.; Merico, E.M. Evaluating the Role of Pharmacy Technician-Administered Vaccines. J. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 36, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, N.; Jackson, B.N.; Durham, S.H.; Hohmann, N.S.; Westrick, S.C. Qualitative analysis of community pharmacy–based COVID-19 immunization service operations. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 1574–1582.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, K.A.; Taylor, A.D. A consensus building study to define the role of a ‘clinical’ pharmacy technician in a primary care network environment in England. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 31, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miran, N.K.; DeLor, B.; Baker, M.; Fakhouri, J.; Metz, K.; Huskey, E.; Kilgore, P.; Fava, J.P. Vaccine administration by pharmacy technicians: Impact on vaccination volume, pharmacy workflow and job satisfaction. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2024, 13, 100397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadi, A.; Thirion, D.J.G.; Waite, N.M.; David, P.-M. Key stakeholder perspectives on delivery of vaccination services in Quebec community pharmacies. Can. Pharm. J. 2024, 157, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayenew, W.; Anagaw, Y.K.; Limenh, L.W.; Simegn, W.; Bizuneh, G.K.; Bitew, T.; Minwagaw, T.; Fitigu, A.E.; Dessie, M.G.; Asmamaw, G. Readiness of and barriers for community pharmacy professionals in providing and implementing vaccination services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hursman, A.; Wanner, H.; Rubinstein, E. Empowering pharmacy technicians as vaccine champions: A pilot study in independent community pharmacies. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2025, 65, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeirnan, K.; Sarchet, G. Implementing Immunizing Pharmacy Technicians in a Federal Healthcare Facility. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Roles of Pharmacy Technicians. 2019. Available online: https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/statements/roles-of-pharmacy-technicians.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Woodford, A. 10 Essential Responsibilities of an Immunization Technician. Insight Global. 2024. Available online: https://insightglobal.com/blog/immunization-technician-responsibilities/ (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Matos, C.; Rodrigues, L.; Joaquim, J. Attitudes and opinions of Portuguese community pharmacy professionals towards patient reporting of adverse drug reactions and the pharmacovigilance system. Drugs Ther. Perspect. 2017, 33, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Sharps Disposal Containers in Health Care Facilities. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/safely-using-sharps-needles-and-syringes-home-work-and-travel/sharps-disposal-containers-health-care-facilities (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- CDC. Safe and Proper Sharps Disposal During a Mass Vaccination Campaign. In: Healthcare Workers. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/healthcare/hcp/pandemic/sharps-disposal-mass-vaccination.html (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- G/Michael Beyene, K.; Tamiru, M.T. Quality and safety requirements for pharmacy-based vaccination in resource-limited countries. Trop. Med. Health 2025, 53, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, V. Pharmacy Technicians and the COVID 19 Vaccination Programme. 2020. Available online: https://www.aptuk.org/news/pharmacy-technicians-and-the-covid-19-vaccination-programme (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Gerges, S.; Gudzak, V.; Bowles, S.; Logeman, C.; Fadaleh, S.A.; Bucci, L.M.; Taddio, A. Experiences of community pharmacists administering COVID-19 vaccinations: A qualitative study. Can. Pharm. J. 2023, 156, 7S–17S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, K.T.; Cullison, M.A. Deficiencies in Immunization Education and Training in Pharmacy Schools: A Call to Action. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009, 73, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (n.d.). PREP Act|Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act. Available online: https://aspr.hhs.gov:443/legal/PREPact/pages/default.aspx (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- American Disease Prevention Coalition. Pharmacy Technician Vaccination Authority. 2025. Available online: https://vaccinesshouldntwait.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/ADPC-Technician-Factsheet-update-2025_00.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Leslie, K.F.; Waltz, P.; DeJarnett, B.; Fuller, L.Z.; Lisenby, S.; Raake, S.E. Evaluation of technician immunization administration. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardet, J.-D.; Combe, J.; Tanty, A.; Louvier, P.; Granjon, M.; Allenet, B. Optimizing work in community pharmacy: What preferences do community pharmacists and pharmacy technicians have for a better allocation of daily activities? Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2025, 17, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EHR. Vaccination à l’officine par les Préparateurs en Pharmacie. CFA Pharmacie. 2024. Available online: https://www.cfapharmacie.com/blog/vaccination-a-lofficine/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Paitraud, D. Vaccination: Élargissement des Compétences des Préparateurs en Pharmacie et Autres Évolutions. 2024. Available online: https://www.vidal.fr/actualites/31090-vaccination-elargissement-des-competences-des-preparateurs-en-pharmacie-et-autres-evolutions.html (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Boots, U.K. Boots UK—Boots UK Report Successful Trial of Pharmacy Technicians Providing Childhood Flu Vaccinations on Isle of Wight. 2019. Available online: https://www.boots-uk.com/newsroom/features/boots-uk-report-successful-trial-of-pharmacy-technicians-providing-childhood-flu-vaccinations-on-isle-of-wight/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Burns, C. Pharmacy technicians can administer flu vaccine under national protocol for England. Pharm. J. 2021, 307, 7953. Available online: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/news/pharmacy-technicians-can-administer-flu-vaccine-under-national-protocol-for-england (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Kulczycki, A.; Grubbs, J.; Hogue, M.D.; Shewchuk, R. Community chain pharmacists’ perceptions of increased technicians’ involvement in the immunization process. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenor, J.E.; Bowles, S.K. Evidence for pharmacist vaccination. Can. Pharm. J. 2018, 151, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobell, J.T.; Moss, J.; Creelman, J.; Christensen, R.; Jensen, B.; Stewart, J.; Ameel, K.; Asfour, F. Implementation of a comprehensive pharmacy-driven immunization care process model in a pediatric cystic fibrosis clinic. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, A.N.; Mattingly, T.J. Advancing the role of the pharmacy technician: A systematic review. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2018, 58, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamboulian, D.; Soler, L.; Copertari, P.; Cordero, A.P.; Vázquez, H.; Valanzasca, P.; Monsanto, H.; Grabenstein, J.D.; Johnson, K.D. Policies and practices on pharmacy-delivered vaccination: A survey study conducted in six Latin American countries. Rev. Ofil·Ilaphar 2018, 28, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu, S. Making the Case: Pharmacy Technicians as Vaccine Providers|BC Pharmacy Association. 2025. Available online: https://www.bcpharmacy.ca/tablet/winter-25/making-case-pharmacy-technicians-vaccine-providers (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Gettman, D. The Expanding Role of Pharmacists in Immunization: A Cornerstone of Modern Pharmacy Practice. In Proceedings of the Monthly Presentations on the Most Innovative Twenty Changes in Pharmacy Practice over the Last Two Decades, Buffalo, NY, USA, April 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, D.; Abou-Abbas, L.; Farhat, S.; Hassan, H. Pharmacists as immunizers in Lebanon: A national survey of community pharmacists’ willingness and readiness to administer adult immunization. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccinations Training|PSI. Available online: https://www.psi.ie/education-and-training/vaccinations-training (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- WHO Immunization Training Materials. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/essential-programme-on-immunization/training (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- PTCB—Immunization Administration. Available online: https://www.ptcb.org (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Immunization Administration Training for Pharmacy Technicians—CEimpact. Available online: https://www.ceimpact.com/training/immunization-administration-training-for-pharmacy-technicians/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Vaccination including Basic Life Support and Anaphylaxis Training. Available online: https://cb-training.com/vaccination-training/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- PLURAL—Administração de Vacines e Injetáveis. Available online: https://www.plural.pt (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Pharmacy Technician Online Training: Immunization (2024). Available online: https://www.freece.com/courses/immunization/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Vaccinology Course—ECAVI. Available online: https://e-cavi.com/registration-open-for-10th-vaccinology-course/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- PTU Elite: Immunizations. In: TRC Healthc. Available online: https://trchealthcare.com/product/ptu-elite-immunizations/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Immunisation & Vaccination Training. In ER Train. Available online: https://www.ertraining.ie/immunisation-vaccination-training (accessed on 15 April 2025).

| Author, Year | Type of Study | Country | Objective | Pharmacy Technician Role | Vaccination Type | Requested Education/Training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powers & Hohmeier, 2011 [20] | Literature review | USA | Identify opportunities for PTs in immunization programs | Support roles such as documentation, billing, adverse event reporting | General immunizations | CPR training recommended, but no direct administration training |

| Rhodes et al., 2016 [25] | Interventional | USA (North Carolina) | Implement a vaccine screening program in an independent community pharmacy | Identified eligible patients for vaccination | Influenza, pneumococcal, Tdap, zoster | No direct immunization training; screening role only |

| Pattin, 2017 [26] | Literature review | USA | Review disparities in immunization uptake and PTs’ roles | Assisted in documentation, billing, patient education | General immunizations | No direct administration training, but involvement in vaccine workflow |

| Hill et al., 2017 [27] | Interventional (pre–post) | USA (Kansas) | Develop a PT-driven inpatient vaccination program | Identified and screened hospitalized patients for vaccination | Influenza, pneumococcal | Training on patient screening, communication, and documentation |

| Adams and Bright, 2017 [28] | Other (letter) | USA (Idaho) | Discuss PT-administered vaccines under new state law | Administered vaccines under pharmacist supervision | General immunizations | National certification, ACPE training, basic life support certification |

| Atkinson et al., 2017 [29] | Other (commentary) | USA | Discuss potential role of technicians in vaccine administration | Administered vaccines under pharmacist supervision | General immunizations | Training in administration techniques and basic life support |

| McKeirnan et al., 2018 [30] | Interventional (pre–post) | USA (Idaho) | Evaluate the effectiveness of an immunization training program for PTs | Administered vaccines after training | General immunizations | A 4 h training program (2 h home study, 2 h live training) |

| Westrick et al., 2018 [31] | Observational (cross-sectional) | USA | National survey on pharmacy-based immunization services | Technicians supported vaccine workflow but did not administer vaccines | Influenza, pneumococcal, herpes zoster, Tdap | No direct immunization training, but involved in administrative roles |

| McKeirnan et al., 2018 [32] | Literature review | USA | Describe and support the advancement of PTs roles in community pharmacy | Administered immunizations, performed final product verification and verbal communication, and managed medication synchronization | General immunization | ACPE Certificate for PTs, basic life support certification |

| Doucette & Schommer, 2018 [33] | Observational (cross-sectional) | USA | Assess PTs’ willingness to take on emerging tasks | Low willingness to administer vaccines | General immunizations | No specific training reported |

| Adams et al., 2018 [34] | Other (letter) | USA | Discuss perceptions and realities of pharmacy technician-administered vaccines | Administered vaccines under pharmacist supervision | General immunizations | State-dependent, some required formal training |

| Bertsch et al., 2019 [9] | Qualitative study | USA | Assess the perceptions of supervising pharmacists | Administering immunizations under pharmacist supervision | General immunization | ACPE-accredited immunization training and basic life support certification |

| Huston et al., 2019 [35] | Qualitative study | USA (Alabama, California) | Assess pharmacist perceptions of a community pharmacy immunization enhancement program | PTs supported workflow, identified high-risk patients | Pneumococcal, zoster | ACPE-accredited immunization training for pharmacists and PTs |

| Eid et al., 2019 [36] | Literature review (policy analysis) | USA | Review legal landscape of PT vaccine administration across all USA | Varied by state; three states (Idaho, Rhode Island, Utah) authorized administration | General immunizations | Varies by state, some requiring formal immunization training |

| Gavaza et al., 2020 [37] | Observational (cross-sectional) | USA (California) | Assess opinions of pharmacists and PTs on allowing PTs to administer immunizations | Not currently permitted; study explores support for future authorization | General immunizations | If authorized, training would be required (e.g., ACPE-accredited programs) |

| Bertsch & McKeirnan, 2020 [38] | Qualitative study | USA | Assess pharmacists’ perceptions of immunization-trained PTs | Administered vaccines, improved workflow | General immunizations | Limited training availability identified as a barrier |

| Burke, 2020 [39] | Other (opinion) | USA | Advocate for expanding PTs roles, including immunization administration | Potential future role in vaccine administration | General immunizations | Inconsistencies in training requirements noted as a barrier |

| Hansen et al., 2021 [40] | Other (commentary) | Denmark | Analyze the evolving role of Danish community pharmacies in public health following national strategies and legislative changes. | Handle vaccinations on the responsibility of a physician for a patient group, defined by law and by the physician | Travel, influenza, pneumococcal | Not provided |

| McKeirnan et al., 2021 [41] | Observational | USA | Assess patient perceptions and acceptance of PTs serving as immunizers | Administering immunizations under pharmacist supervision | General immunization | Certified pharmacy technicians with additional immunization training and basic life support certification |

| Sparkmon et al., 2021 [42] | Observational (cross-sectional) | USA | Determine predictors of pharmacists’ comfort levels with certified and trained technicians performing advanced functions. | PTs were evaluated in roles involving verbal prescription communication, nonclinical medication therapy management support, vaccine administration and prescription verification | General immunizations | Nationally certified and trained in the specific advanced task in question |

| Hohmeier et al., 2021 [43] | Other (commentary) | USA | Explore team-centered approach to immunization in pharmacies | Assisted in vaccine workflow, documentation, and patient interaction | Influenza, COVID-19 | On-the-job training, some states required formal certification |

| Adams et al., 2022 [19] | Other (commentary) | USA | Review five years of PT-administered immunizations | Administered vaccines in various states | General immunizations | Multiple training programs available, including ACPE-approved courses |

| DiMario et al., 2022 [22] | Observational (cross-sectional) | USA | Compare pharmacists’ and PTs’ attitudes on technician-administered vaccines | Administered vaccines, handled billing and workflow | ACIP-recommended immunizations, COVID-19 | PREP Act-authorized training and state regulations |

| DeMarco et al., 2022 [18] | Literature review | Canada | Review the role of PTs in vaccination services | Screening patients, administering vaccines | General immunizations | Advocacy for accredited vaccine administration training |

| McKeirnan & Hanson, 2023 [44] | Qualitative study | USA (Idaho) | Evaluate PTs’ opinions about administering immunizations | Administered vaccines | General immunizations | State-approved immunization training |

| Adams, 2023 [45] | Interventional (experimental) | USA (Idaho) | Examine impact of expanded PTs duties during COVID-19 | Administered vaccines, conducted health testing | General immunizations | PREP Act training, state-specific regulations |

| DeMaagd & Pugh, 2023 [46] | Other (commentary) | USA | Explore the expanded role of pharmacy personnel in immunization practices | Some states allow PTs to administer vaccines under supervision | General immunizations | 11+ training programs available for PTs vaccine administration |

| Fuschetto et al., 2023 [47] | Observational (cross-sectional) | USA (Ohio) | Evaluate perceptions of pharmacy technician-administered vaccines post-COVID-19 | PTs administered vaccines under PREP Act | COVID-19, childhood vaccines | Federal PREP Act requirements: state licensure or national certification, ACPE training, CPR certification |

| McCormick et al., 2023 [48] | Qualitative study | USA | Analyze COVID-19 PBI service operations | Administered vaccines, assisted in workflow | COVID-19, routine vaccines | PREP Act training, state-specific requirements |

| Street & Taylor, 2023 [49] | Qualitative study | UK (England) | Define the role criteria for a ‘clinical’ pharmacy technician (CPT) in a Primary Care Network (PCN) setting | Future tasks: Administration of flu, COVID and Travel vaccination under a Patient Group Direction (PGD) | Flu and COVID-19 and travel (referenced under PGD) | Portfolio of competence; national frameworks; Level 5+ qualification; accredited training (e.g., CPPE pathways) |

| Miran et al., 2024 [50] | Observational (cohort) | USA | Evaluate impact of immunizing PTs on vaccination volume, workflow, and job satisfaction | Administered vaccines in community pharmacy chain | General immunizations | ACPE-approved training, CPR certification, state licensure/registration |

| Chadi et al., 2024 [51] | Qualitative study | Canada (Quebec) | Assess stakeholder perspectives on pharmacy vaccination | Assisted pharmacists in vaccine administration | General immunizations | Training and role delegation varied by pharmacy setting |

| Ayenew et al., 2024 [52] | Observational (cross-sectional) | Ethiopia | Assess readiness and barriers for pharmacy-led vaccination services | Expressed readiness, but faced regulatory and infrastructure challenges | General immunizations | Identified need for enhanced education and policy reform |

| Hursman et al., 2025 [53] | Interventional (pilot study) | USA (North Dakota) | Implement “VaxChamp” program for PTs vaccine advocacy | Advocated for vaccination, administered vaccines in some pharmacies | Pneumococcal, hepatitis B, shingles | Specialized training for advocacy, varied administration training |

| McKeirnan & Sarchet, 2025 [54] | Interventional | USA (Arizona) | Implement immunizing PTs in a federal healthcare facility | Administered vaccinations in a federal health system (Whiteriver Service Unit) | Various vaccines | Accredited immunization training from Washington State University |

| Intervention on Immunization Process Phase | Competency/Role | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Before | Inventory management | Manage vaccine storage, stock rotation and ordering [20,55]. |

| Before | Patient screening support | Distribute and help with form filling, collecting patient information and identifying potential issues [18,20]. |

| All phases (Before, During, After) | Work with other healthcare professionals | Work with local prescribers and healthcare departments to increase the size of vaccinated population and decrease the size of the public pool in which disease may reside [55]. |

| All phases (Before, During, After) | Educate and communicate with the general public | Advocate for the appropriate use of vaccinations among the public [18]. |

| During | Vaccine administration (in different countries/areas jurisdictions) | Administer vaccines (where legally allowed and with proper training) [18,20,22,29,36,44,54,55]. |

| During, After | Monitor and report adverse reactions to vaccines | Know how to report any vaccine side effects to the responsible authority [56,57]. |

| During, After | Sharp material handling and disposal | Safe preparation and disposal of sharp material, following accepted protocols (CDC’s Safe Injection Practices and FDA guidelines) and OSHA [18,55,58,59]. |

| During, After | Keep immunization records | Accurately documenting immunization registries [55]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valeiro, C.; Silva, V.; Balteiro, J.; Patterson, D.; Bezerra, G.; Mealiff, K.; Matos, C.; Jesus, Â.; Joaquim, J. Pharmacy Technicians in Immunization Services: Mapping Roles and Responsibilities Through a Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151862

Valeiro C, Silva V, Balteiro J, Patterson D, Bezerra G, Mealiff K, Matos C, Jesus Â, Joaquim J. Pharmacy Technicians in Immunization Services: Mapping Roles and Responsibilities Through a Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151862

Chicago/Turabian StyleValeiro, Carolina, Vítor Silva, Jorge Balteiro, Diane Patterson, Gilberto Bezerra, Karen Mealiff, Cristiano Matos, Ângelo Jesus, and João Joaquim. 2025. "Pharmacy Technicians in Immunization Services: Mapping Roles and Responsibilities Through a Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151862

APA StyleValeiro, C., Silva, V., Balteiro, J., Patterson, D., Bezerra, G., Mealiff, K., Matos, C., Jesus, Â., & Joaquim, J. (2025). Pharmacy Technicians in Immunization Services: Mapping Roles and Responsibilities Through a Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(15), 1862. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151862