Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Healthcare Professionals: A Hospital-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Basic and Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

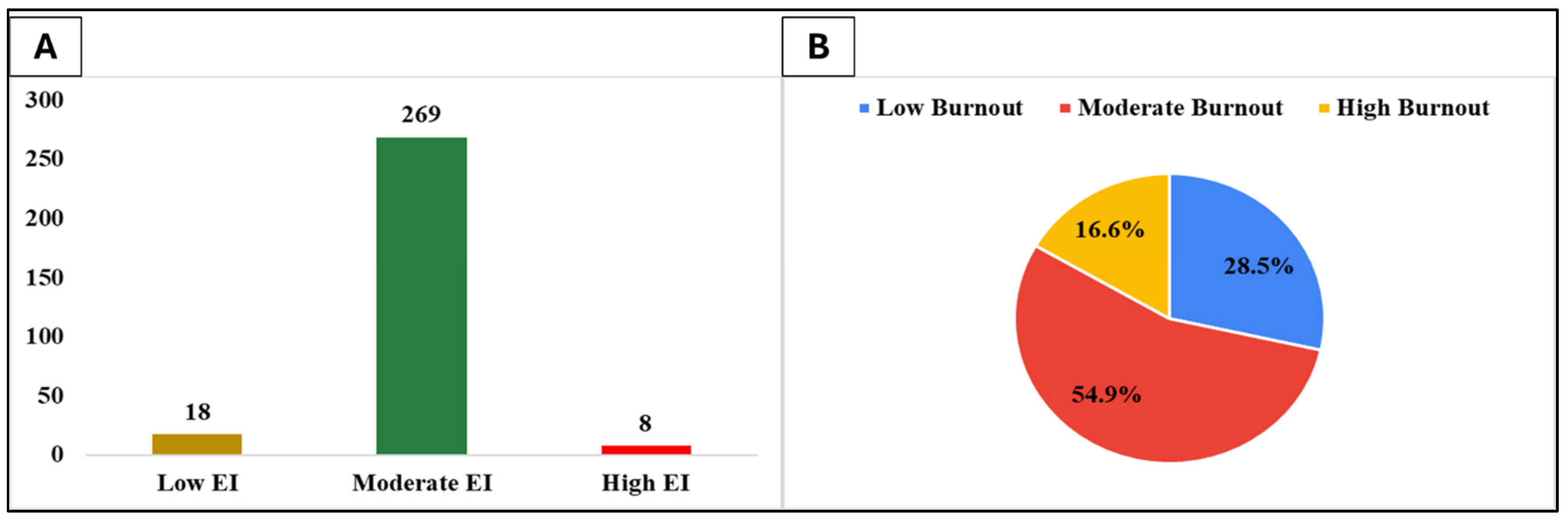

3.2. Emotional Intelligence and Burnout Levels of Healthcare Professionals

3.3. Comparison of EI and Burnout Scores

3.4. Relation Between Emotional Intelligence and Burnout

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings, and implications. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M.; Thorsteinsson, E.B. A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V.; Furnham, A. Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. Eur. J. Pers. 2001, 15, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J. Pers. 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.L.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T.P. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure, and Health; Pennebaker, J.W., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Working with Emotional Intelligence; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H.C.; Hung, C.M.; Liu, Y.T.; Cheng, Y.J.; Yen, C.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Huang, C.K. Associations between emotional intelligence and doctor burnout, job satisfaction, and patient satisfaction. Med. Educ. 2011, 45, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerjordet, K.; Severinsson, E. Emotional intelligence in mental health nurses talking about practice. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2004, 13, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.; Williams, B.; McKenna, L. Emotional intelligence training to reduce burnout in emergency physicians: A randomized controlled trial. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2023, 28, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J. Emotional intelligence and burnout in emergency medical staff: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, J.; Alshehry, A.; Alsuhaibani, R. Burnout among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Majmaah Health Directorate. Annual Health Report 2023; Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023.

- De Beer, L.T.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Investigating the validity of the short form Burnout Assessment Tool: A job demands-resources approach. Afr. J. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 4, a95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K.V. Psychometric properties of the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TEIQue). In Assessing Emotional Intelligence: Theory, Research, and Applications; Stough, C., Saklofske, D.H., Parker, J.D.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, K.M.; Dean, A.; Soe, M.M. On academics: OpenEpi: A web-based epidemiologic and statistical calculator for public health. Public Health Rep. 2009, 124, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenezi, N.K.; Alyami, A.H.; Alrehaili, B.O.; Arruhaily, A.A.; Alenazi, N.K.; Al-Dubai, S.A. Prevalence and associated factors of burnout among saudi resident doctors: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Alpha Psychiatry 2022, 23, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Urquiza, J.L.; Monsalve-Reyes, C.S.; San Luis-Costas, C.; Fernández-Castillo, R.; Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Cañadas-De la Fuente, G.A. Factores asociados al desarrollo de burnout en enfermería: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2017, 91, e1–e15. [Google Scholar]

- AlSuliman, M.A.; AlOtaibi, S.M.; AlHarbi, T.S. Emotional intelligence and resilience among healthcare workers in Riyadh: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Med. J. 2023, 44, 502–510. [Google Scholar]

- AlHadi, A.N.; AlAteeq, D.A.; AlShahrani, S.M.; AlSudairy, N.A. The role of emotional intelligence in mitigating burnout among Saudi nurses. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 16, 321–328. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.; Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Carlasare, L.E.; Sinsky, C. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 2243–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Alrawashdeh, H.M.; Alzawahreh, M.K.; Al-Tamimi, A.; Elkholy, M.; Al Sarireh, F.; Alhaj-Mikati, D.; Al-Fraihat, D.; Bani-Issa, A.; Alkhawaldeh, A.; et al. The battle against COVID-19 in Jordan: An overview of the psychosocial challenges among healthcare workers. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1158847. [Google Scholar]

- AlBlooshi, A.; Al-Mahrezi, A.; Al-Zakwani, I.; Al-Adawi, S. Burnout and its correlates among healthcare professionals in the United Arab Emirates. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2024, 24, e45–e52. [Google Scholar]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Erwin, P.J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2018, 392, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, A.K.; Amrutha, V.N.; Bhardwaj, P. Burnout among healthcare workers in India: A post-pandemic analysis. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 27, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- AlJohani, K.A.; AlGhamdi, F.S.; Alzahrani, R.A. Patient load and burnout: A survey of emergency department physicians in Jeddah. J. Emerg. Med. Trauma. Acute Care 2023, 2023, 3. [Google Scholar]

- AlRasheed, R.; AlHarbi, A.M.; AlMutairi, A.; Alqahtani, A. Post-pandemic burnout among nurses in Riyadh: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e2098. [Google Scholar]

- AlQahtani, S.M.; AlAteeq, M.A.; AlHadi, A.N. Emotional intelligence training for healthcare professionals: A pre-post intervention study in Riyadh. J. Health Spec. 2023, 11, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Al Kuwaiti, A.; Al Shehri, A.; Subbarayalu, A.V. Emotional intelligence and job satisfaction among healthcare workers in Abu Dhabi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Alvi, T.; Nadakuditi, R.L.; Alotaibi, T.H.; Aisha, A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Ahmad, S. Emotional intelligence and academic performance among medical students-a correlational study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altwijri, S.; Alotaibi, A.; Alsaeed, M.; Alsalim, A.; Alatiq, A.; Al-Sarheed, S.; Agha, S.; Omair, A. Emotional intelligence and its association with academic success and performance in medical students. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almansour, A.M. The level of emotional intelligence among Saudi nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Belitung Nurs. J. 2023, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, K.; Joshi, S.; Raichaudhuri, A.; Ryali, V.S.; Bhat, P.S.; Shashikumar, R.; Prakash, J.; Basannar, D. Emotional intelligence scale for medical students. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2011, 20, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararajan, S.; Gopichandran, V. Emotional intelligence among medical students: A mixed methods study from Chennai, India. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, E.M.; Cronin, P.A.; Offiah, G. Emotional intelligence assessment in a graduate entry medical school curriculum. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, C.G.; Eldin, K.W.; Padmanabhan, V.; Friedman, E.M. Twelve tips for the introduction of emotional intelligence in medical education. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.R. Emotional intelligence as a crucial component to medical education. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2015, 6, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omid, A.; Haghani, F.; Adibi, P. Clinical teaching with emotional intelligence: A teaching toolbox. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2016, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, B.H.; Zain, A.M.; Hassan, F. Emotional intelligence and academic performance in first and final year medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.J.; Cook, C.E.; Hilton, T.N. Does emotional intelligence influence success during medical school admissions and program matriculation?: A systematic review. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2016, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewsnap, M.A.; Arroliga, A.C.; Adair-White, B.A. The lived experience of medical training and emotional intelligence. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2021, 34, 744–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, M.; Visentin, D.; West, S.; Lopez, V.; Kornhaber, R. Promoting emotional intelligence and resilience in undergraduate nursing students: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghahramani, S.; Jahromi, A.T.; Khoshsoroor, D.; Seifooripour, R.; Sepehrpoor, M. The relationship between emotional intelligence and happiness in medical students. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2019, 31, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsufyani, A.M.; Aboshaiqah, A.E.; Alshehri, F.A.; Alsufyani, Y.M. Impact of emotional intelligence on work performance: The mediating role of occupational stress among nurses. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2022, 54, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeneessier, A.S.; Azer, S.A. Exploring the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among academics and clinicians at King Saud University. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammari, F.; Pasay-An, E.; Gonzales, F.; Torres, S. Emotional intelligence and authentic leadership among Saudi nursing leaders in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Prof. Nurs. 2020, 36, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczygiel, D.D.; Mikolajczak, M. Emotional intelligence buffers the effects of negative emotions on job burnout in nursing. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.; Molero Jurado, M.D.; Martos Martínez, Á.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Burnout and engagement: Personality profiles in nursing professionals. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasiah, R.; Turner, J.J.; Ho, Y.F. The impact of emotional intelligence on work performance: Perceptions and reflections from academics in malaysian higher educationobitat endiaest que. Contemp. Econ. 2019, 13, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, N. Emotional intelligence and stress in medical students performing surgical tasks. Indian J. Public Health 2016, 60, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kun, B.; Demetrovics, Z. Emotional intelligence and addictions: A systematic review. Subst. Use Misuse 2010, 45, 1131–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrubaiee, L.; Alkaa’ida, F. The mediating effect of patient satisfaction in the patients’ perceptions of healthcare quality-patient trust relationship. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2011, 3, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizkhani, R.; Maghami-Mehr, A.; Isfahani, M.N. The effect of training on the promotion of emotional intelligence and its indirect role in reducing job stress in the emergency department. Front. Emerg. Med. 2021, 6, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rodríguez, D.; Molero Jurado, M.D.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.; Arrogante, O.; Oropesa-Ruiz, N.F.; Gázquez-Linares, J.J. The effects of a non-technical skills training program on emotional intelligence and resilience in undergraduate nursing students. Healthcare 2022, 10, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Gao, L.; Fan, L.; Jiao, M.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y. The influence of emotional intelligence on job burnout of healthcare workers and mediating role of workplace violence: A cross sectional study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 892421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louwen, C.; Reidlinger, D.; Milne, N. Profiling health professionals’ personality traits, behaviour styles and emotional intelligence: A systematic review. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.; Kim, J.; Park, J.; Lee, M. Influential effects of emotional intelligence on the relationship between job stress and burnout among general hospital administrative staff. Healthcare 2022, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetbuje, B.G.; Olaleye, B.R. Relationship between emotional intelligence, emotional labour, job stress and burnout: Does coping strategy work? J. Intell. Stud. Business 2022, 12, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanio, M.S.; La Grutta, S.; Piombo, M.A.; Riolo, M.; Spicuzza, V.; Franco, M.; Mancini, G.; De Pascalis, L.; Trombini, E.; Andrei, F. Hopelessness and burnout in Italian healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of trait emotional intelligence. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1146408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariatpanahi, G.; Asadabadi, M.; Rahmani, A.; Effatpanah, M.; Ghazizadeh Esslami, G. The impact of emotional intelligence on burnout aspects in medical students: Iranian research. Educ. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5745124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khesroh, E.; Butt, M.; Kalantari, A.; Leslie, D.L.; Bronson, S.; Rigby, A.; Aumiller, B. The use of emotional intelligence skills in combating burnout among residency and fellowship program directors. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.Y.; Lee, S.E.; Morse, B.L. Understanding Burnout in School Nurses: The Role of Job Demands, Resources, and Positive Psychological Capital. J. Sch. Nurs. 2025, 10598405251342532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamanzadeh, A.; Eckert, M.; Corsini, N.; Adelson, P.; Sharplin, G. Mental health of Australian frontline nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a large national survey. Health Policy 2025, 151, 105214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 119 | 40.3% |

| Male | 176 | 59.7% |

| Age | ||

| 20–30 | 68 | 23.1% |

| 30–40 | 126 | 42.7% |

| 40–50 | 74 | 25.1% |

| 50–60 | 27 | 9.2% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 205 | 69.5% |

| Single | 90 | 30.5% |

| Monthly Income (SAR) | ||

| Less than 10,000 | 59 | 20.0% |

| From 10,000 to 15,000 | 129 | 43.7% |

| From 16,000 to 25,000 | 103 | 34.9% |

| More than 25,000 | 4 | 1.4% |

| Place of Residence | ||

| In Al Majmaah | 257 | 87.1% |

| Outside the Al Majmaah | 38 | 12.9% |

| Years of Experience | ||

| Less than 5 | 58 | 19.7% |

| From 5 to 10 | 118 | 40.0% |

| From 10 to 20 | 75 | 25.4% |

| More than 20 | 44 | 14.9% |

| Daily Working Hours | ||

| Less than 8 | 14 | 4.7% |

| 8 h | 218 | 73.9% |

| From 9 to 12 | 56 | 19.0% |

| More than 12 | 7 | 2.4% |

| Frequency of On-Call Duties Per Month | ||

| None | 135 | 45.8% |

| From 1–2 | 60 | 20.3% |

| From 3–4 | 61 | 20.7% |

| From 5–6 | 22 | 7.5% |

| More than 6 | 17 | 5.8% |

| Number of Clinics Attended Per Week | ||

| None | 162 | 54.9% |

| 1 | 19 | 6.4% |

| 2 | 34 | 11.5% |

| 3 | 42 | 14.2% |

| 4 | 13 | 4.4% |

| ≥5 | 25 | 8.5% |

| Number of Patients Treated Per Week | ||

| None | 68 | 23.1% |

| Less than 15 | 77 | 26.1% |

| From 16–30 | 71 | 24.1% |

| From 31–45 | 38 | 12.9% |

| From 46–60 | 16 | 5.4% |

| More than 60 | 25 | 8.5% |

| Aspects | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.54 | 0.788 |

| Self-control | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.23 | 0.837 |

| Emotionality | 1.00 | 7.00 | 3.88 | 0.867 |

| Sociability | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.24 | 0.838 |

| Overall EI score | 1.20 | 6.87 | 4.20 | 0.601 |

| Total Burnout score | 14.0 | 70.0 | 39.36 | 11.13 |

| Variables | EI | p-Value 1 | Burnout | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Gender a | Female | 4.23 ± 0.610 | 0.485 | 39.86 ± 11.09 | 0.628 |

| Male | 4.18 ± 0.596 | 39.03 ± 11.17 | |||

| Age b | 20–30 | 4.29 ± 0.678 | 0.203 | 38.57 ± 10.78 | <0.001 ** |

| 30–40 | 4.24 ± 0.577 | 36.54 ± 11.86 | |||

| 40–50 | 4.09 ± 0.506 | 43.03 ± 9.27 | |||

| 50–60 | 4.17 ± 0.720 | 44.48 ± 8.84 | |||

| Marital status a | Married | 4.22 ± 0.606 | 0.519 | 38.20 ± 11.59 | 0.004 ** |

| Single | 4.17 ± 0.593 | 42.00 ± 9.55 | |||

| Monthly Income (SAR) b | Less than 10,000 | 4.46 ± 0.657 | 0.004 ** | 34.00 ± 11.47 | <0.001 ** |

| From 10,000 to 15,000 | 4.16 ± 0.549 | 38.81 ± 11.38 | |||

| From 16,000 to 25,000 | 4.13 ± 0.608 | 43.12 ± 9.18 | |||

| More than 25,000 | 4.03 ± 0.242 | 39.75 ± 11.84 | |||

| Years of Experience b | Less than 5 | 4.30 ± 0.594 | 0.557 | 39.67 ± 11.05 | 0.376 |

| From 5 to 10 | 4.16 ± 0.607 | 38.02 ± 11.11 | |||

| From 10 to 20 | 4.21 ± 0.570 | 40.53 ± 11.44 | |||

| More than 20 | 4.20 ± 0.652 | 40.57 ± 10.72 | |||

| Variables | EI | p-Value 1 | Burnout | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Daily Working Hours | Less than 8 | 4.37 ± 0.860 | 0.713 | 32.93 ± 13.86 | 0.107 |

| 8 h | 4.20 ± 0.599 | 39.61 ± 10.66 | |||

| From 9 to 12 | 4.17 ± 0.554 | 39.43 ± 11.30 | |||

| More than 12 | 4.30 ± 0.498 | 44.14 ± 15.77 | |||

| Frequency of On-Call Duties Per Month | None | 4.28 ± 0.616 | 0.020 * | 38.02 ± 11.22 | <0.001 ** |

| From 1–2 | 4.22 ± 0.580 | 34.55 ± 11.02 | |||

| From 3–4 | 4.07 ± 0.566 | 44.13 ± 9.04 | |||

| From 5–6 | 3.94 ± 0.588 | 45.77 ± 6.38 | |||

| More than 6 | 4.39 ± 0.556 | 41.59 ± 12.78 | |||

| Number of Clinics Attended Per Week | None | 4.24 ± 0.631 | 0.215 | 37.07 ± 11.41 | <0.001 ** |

| 1 | 4.40 ± 0.720 | 39.47 ± 13.81 | |||

| 2 | 4.07 ± 0.589 | 43.12 ± 8.54 | |||

| 3 | 4.05 ± 0.505 | 46.10 ± 6.23 | |||

| 4 | 4.22 ± 0.244 | 42.31 ± 10.31 | |||

| ≥5 | 4.26 ± 0.565 | 36.20 ± 11.44 | |||

| Number of Patients Treated Per Week | None | 4.26 ± 0.519 | 0.411 | 36.43 ± 11.69 | 0.036 * |

| Less than 15 | 4.11 ± 0.610 | 40.90 ± 10.02 | |||

| From 16–30 | 4.19 ± 0.680 | 40.85 ± 10.47 | |||

| From 31–45 | 4.22 ± 0.549 | 41.55 ± 10.36 | |||

| From 46–60 | 4.15 ± 0.461 | 38.50 ± 16.02 | |||

| More than 60 | 4.39 ± 0.688 | 35.64 ± 10.55 | |||

| Emotional Intelligence Aspects | B | Std. Error | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | −2.526 | 0.812 | −3.112 | 0.002 ** |

| Self-control | −1.179 | 0.774 | −1.524 | 0.129 |

| Emotionality | 2.208 | 0.739 | 2.990 | 0.003 ** |

| Sociability | −1.289 | 0.772 | −1.670 | 0.096 |

| Overall EI score | −0.096 | 1.082 | −0.089 | 0.929 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naggar, M.A.E.; AL-Mutairi, S.M.; Al Saidan, A.A.; Al-Rashedi, O.S.; AL-Mutairi, T.A.; Al-Ruwaili, O.S.; AL-Mutairi, B.Z.; AL-Mutairi, N.M.; AL-Mutairi, F.S.; Alrashedi, A.S. Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Healthcare Professionals: A Hospital-Based Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151840

Naggar MAE, AL-Mutairi SM, Al Saidan AA, Al-Rashedi OS, AL-Mutairi TA, Al-Ruwaili OS, AL-Mutairi BZ, AL-Mutairi NM, AL-Mutairi FS, Alrashedi AS. Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Healthcare Professionals: A Hospital-Based Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151840

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaggar, Marwa Ahmed El, Sultan Mohammad AL-Mutairi, Aseel Awad Al Saidan, Olayan Shaqer Al-Rashedi, Turki Ali AL-Mutairi, Ohoud Saud Al-Ruwaili, Badr Zeyad AL-Mutairi, Nawaf Mania AL-Mutairi, Fahad Sultan AL-Mutairi, and Afrah Saleh Alrashedi. 2025. "Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Healthcare Professionals: A Hospital-Based Study" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151840

APA StyleNaggar, M. A. E., AL-Mutairi, S. M., Al Saidan, A. A., Al-Rashedi, O. S., AL-Mutairi, T. A., Al-Ruwaili, O. S., AL-Mutairi, B. Z., AL-Mutairi, N. M., AL-Mutairi, F. S., & Alrashedi, A. S. (2025). Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in Healthcare Professionals: A Hospital-Based Study. Healthcare, 13(15), 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151840