A Smartphone Application Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills for Binge Eating Episodes: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objectives and Hypotheses

- At the end of the intervention (T1), the IG will show improvements in the primary outcomes: objective and subjective binge eating frequency and binge eating symptomatology, compared to the DWL;

- At the end of the intervention (T1), the IG will show improvements in the secondary outcomes, including global levels of ED psychopathology, shape concern, weight concern, eating concern, dietary restraint, compensatory behaviors, mindfulness, emotion regulation difficulties, intuitive eating, and psychological distress, compared to the DWL. No significant differences in body mass index (BMI) are expected between groups;

- Improvements observed in the IG at T1 will be maintained at follow-up (T2);

- The DWL group will also show improvements in primary and secondary outcomes after having access to the 8-week intervention (T2);

- Users will rate the app as acceptable.

2. Materials and Methods

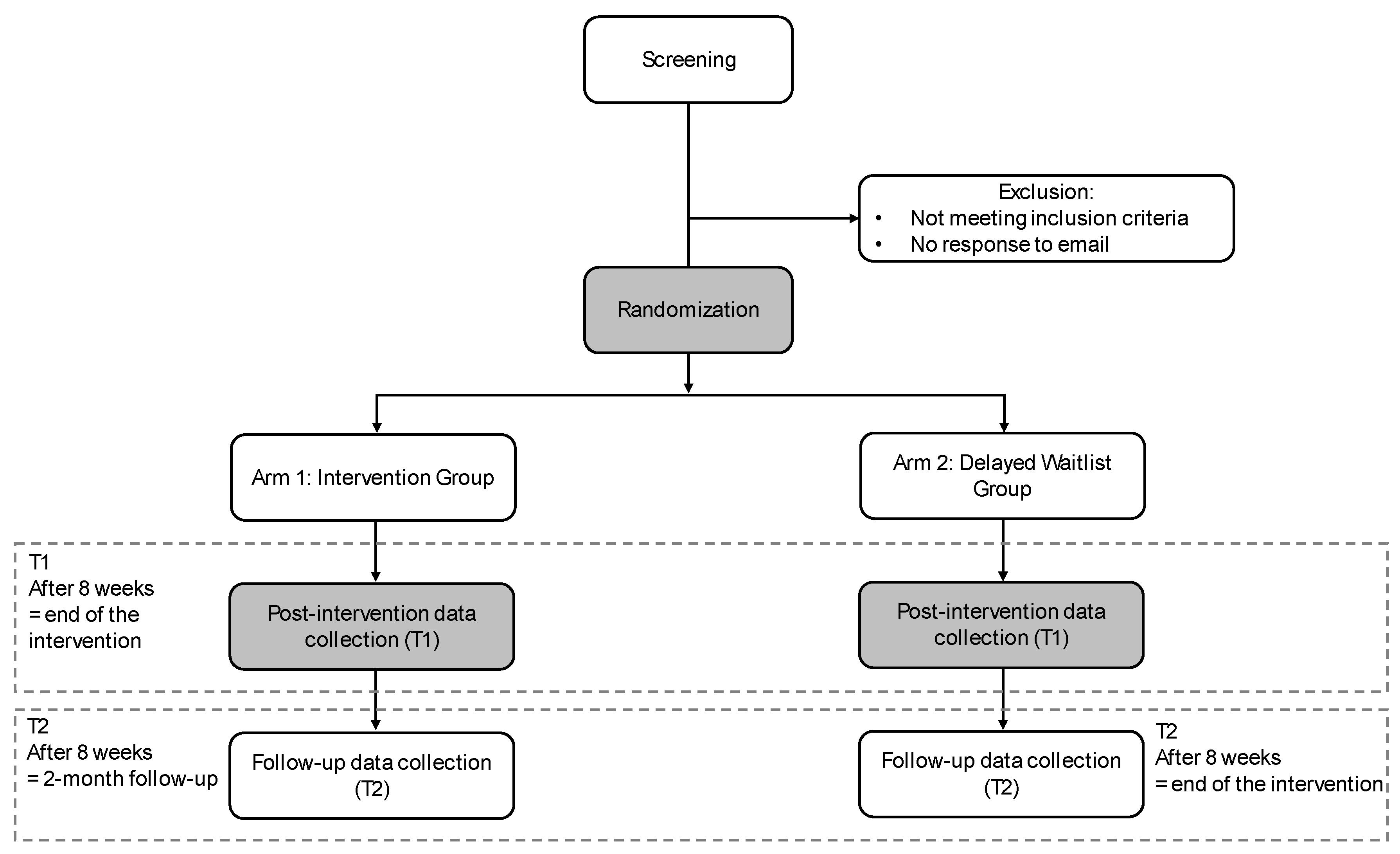

2.1. Trial Design

2.2. Participant Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Randomization Procedure

2.5. Study Conditions

2.6. eMOTE Intervention

2.7. Development and Adaptation of the Intervention

2.8. Measures

2.8.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

2.8.2. Primary Outcomes

2.8.3. Secondary Outcomes

2.8.4. Acceptability

2.8.5. Adherence

2.8.6. User Feedback

2.9. Sample Size Calculation

2.10. Statistical Analysis Plan

2.11. Data Management

2.12. Ethics and Dissemination

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C.G. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.A.; Chiu, W.T.; Deitz, A.C.; Hudson, J.I.; Shahly, V.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Benjet, C.; et al. The Prevalence and Correlates of Binge Eating Disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5–Defined Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C.N.; Rohde, P. Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2013, 122, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, S.J.; Stewart Agras, W.; Halmi, K.; Mitchell, J.E.; Kraemer, H.C. Full syndromal versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder: A multicenter study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002, 32, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withnell, S.J.; Kinnear, A.; Masson, P.; Bodell, L.P. How Different Are Threshold and Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorders? Comparing Severity and Treatment Outcome. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 784512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agras, W.S.; Bohon, C. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for the Eating Disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwood, M.E.; Friedman, A. A systematic review of enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteside, U.; Chen, E.; Neighbors, C.; Hunter, D.; Lo, T.; Larimer, M. Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eat. Behav. 2007, 8, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingemans, A.; Danner, U.; Parks, M. Emotion Regulation in Binge Eating Disorder: A Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, S.E.; Horvath, S.A. Emotion dysregulation and eating disorders. In The Oxford Handbook of Emotion Dysregulation; Beauchaine, T.P., Crowell, S.E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 327–343. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Safer, D.L.; Telch, C.F.; Chen, E.Y. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Binge Eating and Bulimia; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Safer, D.L.; Telch, C.F.; Agras, W.S. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for bulimia: A case report. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2001, 30, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telch, C.F.; Agras, W.S.; Linehan, M.M. Group dialectical behavior therapy for binge-eating disorder: A preliminary, uncontrolled trial. Behav. Ther. 2000, 31, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Porath, D.; Duthu, F.; Luo, T.; Gonidakis, F.; Compte, E.J.; Wisniewski, L. Dialectical behavioral therapy: An update and review of the existing treatment models adapted for adults with eating disorders. Eat. Disord. 2020, 28, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safer, D.L.; Robinson, A.H.; Jo, B. Outcome from a randomized controlled trial of group therapy for binge eating disorder: Comparing dialectical behavior therapy adapted for binge eating to an active comparison group therapy. Behav. Ther. 2010, 41, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, P.C.; von Ranson, K.M.; Wallace, L.M.; Safer, D.L. A randomized wait-list controlled pilot study of dialectical behaviour therapy guided self-help for binge eating disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.C.; Kenny, T.E.; Singleton, C.; Van Wijk, M.; Heath, O. Dialectical behavior therapy self-help for binge-eating disorder: A randomized controlled study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribole, E.; Resch, E. Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Anti-Diet Approach, 4th ed.; St. Martin’s Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen, E.; Tolvanen, A.; Karhunen, L.; Kolehmainen, M.; Järvelä, E.; Rantala, S.; Peuhkuri, K.; Korpela, R.; Lappalainen, R. Psychological Flexibility and Mindfulness Explain Intuitive Eating in Overweight Adults. Behav. Modif. 2015, 39, 557–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoph, M.; Järvelä-Reijonen, E.; Hooper, L.; Larson, N.; Mason, S.M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Longitudinal associations between intuitive eating and weight-related behaviors in a population-based sample of young adults. Appetite 2021, 160, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazzard, V.M.; Telke, S.E.; Simone, M.; Anderson, L.M.; Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Intuitive eating longitudinally predicts better psychological health and lower use of disordered eating behaviors: Findings from EAT 2010–2018. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, K.; Radunz, M.; McLean, S.A.; O’Shea, A.; Mavrangelos, T.; Fassnacht, D.B.; Hart, L. The Unmet Treatment Need for Eating Disorders: What Has Changed in More Than 10 Years? An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 58, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, T.; Duarte, C.; Ferreira, T.B.; Santos, C.; Martins, M.V. Smartphone Applications for Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt, T.; Michaeledes, A.; Mayhew, M.; Greif, R.; Sysko, R.; Toro-Ramos, T.; DeBar, L. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Health Coach-Delivered Smartphone-Guided Self-Help with Standard Care for Adults with Binge Eating. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; Shatte, A.; Rosato, J.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Efficacy of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral intervention for eating disorder psychopathology delivered through a smartphone app: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2020, 52, 1679–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; Anderson, C.; McClure, Z.; Liu, C.; Messer, M.; Jarman, H.K.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. A dialectical behavior therapy skills training smartphone app for recurrent binge eating: A randomized clinical trial. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 4646–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Mitchison, D.; Touyz, S.; Hay, P. Cross-sectional comparison of health-related quality of life and other features in people with and without objective and subjective binge eating using a general population sample. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownstone, L.M.; Bardone-Cone, A.M. Subjective binge eating: A marker of disordered eating and broader psychological distress. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffino, J.A.; Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Rates of Help-Seeking in US Adults with Lifetime DSM-5 Eating Disorders: Prevalence Across Diagnoses and Differences by Sex and Ethnicity/Race. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.-W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Altman, D.G.; Laupacis, A.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Krleža-Jerić, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Mann, H.; Dickersin, K.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining Standard Protocol Items for Clinical Trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, P.P.; Martins, C.; Vaz, A.R.; Conceição, E.; Bastos, A.P.; Gonçalves, S. Eating disorder examination questionnaire: Psychometric properties and norms for the Portuguese population. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2014, 22, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safer, D.L.; Adler, S.; Masson, P.C. The DBT Solution for Emotional Eating: A Proven Program to Break the Cycle of Bingeing and Out-of-Control Eating; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C.G. Overcoming Binge Eating: The Proven Program to Learn Why You Binge and How You Can Stop, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict. Behav. 1982, 7, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, C.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Ferreira, C. Expanding binge eating assessment: Validity and screening value of the Binge Eating Scale in women from the general population. Eat. Behav. 2015, 18, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregório, S.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Mindful attention and awareness: Relationships with psychopathology and emotion regulation. Span. J. Psychol. 2013, 16, E79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J.; Ribeiro, E.; Ferreirinha, R.; Dias, P. The Portuguese version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms. Rev. Psiquiatr. Clín. 2010, 37, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Mendes, A. Psychometric properties of the intuitive eating scale-2 and association with binge eating symptoms in a portuguese community sample. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2016, 16, 329–341. [Google Scholar]

- Tylka, T.L.; van Diest, A.M.K. The Intuitive Eating Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation with college women and men. J. Couns. Psychol. 2013, 60, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, S.H.; Lovibond, P.F. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd ed.; Psychology Foundation of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.; Honrado, A.; Leal, I. Contribuição para o estudo da Adaptação Portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2004, 5, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; Shatte, A.; Messer, M.; Firth, J.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. E-mental health interventions for the treatment and prevention of eating disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solaro, N.; Barbiero, A.; Manzi, G.; Ferrari, P.A. A sequential distance-based approach for imputing missing data: Forward Imputation. Adv. Data Anal. Classif. 2017, 11, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, C.E. Understanding the Intention-to-treat Principle in Randomized Controlled Trials. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 18, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, I. ggstatsplot: ‘ggplot2’ Based Plots with Statistical Details, Version 0.13.0; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kabacoff, R.I. R in Action, Data Analysis and Graphics with R, 2nd ed.; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Juarascio, A.S.; Manasse, S.M.; Goldstein, S.P.; Forman, E.M.; Butryn, M.L. Review of Smartphone Applications for the Treatment of Eating Disorders. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2015, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, K.C.; Peterson, C.B.; Frazier, P.; Crow, S.J. Convergence of scores on the interview and questionnaire versions of the Eating Disorder Examination: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Assess. 2011, 23, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celio, A.A.; Wilfley, D.E.; Crow, S.J.; Mitchell, J.; Walsh, B.T. A comparison of the binge eating scale, questionnaire for eating and weight patterns-revised, and eating disorder examination questionnaire with instructions with the eating disorder examination in the assessment of binge eating disorder and its symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 36, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| STUDY PERIOD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment | Baseline | Post-allocation | ||

| TIMEPOINT | T-1 | T0 | T1 | T2 |

| ENROLMENT: | ||||

| Eligibility screen | X | |||

| Informed consent | X | |||

| Allocation | X | |||

| INTERVENTIONS: | ||||

| Interventiongroup |  | |||

| Delayed waitlist group | ||||

| ASSESSMENTS: | ||||

| Demographic/clinical data | X | |||

| EDE-Q | X | X | X | |

| BES | X | X | X | |

| MAAS | X | X | X | |

| DERS | X | X | X | |

| BMI | X | X | X | |

| IES-2 | X | X | X | |

| DASS-21 | X | X | X | |

| Acceptability | Following each module | |||

| User feedback | X | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cruz, T.; Ferreira, T.B.; Safer, D.L.; Duarte, C.; Martins, M.V. A Smartphone Application Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills for Binge Eating Episodes: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141749

Cruz T, Ferreira TB, Safer DL, Duarte C, Martins MV. A Smartphone Application Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills for Binge Eating Episodes: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141749

Chicago/Turabian StyleCruz, Telma, Tiago B. Ferreira, Debra L. Safer, Cristiana Duarte, and Mariana V. Martins. 2025. "A Smartphone Application Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills for Binge Eating Episodes: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141749

APA StyleCruz, T., Ferreira, T. B., Safer, D. L., Duarte, C., & Martins, M. V. (2025). A Smartphone Application Based on Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills for Binge Eating Episodes: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare, 13(14), 1749. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141749