Assessing Stress and Shift Quality in Nursing Students: A Pre- and Post-Shift Survey Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Description of the Survey Instrument

3. Domains Tested

3.1. Tasks

3.2. Internal Environmental Factors

3.3. Organizational Factors

3.4. External Environment

3.5. Stress Coping Strategies

3.6. Overall Satisfaction

3.7. Definitions

3.8. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation

4.3. Paired T Tests

4.4. Unit Type

4.5. Collegiality

4.6. Linear Regression

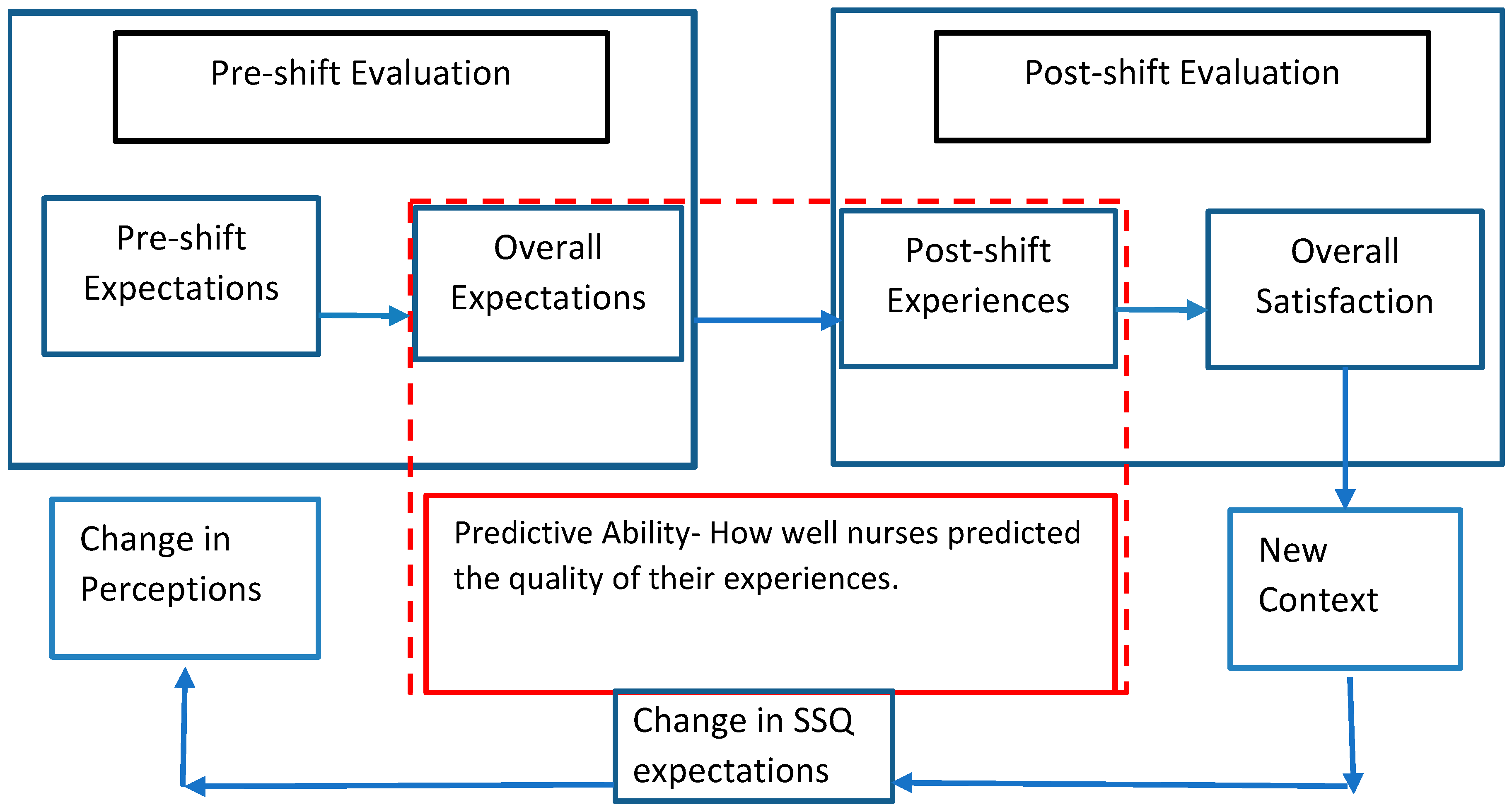

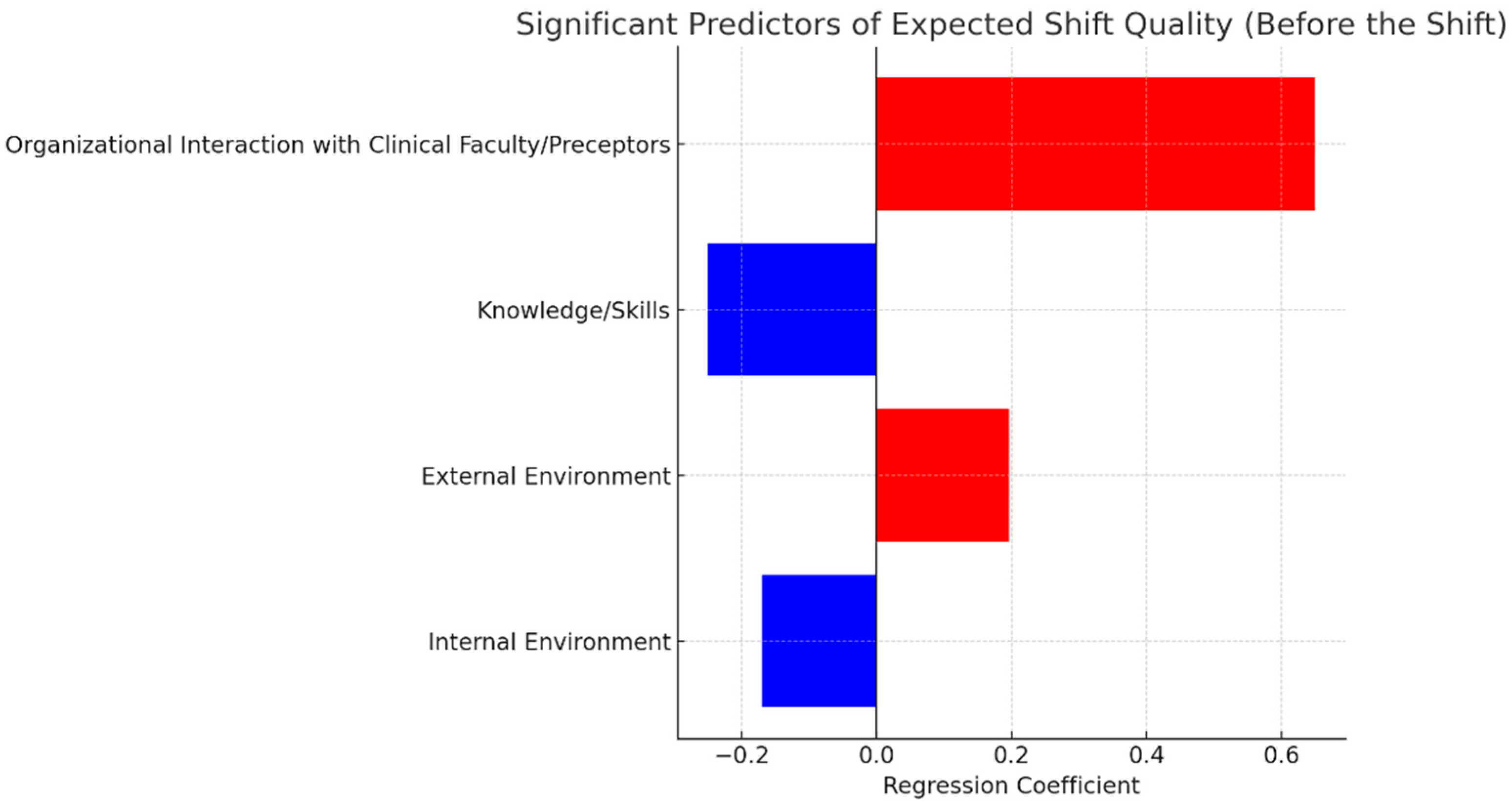

- The first model used pre-shift independent variables to predict pre-shift overall shift quality.

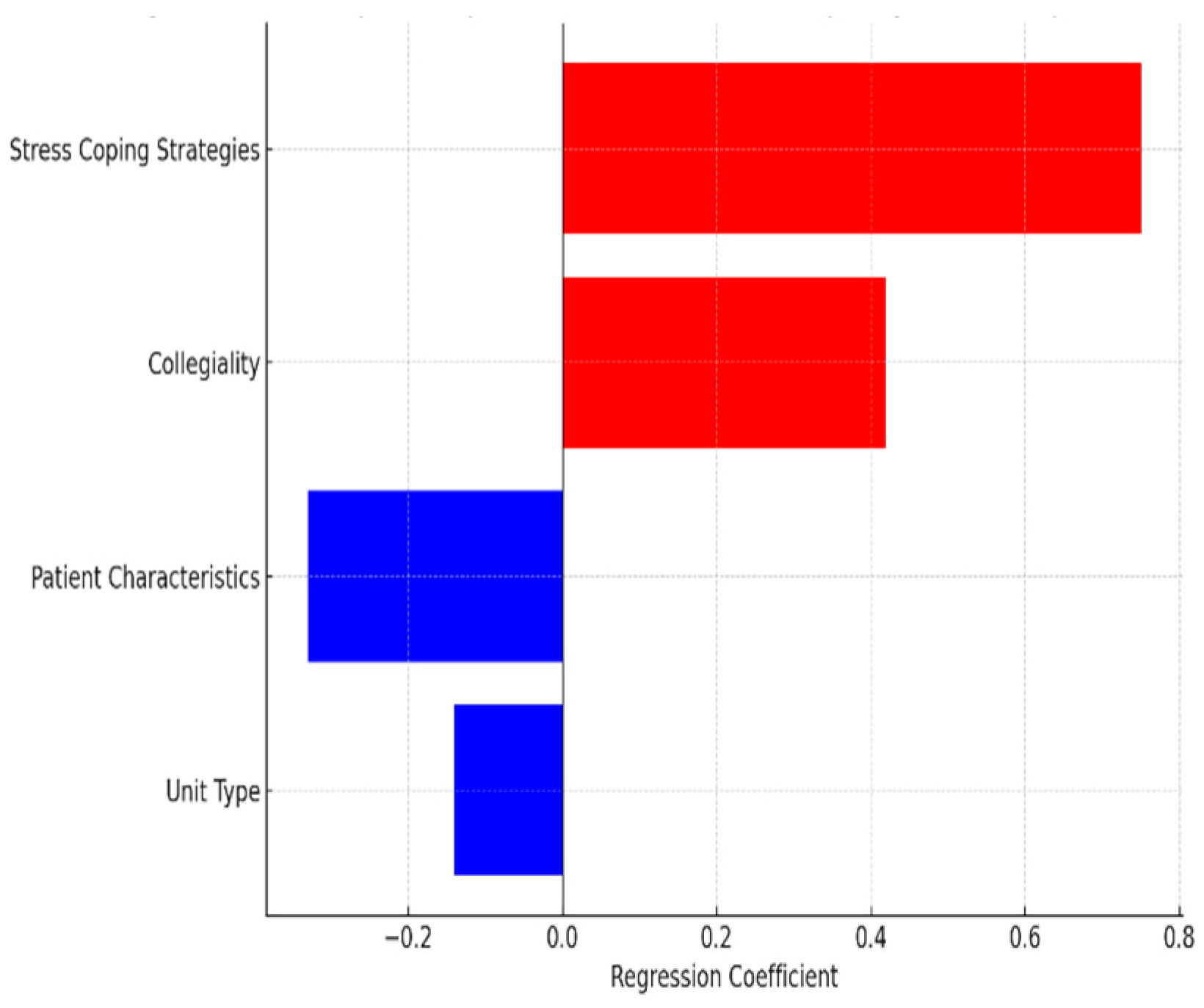

- The second model used post-shift independent variables to predict post-shift overall shift quality.

- The third model used pre-shift independent variables to predict post-shift overall shift quality to determine whether the students’ expectations could accurately predict their actual shift experience.

5. Discussion

5.1. Pre-Shift Perceptions: Structured and Interconnected Expectations

5.2. Post-Shift Realities: Fragmentation of Perceptions

5.3. Role of Organizational Interaction and Faculty Support

5.4. Coping Strategies and Psychological Flexibility

5.5. Implications for Training and Practice

5.6. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartlett, M.L.; Taylor, H.; Nelson, J.D. Comparison of Mental Health Characteristics and Stress Between Baccalaureate Nursing Students and Non-Nursing Students. J. Nurs. Educ. 2016, 55, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornine, A. Reducing Nursing Student Anxiety in the Clinical Setting: An Integrative Review. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2020, 41, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.-S.; Hasson, F. Resilience, Stress, and Psychological Well-Being in Nursing Students: A Systematic Review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 90, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido-Martos, M.; Augusto-Landa, J.M.; Lopez-Zafra, E. Sources of Stress in Nursing Students: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.d.L.; Abreu, L.C.d.; Ramos, J.L.S.; Castro, C.F.D.d.; Smiderle, F.R.N.; Santos, J.A.d.; Bezerra, I.M.P. Influence of Burnout on Patient Safety: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2019, 55, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Active Minds Active Minds’ Student Mental Health Survey—Active Minds. Available online: https://activeminds.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Student-Survey-Infographic.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Lu, S.A.; Schumacher, R.E.; Nemshak, M.; Seagull, F.J. Identifying, Developing, and Quantifying Single-Day Quality Measures within the Neonatal ICU. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2013, 57, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Fatemi, Y.; Ali, D.; Hamasha, M.; Hamasha, S. Investigating Frontline Nurse Stress: Perceptions of Job Demands, Organizational Support, and Social Support During the Current COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 839600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Fatemi, Y.; Hamasha, M.; Modi, S. The Cost of Frontline Nursing: Investigating Perception of Compensation Inadequacy During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, S. Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Among Undergraduate Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Their Use of Mental Health Services. Innov. High Educ. 2021, 46, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, L.M.; Burmeister, E.; Clayton, S.; Dalais, C.; Gardner, G. The Impact of Nursing Rounds on the Practice Environment and Nurse Satisfaction in Intensive Care: Pre-Test Post-Test Comparative Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cole, A.; Ali, H.; Ahmed, A.; Hamasha, M.; Jordan, S. Identifying Patterns of Turnover Intention Among Alabama Frontline Nurses in Hospital Settings During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 1783–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carayon, P.; Gurses, A.P. Nursing Workload and Patient Safety—A Human Factors Engineering Perspective. In Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses; Hughes, R.G., Ed.; Advances in Patient Safety; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Karsh, B.; Holden, R.J.; Alper, S.J.; Or, C.K.L. A Human Factors Engineering Paradigm for Patient Safety: Designing to Support the Performance of the Healthcare Professional. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, i59–i65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, R.J.; Carayon, P.; Gurses, A.P.; Hoonakker, P.; Hundt, A.S.; Ozok, A.A.; Rivera-Rodriguez, A.J. SEIPS 2.0: A Human Factors Framework for Studying and Improving the Work of Healthcare Professionals and Patients. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 1669–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, R.J.; Scanlon, M.C.; Patel, N.R.; Kaushal, R.; Escoto, K.H.; Brown, R.L.; Alper, S.J.; Arnold, J.M.; Shalaby, T.M.; Murkowski, K.; et al. A Human Factors Framework and Study of the Effect of Nursing Workload on Patient Safety and Employee Quality of Working Life. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011, 20, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Oetelaar, W.F.J.M.; van Stel, H.F.; van Rhenen, W.; Stellato, R.K.; Grolman, W. Balancing Nurses’ Workload in Hospital Wards: Study Protocol of Developing a Method to Manage Workload. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slatore, C.G.; Hansen, L.; Ganzini, L.; Press, N.; Osborne, M.L.; Chesnutt, M.S.; Mularski, R.A. Communication by Nurses in the Intensive Care Unit: Qualitative Analysis of Domains of Patient-Centered Care. Am. J. Crit. Care 2012, 21, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birmingham, P.; Buffum, M.D.; Blegen, M.A.; Lyndon, A. Handoffs and Patient Safety: Grasping the Story and Painting a Full Picture. West J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 37, 1458–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-H.; Phan, P.H.; Dorman, T.; Weaver, S.J.; Pronovost, P.J. Handoffs, Safety Culture, and Practices: Evidence from the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagerström, L.; Kinnunen, M.; Saarela, J. Nursing Workload, Patient Safety Incidents and Mortality: An Observational Study from Finland. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Cole, A.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Ho, T. Perspectives of Nursing Homes Staff on the Nature of Residents-Initiated Call Lights. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020, 6, 2377960820903546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Li, H. Use of Notification and Communication Technology (Call Light Systems) in Nursing Homes: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e16252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Li, H. Notification and Communication Technology: An Observational Study of Call Light Systems in Nursing Homes. Res. Sq. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L. Interprofessional Collaboration in the ICU: How to Define? Nurs. Crit. Care 2011, 16, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.H.; Patrician, P.A. Measuring Organizational Traits of Hospitals: The Revised Nursing Work Index. Nurs. Res. 2000, 49, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, R.L.; Shamliyan, T.; Mueller, C.; Duval, S.; Wilt, T.J. Nurse Staffing and Quality of Patient Care. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. (Full Rep.) 2007, 151, 1–115. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, D.B.; Boudreau, P. Impacts of Shift Work on Sleep and Circadian Rhythms. Pathol. Biol. 2014, 62, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, T.S.; Moreira, C.Z.; Guo, J.; Noce, F. Effects of a 12-Hour Shift on Mood States and Sleepiness of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Nurses. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2017, 51, e03202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Cole, A.; Ahmed, A.; Hamasha, S.; Panos, G. Major Stressors and Coping Strategies of Frontline Nursing Staff During the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2020 (COVID-19) in Alabama. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 2057–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kock, J.H.; Latham, H.A.; Leslie, S.J.; Grindle, M.; Munoz, S.-A.; Ellis, L.; Polson, R.; O’Malley, C.M. A Rapid Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers: Implications for Supporting Psychological Well-Being. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fteropoulli, T.; Kalavana, T.V.; Yiallourou, A.; Karaiskakis, M.; Koliou Mazeri, M.; Vryonides, S.; Hadjioannou, A.; Nikolopoulos, G.K. Beyond the Physical Risk: Psychosocial Impact and Coping in Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, J.B.; Helmreich, R.L.; Neilands, T.B.; Rowan, K.; Vella, K.; Boyden, J.; Roberts, P.R.; Thomas, E.J. The Safety Attitudes Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties, Benchmarking Data, and Emerging Research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, C. Stress, Coping and Burn-out in Nursing Students. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. ix, 604. ISBN 978-0-7167-2626-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, S.; Cowburn, J. Emotional Labour and Stress within Mental Health Nursing. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 12, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilden, V.P.; Tilden, S.; Benner, P. From Novice to Expert, Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Res. Nurs. Health 1985, 8, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, C.G. Using The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice (2008) as a Framework for Curriculum Revision. J. Prof. Nurs. 2011, 27, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealer, M.; Conrad, D.; Evans, J.; Jooste, K.; Solyntjes, J.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Resilience Training Program for Intensive Care Unit Nurses. Am. J. Crit. Care 2014, 23, e97–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, V.; Lambert, C. Nurses’ Workplace Stressors and Coping Strategies. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2008, 14, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-23747-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Thomas, M.R.; Shanafelt, T.D. Systematic Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Other Indicators of Psychological Distress Among U.S. and Canadian Medical Students. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic Variable | Number of Participants (n = 304), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean | 21.86 |

| Sex | |

| 42 (14) |

| 262 (86) |

| Semester | |

| 103 (34) |

| 90 (29) |

| 111 (37) |

| Shift Type | |

| 105 (35) |

| 94 (30) |

| 105 (35) |

| Clinical Faculty | |

| 146 (48) |

| 158 (52) |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit type (1) | 1 | 0.12 * | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.20 ** | 0.02 | −0.14 * | 0.03 | 0.13 * | −0.00 | 0.04 |

| Collegiality (2) | 1 | 0.19 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.14 * | 0.04 | 0.12 * | |

| Knowledge/skills (3) | 1 | 0.41 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.09 | 0.35 ** | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.17 ** | −0.04 | ||

| Feeling comfortable with the tasks assigned (4) | 1 | 0.37 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.14 * | 0.10 | 0.00 | |||

| Patient characteristics (5) | 1 | 0.17 ** | 0.12 * | 0.25 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.036 | 0.20 ** | ||||

| Internal environment (6) | 1 | 0.30 * | 0.08 | 0.14 * | 0.00 | 0.03 | |||||

| Organizational interaction with clinical training faculty/preceptor (7) | 1 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.21 ** | 0.14 * | ||||||

| External environment (8) | 1 | 0.44 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.07 | |||||||

| Stress coping strategies (9) | 1 | 0.16 ** | −0.17 ** | ||||||||

| Overall (10) | 1 | −0.12 * | |||||||||

| Age (11) | 1 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit type (1) | 1 | 0.02 | −0.16 ** | −0.06 | −0.11 | 0.0 | 0.03 | 0.12 * | 0.01 | −0.12 * | −0.08 |

| Collegiality (2) | 1 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.19 ** | −0.01 | |

| Knowledge/skills (3) | 1 | 0.07 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.06 | ||

| Feeling comfortable with the tasks assigned (4) | 1 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.25 ** | −0.09 | 0.14 * | 0.08 | 0.07 | |||

| Patient characteristics (5) | 1 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.11 | 0.06 | ||||

| Internal environment (6) | 1 | −0.13 * | −0.17 ** | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.05 | |||||

| Organizational interaction with the clinical training faculty/preceptor (7) | 1 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.12 | ||||||

| External environment (8) | 1 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |||||||

| Stress-coping strategies (9) | 1 | 0.22 ** | 0.06 | ||||||||

| Overall (10) | 1 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| Age (11) | 1 |

| Variable | T Statistics | Prior Mean | Post Mean | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit type | −4.32 | 2.73 | 3.17 | <0.001 * |

| Collegiality | −9.82 | 2.49 | 2.96 | <0.001 * |

| Knowledge/skills | −6.12 | 2.39 | 3.00 | <0.001 * |

| Feeling comfortable with the tasks assigned | 19.35 | 3.69 | 3.00 | <0.001 * |

| Patient characteristics | 0.87 | 3.20 | 3.15 | 0.38 |

| Internal environment | 14.96 | 3.57 | 2.94 | <0.001 * |

| Organizational interaction with the clinical training faculty/preceptors | 25.74 | 4.00 | 2.99 | <0.001 * |

| External environment | 0.1538 | 2.97 | 2.96 | 0.81 |

| Stress-coping strategies | 14.55 | 3.46 | 3.03 | <0.001 * |

| Overall | 12.22 | 4.14 | 3.03 | <0.001 * |

| Variable | Coef | STD Err | T | [0.025] | [0.975] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.47 | 0.60 | 2.48 | 0.014 | 0.305 | 2.65 * |

| Unit type | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.67 | −0.06 | 0.09 |

| Collegiality | −0.078 | 0.08 | −0.96 | 0.34 | −0.24 | 0.08 |

| Knowledge/skills | −0.25 | 0.04 | −6.14 | 0.00 | −0.34 | −0.17 * |

| Feeling comfortable with the tasks assigned | 0.22 | 0.11 | 1.93 | 0.05 | −0.00 | 0.45 |

| Patient characteristics | −0.02 | 0.061 | −0.39 | 0.70 | −0.14 | 0.098 |

| Internal environment | −0.17 | 0.08 | −2.027 | 0.04 | −0.32 | −0.01 * |

| Organizational interaction with clinical training faculty/preceptors | 0.65 | 0.115 | 5.69 | 0.00 | 0.43 | 0.88 * |

| External environment | 0.19 | 0.03 | 5.89 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 0.26 * |

| Stress-coping strategies | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.88 | −0.24 | 0.28 |

| Variable | Coef | STD Err | T | [0.025] | [0.975] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.83 | 1.36 | 0.61 | 0.54 | −1.84 | 3.51 |

| Unit type | −0.14 | 0.05 | −2.60 | 0.01 | −0.25 | −0.03 * |

| Collegiality | 0.42 | 0.13 | 3.29 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.68 * |

| Knowledge/skills | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.88 | 0.38 | −0.16 | 0.06 |

| Feeling comfortable with the tasks assigned | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.76 | 0.44 | −0.22 | 0.50 |

| Patient characteristics | −0.33 | 0.4 | −2.28 | 0.02 | −0.61 | −0.05 * |

| Internal environment | −0.25 | 0.15 | −1.62 | 0.10 | −0.55 | 0.05 |

| Organizational interaction with the clinical training faculty/preceptors | 0.23 | 0.14 | 1.62 | 0.10 | −0.05 | 0.51 |

| External environment | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.28 | 0.77 | −0.22 | 0.16 |

| Stress-coping strategies | 0.75 | 0.21 | 3.54 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 1.17 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, H.; Fatemi, Y. Assessing Stress and Shift Quality in Nursing Students: A Pre- and Post-Shift Survey Approach. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141741

Ali H, Fatemi Y. Assessing Stress and Shift Quality in Nursing Students: A Pre- and Post-Shift Survey Approach. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141741

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Haneen, and Yasin Fatemi. 2025. "Assessing Stress and Shift Quality in Nursing Students: A Pre- and Post-Shift Survey Approach" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141741

APA StyleAli, H., & Fatemi, Y. (2025). Assessing Stress and Shift Quality in Nursing Students: A Pre- and Post-Shift Survey Approach. Healthcare, 13(14), 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141741