Older People at Risk of Suicide: A Local Study During the COVID-19 Confinement Period

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection and Procedure

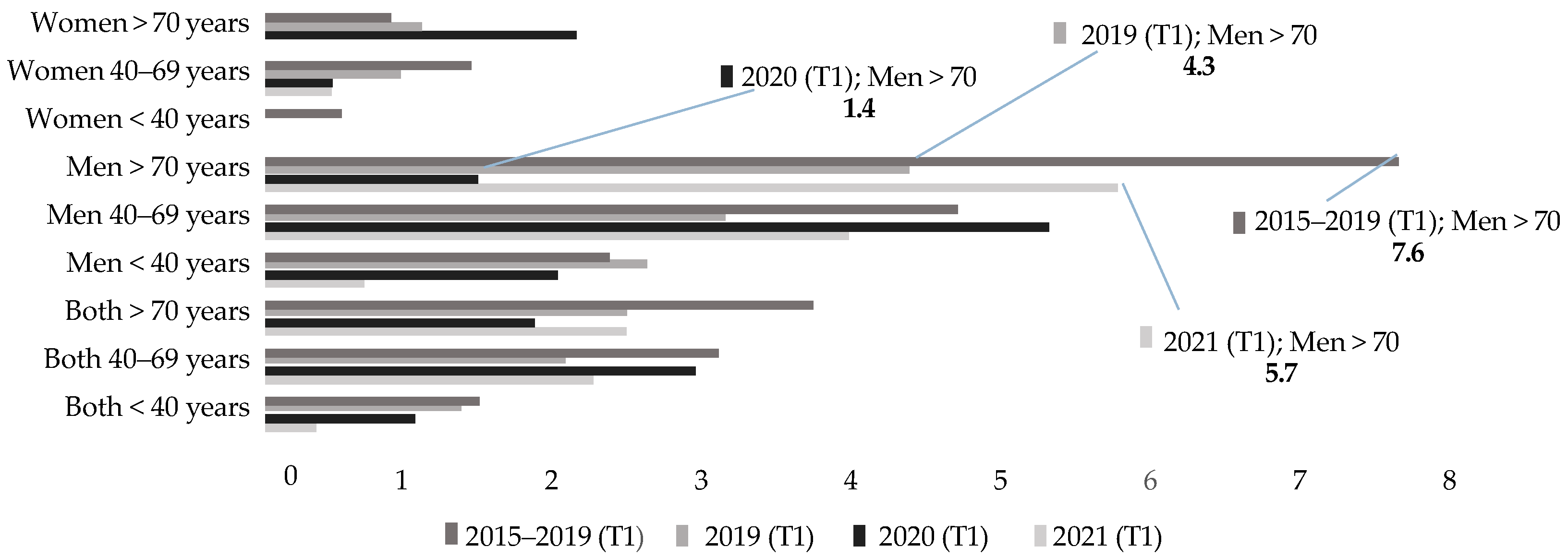

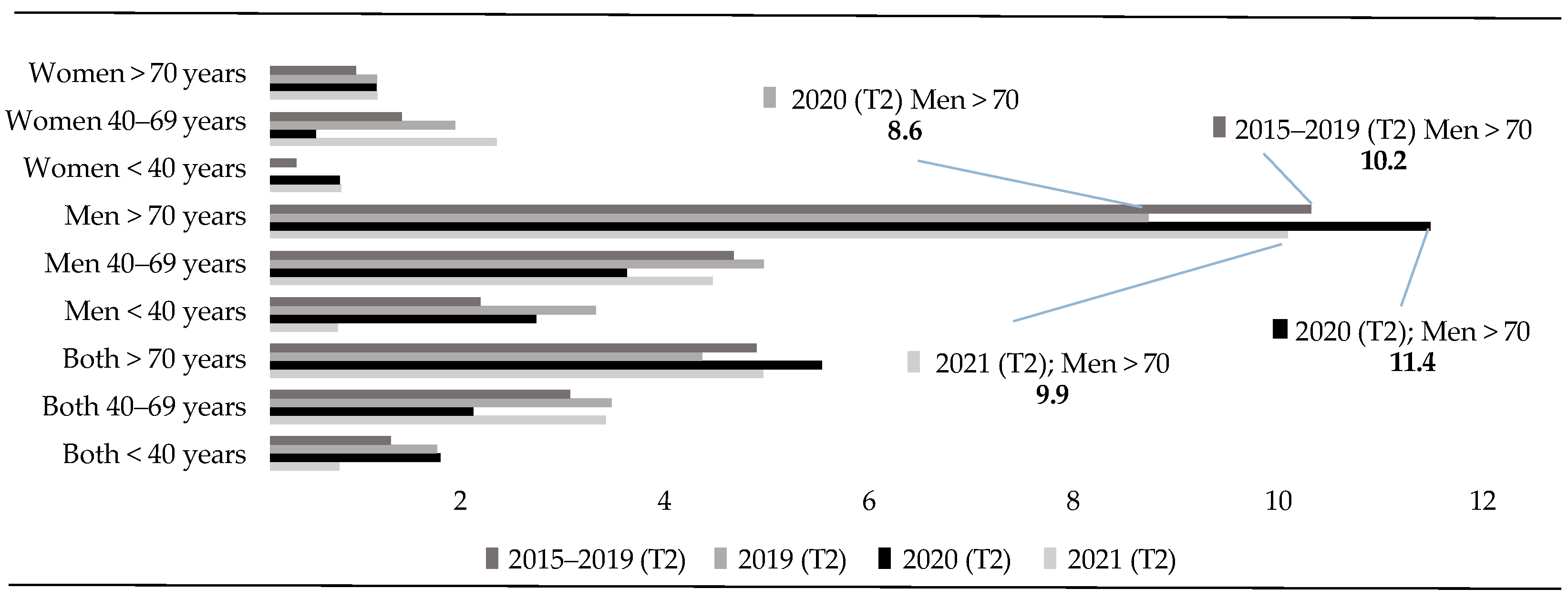

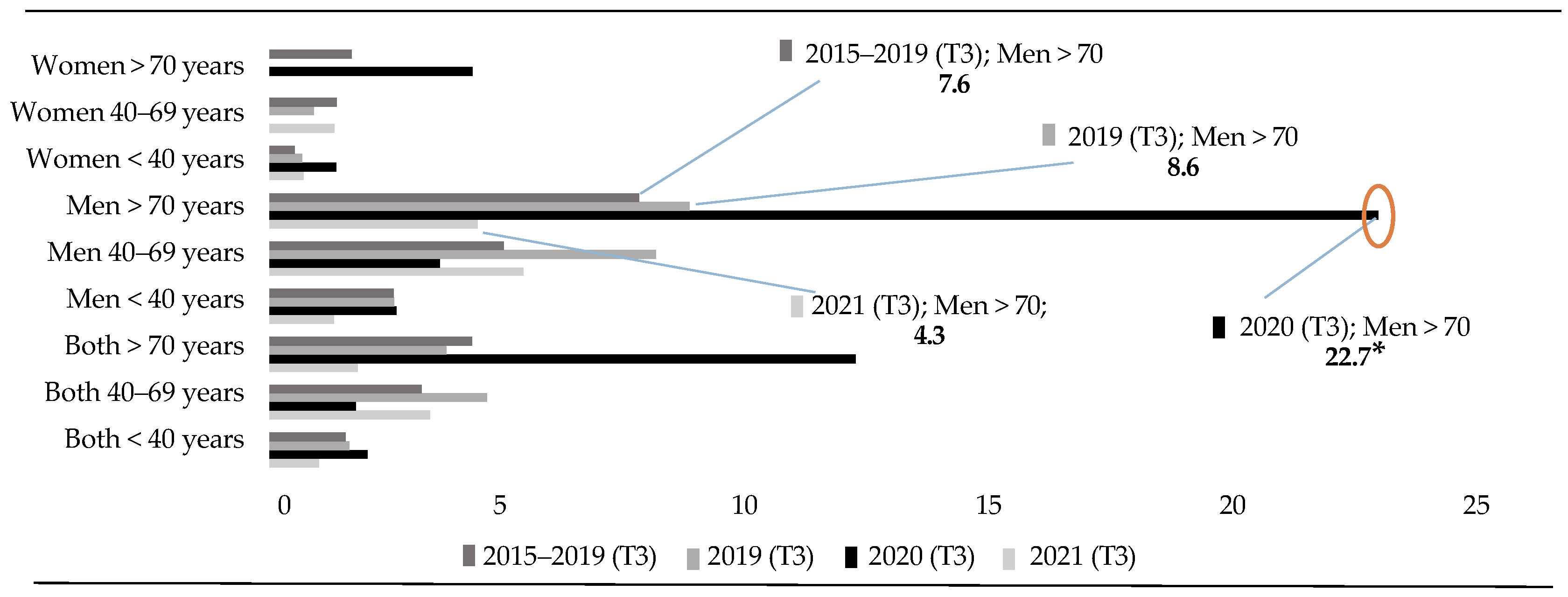

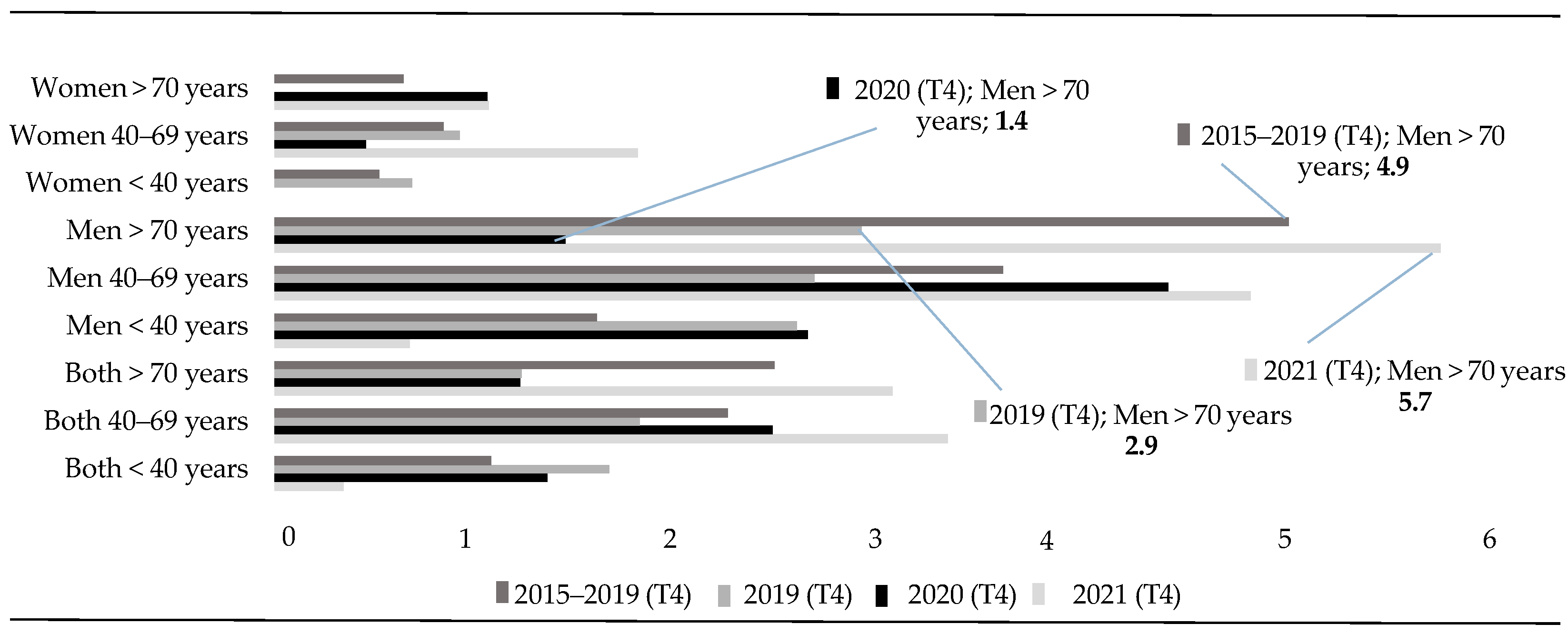

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wand, A.P.F.; Peisah, C.; Draper, B.; Brodaty, H. Understanding self-harm in older people: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Conwell, Y. Issues in research on aging and suicide. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crestani, C.; Masotti, V.; Corradi, N.; Schirripa, M.L.; Cecchi, R. Suicide in the elderly: A 37-years retrospective study. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2019, 90, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M. Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ 2019, 364, l94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Ageing and Health. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. How’s Life? 2024 Well-Being and Resilience in Times of Crisis; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crivelli, L.; Palmer, K.; Calandri, I.; Guekht, A.; Beghi, E.; Carroll, W.; Frontera, J.; García-Azorín, D.; Westenberg, E.; Winkler, A.S.; et al. Changes in cognitive functioning after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, 1047–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrottelli, A.; Sansone, N.; Giordano, G.M.; Caporusso, E.; Giuliani, L.; Melillo, A.; Pezzella, P.; Bucci, P.; Mucci, A.; Galderisi, S. Cognitive Impairment after Post-Acute COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Kapczinski, F.; de Azevedo Cardoso, T.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Rosa, A.R.; Mota, J.C.; De Boni, R.B. The assessment of lifestyle changes during the COVID-19 pandemic using a multidimensional scale. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2021, 14, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Joiner, T.E. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebrasseur, A.; Fortin-Bédard, N.; Lettre, J.; Raymond, E.; Bussières, E.L.; Lapierre, N.; Faieta, J.; Vincent, C.; Duchesne, L.; Ouellet, M.C.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Older Adults: Rapid Review. JMIR Aging 2021, 4, e26474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Hou, W.; Niu, H.; Ma, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L. Comparing the centrality symptoms of major depressive disorder samples across junior high school students, senior high school students, college students and elderly adults during city lockdown of COVID-19 pandemic-A network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 324, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amicucci, G.; Salfi, F.; D’Atri, A.; Viselli, L.; Ferrara, M. The Differential Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Sleep Quality, Insomnia, Depression, Stress, and Anxiety among Late Adolescents and Elderly in Italy. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Zhong, B.L.; Chiu, H.F. Prevalence of depressive symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, L.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; García-Portilla, M.P.; Sáiz, P.A.; Lacasa, C.M.; Dal Santo, F.; González-Blanco, L.; Bobes-Bascarán, M.T.; García, M.V.; Vázquez, C.Á.; et al. Early psychological impact of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown in a large Spanish sample. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 020505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorsson, S.; Runeson, B.; Skoog, I.; Ostling, S.; Waern, M. Attempted suicide in the elderly: Characteristics of suicide attempters 70 years and older and a general population comparison group. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 18, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troya, M.I.; Babatunde, O.; Polidano, K.; Bartlam, B.; McCloskey, E.; Dikomitis, L.; Chew-Graham, C.A. Self-harm in older adults: Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 214, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Annual Report on the National Health System of Spain 2020–2021. 2022. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/sisInfSanSNS/tablasEstadisticas/InfAnualSNS2020_21/Annual_Report_2020_21.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Pirkis, J.; John, A.; Shin, S.; DelPozo-Banos, M.; Arya, V.; Analuisa-Aguilar, P.; Appleby, L.; Arensman, E.; Bantjes, J.; Baran, A.; et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: An interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J.; Gunnell, D.; Shin, S.; Del Pozo-Banos, M.; Arya, V.; Aguilar, P.A.; Appleby, L.; Arafat, S.M.Y.; Arensman, E.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; et al. Suicide numbers during the first 9-15 months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-existing trends: An interrupted time series analysis in 33 countries. Eclinicalmedicine 2022, 51, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, B.; Subedi, K.; Acharya, P.; Ghimire, S. Association between COVID-19 pandemic and the suicide rates in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Okamoto, S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, V.; Cherian, A.V.; Vijayakumar, L. Rising incidence and changing demographics of suicide in India: Time to recalibrate prevention policies? Asian J. Psychiatr. 2022, 69, 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogalska, A.; Syrkiewicz-Świtała, M. COVID-19 and Mortality, Depression, and Suicide in the Polish Population. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 854028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.Y.; Tang, S.L.; Ma, S.L.; Guan, W.J.; Xu, X.; Xu, H.; Xu, Y.S.; Xu, Y.J.; Lin, L.F. Trends of injury mortality during the COVID-19 period in Guangdong, China: A population-based retrospective analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ornell, F.; Benzano, D.; Borelli, W.V.; Narvaez, J.C.M.; Moura, H.F.; Passos, I.C.; Sordi, A.O.; Schuch, J.B.; Kessler, F.H.P.; Scherer, J.N.; et al. Differential impact on suicide mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2022, 44, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana, J.D.Y.; de Souza, M.L.P. Excess suicides in Brazil: Inequalities according to age groups and regions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, V.; Elices, M.; Vilagut, G.; Vieta, E.; Blanch, J.; Laborda-Serrano, E.; Prat, B.; Colom, F.; Palao, D.; Alonso, J. Suicide-related thoughts and behavior and suicide death trends during the COVID-19 in the general population of Catalonia, Spain. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 56, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Torre-Luque, A.; Pemau, A.; Perez-Sola, V.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. Suicide mortality in Spain in 2020: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Span. J. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 16, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Alés, G.; López-Cuadrado, T.; Morrison, C.; Keyes, K.; Susser, E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide mortality in Spain: Differences by sex and age. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 329, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Amores, I.; Cuadrado-Gordillo, I.; Martín-Mora-Parra, G. Suicide and Health Crisis in Extremadura: Impact of Confinement during COVID-19. Trauma Care 2021, 1, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/332070/9789240005105-eng.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- John, A.; Eyles, E.; Webb, R.T.; Okolie, C.; Schmidt, L.; Arensman, E.; Hawton, K.; O’Connor, R.C.; Kapur, N.; Moran, P.; et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: Update of living systematic review. F1000Research 2020, 9, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coley, R.L.; Baum, C.F. Trends in mental health symptoms, service use, and unmet need for services among US adults through the first 8 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Behav. Med. 2022, 12, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliadis, H.M.; Léon, C.; du Roscoät, E.; Husky, M.M. Suicidal ideation and mental health care: Predisposing, enabling and need factors associated with general and specialist mental health service use in France. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69, 1285–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliadis, H.M.; Spagnolo, J.; Fleury, M.J.; Gouin, J.P.; Roberge, P.; Bartram, M.; Grenier, S.; Shen-Tu, G.; Vena, J.E.; Wang, J. Mental health service use and associated predisposing, enabling and need factors in community living adults and older adults across Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Amores, I.; Cuadrado-Gordillo, I.; Martín-Mora-Parra, G. Health Service Protection vis-à-vis the Detection of Psychosocial Risks of Suicide during the Years 2019–2021. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrieri, M.; Rucci, P.; Amendola, D.; Bonizzoni, M.; Cerveri, G.; Colli, C.; Dragogna, F.; Ducci, G.; Elmo, M.G.; Ghio, L.; et al. Emergency Psychiatric Consultations During and After the COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. A Multicentre Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 697058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerónimo, M.A.; Piñar, S.; Samos, P.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Bellsolà, M.; Sabaté, A.; León, J.; Aliart, X.; Martín, L.M.; Aceña, R.; et al. Suicidal attempt and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to previous years. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud. Ment. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardelli, I.; Sarubbi, S.; Rogante, E.; Cifrodelli, M.; Erbuto, D.; Innamorati, M.; Lester, D.; Pompili, M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide ideation and suicide attempts in a sample of psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 303, 114072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibert, T.; Schroeder, M.W.; Perkins, A.J.; Park, S.; Batista-Malat, E.; Head, K.J.; Bakas, T.; Boustani, M.; Fowler, N.R. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Older Primary Care Patients and Their Family Members. J. Aging Res. 2022, 2022, 6909413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, J.S.; Shah, S.B.; Du, C.; Li, S.X.; Lin, Z.; Krumholz, H.M. Suicide Deaths During the COVID-19 Stay-at-Home Advisory in Massachusetts, March to May 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2034273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radeloff, D.; Papsdorf, R.; Uhlig, K.; Vasilache, A.; Putnam, K.; von Klitzing, K. Trends in suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in a major German city. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2021, 30, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzai, T.; Fukui, K.; Ito, T.; Ito, Y.; Takahashi, K. Excess Mortality From Suicide During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic Period in Japan: A Time-Series Modeling Before the Pandemic. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, P.; Mehlum, L. National observation of death by suicide in the first 3 months under COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 2021, 143, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, A.M. The short-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on suicides in Korea. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deisenhammer, E.A.; Kemmler, G. Decreased suicide numbers during the first 6 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderon-Anyosa, R.J.C.; Kaufman, J.S. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown policy on homicide, suicide, and motor vehicle deaths in Peru. Prev. Med. 2021, 143, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelezelyte, O.; Dragan, M.; Grajewski, P.; Kvedaraite, M.; Lotzin, A.; Skrodzka, M.; Nomeikaite, A.; Kazlauskas, E. Factors associated with suicide ideation in Lithuania and Poland amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Crisis 2022, 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, J.P.; Smith, M.M.; Sherry, S.B.; Hewitt, P.L.; Stewart, S.H. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López Steinmetz, L.C.; Fong, S.B.; Godoy, J.C. Suicidal risk and impulsivity-related traits among young Argentinean college students during a quarantine of up to 103-day duration: Longitudinal evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2021, 51, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Su, S.; Jiang, Z.; Guo, S.; Lu, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, P.; Que, J.; Shi, L.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Mental Health Symptoms and Suicidal Behavior Among University Students in Wuhan, China During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 695017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichter, B.; Stein, M.B.; Norman, S.B.; Hill, M.L.; Straus, E.; Haller, M.; Pietrzak, R.H. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of suicidal behavior in US military veterans: Results from the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2021, 82, 35870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinyor, M.; Zaheer, R.; Webb, R.T.; Knipe, D.; Eyles, E.; Higgins, J.P.T.; McGuinness, L.; Schmidt, L.; Macleod-Hall, C.; Dekel, D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Risk of Suicidal and Self-Harm Thoughts and Behaviour: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2022, 67, 812–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguchi, A.; Nomura, S.; Gilmour, S.; Harada, N.; Sakamoto, H.; Ueda, P.; Yoneoka, D.; Tanoue, Y.; Kawashima, T.; Hayashi, T.I.; et al. Suicide by gender and 10-year age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic vs previous five years in Japan: An analysis of national vital statistics. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 305, 114173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouillet, A.; Martin, D.; Pontais, I.; Caserio-Schönemann, C.; Rey, G. Reactive surveillance of suicides during the COVID-19 pandemic in France, 2020 to March 2022. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2023, 32, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calati, R.; Gentile, G.; Fornaro, M.; Madeddu, F.; Tambuzzi, S.; Zoja, R. Suicide and homicide before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Milan, Italy. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 12, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canetto, S.S.; Sakinofsky, I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1998, 28, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alicandro, G.; Malvezzi, M.; Gallus, S.; La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E.; Bertuccio, P. Worldwide trends in suicide mortality from 1990 to 2015 with a focus on the global recession time frame. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.-S.; Stuckler, D.; Yip, P.; Gunnell, D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: Time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ 2013, 347, f5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanchan, T.; Menon, A.; Menezes, R.G. Methods of choice in completed suicides: Gender differences and review of literature. J. Forensic. Sci. 2009, 54, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, L.; Brovelli, S.; Bourquin, C. The gender paradox in suicide: Some explanations and much uncertainty. Rev. Med. Suisse 2021, 17, 1265–1267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schrijvers, D.L.; Bollen, J.; Sabbe, B.G. The gender paradox in suicidal behavior and its impact on the suicidal process. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommersbach, T.J.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Petrakis, I.L.; Rhee, T.G. Why are women more likely to attempt suicide than men? Analysis of lifetime suicide attempts among US adults in a nationally representative sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 311, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroebe, W.; Stroebe, M.S. Bereavement and Health: The Psychological and Physical Consequences of Partner Loss; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio Herrera, R. Un estudio sobre la soledad en las personas mayores: Entre estar solo y sentirse solo. Rev. Multidiscip. Gerontol. 2001, 11, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Edelman, L.S.; Tracy, E.L.; Demiris, G.; Sward, K.A.; Donaldson, G.W. Loneliness as a mediator of the impact of social isolation on cognitive functioning of chinese older adults. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Pavon, D.; Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Lavie, C.J. Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: Special focus in older people. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitrago Ramírez, F.; Ciurana Misol, R.; Fernández Alonso, M.D.C.; Tizón, J.L. Pandemia de la COVID-19 y salud mental: Reflexiones iniciales desde la atención primaria de salud española. Aten. Primaria 2021, 53, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, D.; Kosagisharaf, J.R.; Sathyanarayana Rao, T.S. ‘The dual pandemic’ of suicide and COVID-19: A biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, I.-T.; Fu-Tsung Shaw, F.; Hsu, W.-Y.; Liu, G.-Y.; Kuan, C.-I.; Gunnell, D.; Chang, S.-S. “I can’t see an end in sight.” How the COVID-19 pandemic may influence suicide risk. Crisis 2022, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Port, M.S.; Lake, A.M.; Hoyte-Badu, A.M.; Rodriguez, C.L.; Chowdhury, S.J.; Goldstein, A.; Murphy, S.; Cornette, M.; Gould, M.S. Perceived impact of COVID-19 among callers to the national suicide -prevention lifeline. Crisis 2022, 44, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, T. España ya es el Segundo País de Europa en Incidencia de Coronavirus. La voz de Galicia. 30 de julio de 2020. Available online: https://www.lavozdegalicia.es/noticia/sociedad/2020/07/29/espana-segundo-pais-europa-incidencia-coronavirus/00031596045845238485350.htm (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chishti, P.; Stone, D.H.; Corcoran, P.; Williamson, E.; Petridou, E.; Eurosave Working Group. Suicide mortality in the European Union. Eur. J. Public Health 2003, 13, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giner, L.; Guija, J.A. Número de suicidios en España: Diferencias entre los datos del Instituto Nacional de Estadística y los aportados por los Institutos de Medicina Legal. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2014, 7, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbería, E.; Xifró, A.; Arimany-Manso, J. Impacto beneficioso de la incorporación de las fuentes forenses a las estadísticas de mortalidad. Rev. Esp. Med. Leg. 2017, 43, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J.; Scheftner, W.A.; Fogg, L.; Clark, D.C.; Young, M.A.; Hedeker, D.; Gibbons, R. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 1189–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.E.; Al Zubayer, A.; Al Mazid Bhuiyan, M.R.; Jobe, M.C.; Ahsan Khan, M.K. Suicidal behaviors and suicide risk among Bangladeshi people during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online cross-sectional survey. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradera, M.; Ouchi, D.; Prat, O.; Morros, R.; Martin-Fumadó, C.; Palao, D.; Cardoner, N.; Campillo, M.T.; Pérez-Solà, V.; Pontes, C. Can routine Primary Care Records Help in Detecting Suicide Risk? A Population-Based Case-Control Study in Barcelona. Arch Suicide Res. 2022, 26, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luoma, J.B.; Pearson, J.L. Suicide and marital status in the United States, 1991-1996: Is widowhood a risk factor? Am. J. Public Health 2002, 92, 1518–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guil, J. Intento de suicidio antes y durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Estudio comparativo desde el servicio de urgencias. Fam. Med. 2023, 49, e101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conwell, Y.; Van Orden, K.; Caine, E.D. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 34, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Statistics [INE]. Deaths by Suicide in Spain. 2024. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/mortalidad/docs/DefunSuicidio2022-2024_NOTA__TEC.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Institute for the Elderly and Social Services (IMSERSO). Social Services for Older People in Spain. December 2023. Available online: https://imserso.es/el-imserso/documentacion/estadisticas/servicios-sociales-dirigidos-a-personas-mayores-en-espana-diciembre-2023 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Ponce de León, L.P.; Lévy, J.P.; Fernández, T.; Ballesteros, S. Modeling Active Aging and Explicit Memory: An Empirical Study. Health Soc. Work 2015, 40, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joiner, T.E. Why People Die by Suicide; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky, E.D.; May, A.M. The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A New Theory of Suicide Rooted in the “Ideation-to-Action” Framework. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 2015, 8, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C. The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis 2011, 32, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total TT | Trimester 2 | Trimester 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | <40 Years Old | 40–69 Years Old | >70 Years Old | <40 Years Old | 40–69 Years Old | >70 Years Old | <40 Years Old | 40–69 Years Old | >70 Years Old | |

| Men | 2015–2019 | 14.0 | 39.2 | 21.0 | 3.4 | 10.2 | 7.0 | 4.2 | 10.8 | 5.2 |

| 2019 | 17 | 42 | 17 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 18 | 6 | |

| 2020 | 15 | 38 | 26 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 16 | |

| 2021 | 5 * | 42 | 18 | 1 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 12 | 3 | |

| Women | 2015–2019 | 2.8 | 10.6 * | 3.8 | 0,4 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 1.6 |

| 2019 | 2 | 10 * | 2 * | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| 2020 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| 2021 | 2 | 13 * | 2 * | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| Both | 2015–2019 | 16.8 | 50.0 | 24.6 | 3.8 | 13 | 7.8 | 5 | 13.8 | 6.8 |

| 2019 | 19 | 52 | 19 * | 5 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 20 | 6 | |

| 2020 | 18 | 41 | 34 * | 5 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 20 | |

| 2021 | 7 * | 55 | 20 * | 2 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 15 | 3 |

| Total TT | Trimester 2 | Trimester 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | <40 Years Old | 40–69 Years Old | >70 Years Old | <40 Years Old | 40–69 Years Old | >70 Years Old | <40 Years Old | 40–69 Years Old | >70 Years Old | |

| Men | 2015–2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 (1.12–8.07) * | |

| 2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.44 (0.19–1.02) | 2.64 (1.03–6.75) * | |

| 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 2021 | 2.96 (1.07–8.14) * | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5.32 (1.55–18.26) * | ||

| Women | 2015–2019 | - | 0.27 (0.08–0.97) * | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2019 | – | 0.3 (0.08–1.08) | 3.98 (1.33–11.91) * | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 2021 | - | 0.23 (0.07–0.82) * | 3.97 (1.33–11.87) * | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Both | 2015–2019 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.89 (1.21–6.91) * |

| 2019 | – | – | 1.77 (1.01––3.11) * | – | – | – | – | 0.4 (0.17–0.9) * | 3.31 (1.33–8.24) * | |

| 2020 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 2021 | 2.53 (1.06–6.07) * | - | 1.69 (0.97–2.94) | 2.96 (1.07–8.14) * | - | - | - | - | 6.63 (1.97–22.31) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puig-Amores, I.; Martín-Mora-Parra, G.; Cuadrado-Gordillo, I.; Morales-Sanhueza, J. Older People at Risk of Suicide: A Local Study During the COVID-19 Confinement Period. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141735

Puig-Amores I, Martín-Mora-Parra G, Cuadrado-Gordillo I, Morales-Sanhueza J. Older People at Risk of Suicide: A Local Study During the COVID-19 Confinement Period. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141735

Chicago/Turabian StylePuig-Amores, Ismael, Guadalupe Martín-Mora-Parra, Isabel Cuadrado-Gordillo, and Jessica Morales-Sanhueza. 2025. "Older People at Risk of Suicide: A Local Study During the COVID-19 Confinement Period" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141735

APA StylePuig-Amores, I., Martín-Mora-Parra, G., Cuadrado-Gordillo, I., & Morales-Sanhueza, J. (2025). Older People at Risk of Suicide: A Local Study During the COVID-19 Confinement Period. Healthcare, 13(14), 1735. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141735