Health Professionals’ Views on Euthanasia: Impact of Traits, Religiosity, Death Perceptions, and Empathy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Euthanasia

1.1.2. End of Life

1.1.3. Empathy

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Participants’ Socio-Demographic Profile

2.3.2. Euthanasia Attitude Scale

2.3.3. Death Attitude Profile Scale

2.3.4. Scale of Empathy

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

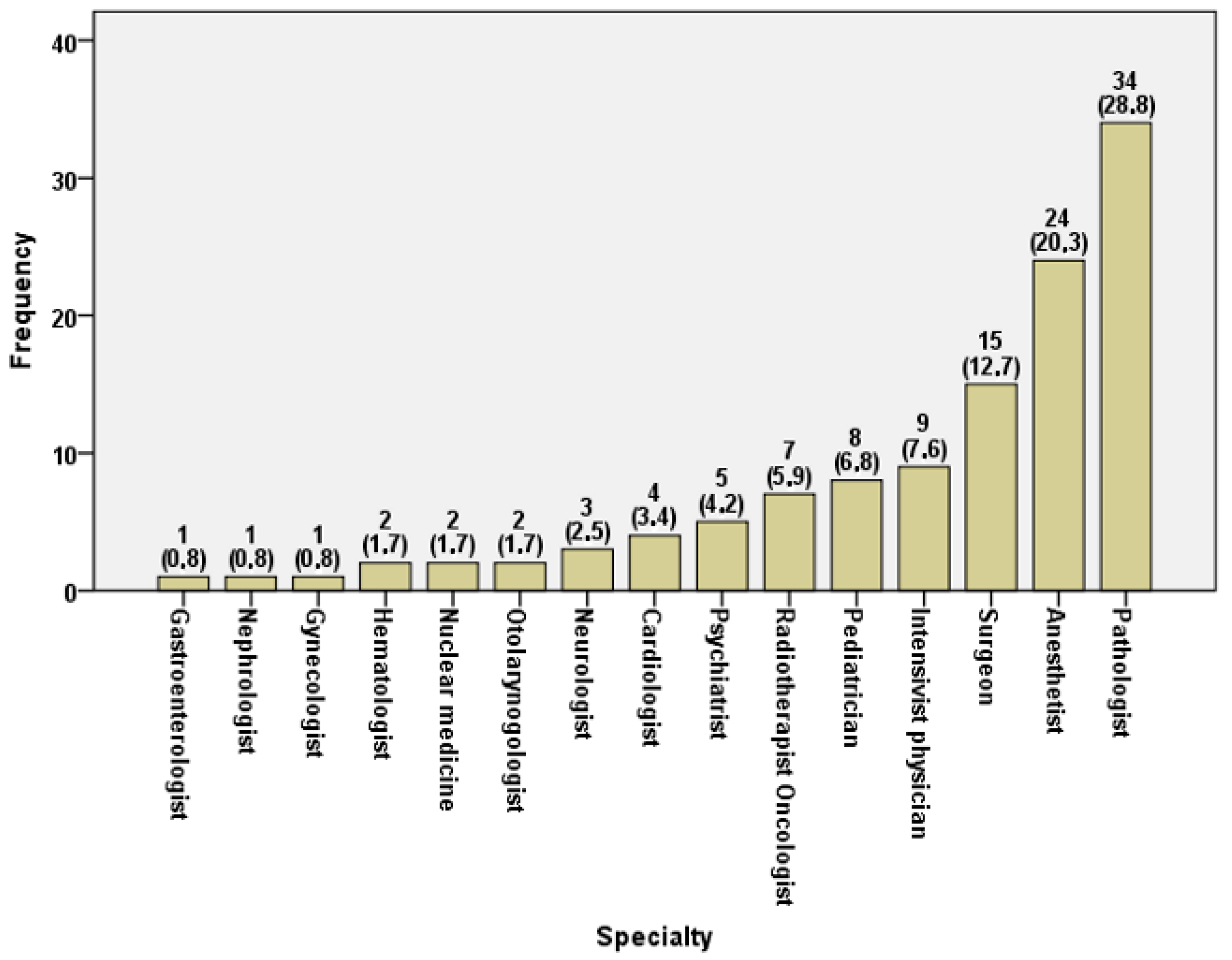

3.1. Participants’ Profile

3.2. ATE Scale Analysis

3.3. Multiple Regression Models for ATE Prediction

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations of This Study

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernández-Martínez, E.; Fernández-Muñoz, J.J.; Romero-Blanco, C.; Parra-Fernández, M.L.; Onieva-Zafra, M.D. Spanish version of the attitude towards euthanasia scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Marcoux, I.; Bilsen, J.; Deboosere, P.; Van Der Wal, G.; Deliens, L. European public acceptance of euthanasia: Socio-demographic and cultural factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia in 33 European countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, Z.A.; Overholser, J.C.; Danielson, C.K. Predictors of attitudes towards Physician-Assisted Suicide. Omega 2003, 47, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, D.W.; Marcus, B.S.; Wakim, P.G.; Mercurio, M.R.; Kopf, G.S. Health Care Professionals’ Attitudes About Physician-Assisted Death: An analysis of their justifications and the roles of terminology and patient competency. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 54, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroforou, N.; Michalodimitrakis, N. Euthanasia in Greece, Hippocrates’ birthplace. Eur. J. Health Law. 2001, 8, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Olalla, F. La eutanasia: Un derecho del siglo xxi. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 381–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Castro, M.P.R.; Antunes, G.C.; Marcon, L.M.P.; Andrade, L.S.; Rückl, S.; Andrade, V.L.Â. Eutanásia e suicídio assistido em países ocidentais: Revisão sistemática. Rev. Bioét 2016, 24, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, H. Euthanasia; Academic: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nnadi-Okolo, E.E. Euthanasia and the healthcare professional. Hosp. Pharm. 1995, 30, 208–210, 213, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, D.; Gupta, A. Euthanasia—Review and update through the lens of a psychiatrist. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2023, 32, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Voultsos, P.; Njau, S.N.; Vlachou, M. The issue of euthanasia in Greece from a legal viewpoint. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2010, 17, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabriseilabi, S.; Williams, J. Dimensions of religion and attitudes toward euthanasia. Death Stud. 2020, 46, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, R.D.; Wilson, D.M.; Malpas, P. Assisted or hastened death: The healthcare practitioner’s dilemma. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2012, 4, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Death Anxiety Handbook: Research, Instrumentation, and Application, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincher, M.; Florian, V. The complex and multifaceted nature of the fear of personal death: The multidimensional model of Victor Florian. In Death Attitudes: Existential & Spiritual Issues; Tomer, A., Wong, P.T.P., Grafton, E., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying; Collier Books/Macmillan Publishing Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Klug, L.; Sinha, A. Death Acceptance: A two-Component formulation and scale. Omega J. Death Dying 1988, 18, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, S.R.; Flannelly, K.J.; Weaver, A.J.; Costa, K.G. The influence of religion on death anxiety and death acceptance. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2004, 8, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turillazzi, E.; Maiese, A.; Frati, P.; Scopetti, M.; Di Paolo, M. Physician–Patient relationship, assisted suicide and the Italian Constitutional Court. J. Bioethical Inq. 2021, 18, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo, M.; Gori, F.; Papi, L.; Turillazzi, E. A review and analysis of new Italian law 219/2017: ‘provisions for informed consent and advance directives treatment’. BMC Med. Ethics 2019, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picón-Jaimes, Y.A.; Lozada-Martinez, I.D.; Orozco-Chinome, J.E.; Montaña-Gómez, L.M.; Bolaño-Romero, M.P.; Moscote-Salazar, L.R.; Janjua, T.; Rahman, S. Euthanasia and assisted suicide: An in-depth review of relevant historical aspects. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 75, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.H. The structure of empathy in social work practice. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2011, 21, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudatsou, M.; Stavropoulou, A.; Philalithis, A.; Koukouli, S. The role of empathy in health and social care professionals. Healthcare 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R. The Social Work Dictionary, 4th ed.; NASW Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, S.; Sethuramalingam, V. Empathy in psychosocial intervention: A theoretical overview. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 20, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C.R. Empathic: An unappreciated way of being. Consult. Psychol. 1975, 5, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudatsou, M.; Stavropoulou, A.; Alegakis, A.; Philalithis, A.; Koukouli, S. Self-Reported Assessment of Empathy and its Variations in a sample of Greek social workers. Healthcare 2021, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M. Ten Approaches for Enhancing Empathy in Health and Human Services Cultures. J. Health Hum. Serv. Adm. 2009, 31, 412–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; Mangione, S.; Nasca, T.J.; Cohen, M.J.M.; Gonnella, J.S.; Erdmann, J.B.; Veloski, J.; Magee, M. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: Development and Preliminary Psychometric data. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2001, 61, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Vergare, M.J.; Maxwell, K.; Brainard, G.; Herrine, S.K.; Isenberg, G.A.; Veloski, J.; Gonnella, J.S. The Devil is in the Third Year: A Longitudinal Study of Erosion of Empathy in Medical School. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonvicini, K.A.; Perlin, M.J.; Bylund, C.L.; Carroll, G.; Rouse, R.A.; Goldstein, M.G. Impact of communication training on physician expression of empathy in patient encounters. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 75, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Porat, A.; Itzhaky, H. Burnout among trauma social workers: The contribution of personal and environmental resources. J. Soc. Work. 2014, 15, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagaman, M.A.; Geiger, J.M.; Shockley, C.; Segal, E.A. The Role of Empathy in Burnout, Compassion Satisfaction, and Secondary Traumatic Stress among Social Workers. Soc. Work. 2015, 60, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeno, E.J.; Ting, L.; Wade, K. Predicting empathy in helping professionals: Comparison of social work and nursing students. Soc. Work. Educ. 2017, 37, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryn, M.; Hardeman, R.R.; Phelan, S.M.; Burke, S.E.; Przedworski, J.; Allen, M.L.; Burgess, D.J.; Ridgeway, J.; White, R.O.; Dovidio, J.F. Psychosocial predictors of attitudes toward physician empathy in clinical encounters among 4732 1st year medical students: A report from the CHANGES study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 96, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.; Buvaneswari, G.M.; Meenakshi, A. Predictors of empathy in women social workers. J. Soc. Work. 2018, 20, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S.; Bhuvaneswari, G.M. Reflective ability, empathy, and emotional intelligence in undergraduate social work students: A cross-sectional study from India. Soc. Work. Educ. 2016, 35, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Waqas, A.; Fatima, N.; Lodhi, H.W.; Sharif, M.W.; Ilahi, M. Association of attitudes towards euthanasia with religiosity, emotional empathy and exposure to the terminally ill. J. Pak. Psychiatr. Soc. 2015, 12, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tol, D.G.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Van Der Heide, A. Empathy and the application of the ‘unbearable suffering’ criterion in Dutch euthanasia practice. Health Policy 2012, 105, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, J.; Clair, J.M.; Ritchey, F.J. A Scale to Assess Attitudes toward Euthanasia. Omega J. Death Dying 2005, 51, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, J.A.; Aghababaei, N.; Nannini, D. Culture, personality, and attitudes toward euthanasia. Omega J. Death Dying 2015, 72, 247–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P.; Reker, G.T.; Gesser, G. Death Attitude Profile—Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death (DAP-R). In Death Anxiety Handbook: Research, Instrumentation, and Application; Neimeyer, R.A., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 121–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gesser, G.; Wong, P.T.P.; Reker, G.T. Death attitudes across the life-span: The development and validation of the Death Attitude Profile (DAP). Omega 1988, 18, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojat, M.; Gonnella, J.S.; Nasca, T.J.; Mangione, S.; Vergare, M.; Magee, M. Physician Empathy: Definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, T.R.V.; Casero, A.M.C.; González, Y.R.; Albaladejo, J.A.B.; Hanlon, L.F.M.; Llamas, M.I.G. Opinions of nurses regarding Euthanasia and Medically Assisted Suicide. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 1721–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijmakers, N.J.H.; Van Der Heide, A.; Kouwenhoven, P.S.C.; Van Thiel, G.J.M.W.; Van Delden, J.J.M.; Rietjens, J.C. Assistance in dying for older people without a serious medical condition who have a wish to die: A national cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Ethics 2013, 41, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, E. The goals of Medicine and Compassion in the ethical Assessment of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide: Relieving pain and suffering by protecting, promoting, and maintaining the person’s Well-Being. J. Palliat. Care 2022, 37, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiannis, P.; Fanouraki-Stavrakaki, E.; Manthou, P.; Intas, G. Investigation on the attitudes and perspectives of medical and nursing staff about euthanasia: Data from four regional Greek hospitals. Cureus 2024, 16, e53990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, H.D.; Hayslip, B.; Murdock, M.E.; Maloy, R.; Servaty, H.L.; Henard, K.; Lopez, L.; Lysaght, R.; Moreno, G.; Moroney, T.; et al. Measuring Attitudes toward Euthanasia. Omega J. Death Dying 1995, 30, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudatsou, M.; Stavropoulou, A.; Rovithis, M.; Koukouli, S. Views and challenges of COVID-19 vaccination in the primary health care sector. A Qualitative study. Vaccines 2023, 11, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, M.F.; Kho, M.; Thomas, E.F.; Decety, J.; Molenberghs, P.; Amiot, C.E.; Lizzio-Wilson, M.; Wibisono, S.; Allan, F.; Louis, W. The moderating role of different forms of empathy on the association between performing animal euthanasia and career sustainability. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 53, 1088–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedivitis, R.A.; de Matos, L.L.; de Castro, M.A.F.; de Castro, A.A.F.; Giaxa, R.R.; Tempski, P.Z. Medical students’ and residents’ views on euthanasia. BMC Med. Ethics 2023, 24, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, A.I.; Robbins, P.; Friedman, J.P.; Meyers, C.D. More than a feeling: Counterintuitive effects of compassion on moral judgment. In Advances in Experimental Philosophy of Mind; Sytsma, J., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2014; pp. 125–179. [Google Scholar]

- Moudatsou, M.; Kritsotakis, G.; Koutis, A.; Alegakis, A.; Panagoulopoulou, E.; Philalithis, A. Comparison of self-reported adherence to cervical and breast cancer screening guidelines in relation to the researcher’s profession. HJNS 2019, 12, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 117 | 25.2 |

| Female | 348 | 74.8 | |

| Age (mean ± SD) (min–max) | 42.6 ± 10.9 | 20–79 | |

| Age groups | ≤30 | 74 | 15.9 |

| 31–40 | 139 | 29.9 | |

| 41–50 | 140 | 30.1 | |

| 51+ | 112 | 24.1 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 185 | 39.8 |

| Married | 241 | 51.8 | |

| Divorced | 32 | 6.9 | |

| Widowed | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Educational level | Secondary Education | 27 | 5.8 |

| University | 236 | 50.8 | |

| Master’s/PhD | 202 | 43.4 | |

| Profession | Social workers | 185 | 39.8 |

| Physicians | 122 | 26.2 | |

| Nurses | 79 | 17.0 | |

| Physiotherapists | 31 | 6.7 | |

| Other health professionals | 21 | 4.5 | |

| Psychologists | 20 | 4.3 | |

| Professional experience | 0–5 | 108 | 23.2 |

| (years) | 6–10 | 76 | 16.3 |

| 11–15 | 71 | 15.3 | |

| 16–20 | 71 | 15.3 | |

| 21–30 | 92 | 19.8 | |

| >31 | 47 | 10.1 | |

| Employment status | Permanent | 303 | 65.1 |

| Not permanent | 162 | 34.9 | |

| Working hours | Full time | 451 | 97.0 |

| Part time | 14 | 3.0 | |

| Sector | Public | 313 | 67.3 |

| Private | 152 | 32.7 | |

| Workplace | Hospital | 266 | 57.2 |

| Other | 199 | 42.8 | |

| Working with end-stage | Yes | 256 | 55.1 |

| Patients | No | 209 | 44.9 |

| Target group | Adults | 222 | 47.7 |

| Elders | 44 | 9.5 | |

| Minors | 34 | 7.3 | |

| >1 target group | 165 | 35.5 |

| ATE Scale | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | |||

| Gender | Male | 117 | 25.0 | 9.1 | 0.168 1 |

| Female | 348 | 23.8 | 9.2 | ||

| Age | ≤30 | 74 | 22.3 | 7.2 | 0.293 2 |

| 31–40 | 139 | 24.2 | 8.4 | ||

| 41–50 | 140 | 24.0 | 9.6 | ||

| 51+ | 112 | 25.3 | 10.4 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 185 | 23.5 | 8.3 | 0.213 2 |

| Married | 241 | 24.1 | 9.4 | ||

| Divorced/Widowed | 39 | 26.7 | 11.2 | ||

| Educational level | Secondary Education | 27 | 22.9 | 8.3 | 0.889 2 |

| University | 236 | 24.1 | 9.0 | ||

| Master’s/PhD | 202 | 24.2 | 9.5 | ||

| ATE Total | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | |||

| Professional group * | Health professionals | 201 | 25.0 | 9.8 | 0.155 2 |

| Psychosocial/Mental health professionals | 205 | 23.5 | 9.0 | ||

| Other | 59 | 22.9 | 6.9 | ||

| health professionals | 201 | 25.0 | 9.8 | 0.155 2 | |

| Professional experience | 0–5 | 108 | 22.3 | 8.2 | 0.360 2 |

| 6–10 | 76 | 24.2 | 8.6 | ||

| 11–15 | 71 | 24.4 | 9.4 | ||

| 16–20 | 71 | 24.4 | 8.3 | ||

| 21–30 | 92 | 25.4 | 10.8 | ||

| >31 | 47 | 24.6 | 9.4 | ||

| Employment status | Permanent | 303 | 24.3 | 9.3 | 0.594 1 |

| Not permanent | 162 | 23.7 | 8.8 | ||

| Working hours | Full time | 451 | 24.1 | 9.2 | 0.989 1 |

| Part time | 14 | 24.0 | 9.1 | ||

| Sector | Public | 313 | 24.6 | 9.3 | 0.110 1 |

| Private | 152 | 23.1 | 8.7 | ||

| Health service category and specialization | Non-specialized/General medical unit | 411 | 24.3 | 9.2 | 0.263 2 |

| Palliative care | 34 | 21.8 | 9.9 | ||

| Loss and bereavement management | 14 | 25.1 | 7.6 | ||

| Other | 6 | 21.8 | 8.0 | ||

| Working with end-stage patients | Yes | 256 | 23.6 | 9.5 | 0.251 1 |

| No | 209 | 24.7 | 8.7 | ||

| Target group | Adults | 222 | 25.1 | 9.6 | 0.045 2 |

| Elders | 44 | 20.7 | 8.6 | ||

| Minors | 34 | 24.5 | 8.8 | ||

| >1 target group | 165 | 23.6 | 8.5 | ||

| ATE | JSE | FoD | DaV | Nac | Aac | Eac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | −0.008 | 0.010 | −0.358 | 0.099 | 0.092 | −0.173 |

| P | 0.856 | 0.829 | 0.000 | 0.032 | 0.048 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mimarakis, D.; Moudatsou, M.; Kolokotroni, P.; Alegakis, A.; Koukouli, S. Health Professionals’ Views on Euthanasia: Impact of Traits, Religiosity, Death Perceptions, and Empathy. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141731

Mimarakis D, Moudatsou M, Kolokotroni P, Alegakis A, Koukouli S. Health Professionals’ Views on Euthanasia: Impact of Traits, Religiosity, Death Perceptions, and Empathy. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141731

Chicago/Turabian StyleMimarakis, Dimitrios, Maria Moudatsou, Philippa Kolokotroni, Athanasios Alegakis, and Sofia Koukouli. 2025. "Health Professionals’ Views on Euthanasia: Impact of Traits, Religiosity, Death Perceptions, and Empathy" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141731

APA StyleMimarakis, D., Moudatsou, M., Kolokotroni, P., Alegakis, A., & Koukouli, S. (2025). Health Professionals’ Views on Euthanasia: Impact of Traits, Religiosity, Death Perceptions, and Empathy. Healthcare, 13(14), 1731. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141731