Enhancing Pediatric Outpatient Medical Services Through the Implementation of the Smart Well Child Center Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

- (1)

- Planning phase: The planning phase spanned approximately four months and involved a structured, multi-stakeholder collaboration process. In-depth discussions were conducted with pediatricians, nurses, hospital administrators, and IT personnel to evaluate the existing WCC service workflow. These consultations aimed to: (1) assess operational feasibility for digital integration; (2) map current service processes and identify gaps; (3) analyze pain points affecting caregiver satisfaction and service time; (4) gather functional and technical requirements for the proposed application; and (5) align clinical goals with system design priorities. This phase also included informal caregiver interviews to understand user expectations and digital literacy challenges. Outputs from these discussions were translated into a set of system specifications, which were used to design low-fidelity wireframes and flow diagrams for stakeholder feedback. Parallel to this, the IT team conducted an infrastructure readiness assessment to evaluate compatibility with existing hospital systems.

- (2)

- Analysis phase: A comprehensive analysis of the current workflow and the proposed new workflow was conducted, with particular emphasis on identified problems and user needs. This phase also involved the establishment of a MySQL database management system, enabling data exchange between the WCC application database and the HosXP system in the hospital information system (HIS) via an API.

- (3)

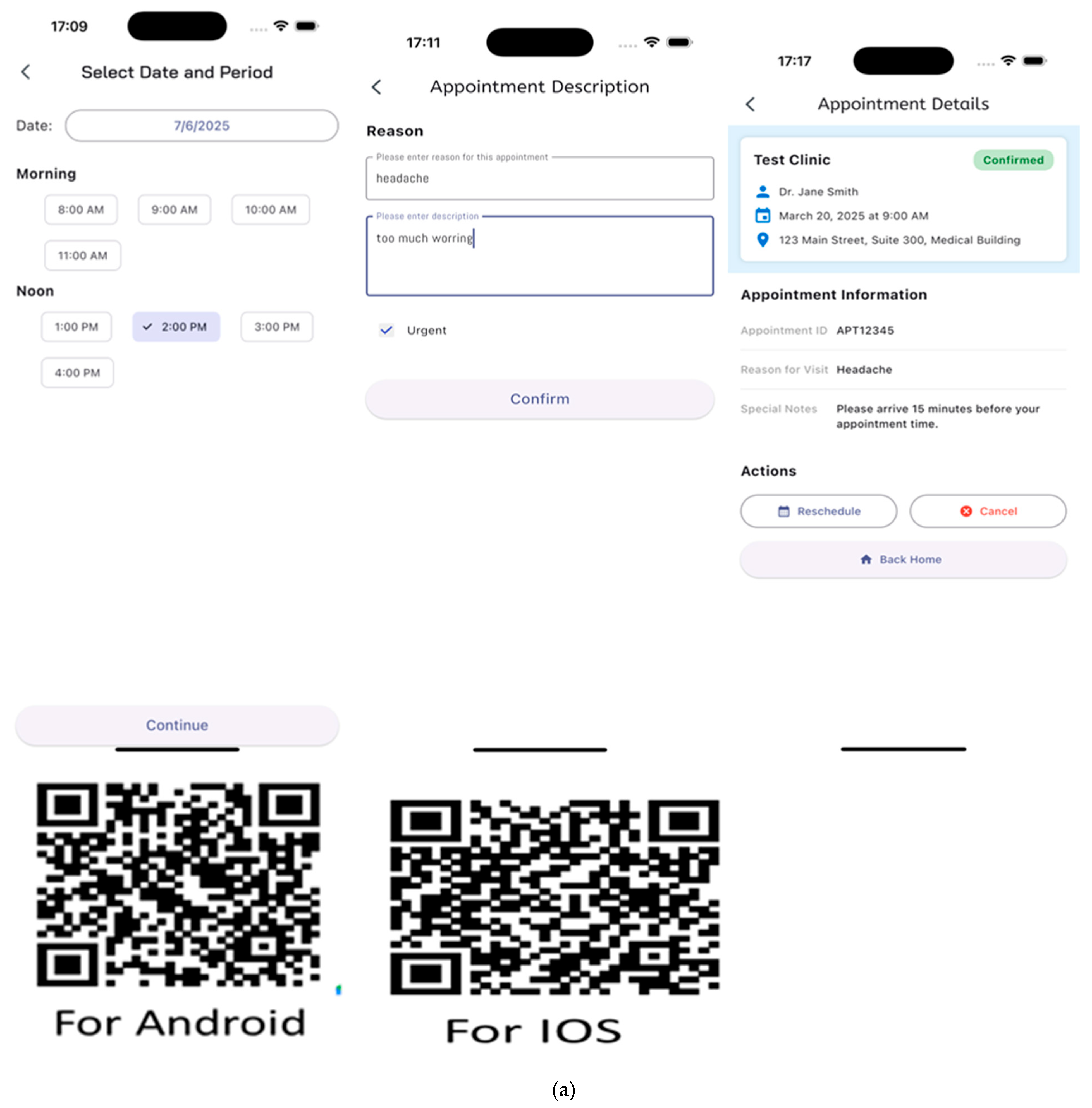

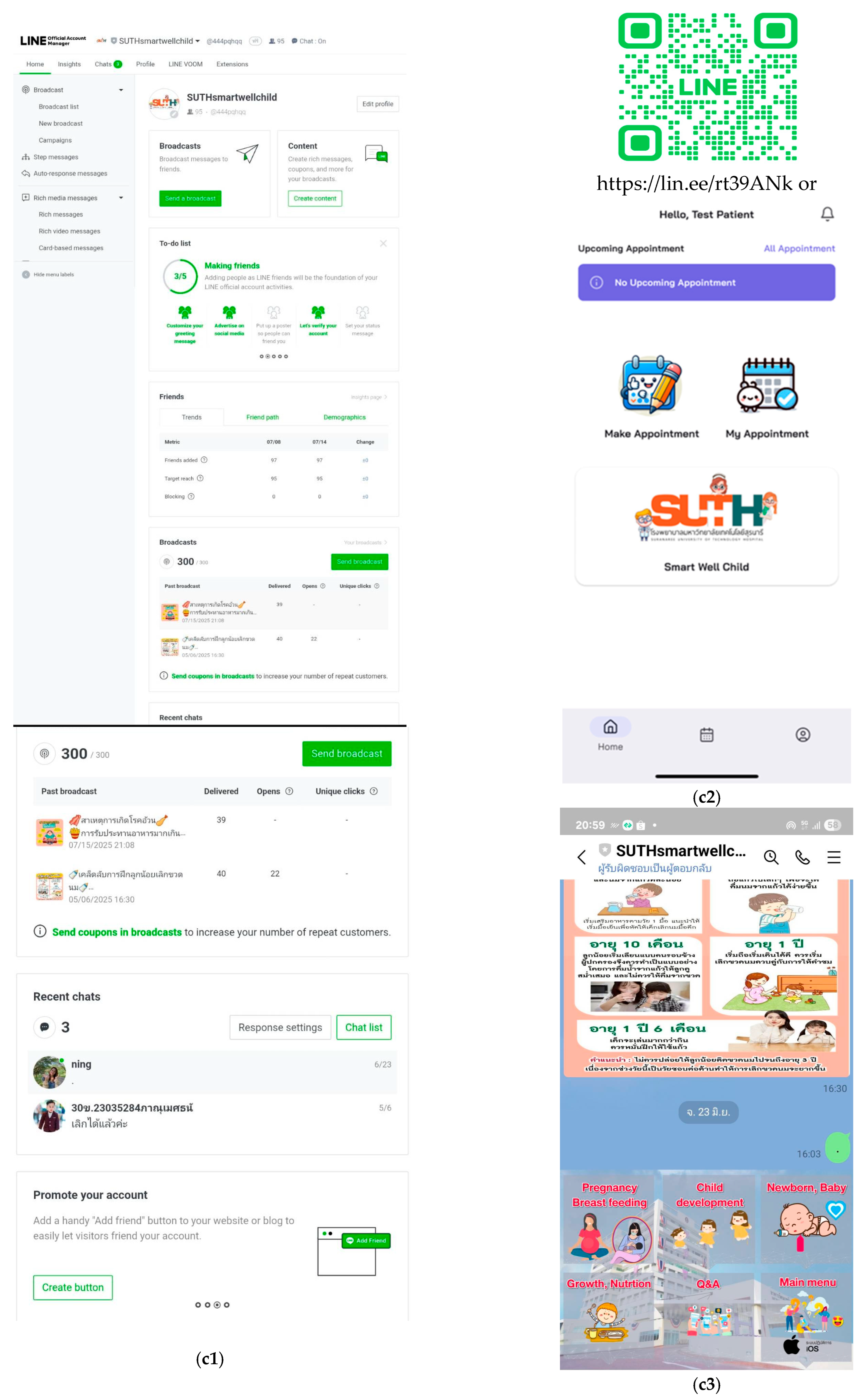

- Design phase: The physical service area was developed alongside the application. User interfaces and data visualizations were designed for various user groups, including administrators, physicians, nurses, and child caregivers.

- (4)

- Implementation phase: The application was deployed in the production environment and underwent extensive user testing over the course of one month. During this period, user feedback was systematically collected to identify and resolve issues. The application’s performance was evaluated by both IT professionals and end-users.

2.2. Participants

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Development of the Smart Well Child Center Application and Integration into Clinical Service Infrastructure

3.2. Pilot Evaluation of the Smart Well Child Center: System Performance and Caregiver Satisfaction

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hagan, J.F.; Shaw, J.; Duncan, P. Bright Futures; American Academy of Pediatrics: Itasca, IL, USA, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Howland, K.; Edvardsson, K.; Lees, H.; Hooker, L. Telehealth use in the well-child health setting. A systematic review of acceptability and effectiveness for families and practitioners. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 8, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerdpiromluk, S.; Youdyoung, S.; Duangdech, W. Quality Improvement of the Well-Child Clinic Care Model on Parental Health Literacy and Child Health Outcomes. Nurs. J. CMU 2024, 51, 204–222. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.J.; Ma, J.; Zuckerman, B.; Car, J. The Opportunities for Telehealth in Pediatric Practice and Public Health. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 67, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coker, T.R.; DuPlessis, H.M.; Davoudpour, R.; Moreno, C.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Chung, P.J. Well-Child Care Practice Redesign for Low-Income Children: The Perspectives of Health Plans, Medical Groups, and State Agencies. Acad. Pediatr. 2012, 12, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.; ’t Hart, P. Inaction and public policy: Understanding why policymakers ‘do nothing’. Policy Sci. 2019, 52, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, T.; Marinucci, J.; Tranby, E.P.; Frantsve-Hawley, J. The Effect of Well Child Visit Location on Preventative Dental Visit. Children 2021, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foldager Jeppesen, S.; Vilhjálmsson, R.; Åvik Persson, H.; Kristensson Hallström, I. Parental satisfaction with paediatric care with and without the support of an eHealth device: A quasi-experimental study in Sweden. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gund, A.; Sjöqvist, B.A.; Wigert, H.; Hentz, E.; Lindecrantz, K.; Bry, K. A randomized controlled study about the use of eHealth in the home health care of premature infants. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindkvist, R.M.; Sjöström-Strand, A.; Landgren, K.; Johnsson, B.A.; Stenström, P.; Hallström, I.K. “In a Way We Took the Hospital Home”-A Descriptive Mixed-Methods Study of Parents’ Usage and Experiences of eHealth for Self-Management after Hospital Discharge Due to Pediatric Surgery or Preterm Birth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, M.J.; Kakavand, K.; Careaga, D.; Gozalians, S. Shifting from in-person to virtual home visiting in Los Angeles County: Impact on programmatic outcomes. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, D.; Venegas, M.; Coker, T.R.; Guerrero, A.D. Promoting Child Development During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Parental Perceptions of Tele-Home Visits in Early Head Start Programs. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 26, 2496–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboobeh, N.; Atefeh, S.; Asghar, E.; Hamed, Z. Development of a Post Discharge Telecare Program for Premature Infants in COVID-19 Era: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.S.; Chien, W.T. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of an Online Educational Program for Primiparous Women to Improve Breastfeeding. J. Hum. Lact. 2023, 39, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muto, H.; Yamamoto, R.; Ishii, K.; Kakubari, R.; Takaoka, S.; Mabuchi, A.; Mitsuda, N. Risk assessment of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy with maternal characteristics in early gestation: A single-center cohort study. Taiwan J. Obs. Gynecol. 2016, 55, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, K.; Moreno, C.; Chung, P.J.; Elijah, J.; Coker, T.R. Well-child care clinical practice redesign at a community health center: Provider and staff perspectives. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2014, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiberson, M.; Rodríguez, B.L.; Zajacova, A. Accuracy of Telehealth-Administered Measures to Screen Language in Spanish-Speaking Preschoolers. Telemed. J. e-Health 2015, 21, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahma, R.A.; Ishaq, M.; Affriyenni, Y. The development of application for child care services in facilitating distance learning. In Development, Social Change and Environmental Sustainability; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, K.E.; Kendall, J.E. Systems Analysis and Design, 10th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kirakowski, J.; Corbett, M.; Sumi, M. The software usability measurement inventory. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 1993, 24, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala, A.; Chen, F. Appointment scheduling problem in complexity systems of the healthcare services: A comprehensive review. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5819813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, W.M.G.R.S.; de Onis, M. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr. 2006, 95, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J.; Chunsuwan, I.; Bunnag, P.; Gronholm, P.C.; Estrin, G.L. Thailand’s national universal developmental screening programme for young children: Action research for improved follow-up. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.A.; Booth, A.T.; Schnabel, A.; Wright, B.J.; Painter, F.L.; McIntosh, J.E. Exploring the Efficacy of Telehealth for Family Therapy Through Systematic, Meta-analytic, and Qualitative Evidence. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 244–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gresh, A.; Wilson, D.; Fenick, A.; Patil, C.L.; Coker, T.; Rising, S.S.; Glass, N.; Platt, R. A conceptual framework for group well-child care: A tool to guide implementation, evaluation, and research. Matern. Child Health J. 2023, 27, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, K.; Jansen, E.; Cromack, C.; Gallegos, D. Can a call make a difference? Measured change in women’s breastfeeding self-efficacy across call interactions on a telephone helpline. Matern. Child Health J. 2018, 22, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seguranyes, G.; Costa, D.; Fuentelsaz-Gallego, C.; Beneit, J.V.; Carabantes, D.; Gómez-Moreno, C.; Palacio-Tauste, A.; Pauli, A.; Abella, M.; Group, P.T.R. Efficacy of a videoconferencing intervention compared with standard postnatal care at primary care health centres in Catalonia. Midwifery 2014, 30, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Fung, R.Y. Approximate dynamic programming approaches for appointment scheduling with patient preferences. Artif. Intell. Med. 2018, 85, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.A.; Duan, N.; Regalado, M.; Klein, D.J. Anticipatory guidance: What information do parents receive? What information do they want? Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents; American Academy of Pediatrics: Itasca, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C.; Gund, A.; Sjöqvist, B.A.; Bry, K. Using telemedicine in the care of newborn infants after discharge from a neonatal intensive care unit reduced the need of hospital visits. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raatz, M.; Ward, E.C.; Marshall, J.; Burns, C.L. Developing the system architecture for conducting synchronous paediatric feeding assessments via telepractice. J. Telemed. Telecare 2019, 25, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: Key Findings of the 2020 Edition. UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mo-suwan, L. Prevalence of childhood and adolescent obesity in Thailand: A review. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. Chotmaihet Thangphaet 2014, 97, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

| Personal Information | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child Caregivers | |||

| Gender | Male | 15 | 17.6 |

| Female | 70 | 82.4 | |

| Age | Under 20 years | 1 | 1.2 |

| 20–30 years | 32 | 37.6 | |

| 31–40 years | 40 | 47.1 | |

| 41–50 years | 10 | 11.8 | |

| 51–60 years | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Over 60 years | - | - | |

| Occupation | Government official | 17 | 20.0 |

| State enterprise employee | 3 | 3.5 | |

| Employee/staff of a company/store | 24 | 28.2 | |

| Business owner/trader | 15 | 17.6 | |

| Freelancer/daily wage worker | 8 | 9.4 | |

| Others | 18 | 21.2 | |

| Relationship | Father | 14 | 16.5 |

| Mother | 66 | 77.6 | |

| Uncle or Aunt | 1 | 1.2 | |

| Grandfather or Grandmother | 4 | 4.7 | |

| Hometown | Nakhon Ratchasima | 78 | 91.8 |

| Others | 7 | 8.2 | |

| Number of Visits | First time | 4 | 4.7 |

| 2 times | 21 | 24.7 | |

| 3 times or over | 60 | 70.6 | |

| Child | |||

| Gender | Male | 54 | 63.5 |

| Female | 31 | 36.5 | |

| Percentage of weight | Obese | 20 | 23.5 |

| for age (%: W/A) | Overweight | 3 | 3.5 |

| Normal weight | 53 | 62.4 | |

| Slightly underweight | 3 | 3.5 | |

| Underweight | 6 | 7.1 | |

| Mean ± SD: 125.65 ± 64.27 | |||

| Percent by height | Tall | 18 | 21.2 |

| for age (%: H/A) | Moderately tall | 2 | 2.4 |

| Normal | 54 | 63.5 | |

| Slightly short | 3 | 3.5 | |

| Short | 8 | 9.4 | |

| Mean ± SD: 106.8 ± 21.16 | |||

| Percent weight | Severely obese | 5 | 6.0 |

| for height (%: W/H) | Obese | 6 | 7.1 |

| Overweight | 2 | 2.4 | |

| Well-proportioned | 63 | 75.0 | |

| Thinness | 4 | 4.8 | |

| Severe thinness | 4 | 4.8 | |

| Mean ± SD: 101.97 ± 20.45 | |||

| Bottle feeding | Not used | 25 | 29.4 |

| Used | 60 | 70.6 | |

| Gross motor skills | Age-appropriate | 59 | 98.3 |

| Suspected delay | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Delayed | - | - | |

| Fine motor skills | Age-appropriate | 59 | 98.3 |

| Suspected delay | - | - | |

| Delayed | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Emotional and social | Age-appropriate | 57 | 95.5 |

| Suspected delay | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Delayed | - | - | |

| Language | Age-appropriate | 57 | 95.5 |

| Suspected delay | - | - | |

| Delayed | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Dental check-up | Normal | 60 | 100.0 |

| Tooth decay | - | - | |

| Oral care | Fluoride coating | 57 | 95.0 |

| Referred to dentistry | 3 | 5.0 | |

| Performance Domain | Mean ± SD | Levels |

|---|---|---|

| Function requirement test | 4.27 ± 0.24 | Highest |

| Function test | 4.11 ± 0.31 | High |

| Usability test | 4.00 ± 0.42 | High |

| Security test | 3.92 ± 0.27 | High |

| Overall performance | 4.06 ± 0.77 | High |

| Satisfaction with Healthcare Services | Times | Mean ± SD | Levels | Repeated Measures ANOVA or Paired t-Test | Times | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After Use | After Use 1 Month | ||||||

| Ease of access to services | Before | 3.29 ± 0.56 | Moderate | F = 313.274 ** | 0.502 | |||

| After use | 4.58 ± 0.48 | Highest | −1.297 ** | |||||

| After use 1 mo. | 4.60 ± 0.40 | Highest | −1.315 ** | 0.018 | ||||

| Quality of medical care | Before | 3.27 ± 0.42 | Moderate | F = 326.162 ** | 0.717 | |||

| After use | 4.57 ± 0.51 | Highest | −1.300 ** | |||||

| After use 1 mo. | 4.66 ± 0.52 | Highest | −1.388 ** | 0.088 | ||||

| Service timeliness | Before | 3.26 ± 0.69 | Moderate | F = 128.708 ** | 0.555 | |||

| After use | 4.55 ± 0.58 | Highest | −1.294 ** | |||||

| After use 1 mo. | 4.54 ± 0.71 | Highest | −1.282 ** | −0.012 | ||||

| Medical equipment and general environment | Before | 3.58 ± 0.50 | High | F = 123.906 ** | 0.505 | |||

| After use | 4.52 ± 0.56 | Highest | −0.953 ** | |||||

| After use 1 mo. | 4.58 ± 0.58 | Highest | −1.012 ** | 0.059 | ||||

| Smart Well Child Care service and application | Before | - | - | t = 0.206 | 0.023 | |||

| After use | 4.54 ± 0.55 | Highest | ||||||

| After use 1 mo. | 4.56 ± 0.59 | Highest | −0.017 | |||||

| Overall satisfaction | Before | 3.35 ± 0.41 | Moderate | F = 439.797 ** | 0.606 | |||

| After use | 4.58 ± 0.57 | Highest | −1.235 ** | |||||

| After use 1 mo. | 4.59 ± 0.33 | Highest | −1.249 ** | 0.014 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uengarporn, N.; Saengthongpitag, T.; Chongjaroenjai, P.; Pongpitakdamrong, A.; Sriratthnarak, W.; Rianteerasak, P.; Mongkolkul, K.; Srinuchasart, P.; Srichaisawat, P.; Mungklang, N.; et al. Enhancing Pediatric Outpatient Medical Services Through the Implementation of the Smart Well Child Center Application. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141676

Uengarporn N, Saengthongpitag T, Chongjaroenjai P, Pongpitakdamrong A, Sriratthnarak W, Rianteerasak P, Mongkolkul K, Srinuchasart P, Srichaisawat P, Mungklang N, et al. Enhancing Pediatric Outpatient Medical Services Through the Implementation of the Smart Well Child Center Application. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141676

Chicago/Turabian StyleUengarporn, Naporn, Teerapat Saengthongpitag, Poonyanuch Chongjaroenjai, Atcha Pongpitakdamrong, Wutthipong Sriratthnarak, Phonpimon Rianteerasak, Kanyarat Mongkolkul, Paninun Srinuchasart, Panuwat Srichaisawat, Nicharee Mungklang, and et al. 2025. "Enhancing Pediatric Outpatient Medical Services Through the Implementation of the Smart Well Child Center Application" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141676

APA StyleUengarporn, N., Saengthongpitag, T., Chongjaroenjai, P., Pongpitakdamrong, A., Sriratthnarak, W., Rianteerasak, P., Mongkolkul, K., Srinuchasart, P., Srichaisawat, P., Mungklang, N., Sanguantrakul, R., Tongdee, P., Kiatmongkol, W., Sihaklang, B., Putrakul, P., Namvichaisirikul, N., & Saritshasombat, P. (2025). Enhancing Pediatric Outpatient Medical Services Through the Implementation of the Smart Well Child Center Application. Healthcare, 13(14), 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141676