Listening Until the End: Best Practices and Guidelines for Auditory Care in Palliative Sedation in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Foundation and Evolution of Palliative Sedation Guidelines

3.2. Key Guidelines and Recommendations

3.3. Comparative Analysis of European Guidelines

3.4. Global Guidelines and Recent Updates

3.5. Consensus and Gaps

3.6. Comprehensive Care Recommendations for Palliative Sedation

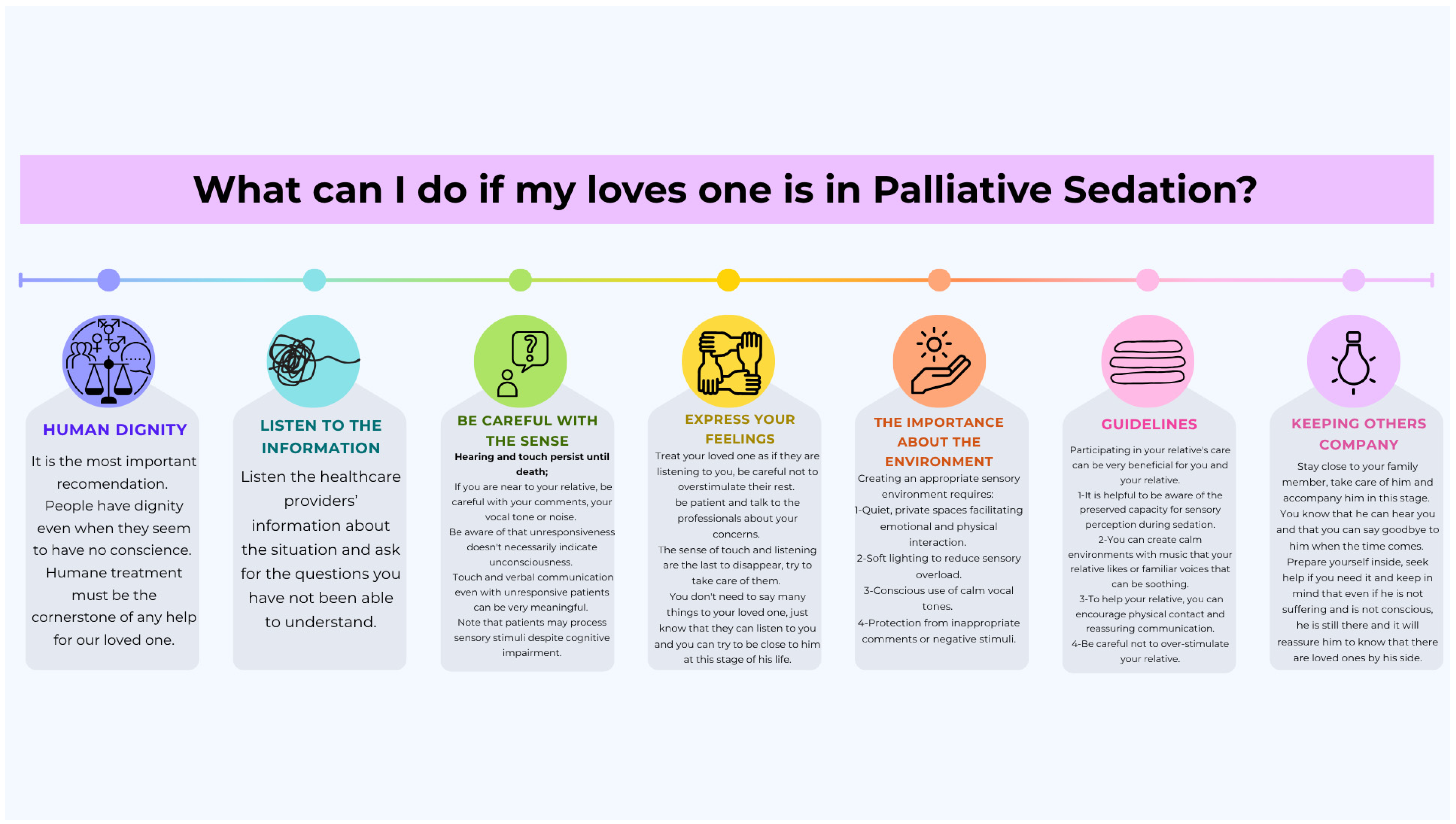

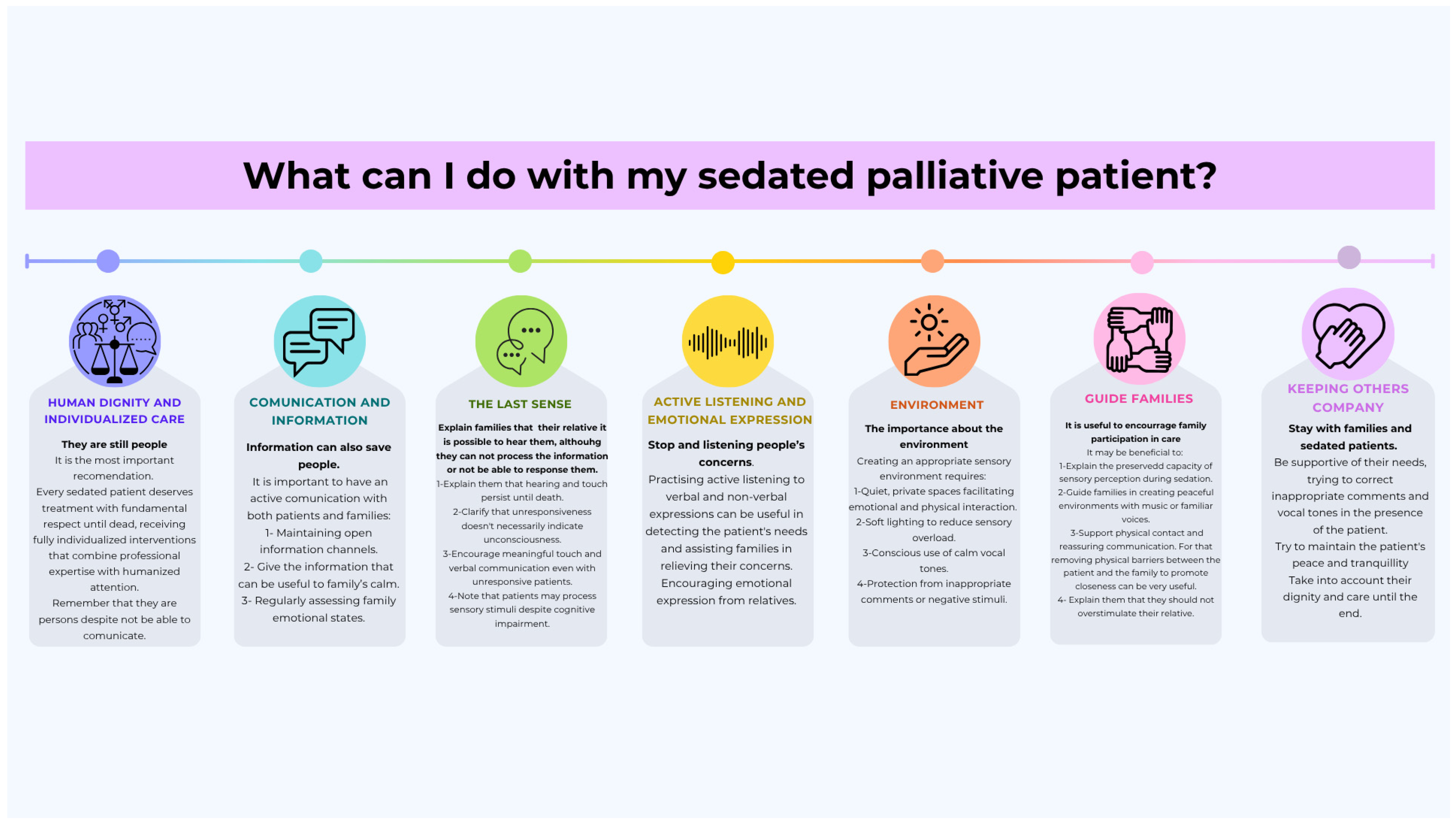

- Human dignity and individualized careEvery sedated patient deserves treatment with fundamental respect until dead, receiving fully individualized interventions that combine professional expertise with humanized attention [19,20,21,33]. Healthcare teams should provide comprehensive care focused on alleviating suffering while preserving patient dignity throughout the sedation process [19,20,21,33].

- Communication and family supportActive communication with both patients and families forms the cornerstone of quality care. This includes (i) maintaining open information channels [34,35]; (ii) practicing active listening for both verbal and nonverbal expressions of needs [33]; (iii) regularly assessing family emotional states [20,21,38]; and (iv) encouraging emotional expression from relatives [20,39].

- Sensory environment optimizationCreating an appropriate sensory environment requires (i) quiet, private spaces facilitating emotional and physical interaction [19,21,33,35,40]; (ii) soft lighting to reduce sensory overload [33,35]; (iii) conscious use of calm vocal tones [33,35]; and (iv) protection from inappropriate comments or negative stimuli [33].

- Sensory preservation strategiesClinical teams should (i) explain to families that hearing and touch persist until death [2,19]; (ii) clarify that unresponsiveness does not necessarily indicate unconsciousness [17]; (iii) encourage meaningful touch and verbal communication even with unresponsive patients [2,35,41]; and (iv) note that patients may process sensory stimuli despite cognitive impairment [34].

- Family engagement guidelinesHealthcare providers should (i) actively encourage family participation in care [19,35]; (ii) explain the preserved capacity for sensory perception during sedation [17,41]; (iii) guide families in creating peaceful environments with music or familiar voices [17,19,41]; and (iv) support physical contact and reassuring communication [2,39].

4. Discussion

4.1. Heterogeneity in European Guidelines and the Leadership of EAPC

4.2. Hearing as an Underestimated Dimension in Palliative Sedation

4.3. Practical Implications and Proposed Improvements

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Palliative Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Bugarín, R.; Fernández, J.A.; Triñanes, Y. Guía de Práctica Clínica Sobre Atención Paliativa al Adulto en Situación de Últimos Días; Agencia de Conocimiento en Salud (ACIS); Unidad de Asesoramiento Científico-técnico, Avalia-t: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beeley, L.J.; Winfield, S.; Adams, D. Making the Most of a Palliative Care Experience. BMJ 2020, 368, l6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A.; Singh, D.; Chanchlani, R.; Pando, A. A Review on Palliative Care Challenges and Benefits. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2022, 16, OE1–OE6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S.; Intravaia, G.; Villari, P.; Ferrera, P.; David, F.; Casuccio, A. Controlled Sedation for Refractory Symptoms in Dying Patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2009, 37, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arantzamendi, M.; Belar, A.; Payne, S.; Rijpstra, M.; Preston, N.; Menten, J.; Van der Elst, M.; Radbruch, L.; Hasselaar, J.; Centeno, C. Clinical Aspects of Palliative Sedation in Prospective Studies. A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 61, 831–844.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundon, E.G.; Gallagher, R.E.; Ward, L.M. Electrophysiological Evidence of Preserved Hearing at the End of Life. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pedrajas, F.; Arroyo, J.L. Midazolam in anesthesiology. Rev. Med. Univ. Navar. 1989, 33, 211–221. [Google Scholar]

- Kamali, A.; Milosavljevic, S.; Gandhi, A.; Lano, K.R.; Shobeiri, P.; Sherbaf, F.G.; Sair, H.I.; Riascos, R.F.; Hasan, K.M. The Cortico-Limbo-Thalamo-Cortical Circuits: An Update to the Original Papez Circuit of the Human Limbic System. Brain Topogr. 2023, 36, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamietto, M.; de Gelder, B. Neural Bases of the Non-Conscious Perception of Emotional Signals. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 697–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A.R. Sentir lo Que Sucede; Andrés Bello: Bío Bío, Chile, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gökçek, E.; Kaydu, A. The Effects of Music Therapy in Patients Undergoing Septorhinoplasty Surgery under General Anesthesia. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020, 86, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, V.X.; Sleurink, K.J.; Janssen, J.C.; Wijnhoven, B.P.L.; Jeekel, J.; Klimek, M. Perception of Auditory Stimuli during General Anesthesia and Its Effects on Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Anaesth. 2021, 68, 1231–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahloul, M.; Mhamdi, S.; Nakhli, M.S.; Sfeyhi, A.N.; Azzaza, M.; Chaouch, A.; Naija, W. Effects of Music Therapy under General Anesthesia in Patients Undergoing Abdominal Surgery. Libyan J. Med. 2017, 12, 1260886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hole, J.; Hirsch, M.; Ball, E.; Meads, C. Music as an Aid for Postoperative Recovery in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2015, 386, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Sleigh, J. Consciousness and General Anesthesia: Challenges for Measuring the Depth of Anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2024, 140, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascanio León, B.; Benítez-Rosario, M.A.; González Bolaños, I.; González García, M.; Guerrero Cedeño, V.; Miranda Cáceres, R.; Morales Pérez, S.; Otero Tejera, M.; Wallis Gómez, V.G. Sedación Paliativa: Conceptos, Bioética y Aspectos Técnicos; Servicio Canario de la Salud: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Surges, S.M.; Garralda, E.; Jaspers, B.; Brunsch, H.; Rijpstra, M.; Hasselaar, J.; Van der Elst, M.; Menten, J.; Csikós, Á.; Mercadante, S.; et al. Review of European Guidelines on Palliative Sedation: A Foundation for the Updating of the European Association for Palliative Care Framework. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, N.I.; Radbruch, L. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Recommended Framework for the Use of Sedation in Palliative Care. Palliat. Med. 2009, 23, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garralda, E.; Busa, C.; Pozsgai, É.; Osztromok-Lukacs, V.; Csikós, A.; Radbruch, L.; Hasselaar, J.; Menten, J.; Payne, S.; Adile, C.; et al. Regulations on Palliative Sedation: An International Survey across Eight European Countries. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surges, S.M.; Brunsch, H.; Jaspers, B.; Apostolidis, K.; Cardone, A.; Centeno, C.; Cherny, N.; Csikós, À.; Fainsinger, R.; Garralda, E.; et al. Revised European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework on palliative sedation: An international Delphi study. Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miccinesi, G.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Deliens, L.; Paci, E.; Bosshard, G.; Nilstun, T.; Norup, M.; van der Wal, G. Continuous Deep Sedation: Physicians’ Experiences in Six European Countries. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2006, 31, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, C. Continuous Deep Sedation in Medical Practice: A Descriptive Study. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2010, 39, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, B.; Nauck, F.; Lindena, G.; Elsner, F.; Ostgathe, C.; Radbruch, L. Palliative Sedation in Germany: How Much Do We Know? A Prospective Survey. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anquinet, L.; Rietjens, J.A.C.; Seale, C.; Seymour, J.; Deliens, L.; van der Heide, A. The Practice of Continuous Deep Sedation Until Death in Flanders (Belgium), The Netherlands, and the U.K.: A Comparative Study. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2012, 44, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietjens, J.A.; Voorhees, J.R.; van der Heide, A.; Drickamer, M.A. Approaches to Suffering at the End of Life: The Use of Sedation in the USA and Netherlands. J. Med. Ethics 2014, 40, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seale, C.; Raus, K.; Bruinsma, S.; van der Heide, A.; Sterckx, S.; Mortier, F.; Payne, S.; Mathers, N.; Rietjens, J.; Addington-Hall, J.; et al. The Language of Sedation in End-of-Life Care: The Ethical Reasoning of Care Providers in Three Countries. Health: An. Interdiscip. J. Soc. Social Study Health Illn. Med. 2015, 19, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, J.; Rietjens, J.; Bruinsma, S.; Deliens, L.; Sterckx, S.; Mortier, F.; Brown, J.; Mathers, N.; van der Heide, A.; Addington-Hall, J.; et al. Using Continuous Sedation until Death for Cancer Patients: A Qualitative Interview Study of Physicians’ and Nurses’ Practice in Three European Countries. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, S.; Blondeau, D.; Turcotte, V.; Borasio, G.D.; Currat, T.; Foley, R.-A.; Beauverd, M. The Use of Palliative Sedation: A Comparison of Attitudes of French-Speaking Physicians from Quebec and Switzerland. Palliat. Support. Care 2015, 13, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.A.; Hasselaar, J. European Palliative Sedation Project. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Imai, K.; Mori, M.; Yokomichi, N.; Tsuneto, S. Defining “Continuous Deep Sedation” Using Treatment Protocol: A Proposal Article. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2022, 3, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights EU Charter of Fundamental Rights-Title I Dignity. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/eu-charter/title/title-i-dignity (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Comité de Ética Asistencial de Xerencia Xestion Integrada a Coruña Protocolo de Sedacion Paliativa. 2012. Available online: https://xxicoruna.sergas.gal/Paxinas/web.aspx?idTax=12500&idLista=3&idContido=483&migtab=458%3B482%3B483&tipo=paxtab&idioma=es#:~:text=Protocolo%20sedaci%C3%B3n%20paliativa%20del%20%C3%81rea%20Sanitaria%20de%20A%20Coru%C3%B1a%20y%20Cee (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Porta i Sales, J.; Bernades i Teixidó, A.; López Romboly, M.; Frances, L. Palliative Sedation Practical Guide. 2012. Available online: https://docs.academia.cat/i5906150 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Gomez-Batiste, X.; Gonzalez-Olmedo, M.; Gonzalez-Barboteo, J.; Duran, A.; Codorniu, N.; Trelis, J.; Tuca, A.; Porta, J. Principios Básicos de Atención Paliativa de Personas Con Enfermedades Crónicas Evolutivas y Pronostico de Vida Limitado y Sus Familias. 2011. Available online: https://ico.gencat.cat/web/.content/minisite/ico/professionals/documents/qualy/arxius/doc_principios_basicos_de_la_atencion_paliativa_vf.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Koper, I.; Hasselaar, J.; Payne, C. The Role of Palliative Sedation in Palliative Care; Palliative Sedation; European Association for Palliative Care: Vilvoorde, Belgium, 2024; ISBN 9789090377414. [Google Scholar]

- Gurschick, L.; Mayer, D.K.; Hanson, L.C. Palliative Sedation. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2015, 32, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, M.G.; Trota, R.A.; Cantera, J.B.; Blanco, M.C.; Casasnovas, L.C.; del Castillo, Á.G.; Vargas, R.M.; Gil, J.R.; Sendín, J.J.R. Guía de Sedación Paliativa Secpal; Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Médicos (CGCOM): Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Ruiz, M.; Ayuso Carmona, A.; Blanco Guerrero, M.; Blanco Toro, L.; Cuervo Pinna, M.; Díaz Díez, F.; Durán Martinez, A.; Encinas Martínez, P.; García Caballero, M.; Gil Sierra, M.; et al. Manual de Cuidados Paliativos de Extremadura. 2019. Available online: https://saludextremadura.ses.es/filescms/paliex/uploaded_files/CustomContentResources/MANUAL%20CUIDADOS%20PALIATIVOS%202020%20-%20version%20digital.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Equipo de Soporte en Atención Domiciliaria; Pérez de Miguel, J.; Utor Ponce, L.; Gaton Martinez, L. Guía de Sedación Paliativa. 2013. Available online: https://ingesa.sanidad.gob.es/dam/jcr:fb7c58fd-1692-4e91-a307-7d5f9b30c74c/Guia_sedacion_paliativa.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Almaraz Ruiz de Eguilaz, M.; Ochoa Bedoya, I.; Anaut Mayo, P.; Martín Ortega, P.; Delgado Vicente, M.; González Izquierdo, A. Guía de Sedación Paliativa En El País Vasco; Osakidetza: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Morales, M.; Mendoza-Popoca, C.Ú. Conciencia de La Consciencia Durante La Anestesia. Rev. Mex. Anestesiol. 2022, 45, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Castellanos, I.; Ortega González-Gallego, M.I.; Bermejo-Cantarero, A.; Expósito-González, R.; Rodríguez-Almagro, J.; Martínez-Rodríguez, S.; Redondo-Tébar, A. Listening Until the End: Best Practices and Guidelines for Auditory Care in Palliative Sedation in Europe. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141664

Rodríguez-Castellanos I, Ortega González-Gallego MI, Bermejo-Cantarero A, Expósito-González R, Rodríguez-Almagro J, Martínez-Rodríguez S, Redondo-Tébar A. Listening Until the End: Best Practices and Guidelines for Auditory Care in Palliative Sedation in Europe. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141664

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Castellanos, Ismael, María Isabel Ortega González-Gallego, Alberto Bermejo-Cantarero, Raúl Expósito-González, Julián Rodríguez-Almagro, Sandra Martínez-Rodríguez, and Andrés Redondo-Tébar. 2025. "Listening Until the End: Best Practices and Guidelines for Auditory Care in Palliative Sedation in Europe" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141664

APA StyleRodríguez-Castellanos, I., Ortega González-Gallego, M. I., Bermejo-Cantarero, A., Expósito-González, R., Rodríguez-Almagro, J., Martínez-Rodríguez, S., & Redondo-Tébar, A. (2025). Listening Until the End: Best Practices and Guidelines for Auditory Care in Palliative Sedation in Europe. Healthcare, 13(14), 1664. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141664