General Practitioners’ Perceptions on Prescribing Coastal Visits for Mental Health in Flanders (Belgium)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.2. Recruitment and Sample

2.3. Data Analysis

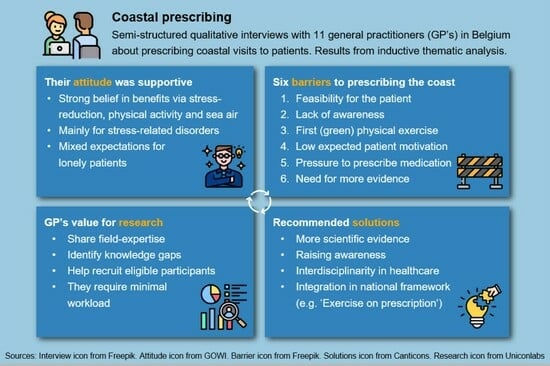

3. Results

3.1. Attitudes Towards Coastal Prescriptions

3.1.1. GPs’ (Coastal) Prescribing Behavior

3.1.2. Opinions About Effects of the Coast on Health

3.1.3. Relevant Patient Profiles

3.2. Barriers for Implementing Coastal Prescriptions

3.2.1. Feasibility for the Patient

3.2.2. Lack of Awareness

3.2.3. Priority for (Green) Exercise

3.2.4. Personal Preference and Patient Motivation

3.2.5. Pressure to Prescribe Medication

3.2.6. Need for More Evidence

3.3. Potential Opportunities

3.3.1. Developing a Broader Framework

3.3.2. Interdisciplinary Awareness

3.3.3. Group Activities/Buddy System

3.4. Involvement of GPs in Research

4. Discussion

4.1. Moving Towards Coastal Prescribing

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GP | General practitioner |

| SES | Socio-economic status |

References

- WHO. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Risks to Mental Health: An Overview of Vulnerabilities and Risk Factors—Background Paper by WHO Secretariat for the Development of a Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoncker, J.; Vanderhasselt, M.A.; Ottaviani, C.; Slavich, G.M. Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic and beyond: The Importance of the Vagus Nerve for Biopsychosocial Resilience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 125, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triliva, S.; Ntani, S.; Giovazolias, T.; Kafetsios, K.; Axelsson, M.; Bockting, C.; Buysse, A.; Desmet, M.; Dewaele, A.; Hannon, D.; et al. Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives on Mental Health Service Provision: A Pilot Focus Group Study in Six European Countries. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robberegt, S.J.; Brouwer, M.E.; Kooiman, B.E.A.M.; Stikkelbroek, Y.A.J.; Nauta, M.H.; Bockting, C.L.H. Meta-Analysis: Relapse Prevention Strategies for Depression and Anxiety in Remitted Adolescents and Young Adults. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 62, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grellier, J.; White, M.P.; Albin, M.; Bell, S.; Elliott, L.R.; Gascón, M.; Gualdi, S.; Mancini, L.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Sarigiannis, D.A.; et al. BlueHealth: A Study Programme Protocol for Mapping and Quantifying the Potential Benefits to Public Health and Well-Being from Europe’s Blue Spaces. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H2020 SOPHIE Consortium. A Strategic Research Agenda for Oceans and Human Health in Europe; H2020 SOPHIE Project: Ostend, Belgium, 2020; ISBN 9789492043894. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; Berry, P.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.R.; Geneletti, D.; Calfapietra, C. A Framework for Assessing and Implementing the Co-Benefits of Nature-Based Solutions in Urban Areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullam, J.; Hunt, H.; Lovell, R.; Husk, K.; Byng, R.; Richards, D.; Bloomfield, D.; Warber, S.; Tarrant, M.; Lloyd, J.; et al. A Handbook for Nature on Prescription to Promote Mental Health; European Centre for Environment and Human Health: Cornwall, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.-Y.; Astell-Burt, T.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Feng, X. Effect of Nature Prescriptions on Cardiometabolic and Mental Health, and Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Lancet Planet. Health 2023, 7, e313–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juster-Horsfield, H.H.; Bell, S.L. Supporting ‘Blue Care’ through Outdoor Water-Based Activities: Practitioner Perspectives. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2021, 14, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, E.; Kindermann, G.; Domegan, C.; Carlin, C. Blue Care: A Systematic Review of Blue Space Interventions for Health and Wellbeing. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Green Social Prescribing. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/social-prescribing/green-social-prescribing/ (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Maund, P.R.; Irvine, K.N.; Reeves, J.; Strong, E.; Cromie, R.; Dallimer, M.; Davies, Z.G. Wetlands for Wellbeing: Piloting a Nature-Based Health Intervention for the Management of Anxiety and Depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooyberg, A.; Michels, N.; Roose, H.; Everaert, G.; Mokas, I.; Malina, R.; Vanderhasselt, M.A.; De Henauw, S. The Psychophysiological Reactivity to Beaches vs. to Green and Urban Environments: Insights from a Virtual Reality Experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 91, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero-Mas, M.; Gidlow, C.J.; Martínez, D.; De Bont, J.; Carrasco-Turigas, G.; Martínez-Íñiguez, T.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; Seto, E.; et al. The Effect of Randomised Exposure to Different Types of Natural Outdoor Environments Compared to Exposure to an Urban Environment on People with Indications of Psychological Distress in Catalonia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vert, C.; Gascon, M.; Ranzani, O.; Márquez, S.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Carrasco-Turigas, G.; Arjona, L.; Koch, S.; Llopis, M.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; et al. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Repeated Short Walks in a Blue Space Environment: A Randomised Crossover Study. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, J.K.; White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Grellier, J.; Bell, S.; Bratman, G.N.; Economou, T.; Gascon, M.; Lõhmus, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; et al. Applying an Ecosystem Services Framework on Nature and Mental Health to Recreational Blue Space Visits across 18 Countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaenssens, G.; De Raedemaecker, H.; Fremout, J.; Verbruggen, R. “Natuurcontact Op Verwijzing” in de Huisartsenpraktijk, Met Focus Op Vier Chronische Aandoeningen. Master’s Thesis, Universiteit Antwerpen, Antwerpen, Belgium, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lysens de Oliveira e Silva-Van Acker, J. Kwaliteitsverbeterend Project: Huisartsen Motiveren Voor “Bewegen Op Verwijzing”. Master’s Thesis, Universiteit Antwerpen, Antwerpen, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Walter, L.G.; Arroll, B.; Tilyard, M.W.; Russell, D.G. Green Prescriptions: Attitudes and Perceptions of General Practitioners towards Prescribing Exercise. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1997, 47, 567–569. [Google Scholar]

- Mailey, E.L.; Besenyi, G.M.; Durtschi, J. Mental Health Practitioners Represent a Promising Pathway to Promote Park-Based Physical Activity. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2022, 22, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smyter, L. “Bewegen Op Verwijzing”: Een Evaluatie Door de Huisarts. Master’s Thesis, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.C. Conducting Semi-Structured Interviews. In Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, M.G. Creating Qualitative Interview Protocols. Int. J. Sociotechnol. Knowl. Dev. 2012, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The Qualitative Research Interview. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical Guidance to Qualitative Research. Part 1: Introduction. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 23, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample Sizes for Saturation in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review of Empirical Tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Qualitative Research in Psychology Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooyberg, A.; Roose, H.; Grellier, J.; Elliott, L.R.; Lonneville, B.; White, M.P.; Michels, N.; De Henauw, S.; Vandegehuchte, M.; Everaert, G. General Health and Residential Proximity to the Coast in Belgium: Results from a Cross-Sectional Health Survey. Environ. Res. 2020, 184, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, F.M.; Ettema, D.F.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Pierik, F.H.; Dijst, M.J. How Do Type and Size of Natural Environments Relate to Physical Activity Behavior? Health Place 2017, 46, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, S.; Mauro, M.; Grigoletto, A.; Toselli, S.; Maietta Latessa, P. The Effect of Physical Activity Interventions Carried Out in Outdoor Natural Blue and Green Spaces on Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murrin, E.; Taylor, N.; Peralta, L.; Dudley, D.; Cotton, W.; White, R.L. Does Physical Activity Mediate the Associations between Blue Space and Mental Health? A Cross-Sectional Study in Australia. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H.; Hartig, T. Alone or with a Friend: A Social Context for Psychological Restoration and Environmental Preferences. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staats, H.; Jahncke, H.; Herzog, T.R.; Hartig, T. Urban Options for Psychological Restoration: Common Strategies in Everyday Situations. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northrop, E.; Schuhmann, P.; Burke, L.; Fyall, A.; Alvarez, S.; Spenceley, A.; Becken, S.; Kato, K.; Roy, J.; Some, S.; et al. Opportunities for Transforming Coastal and Marine Tourism: Towards Sustainability, Regeneration and Resilience; High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Soshkin, M.; Calderwood, L.U. Travel & Tourism Development Index 2021: Rebuilding for a Sustainable and Resilient Future; World Economic Forum: Cologne, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Gascon, M.; Roberts, B.; Fleming, L.E. Blue Space, Health and Well-Being: A Narrative Overview and Synthesis of Potential Benefits. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, S.; Hagoort, K.; Scheepers, F.; Helbich, M. Does Residential Green and Blue Space Promote Recovery in Psychotic Disorders? A Cross-Sectional Study in the Province of Utrecht, the Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbich, M.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; White, M.; Hagedoorn, P. Living near Coasts Is Associated with Higher Suicide Rates among Females but Not Males: A Register-Based Linkage Study in the Netherlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, S.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Natural Environments—Healthy Environments? An Exploratory Analysis of the Relationship between Greenspace and Health. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B.W.; White, M.P.; Stahl-Timmins, W.; Depledge, M.H. Does Living by the Coast Improve Health and Wellbeing. Health Place 2012, 18, 1198–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, A.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; McAnirlin, O.; Yoon, H. Green Space and Health Equity: A Systematic Review on the Potential of Green Space to Reduce Health Disparities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, S.J.; Rodwell, L.D.; Shellock, R.J.; Williams, M.; Attrill, M.J.; Bedford, J.; Curry, K.; Fletcher, S.; Gall, S.C.; Lowther, J.; et al. Marine Parks for Coastal Cities: A Concept for Enhanced Community Well-Being, Prosperity and Sustainable City Living. Mar. Policy 2019, 103, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.J.; White, M.P.; Davison, S.M.C.; Zhang, L.; McMeel, O.; Kellett, P.; Fleming, L.E. Coastal Proximity and Visits Are Associated with Better Health but May Not Buffer Health Inequalities. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Health for Everyone?: Social Inequalities in Health and Health Systems; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, J.; Calnan, M.; Prior, L.; Lewis, G.; Kessler, D.; Sharp, D. A Qualitative Study Exploring How GPs Decide to Prescribe Antidepressants. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2005, 55, 755–762. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.F.; Williams, B.; Macgillivray, S.A.; Dougall, N.J.; Maxwell, M. “Doing the Right Thing”: Factors Influencing GP Prescribing of Antidepressants and Prescribed Doses. BMC Fam. Pract. 2017, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoglund, I.; Segesten, K.; Björkelund, C. GPs’ Thoughts on Prescribing Medication and Evidence-Based Knowledge: The Benefit Aspect Is a Strong Motivator. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2007, 25, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, N.; Michiels-Corsten, M.; Viniol, A.; Schleef, T.; Junius-Walker, U.; Krause, O.; Donner-Banzhoff, N. Professional Roles of General Practitioners, Community Pharmacists and Specialist Providers in Collaborative Medication Deprescribing—A Qualitative Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.; Thomas, F.; Byng, R.; McCabe, R. Exploring How Patients Respond to GP Recommendations for Mental Health Treatment: An Analysis of Communication in Primary Care Consultations. BJGP Open 2019, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.; Kessler, D.; Wiles, N.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Turner, K. GPs’ Views of Prescribing Beta-Blockers for People with Anxiety Disorders: A Qualitative Study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 74, e735–e741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Okada, H.; Nakayama, T. Social Prescribing from the Patient’s Perspective: A Literature Review. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2022, 23, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, A.; Storry, V.; Sewed, C.; Hodgson, J.C. A Mixed Methods Investigation into GP Attitudes and Experiences of Using Social Prescribing in Their Practice. J. Public Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, H.; Almond, S.; Walley, T. Influences on GPs’ Decision to Prescribe New Drugs—The Importance of Who Says What. Fam. Pract. 2003, 20, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, J.; Benz, A.; Holmgren, A.; Kinter, D.; McGarry, J.; Rufino, G. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Horticultural Therapy on Persons with Mental Health Conditions. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2017, 33, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavell, M.A.; Leiferman, J.A.; Gascon, M.; Braddick, F.; Gonzalez, J.C.; Litt, J.S. Nature-Based Social Prescribing in Urban Settings to Improve Social Connectedness and Mental Well-Being: A Review. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genter, C.; Roberts, A.; Richardson, J.; Sheaff, M. The Contribution of Allotment Gardening to Health and Wellbeing: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 78, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, J.S.; Coll-Planas, L.; Sachs, A.L.; Ursula, R.; Jansson, A.; Vladimira, D.; Daher, C.; Beacom, A.; Bachinski, K.; Garcia Velez, G.; et al. Nature-Based Social Interventions for People Experiencing Loneliness: The Rationale and Overview of the RECETAS Project (under Revision). Cities Health 2024, 8, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fann, J.R.; Jones, A.L.; Dikmen, S.S.; Temkin, N.R.; Esselman, P.C.; Bombardier, C.H. Depression Treatment Preferences after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009, 24, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osma, J.; Suso-Ribera, C.; Peris-Baquero, Ó.; Gil-Lacruz, M.; Pérez-Ayerra, L.; Ferreres-Galan, V.; Torres-Alfosea, M.Á.; López-Escriche, M.; Domínguez, O. What Format of Treatment Do Patients with Emotional Disorders Prefer and Why? Implications for Public Mental Health Settings and Policies. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks, C.; Barton, J.; Orbell, S.; Andrews, L. Psychological Benefits of Outdoor Physical Activity in Natural versus Urban Environments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2022, 14, 1037–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahindru, A.; Patil, P.; Agrawal, V. Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e33475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, S.A.; Sutcliffe, J.T.; Fernandez, D.; Liddelow, C.; Aidman, E.; Teychenne, M.; Smith, J.J.; Swann, C.; Rosenbaum, S.; White, R.L.; et al. Context Matters: A Review of Reviews Examining the Effects of Contextual Factors in Physical Activity Interventions on Mental Health and Wellbeing. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2023, 25, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of Physical Activity Interventions for Improving Depression, Anxiety and Distress: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinde, S.; Bojke, L.; Coventry, P. The Cost Effectiveness of Ecotherapy as a Healthcare Intervention, Separating the Wood from the Trees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busk, H.; Sidenius, U.; Kongstad, L.P.; Corazon, S.S.; Petersen, C.B.; Poulsen, D.V.; Nyed, P.K.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Economic Evaluation of Nature-Based Therapy Interventions—A Scoping Review. Challenges 2022, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The Case for Investing in Public Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, A.; Basu, S.; Mckee, M.; Meissner, C.; Stuckler, D. Does Health Spending Stimulate Economic Growth? Glob. Health 2013, 9, 43. [Google Scholar]

- McDaid, D.; Park, A.-L. The Economic Case for Investing in Mental Health Prevention Summary; Mental Health Foundation: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Merkur, S.; Sassi, F.; McDaid, D. Promoting Health, Preventing Disease: Is There an Economic Case? WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013; 72p. [Google Scholar]

- White, M.P.; Yeo, N.; Vassiljev, P.; Lundstedt, R.; Wallergård, M.; Albin, M.; Lõhmus, M. A Prescription for “Nature”—The Potential of Using Virtual Nature in Therapeutics. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 3001–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, M.H.E.M.; Mimnaugh, K.J.; van Riper, C.J.; Laurent, H.K.; LaValle, S.M. Can Simulated Nature Support Mental Health? Comparing Short, Single-Doses of 360-Degree Nature Videos in Virtual Reality With the Outdoors. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogerson, M.; Wood, C.; Pretty, J.; Schoenmakers, P.; Bloomfield, D.; Barton, J. Regular Doses of Nature: The Efficacy of Green Exercise Interventions for Mental Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-Y.; Astell-Burt, T.; Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Feng, X. Green Space Quality and Health: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.Y.; Zhao, T.; Hu, L.X.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Heinrich, J.; Dharmage, S.C.; Jalaludin, B.; Knibbs, L.D.; Liu, X.X.; Luo, Y.N.; et al. Greenspace and Human Health: An Umbrella Review. Innovation 2021, 2, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, J.; Rogerson, M. The Importance of Greenspace for Mental Health. BJPsych. Int. 2017, 14, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooyberg, A.; Michels, N.; Allaert, J.; Vandegehuchte, M.B.; Everaert, G.; De Henauw, S.; Roose, H. ‘Blue’ Coasts: Unravelling the Perceived Restorativeness of Coastal Environments and the Influence of Their Components. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 228, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hooyberg, A.; De Wever Van der Heyden, L.; Severin, M.I.; De Henauw, S.; Everaert, G. General Practitioners’ Perceptions on Prescribing Coastal Visits for Mental Health in Flanders (Belgium). Healthcare 2025, 13, 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131599

Hooyberg A, De Wever Van der Heyden L, Severin MI, De Henauw S, Everaert G. General Practitioners’ Perceptions on Prescribing Coastal Visits for Mental Health in Flanders (Belgium). Healthcare. 2025; 13(13):1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131599

Chicago/Turabian StyleHooyberg, Alexander, Luka De Wever Van der Heyden, Marine I. Severin, Stefaan De Henauw, and Gert Everaert. 2025. "General Practitioners’ Perceptions on Prescribing Coastal Visits for Mental Health in Flanders (Belgium)" Healthcare 13, no. 13: 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131599

APA StyleHooyberg, A., De Wever Van der Heyden, L., Severin, M. I., De Henauw, S., & Everaert, G. (2025). General Practitioners’ Perceptions on Prescribing Coastal Visits for Mental Health in Flanders (Belgium). Healthcare, 13(13), 1599. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131599