1. Introduction

Globally, population aging is accelerating at an unprecedented pace. According to the World Population Prospects 2024 report, by the end of the 2070s, the number of people aged 65 and over is expected to surpass those under 18 [

1]. At present, China’s aging population has a large scale and a rapid development speed. By the end of 2024, the total number of people aged 60 and over in China had exceeded 300 million, reaching 22.0% of the total population, and the size of the population aged 65 and over had exceeded 220 million, accounting for 15.6% of the total population [

2].

As people age, they may face various physical, psychological, and social changes, such as functional decline, illness, increased loneliness, and social role changes [

3,

4]. The long-persisting negative stereotypes of older adults in society and the media, such as slow response and lack of energy, not only affect the attitudes of other groups towards older adults but also affect the subjective view of their aging [

5]. Self-perception of aging (SPA) refers to the subjective cognitive and emotional responses formed by older adults under the influence of physiological, psychological, and social aging challenges [

6]. The SPA is an important predictor of cognitive function [

7], mental health [

8], social relationships [

9], and longevity [

10].

The SPA is shaped by cultural context and prevailing social values [

11]. In collectivist cultures, strong family and community ties are highly valued, and older adults are often seen as bearers of tradition and sources of wisdom [

12]. In contrast, individualistic cultures tend to emphasize independence and productivity, which may inadvertently lead to the marginalization of older adults [

13]. Research has shown that individuals in collectivist societies generally hold more positive attitudes toward older adults [

14]. In the Chinese context, deeply rooted Confucian norms further influence the roles and expectations of older adults. Traditional values such as filial piety emphasize respect for and care for older adults, shaping their social status and perceptions of aging [

15,

16]. However, the rapid demographic aging is accompanied by increasing social pressures, and negative attitudes toward older adults have also begun to emerge within collectivist societies [

17]. Moreover, accelerated socio-economic development, urbanization, and shifts in family structures have led to changes in intergenerational relationships and the gradual weakening of traditional support systems [

18,

19]. Collectivist values and expectations may also influence the internalization of age-related stereotypes regarding the roles and contributions of older adults within the family and society [

20,

21]. Given these factors, a culturally sensitive assessment of SPA is crucial for understanding and addressing the needs and well-being of Chinese community-dwelling older adults.

The validity of studies on SPA is highly dependent on the quality of its assessment tools. There are several tools available to assess SPA, such as the Ageing Cognitions Scales (Age-Cog) [

22], the Aging Perception Questionnaire (APQ) [

6], and the Age-Related Changes Questionnaire (AARC) [

23]. However, researchers developed these instruments based on their research objectives or interpretations of SPA, and there are differences in measurement dimensions and theoretical basis. The research team previously systematically reviewed the psychometric properties of the existing assessment tools using the COSMIN method. The results showed that 10 of the 13 existing assessment tools were rated grade B, and three were rated grade C.

After discussion in the research group, it was found that the APQ has a high potential for application in the assessment of SPA. The original APQ, developed by Barker in 2007 based on the Common-Sense Model (CSM), comprises 49 items and eight dimensions: acute/chronic timeline, cyclical timeline, positive consequence, negative consequence, positive control, negative control, emotional representation, and identity [

6]. In addition, the items included in the “identity” dimension aimed to assess the extent to which older adults attributed their health problems to “getting older.” Barker suggested that the remaining seven dimensions, except for the “identity” dimension, could be integrated into a scale, and the reliability and validity of this scale have been verified in different cultural contexts.

The Chinese version of the APQ (C-APQ), translated and adapted by Chen et al. [

24], maintains the original multidimensional structure for use with Chinese older adults. Although its psychometric properties were validated in Shanghai community-dwelling older adults, C-APQ retains the length format of the original APQ, which may increase the response burden for older adults. Therefore, researchers in many countries have developed a short form of the APQ, effectively reducing the burden on participants while retaining the multidimensional structure of the original questionnaire.

Older adults from different cultures have some commonalities in their aging perception, but modernization processes, cultural differences, and social and family relationships may significantly affect their aging perception. In 2014, Sexton et al. developed the Brief APQ (B-APQ), a 17-item version based on data from the Irish Longitudinal Study of Ageing, which omitted the cyclical timeline dimension and combined negative control with negative consequences [

25]. The B-APQ was later translated into Chinese by Hu and has been used in related studies [

26]. However, combining dimensions in the B-APQ may introduce methodological bias and weaken the theoretical integrity. Recognizing this, Slotman et al. created the short version of the APQ (APQ-S), a 21-item form that retains all seven key dimensions of the original APQ, with demonstrated reliability and validity in the Dutch context [

27]. This version has not yet been translated and adapted among older adults in China. Additionally, Miremadi et al. translated the original APQ into Persian and revised the questionnaire based on Iranian older adults in 2020, resulting in the Persian version of the APQ (APQ-P) containing 20 items and four dimensions [

28].

In conclusion, the APQ, as an instrument developed based on the CSM, can comprehensively assess the multidimensional characteristics of older adults’ SPA. Although the theoretical structure of the original APQ is relatively complete, its large number of items may increase the fatigue of older adults when answering. While short forms like APQ-P and APQ-S offer improved convenience, they were developed using data from non-Chinese populations and have not been fully validated among Chinese community-dwelling older adults. Furthermore, the removal or combination of specific dimensions in existing short forms may compromise the theoretical comprehensiveness of SPA assessment.

Therefore, this study aimed to retain the core dimensions of the C-APQ and appropriately simplify items to reduce respondent burden, thereby developing the Chinese short-form APQ. The ultimate goal is to provide a scientific and reliable tool for assessing the SPA level of Chinese community-dwelling older adults and evaluating the effects of interventions. Healthcare professionals and community health workers can use the M-APQ for routine screening to identify older adults who may have negative perceptions of aging, allowing for early and targeted psychological or social interventions. Its brevity and ease of administration facilitate large-scale community-based health assessments and make it suitable for inclusion in annual health check-ups or home visits. In addition, the M-APQ can guide the design, implementation, and evaluation of evidence-based community health promotion programs to foster positive attitudes towards aging and ultimately improve health outcomes among older adults.

4. Discussion

According to the COSMIN guidelines, it is recommended to prioritize the selection and validation of existing instruments across diverse populations rather than developing new ones. Therefore, this study aims to optimize and revise the existing questionnaires. The optimization of instruments should begin with a clear conceptualization of the target construct to ensure comprehensive assessment [

52]. Based on qualitative research on the SPA of community-dwelling older adults, three new items were added to the emotional representation dimension. Following analyses using both CTT and IRT, two of these items were retained.

Cognitive interviewing is an important part of instrument development and item optimization, aiming to ensure that the items and response options are relevant and clear to the target population [

53]. Through cognitive interviewing, items or response options that are difficult to understand can be clarified, and words or terms that may be misunderstood can be identified, thereby enhancing the rigor of the instrument during the adaptation process [

54]. Dickin et al. pointed out that even if the instrument has been translated into the native language, cognitive interviewing still needs to be conducted to ensure that the target population fully understands the items, especially for participants with lower educational levels [

55]. For SPA instruments, it is crucial to accurately capture the real experiences of older adults. If the items do not adequately reflect their actual feelings, it may affect the structural validity and applicability of the instrument. Therefore, listening to the voices of older adults and ensuring that the items reflect their real-life experiences is an indispensable aspect of the questionnaire optimization. This study followed the COSMIN guidelines and conducted three rounds of cognitive interviewing to gain an in-depth understanding of how participants understood the items and the logic of their response selection [

56]. Problems such as inappropriate wording, ambiguity, and redundancy were systematically addressed, aligning the instrument with the language habits and cultural context of community-dwelling older adults in China.

Currently, the C-APQ consists of 32 items, which can comprehensively assess the SPA of older adults in China and has been applied in relevant studies [

24]. However, as a questionnaire with many items, it has limitations in practical applications, such as time consumption and inefficient response rates, so it is necessary to simplify it. Researchers have employed various methods to develop short versions of the original APQ. For example, Sexton et al. deleted the items by identifying overlapping pairs of items based on modified indices, parameter change values, and standardized residual covariance [

25]. Miremadi et al. utilized EFA and CFA for item selection [

28]. Slotman et al. conducted item selection by examining indicators such as local dependence, factor loading, floor effect, and ceiling effect [

27]. In this study, CTT and IRT were employed to screen items. Ultimately, 11 items were removed, resulting in the M-APQ comprising seven dimensions and 24 items. Although this reduction is moderate compared to other short forms, the M-APQ retains all seven dimensions of the original scale. Specifically, except for the emotional representation dimension, which includes six items, each of the other six dimensions (acute/chronic timeline, cyclical timeline, negative control, positive control, negative consequence, and positive consequence) includes three items. This moderate reduction helps avoid excessive loss of important content, ensuring the instrument maintains its theoretical integrity and multidimensional structure.

In practical application, the M-APQ demonstrated good participant acceptability and feasibility. The items of the M-APQ were easy for the participants to understand, and the response rate was high. The time required to complete the M-APQ ranged from 10 to 19 min, which is reasonable and helps avoid interruptions. The number of items is appropriate, which enables comprehensive assessments of the target construct without increasing the excessive burden on participants, further proving the scientific validity and feasibility of the M-APQ. As a result, the M-APQ is easier to use in community settings, which may facilitate broader adoption and improve data quality.

The M-APQ shows good psychometric properties. The CFA results indicate that all fit indices for the seven-factor structure met established psychometric standards, suggesting that the M-APQ possesses a stable and well-defined factor structure. Compared with the B-APQ (five dimensions) [

57] and APQ-P (four dimensions) [

28], the M-APQ includes seven dimensions. This multidimensional structure aligns closely with the theoretical framework of the Common-Sense Model and the original APQ, ensuring that the instrument comprehensively reflects the complex and multifaceted nature of SPA. The results of known-group validity showed significant differences in the scores of each dimension of M-APQ between community-dwelling older adults with different self-rated health statuses. This finding is consistent with theoretical expectations and previous research, showing that older adults with better self-rated health are more likely to possess positive aging perceptions [

58]. In contrast, those with poorer health or multiple chronic conditions are more prone to negative SPA [

59]. These results provide strong evidence for the known-group validity of the M-APQ, confirming its effectiveness in differentiating between population subgroups with varying health statuses.

Convergent validity was assessed by calculating the AVE and CR for each dimension of the M-APQ. The AVE values for all dimensions ranged from 0.572 to 0.685, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.50 [

49], while the CR values ranged from 0.800 to 0.889, surpassing the recommended minimum of 0.70 [

60]. These results provide strong evidence that the items within each dimension of M-APQ share a substantial proportion of common variance, indicating that they consistently measure the same underlying construct. Additionally, the results of the Spearman correlation analyses between SPA and health-related quality of life were consistent with theoretical expectations and previous research findings [

25]. Specifically, older adults who exhibited a stronger awareness of the chronic or cyclical nature of their aging tended to report lower levels of mental health. Conversely, those who perceived aging as having a positive impact on their lives reported higher levels of mental health, supporting the notion that a positive outlook on aging can enhance mental well-being. Furthermore, a greater sense of control over the positive aspects of aging was correlated with better physical health, indicating that perceived agency in managing the aging process may contribute to improved physical health status [

61]. The alignment between observed correlations and existing research findings demonstrates that the M-APQ meaningfully relates to important health outcomes. These findings further reinforce its convergent validity.

Cronbach’s α coefficient is a commonly used indicator for evaluating internal consistency. In this study, all dimensions of the M-APQ demonstrated Cronbach’s α values exceeding 0.70, indicating that both the overall scale and its subdimensions possess acceptable internal consistency. Compared to previous studies, the internal consistency of the M-APQ and its dimensions in this study is relatively good. For example, in the APQ-S, Cronbach’s α for the “cyclical timeline” dimension in the Turkish version [

61] and the “positive control” dimension in the Dutch version [

27] were slightly below the generally accepted threshold, at 0.60 and 0.53, respectively. In the B-APQ, the “emotional representation” dimension in the Malaysian version [

62] and the “positive consequences” dimension in the Persian version [

63] both had α values below 0.70. These variations may be attributed to differences in item content, cultural adaptation, or the number of items within individual dimensions. Therefore, our findings indicate that the M-APQ demonstrates good homogeneity among its items.

The reliability of the M-APQ was further examined using ICC, with all dimensions demonstrating values exceeding 0.700. This result indicates a strong test–retest reliability, suggesting that the scale yields stable and consistent scores when administered at different time points. High ICC values are significant for longitudinal research or repeated assessments, as they confirm that the instrument is not unduly influenced by temporal fluctuations or random error [

47]. Such stability is critical for ensuring that the observed scores reflect actual changes in the self-perceptions of aging rather than measurement error. This level of reliability enhances confidence in the M-APQ’s capacity to accurately monitor changes or stability in aging perceptions over time, supporting its suitability for both research and clinical applications.

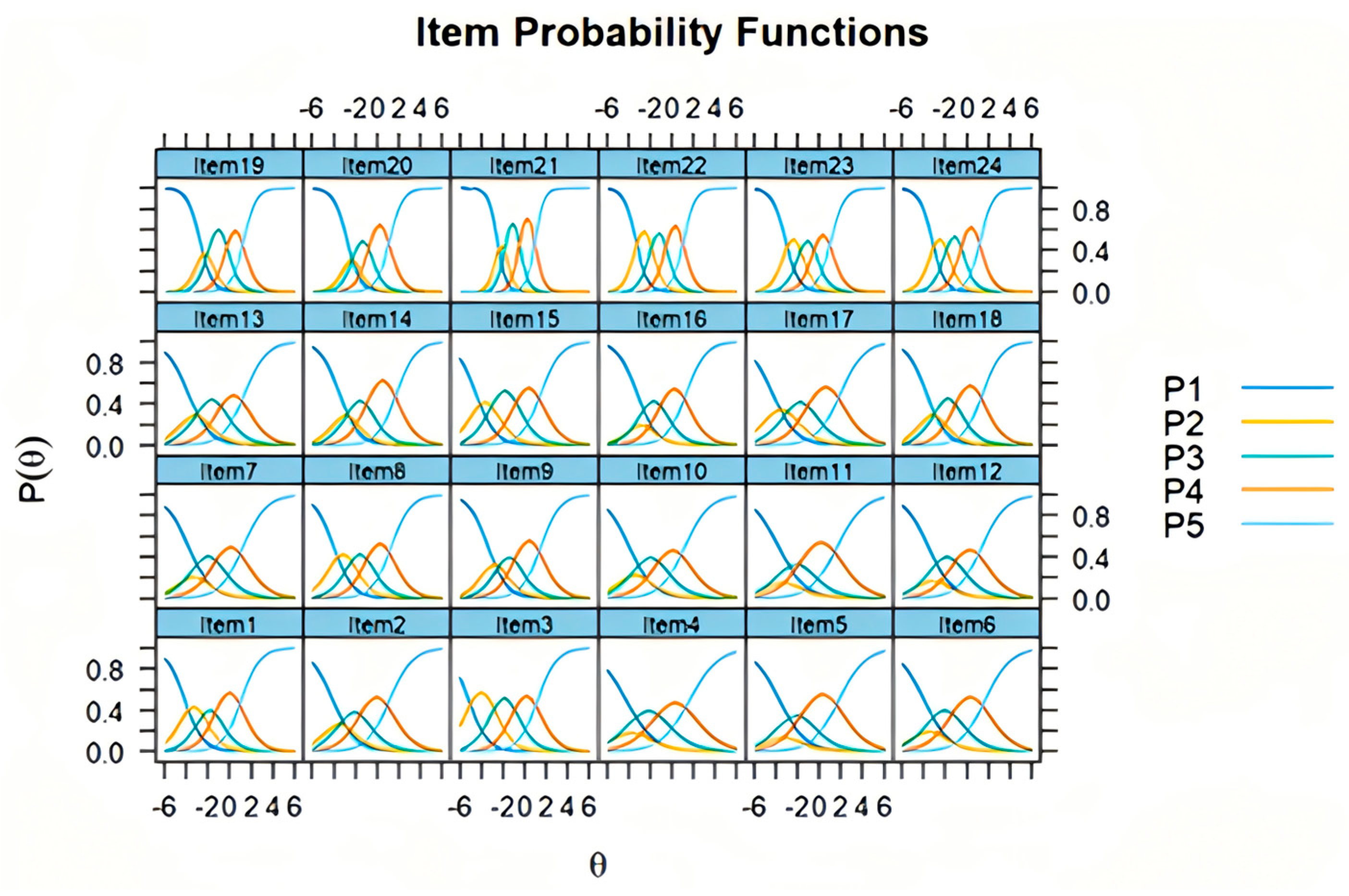

The results of the IRT analysis indicated that the discrimination parameters for all M-APQ items were at a medium or higher level, suggesting that each item can effectively differentiate respondents with varying levels of the latent trait. High discrimination values are important, as they reflect the ability of each item to distinguish subtle differences in SPA among individuals. Moreover, the difficulty parameters for each item exhibited an orderly and increasing progression across response options, with differences between response categories not exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 5 points—a standard considered acceptable in IRT applications [

64]. This finding indicates that the response categories form a well-graded continuum, allowing the scale to capture a broad spectrum of attitudes and perceptions. The distribution of item characteristic curves was also found to be ideal, demonstrating that each item performs consistently and as expected across different latent trait levels. The original APQ and its short forms in various languages have not been evaluated using IRT. IRT provides unique insights into item functioning, such as differential item functioning and measurement precision, which are challenging to uncover with traditional psychometric approaches [

65]. Overall, these IRT findings provide strong evidence for the measurement precision and validity of the M-APQ, further supporting its psychometric soundness for use in both research and applied settings.

Cultural values have an important influence on shaping the SPA of older adults. The newly added item 33 in the “emotional representation” dimension of M-APQ, “As I grow older, I feel increasingly useless,” captures the self-perceived sense of uselessness. This item reflects an individual’s negative self-evaluation of their own and others’ usefulness (such as family, friends, community, or society) and also reflects their overall understanding and acceptance of the aging process [

66]. This cognitive tendency is shaped by personal experiences and the daily living environment [

67]. In Confucian culture, older adults are usually regarded as core family and society members, attaching importance to family and intergenerational relationships, which helps them maintain a positive self-image [

68]. However, as modernization and industrialization progress, the traditional views of filial piety have somewhat diminished. Older persons’ status in family decision-making and social roles may be challenged, and their sense of purpose may be weakened accordingly. Some older adults may internalize these negative views and develop a sense of uselessness [

69]. To provide a comprehensive assessment of older adults’ SPA, instruments need to be adapted to specific cultural and linguistic contexts. For example, during the validation of the APQ short form for older persons with chronic disease, the expert panel suggested that items related to a “sense of uselessness” should be added according to cultural characteristics [

70]. Additionally, Zhao et al. proposed that self-perceived uselessness is an important aspect of SPA [

71]. This view can be traced back to the relevant item in the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale, which has been used to assess SPA in longitudinal studies [

72].

Furthermore, item 35 was added to the emotional representation dimension of M-APQ: “I am worried about becoming a burden to my family due to getting old.” The original expression of this item was “I am worried about becoming a burden to others due to aging.” Participants suggested limiting “others” to “family members” in cognitive interviewing. Qualitative research shows that older adults generally mention that “children have their own little families” and express that they “do not want to cause trouble.” They believe that adult children have taken on work and family responsibilities and should not impose additional burdens by taking care of their parents [

73]. Subsequent research found that when older adults require short-term care, they generally hope for visits from their children, but they do not wish their children to adjust their work and family arrangements due to long-term care for them [

74]. As individuals age, they are more likely to experience declines in their ability to live independently due to health issues or financial challenges, leading to a sense of “being a burden,” especially when they need more family care and support [

75].

4.1. Implications for Healthcare

This study developed a convenient and scientific instrument to assist healthcare professionals and researchers in effectively assessing the SPA level of community-dwelling older adults. Compared with C-APQ, M-APQ also covers seven dimensions and comprehensively reflects the SPA status of older adults. Meanwhile, the number of items is concise, which improves the convenience and efficiency of use.

In practice, the M-APQ can serve as a screening tool during routine geriatric health assessments, enabling healthcare providers to identify older adults with negative SPA and potential risk for adverse physical and mental health outcomes. By analyzing scores across specific dimensions, healthcare providers can pinpoint areas where individuals may have cognitive biases or require additional support and develop tailored intervention programs. For example, older adults with low scores in the “positive control” dimension can be referred to participate in emotional regulation training, problem-solving skills workshops, or programs that strengthen social support networks, thereby improving their capacity to cope positively with aging. For those with high scores in the “Emotional Representation” dimension, priority can be given to psychological counseling, group psychotherapy, or art therapy interventions to alleviate negative emotions and foster a more positive outlook on aging.

At the policy and programmatic level, regular assessment and aggregation of SPA data among community older adults allow administrators to monitor population-level trends in SPA. This evidence can guide the optimal allocation of public health resources and inform the design and implementation of targeted health promotion and mental health support initiatives, ultimately advancing healthy aging goals.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study lies in its systematic and rigorous optimization process of the instrument. Through qualitative research exploring the concept connotation of SPA among community-dwelling older adults, three new items were added to the C-APQ. Following three rounds of cognitive interviewing, the items were revised based on participant feedback to address potential comprehension differences, ensuring that the semantics of the items remained consistent with the original APQ. The items were screened using a combination of CTT and IRT, ultimately resulting in the formation of the M-APQ, and its psychometric properties were further verified.

However, this study has some limitations. The data for the questionnaire survey were collected in the Chongqing area, and participants were recruited through convenience sampling, which may limit the generalizability of the results. To determine the applicability of these findings to other regions, further validation through multi-center studies and larger sample sizes is needed. Additionally, not all psychometric properties mentioned in the COSMIN guidelines were assessed. Future studies should evaluate the criterion validity of M-APQ by comparing it with C-APQ and adopt longitudinal study designs to assess its responsiveness to further verify the scientific nature of M-APQ.