The Role of Education in Emotional Intelligence to Perceive, Understand and Regulate Emotions: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

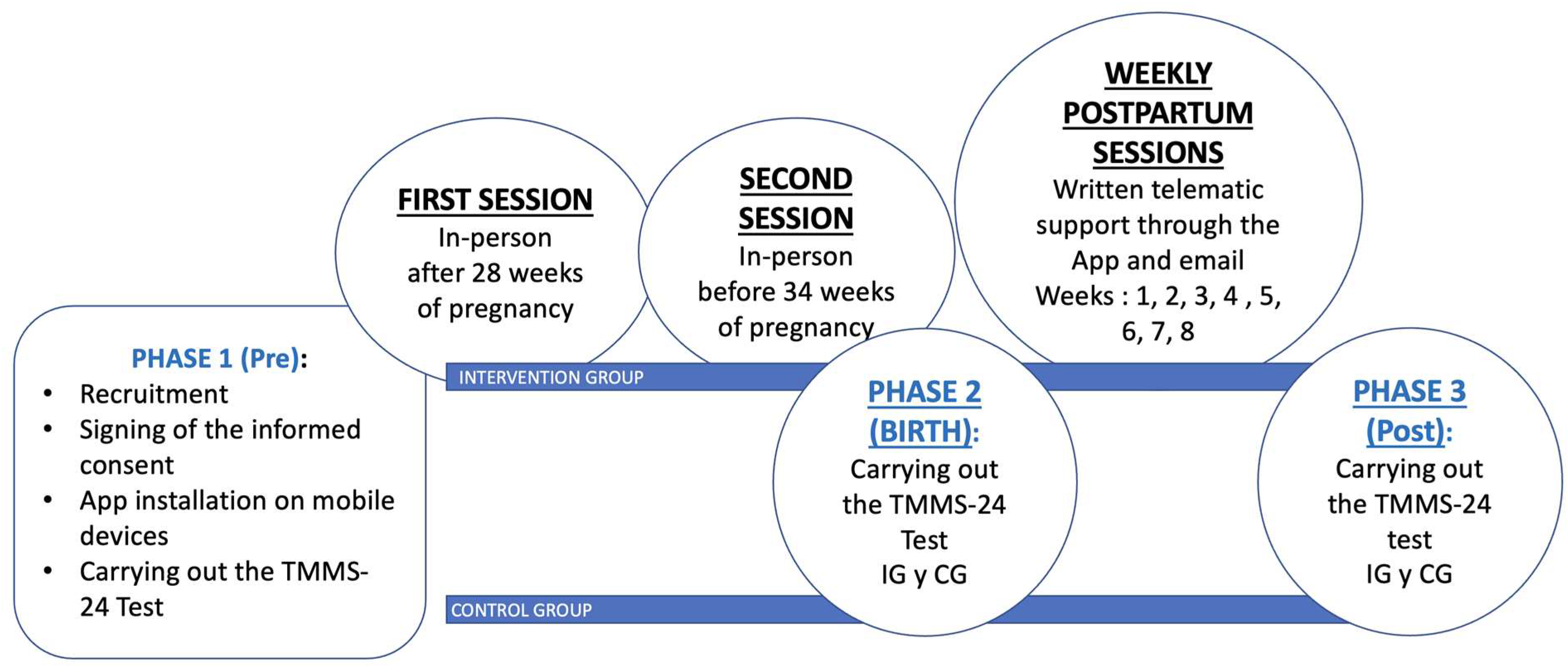

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Intervention

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Population

2.5. Sample Size Calculation

3. Measures

3.1. Maternal Characteristics Variables

3.2. Emotional Intelligence

3.3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Description of the Sample

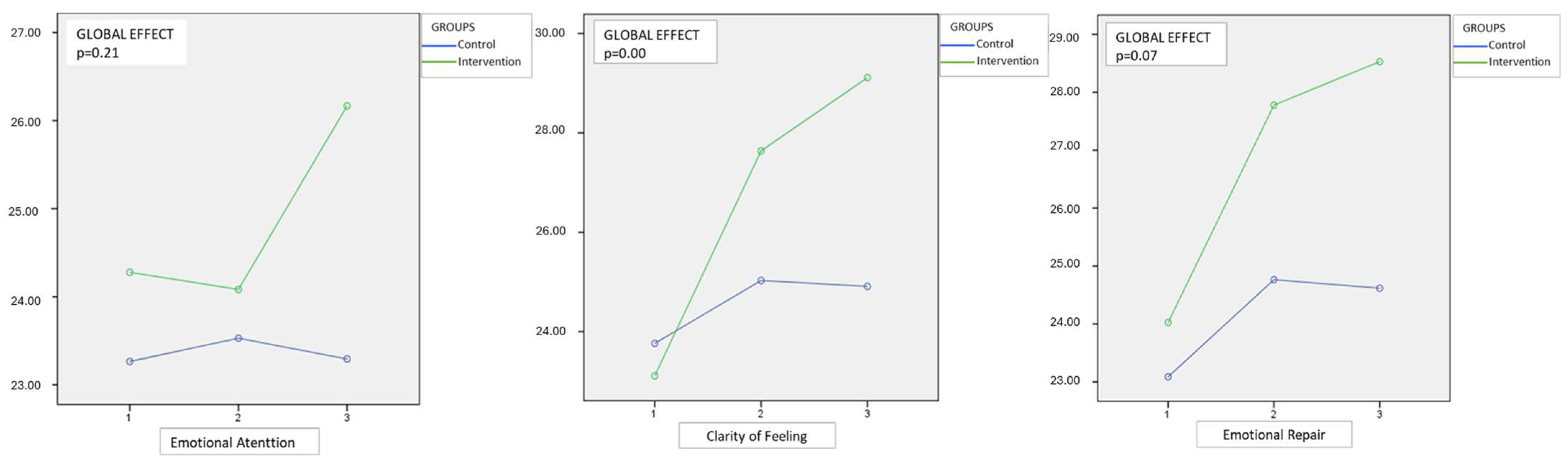

4.2. Effect of the Intervention

5. Discussion

5.1. Dimensions or Domains of the Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire (TMMS 24)

5.2. Relationship with Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

5.3. Relationship Between the Different Phases of the Study

6. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patanella, D.; Ebanks, C. Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences. In Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development; Goldstein, S., Naglieri, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychoprophylactic Intervention Program Based on Emotional Intelligence, Aimed at the Dimension of Safe Motherhood (Pregnancy Home); University of Cundinamarca: Fusagasugá, Colombia, 2019.

- Alonso-Serna, D. Emotional Intelligence, Daniel Goleman. Con-Ciencia Serrana Scientific Bulletin of the Ixtlahuaco Preparatory School. 2019. Available online: https://repository.uaeh.edu.mx/revistas/index.php/ixtlahuaco/article/view/3677 (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Douaihy, A.; Rivet Amico, K. Motivational Interviewing in HIV Care; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, S.; Haddad, C.; Fares, K.; Malaeb, D.; Sacre, H.; Akel, M.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. Correlates of emotional intelligence among Lebanese adults: The role of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, alcohol use disorder, alexithymia and work fatigue. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, L.; Prado- Gascó, V.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Longitudinal analysis of subjective well-being in preadolescents: The role of emotional intelligence, self-esteem and perceived stress. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simó, S.; Zúñiga, L.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Rodrigo, M.F. Effects of ultrasound on anxiety and psychosocial adaptation to pregnancy. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2019, 22, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlisides-Henry, R.D.; Deboeck, P.R.; Grill-Velasquez, W.; Mackey, S.; Ramadurai, D.K.A.; Urry, J.O.; Neff, D.; Terrell, S.; Gao, M. Behavioral and physiological stress responses: Within-person concordance during pregnancy. Biol. Psychol. 2021, 159, 108027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, M.; Ozturk, F. Qualitative Research in Social Sciences: A Research Profiling Study. Educ. Policy Anal. Strateg. Res. 2022, 17, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Cruz, F. Anxiety, Depression and Stress as Risk Factors for Threatened Preterm Birth at the Support Hospital II—Sullana in the Years 2019–2020; Previous Private University Orrego: Trujillo, Peru, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bohórquez, A.; Lemos, M. Anxiety, Depression and Associated Demographic Characteristics in Pregnancy in Women Between 14 and 40 Years of Age in the Metropolitan Area of the Aburrá Valley; EAFIT University: Medellín, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, A.; Thomas, H.; Brooks, F. In labor or in limbo? The experiences of women undergoing induction of labor in hospital: Findings of a qualitative study. Birth 2018, 45, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, K.K.; Riley, L.; Castro, V.M.; Perlis, R.H.; Kaimal, A.J. Association of Antenatal Depression Symptoms and Antidepressant Treatment With Preterm Birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 127, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health 2019, 15, 174550651984404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, B.R. Fetal programming: Prenatal growth and development environment, by Rafael A. Caparrós González. Ediciones Pirámide, 231 pp., year 2019. Clin. Salud 2021, 32, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loughlin, K.; Althoff, R.; Hudziak, J. Health promotion and prevention in child and adolescent mental health. (Irarrazaval M, Martin A eds. Prieto-Tagle F, Elias N trans.). In King JM (ed). IACAPAP Child Adolesc. Ment. Health Man. 2018, 14, 2–28. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Acosta, K. Eight Mental Health Studies; Caribbean University Corporation: Bayamón, Puerto Rico, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apter-Levy, Y.; Feldman, M.; Vakart, A.; Ebstein, R.P.; Feldman, R. Impact of Maternal Depression Across the First 6 Years of Life on the Child’s Mental Health, Social Engagement, and Empathy: The Moderating Role of Oxytocin. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, S.L.; Mitchell, A.M.; Kowalsky, J.M.; Christian, L.M. Maternal parity and perinatal cortisol adaptation: The role of pregnancy-specific distress and implications for postpartum mood. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 97, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flórez-García, V.; Rojas-Bernal, L.Á.; Bareño-Silva, J. Depression and sleep disorders related to arterial hypertension: A cross-sectional study in Medellín, Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Psiquiatr. 2020, 49, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.; Stevenson, E.; Moeller, L.; McMillian-Bohler, J. Systematic Screening for Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders to Promote Onsite Mental Health Consultations: A Quality Improvement Report. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2021, 66, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoville, A.; Duncan, S. Why is Mom So Blue? Postpartum Depression in a Family Context. ForeverFamilies 2018, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Dadi, A.F.; Miller, E.R.; Bisetegn, T.A.; Mwanri, L. Global burden of prenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Romero, E.; Flórez -García, V.; Egede, L.E.; Yan, A. Factors associated with the double burden of malnutrition at the household level: A scoping review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 6961–6972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Ng, E.D.; Wong, C.H.J. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 61, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míguez, M.; Fernández, V.; Pereira, B. Postpartum depression and associated risk factors among women with risk pregnancies. Psycho Conduct 2017, 25, 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero, E. Influence of Social Determinants on the Emotional Health of Pregnant Adolescents at the Morales Health Center; National University of San Martín: San Martín, Argentina, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Giovanazzi, S.; Pérez, A. Design of a regression model to predict the presence of depression during pregnancy based on emotional intelligence, parental care, anxiety and stress. Interactions 2023, 9, e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olza, I.; Fernández, P. Psychology of Pregnancy from a Systemic Perspective; Norte de Salud Mental: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McKeough, R.; Blanchard, C.; Piccinini-Vallis, H. Pregnant and Postpartum Women’s Perceptions of Barriers to and Enablers of Physical Activity During Pregnancy: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D.; Goldman, S.; Turvey, C.; Palfai, T. Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, Disclosure, and Health; Pennebaker, J.W., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Núñez, M.I.; Torregrosa, M.S.; Inglés, C.J.; Lagos San Martín, N.G.; Sanmartín, R.; Vicent, M.; García-Fernández, J.M. Factor Invariance of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale–24 in a Sample of Chilean Adolescents. J. Personal. Assess. 2020, 102, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Modified Version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extremera, N.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction: Predictive and incremental validity using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005, 39, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taramuel, J.; Zapata, V. Application of the TMMS-24 test for the analysis and description of Emotional Intelligence considering the influence of sex. Publishing 2017, 4, 162–181. [Google Scholar]

- Galdiolo, S.; Gaugue, J.; Mikolajczak, M.; Van Cappellen, P. Development of Trait Emotional Intelligence in Response to Childbirth: A Longitudinal Couple Perspective. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 560127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoç, H.; Mucuk, Ö.; Özkan, H. The Relationship of Emotional Intelligence and Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy in Mothers in the Early Postpartum Period. Breastfeed. Med. 2020, 15, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molero Jurado Mdel, M.; Pérez-Fuentes Mdel, C.; Oropesa Ruiz, N.F.; Simón Márquez Mdel, M.; Gázquez Linares, J.J. Self-Efficacy and Emotional Intelligence as Predictors of Perceived Stress in Nursing Professionals. Medicine 2019, 55, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Extremera, N.; Fernandez, P. Perceived emotional intelligence and individual differences in meta-knowledge of emotional states: A review of studies with the TMMS. Anxiety Stress 2005, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraza López, R.; Heise Burgos, D.; Giovanazzi Retamal, S. Relación entre niveles de depresión, inteligencia emocional percibida y percepción de cuidados parentales en embarazadas/Relationship between depression depression levels, perceived emotional intelligence and perception of parental care in pregnancy. Liminales Mag. Writ. About Psychol. Soc. 2015, 4, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, J.; Mu, L.; Ye, Z. Preventing Postpartum Depression With Mindful Self-Compassion Intervention. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2020, 208, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control Group | Group Intervention | TOTAL | p Value * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 34 (%) | n = 35 (%) | n = 71 (%) | |||

| (Year old) | |||||

| <30 | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 18 (26.1) | 0.03 | |

| > =30 | 22 (43.1) | 29 (56.9) | 51 (73.9) | ||

| Education level | |||||

| Secondary studies | 3 (8.8) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (5.8) | 0.03 | |

| University Studies | 8 (23.5) | 7 (20) | 15 (21.7) | ||

| Professional education | 5 (14.7) | 1 (2.9) | 6 (8.7) | ||

| Advanced Professional Education | 6 (17.6) | 1 (2.9) | 7 (10.1) | ||

| Postgrads studies | 9 (26.5) | 21 (60) | 30 (43.5) | ||

| NC | 3 (8.8) | 4 (11.4) | 7 (10.1) | ||

| Nationality | |||||

| Spain | 31 (91.2) | 31 (88.6) | 62 (89.9) | 0.41 | |

| France | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Italy | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Romania | 3 (8.8) | 1 (2.9) | 4 (5.8) | ||

| Venezuela | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Type of delivery | |||||

| Cesarean section | 7 (20.6) | 7 (20) | 14 (20.3) | 0.88 | |

| Eutocic vaginal delivery | 24 (70.6) | 26 (74.3) | 50 (72.5) | ||

| Instrumental | 3 (8.8) | 2 (5.7) | 5 (7.2) | ||

| Type of Anesthesia | |||||

| Spinal | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | 0.66 | |

| Epidural | 26 (76.5) | 30 (85.7) | 56 (81.2) | ||

| General | 2 (5.9) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | ||

| None | 4 (11.8) | 3 (8.6) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Previous Children | |||||

| 0 | 22 (64.7) | 26 (74.3) | 48 (69.6) | 0.67 | |

| 1 | 11 (32.4) | 8 (22.9) | 19 (27.5) | ||

| 2 | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Conception type | |||||

| In vitro | 0 (0) | 2 (5.7) | 2 (2.9) | 0.16 | |

| Natural | 34 (100) | 33 (94.3) | 67 (97.1) | ||

| EB in previous children | |||||

| No | 3 (23.1) | 4 (40) | 7 (30.4) | 0.38 | |

| Yes | 10 (76.9) | 6 (60) | 16 (69.6) | ||

| Gestation weeks | |||||

| 36–40 | 29 (58) | 21(42) | 50 (72.46) | 0.05 | |

| 41–42 | 6 (31.6) | 13 (68.4) | 19 (27.53) | ||

| Coexistence as a Couple | |||||

| NC | 2 (5.9) | 7 (19.4) | 3 (4.3) | 0.34 | |

| No | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Yes | 31 (91.2) | 34 (97.1) | 65 (94.2) | ||

| Has help in parenting | |||||

| NC | 2 (5.9) | 3 (8.6) | 5 (7.2) | 0.11 | |

| No | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (5.8) | ||

| Yes | 28 (82.4) | 32 (91.4) | 60 (87) | ||

| Couple Support | |||||

| NC | 3 (8,8) | 3 (8.6) | 6 (8.7) | 0.11 | |

| No | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 4 (5.8) | ||

| Yes | 27 (79.4) | 32 (91.4) | 59 (85.5) | ||

| Support for family members | |||||

| NC | 3 (8,8) | 4 (11.4) | 7 (10.1) | 0.65 | |

| No | 10 (29.4) | 7 (20) | 17 (24.6) | ||

| Yes | 21 (61.8) | 24 (68.6) | 45 (65.2) | ||

| External Support | |||||

| NC | 3 (8.8) | 5 (14.3) | 8 (11.6) | 0.69 | |

| No | 22 (64.7) | 23 (65.7) | 45 (65.2) | ||

| Yes | 9 (26.5) | 7 (20) | 16 (23.2) | ||

| Newborn sex | |||||

| Female | 20 (58.8) | 15 (42.9) | 35 (50.7) | 0.19 | |

| Male | 14 (41.2) | 20 (57.1) | 34 (49.3) | ||

| Questionnaire TMMS-24 | Control Group | Intervention Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 34 (Half of) | 95% CI | n = 35 (Half of) | 95% CI | |

| Emotional Care–Pre | 23.26 (5.09) | 21.55; 24.98 | 24.26 (5.10) | 22.57; 25.95 |

| Emotional Care–Birth | 23.53 (5.89) | 21.55; 25.51 | 24.03 (4.82) | 22.43; 25.62 |

| Post-Emotional Care | 23.29 (5.14) | 21.57; 25.01 | 26.03 (6.08) | 24.01; 28.04 |

| Clarity of feelings–Pre | 23.76 (5.35) | 21.96; 25.53 | 23.29 (5.88) | 21.34; 25.23 |

| Clarity of feelings–Birth | 23.03 (5.50) | 23.18; 26.87 | 27.66 (6.437) | 25.51; 29.80 |

| Clarity of feelings–Post | 24.91 (6.67) | 22.67; 27.12 | 29.20 (6.36) | 27.09; 31.31 |

| Emotional Repair–Pre | 23.09 (6.11) | 21.04; 25.15 | 24.20 (4.56) | 22.69; 25,713 |

| Emotional Repair–Birth | 24.76 (6.29) | 22.65; 26.86 | 27.74 (5.89) | 25.79; 29.70 |

| Post-Emotional Repair | 24.62 (7.04) | 22.25; 26.93 | 28.43 (5.58) | 26.58; 30.28 |

| QuestionnaireTMMS-24 | Control Group | Group Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -Pre Birth | Post-Pre | Post-Birth | -Pre Birth | Post-Pre | Post-Birth | |

| Mean Difference (p Value) | Mean Difference (Value p) | Mean Difference (Value p) | Mean Difference (Value p) | Mean Difference (Value p) | Mean Difference (Value p) | |

| Emotional Attention | 0.26 (0.75) | 0.03 (0.97) | −0.24 (0.71) | −0.23 (0.77) | 1.77 (0.09) | 2 (0.02) |

| Clarity of Feelings | 1.26 (0.06) | 1.15 (0.24) | −0.12 (0.89) | 4.37 (<0.001) | 5.91 (<0.001) | 1.54 (0.03) |

| Emotional Repair | 1.68 (0.03) | 1.53 (0.11) | 0.15 (0.84) | 3.54 (<0.001) | 4.23 (0.001) | 0.69 (0.44) |

| TMMS-24 Quiz | Differences Between Groups at Different Times | Magnitude of the Effect. Interaction Between Groups by Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net Differences | |||||

| -Pre Birth | Post-Pre | Post-Birth | Partial Squared (ηp2) | p-Value | |

| Significant Difference; Eta2; (p Value) | Significant Difference; Eta2; (p Value) | Significant Difference; Eta2; (p Value) | |||

| Emotional Attention | −0.49; 0.003; (0.66) | 1.74; 0.02; (0.09) | −2.24; 0.06; (0.00) | 0.024 | 0.21 |

| Clarity of Feelings | 3.11; 0.09; (0.01) | 4.77; 0.14; (0.00) | 1.66; 0.03; (0.13) | 0.15 | 0.00 |

| Emotional Repair | 1.87; 0.04; (0.11) | 2.70; 0.05; (0.06) | 0.83; 0.00; (0.47) | 0.05 | 0.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Évora-Lebrero, S.; Bustos-Sepúlveda, M.; Bustos-Sepúlveda, L.; Segura-Fragoso, A.; Florez-Garcia, V.; Gondwe, K.W.; Santacruz-Salas, E. The Role of Education in Emotional Intelligence to Perceive, Understand and Regulate Emotions: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131542

Évora-Lebrero S, Bustos-Sepúlveda M, Bustos-Sepúlveda L, Segura-Fragoso A, Florez-Garcia V, Gondwe KW, Santacruz-Salas E. The Role of Education in Emotional Intelligence to Perceive, Understand and Regulate Emotions: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(13):1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131542

Chicago/Turabian StyleÉvora-Lebrero, Silvia, Marta Bustos-Sepúlveda, Lluvia Bustos-Sepúlveda, Antonio Segura-Fragoso, Victor Florez-Garcia, Kaboni Whitney Gondwe, and Esmeralda Santacruz-Salas. 2025. "The Role of Education in Emotional Intelligence to Perceive, Understand and Regulate Emotions: A Quasi-Experimental Study" Healthcare 13, no. 13: 1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131542

APA StyleÉvora-Lebrero, S., Bustos-Sepúlveda, M., Bustos-Sepúlveda, L., Segura-Fragoso, A., Florez-Garcia, V., Gondwe, K. W., & Santacruz-Salas, E. (2025). The Role of Education in Emotional Intelligence to Perceive, Understand and Regulate Emotions: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare, 13(13), 1542. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131542

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)