Impact of a Multidimensional Community-Based Intervention on the Feeling of Unwanted Loneliness and Its Consequences: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Increasing the number of opportunities for social interaction during the intervention;

- Contributing tools to improve the participants’ social skills in the intervention;

- Fostering self-care and healthy habits in the participants;

- Reducing maladaptive thoughts;

- Educating on sleep hygiene measures and non-pharmacological treatments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sampling Method

2.2. Study Setting

- Santa Cruz de La Palma Basic Health District (Santa Cruz de La Palma Health Centre, Puntallana Local Medical Office);

- Las Breñas Basic Health District (Breña Alta Health Centre, Breña Baja Local Medical Office);

- Mazo Basic Health District (Mazo Health Centre, Fuencaliente Local Medical Office);

- El Paso Basic Health District (El Paso Health Centre, Las Manchas Local Medical Office);

- Los Llanos de Aridane Basic Health District (Llanos de Aridane Health Centre);

- Tazacorte Basic Health District (Tazacorte Health Centre, Puerto Tazacorte Local Medical Office);

- Tijarafe Basic Health District (Tijarafe Health Centre, Puntagorda Local Medical Office);

- Garafía Basic Health District (Garafía Health Centre, Los Franceses Local Medical Office);

- San Andrés y Sauces Basic Health District (San Andrés Health Centre, Barlovento Local Medical Office, Gallegos Local Medical Office).

2.3. Nursing Intervention Design and Preparation

2.4. Variables

2.4.1. Main Variable

- -

- Feeling of unwanted loneliness. This was measured using the “UCLA (University of California at Los Angeles) Loneliness Scale” test validated in Spain. This instrument is based on three dimensions: relational connection, social connection, and self-perceived isolation. It uses a 4-point scale ranging from “never” to “frequently.” The 10-item version (a shortened version of the original 20-item version) was used, which has been translated to, adapted to, and validated for Spanish. Scores above 30 correspond to “no loneliness,” between 20 and 30 mean “moderate loneliness,” and less than 20 points is “severe loneliness” [29].

2.4.2. Secondary Variables

- -

- Social risk. This was measured using the Gijón Social Risk Detection questionnaire. It assesses family and economic situations, housing, social relations, and support from social networks. It uses a 5-point scale ranging from best to worse situation for responses to 5 items. Scores are as follows: good/acceptable social situation: from 5 to 9 points, social risk: from 10 to 14 points, and social problem: more than 15 points [30].

- -

- Perceived social support. This was measured with Duke’s questionnaire. It assesses perceived social support and consists of 11 items, each one assessed with a Likert scale from 1 to 5. Scores equal to or higher than 32 indicate “normal support,” whereas less than 32 points means “low perceived social support” [31].

- -

- Anxiety and depression. These were assessed using Goldberg’s questionnaire with two subscales: Anxiety and Depression. Each of them is structured with 4 initial screening items to determine the probability of a mental disorder and a second group with 5 items that are only formulated if positive answers are given to the screening questions (at least 2 in the Anxiety subscale and at least 1 in the Depression subscale). The type of response of the questionnaire is dichotomous (Yes/No). The cut-off points are as follows: scores equal to or higher than 4 for the Anxiety subscale, and values equal to or higher than 2 for Depression. In the geriatric population, it has been proposed to use it as a single scale, with a cut-off point equal to or higher than 6 [32].

- -

- Social support (Yes/No). This included belonging to an organized group, being integrated in the area where they live, having a support network, participating in activities in free and/or leisure time, having a caregiver, and having support people.

- -

- Defining characteristics for risk of loneliness and for social isolation (Yes/No). These included affective deprivation, emotional deprivation, physical isolation, social isolation, low social activity levels, change in physical aspect, explicit dissatisfaction with social connections, social reclusion, social behavior inconsistent with cultural norms, reporting feeling insecure in public, and reduced eye contact.

- -

- Variables related to lifestyle habits. These included eating habits, physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and sleep (sleep problem; restful sleep; naps).

2.4.3. Sociodemographic Variables

- -

- These included gender, marital status, age, housing arrangement: unipersonal, home-based care, social assistance, architectonic barriers, and alteration in any sensory capability.

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

3.2. Pre-Intervention Analysis

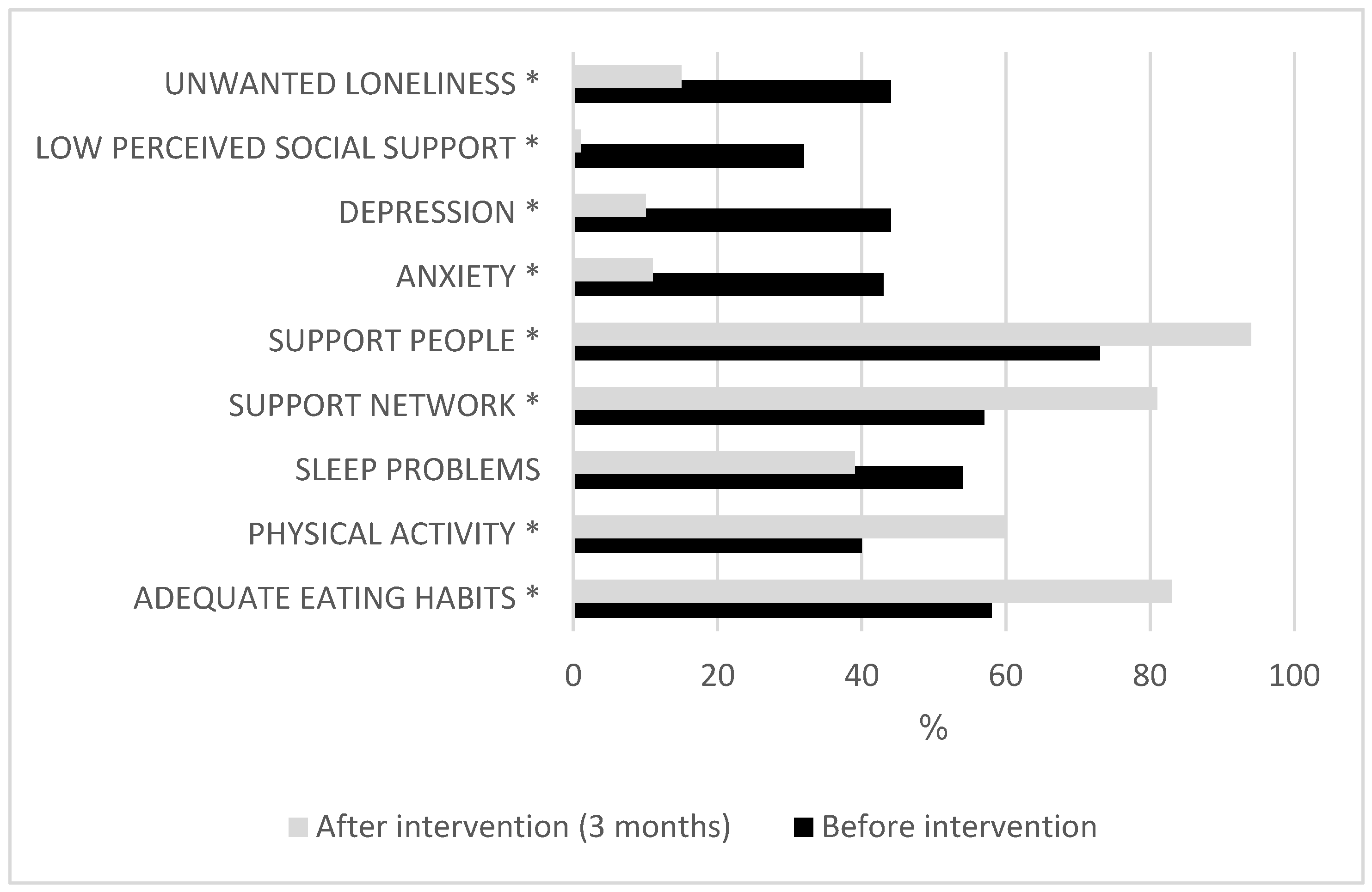

3.3. Post-Intervention Analysis

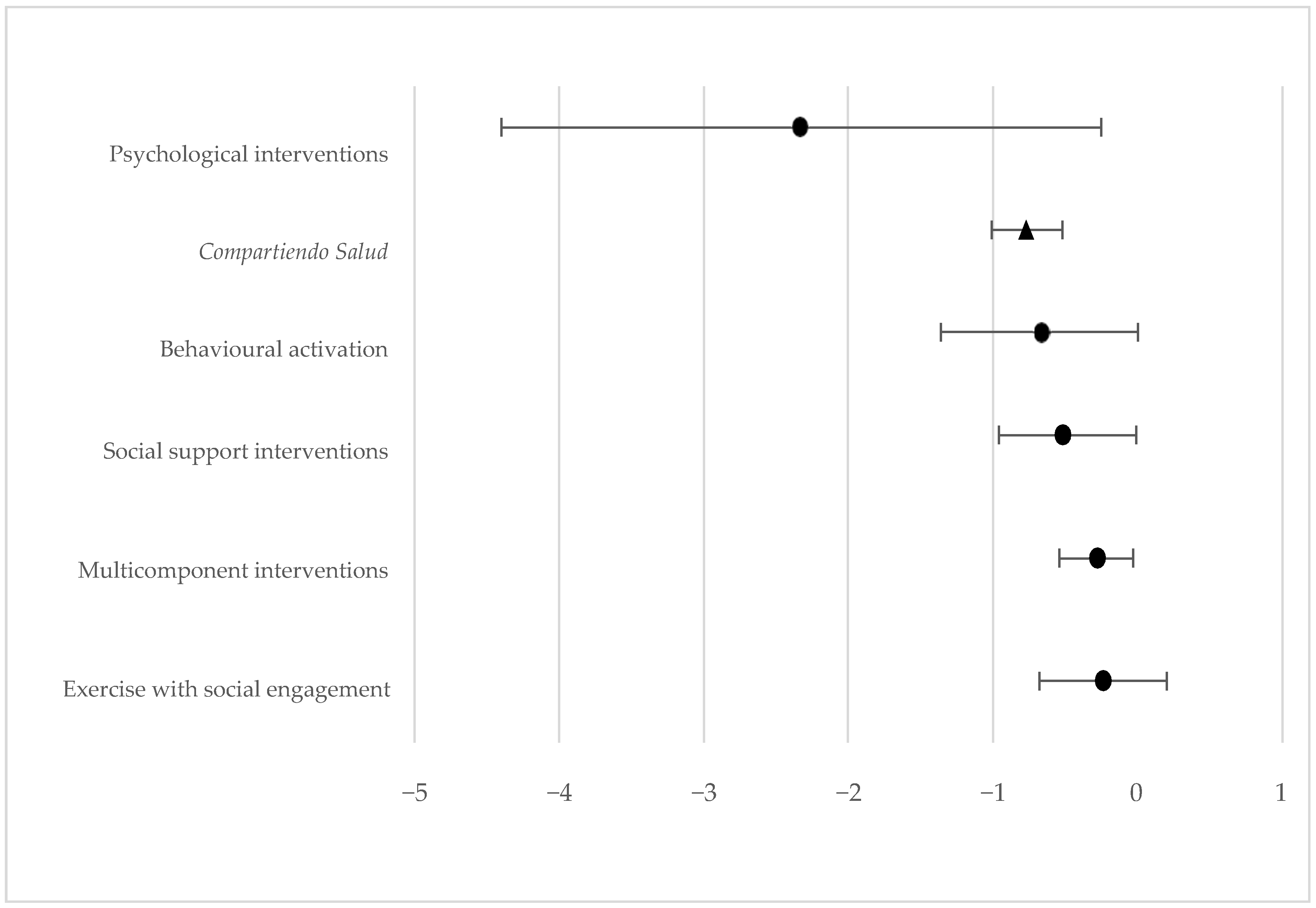

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). National Statistics Institute. Available online: https://www.ine.es/ (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Surkalim, D.L.; Luo, M.; Eres, R.; Gebel, K.; van Buskirk, J.; Bauman, A.; Ding, D. The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 376, e067068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, K.; Victor, C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 1368–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luanaigh, C.O.; Lawlor, B.A. Loneliness and the health of older people. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakoya, O.A.; McCorry, N.K.; Donnelly, M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gené-Badia, J.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.; Obiols-Masó, N.; Oliveras Puig, L.; Lagarda Jiménez, E. Social isolation and loneliness: What can primary care teams do? Aten. Primaria 2016, 48, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M.; Owens, J. A meta-analysis of loneliness and use of primary health care. Health Psychol. Rev. 2023, 17, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzen, E.; Çikrikci, Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, I.H.; Conwell, Y.; Bowen, C.; Van Orden, K.A. Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peplau, L.A.; Perlman, D. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- CEINe. Community Action: A Tool for the Prevention of Loneliness and Social Isolation Among Older People, 1st ed.; CEINe: Madrid, Spain, 2025; p. 50. Available online: https://cenie.eu/sites/default/files/Informe-final-soleidad.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- SoledadES National Observatory of Unwanted Loneliness. Barometer of Unwanted Loneliness in Spain 2024. Available online: https://www.soledades.es/ (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Chan, A.W.; Yu, D.S.; Choi, K.C. Effects of tai chi qigong on psychosocial well-being among hidden elderly, using elderly neighborhood volunteer approach: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barcelona City Council. Municipal Strategy Against Loneliness. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/dretssocials/es/barcelona-contra-la-soledad/estrategia-municipal-contra-la-soledad (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- SoledadES Enréd@te Programme. Available online: https://www.soledades.es/inspiracion/iniciativas/programa-enredate (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Yu, D.S.; Li, P.W.; Lin, R.S.; Kee, F.; Chiu, A.; Wu, W. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on loneliness among community dwelling older adults: A systematic review, network meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 144, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, L.; McKee, K.J. Correlates of social and emotional loneliness in older people: Evidence from an English community study. Aging Ment. Health 2013, 18, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharia, G.; Ibáñez-del Valle, V.; Cauli, O.; Corchón, S. The Long-Lasting Effect of Multidisciplinary Interventions for Emotional and Social Loneliness in Older Community-Dwelling Individuals: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 3847–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo-Peralta, L.P.; Sánchez-Moreno, E.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, V.; García Martín, M. La investigación sobre soledad y redes de apoyo social en las personas mayores: Una revisión sistemática en Europa [Studying loneliness and social support networks among older people: A systematic review in Europe]. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2023, 97, e202301006. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de la Iglesia, J.; Dueñas Herrero, R.; Onís Vilches, M.C.; Aguado Taberné, C.; Albert Colomer, C.; Luque Luque, R. Spanish Language Adaptation and Validation of the Pfeiffer’s Questionnaire (SPMSQ) to Detect Cognitive Deterioration in People Over 65 Years of Age. Med. Clin. 2001, 117, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Lyles, C.; Crepaz, N.; The Trend Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Palma Health Services Management Office. Canary Islands Health Service. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/sanidad/scs (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Herdman, T.H.; Kamitsuru, S.; Takáo Lopes, C. Nursing Diagnoses. Definitions and Classification 2021–2023, 12th ed.; Thieme: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, M. Nursing Diagnosis: Process and Application, 3rd ed.; Mosby: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Velarde-Mayol, C.; Fragua-Gil, S.; García-de-Cecilia, J.M. Validation of the UCLA Loneliness Scale in an Elderly Population Living Alone. Semergen 2016, 42, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Palacios, M.; Domínguez Puente, O.; Toyos García, G. Results from the Application of a Socio-Familial Assessment Scale in Primary Care. Rev. Esp. Geriatr. Gerontol. 1994, 29, 239–245. [Google Scholar]

- Bellón Saameño, J.A.; Delgado Sánchez, A.; Luna del Castillo, J.D.; Lardelli Claret, P. Validity and Reliability of the Duke-UNC-11 Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Aten. Primaria 1996, 18, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Pérez-Echeverría, M.J.; Artal, J. Validity of the scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) in a Spanish population. Psychol. Med. 1986, 16, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, R. Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Yan, X.; Ren, Z.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Jin, X. Association between insomnia and frailty in older population: A meta-analytic evaluation of the observational studies. Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Larsen, R.T.; Korfitsen, C.B.; Juhl, C.B.; Andersen, H.B.; Christensen, J.; Langberg, H. The MIPAM trial: A 12-week intervention with motivational interviewing and physical activity monitoring to enhance the daily amount of physical activity in community-dwelling older adults—A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanchez, A.; Bully, P.; Martinez, C.; Grandes, G. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion interventions in primary care: A review of reviews. Prev. Med. 2015, 76, S56–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daskalopoulou, C.; Stubbs, B.; Kralj, C.; Koukounari, A.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Physical activity and healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 38, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Subdirección General de Información Sanitaria. Mental Health in Data: Prevalence of Mental Health Problems and Consumption of Psychotropic Drugs and Related Medications Based on Primary Care Clinical Records, BDCAP Series 2; Ministry of Health: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- Zhang, X.; Dong, S. The relationships between social support and loneliness: A meta-analysis and review. Acta Psychol. 2022, 227, 103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gené-Badia, J.; Comice, P.; Belchín, A.; Erdozain, M.Á.; Cáliz, L.; Torres, S.; Rodríguez, R. Loneliness and Social Isolation Profiles in Urban Populations. Aten. Primaria 2020, 52, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Alonso, J.; Bueno Pérez, A.; Toraño Ladero, L.; Caballero, F.F.; López García, E.; Rodríguez Artalejo, F.; Lana, A. Hearing Loss and Social Frailty in Older Men and Women. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concepts | Dynamics |

|---|---|

| Sleep hygiene | |

| Importance of resting What is sleep? Conditioning factors Naps Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments Sleep hygiene, sleep and eating habits Sleep and physical exercise Relaxation techniques | Presentation with the ball Brainstorming: “Is it important to sleep?” Videos explaining the “7Ds” method When is it best to eat this food? To wake up or to go to bed? True or false Jacobson’s progressive muscle relaxation technique |

| Healthy and sustainable eating habits | |

| Importance of eating habits The “5S” of eating habits Food groups What to buy? Label reading Harvard plate | Presentation with the ball Identifying hidden spices What to buy? How much sugar is in this product? We create our meal. “Re-cipe me”: turning an unhealthy recipe into a healthy one |

| Physical activity and exercise | |

| Benefits of physical activity Types of physical exercise Warming up Adapted balance, resistance, strengthening, and flexibility exercises Stretching | Presentation with the ball Warming up Circuit including balance, resistance, strength, and flexibility exercises Ring game Stretching |

| Memory and music therapy | |

| Long- and short-term memory exercises Auditory and audiovisual memory activities Calculation, attention, and language exercises | Presentation with the ball Recalling old-time games and sayings Recalling series of numbers and words Identifying and recalling the highest possible number of elements from an image for 30 s Matching a person’s name with their photograph (actors/actresses, presenters, singers, public figures) Double-card game; searching for the match Replicating a geometrical shape Calculation exercise Listing a group of words without repeating those already mentioned Filling in the lyrics of a song with missing words Drawing a sketch representing a movie or a song for the rest of the group to guess Drama is your cup of tea: using mime to try and represent the lyrics of a song for the others to identify which song it is Playing “Color Esperanza” (“The Color of Hope”) and “Madre Tierra” (“Mother Earth”) and representing their lyrics with body movements |

| Digital literacy | |

| Format adjustments Connecting to a Wi-Fi network Using instant messages Using video calls, searching on the Internet Recording events and appointments in a calendar Listening to music Emergency contact “Mi Cita Previa,” “Mi Historia Clínica,” and “TILP” apps; taking photographs; and recording video | Presentation with the ball Explaining the different sections of the contents, helping the participants do it with their cell phones We downloaded apps that ease their management, such as those available in the SCS and the ones they requested. |

| Variable (Score) * | d | g | r | Mdn Mdn Before After | Rg Neg | Rg Pos | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | −0.77 | −0.77 | 0.65 | 32 | 37 | 274 | 2,355 | −5.8 | <0.001 ** |

| Anxiety | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 2 | 0 | 1,768 | 249 | −5.2 | <0.001 ** |

| Depression | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.55 | 1 | 0 | 1,181 | 146 | −4.9 | <0.001 ** |

| % After | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % Before | No | Yes | T | p * |

| Adequate eating habits | No | 6 | 36.1 | 42.2 | 0.001 ** |

| Yes | 10.8 | 47 | 57.8 | ||

| T | 16.9 | 83.1 | 100 | ||

| Physical activity | No | 30.1 | 30.1 | 60.2 | 0.005 ** |

| Yes | 9.6 | 30.1 | 39.8 | ||

| T | 39.8 | 60.2 | 100 | ||

| Sleep problems | No | 36.9 | 9.5 | 46.4 | 0.36 |

| Yes | 23.8 | 29.8 | 53.6 | ||

| T | 60.7 | 39.3 | 100 | ||

| Support network | No | 11 | 31.7 | 42.7 | 0.001 ** |

| Yes | 8.5 | 48.8 | 57.3 | ||

| T | 19.5 | 80.5 | 100 | ||

| Support people | No | 1.2 | 25.6 | 26.8 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 4.9 | 68.3 | 73.2 | ||

| T | 6.1 | 93.9 | 100 | ||

| Anxiety (Goldberg) | No | 52.4 | 4.8 | 57.2 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 36.9 | 6 | 42.9 | ||

| T | 89.3 | 10.8 | 100 | ||

| Depression (Goldberg) | No | 53.6 | 2.4 | 56 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 36.9 | 7.1 | 44 | ||

| T | 90.5 | 9.5 | 100 | ||

| Low perceived social support (Duke) | No | 67.9 | 0 | 67.9 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 30.9 | 1.2 | 32.1 | ||

| T | 98.8 | 1.2 | 100 | ||

| Unwanted loneliness (UCLA mod/sev) | No | 53.8 | 2.5 | 56.3 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 31.3 | 12.5 | 43.8 | ||

| T | 85 | 15 | 100 | ||

| % After | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % Before | No | Yes | T | p * |

| Have you felt extremely excited, nervous, or tense? | No | 34.9 | 12.0 | 46.9 | 0.001 ** |

| Yes | 37.3 | 15.7 | 53 | ||

| T | 72.2 | 27.7 | 100 | ||

| Have you been extremely worried about something? | No | 36.1 | 10.8 | 46.9 | 0.002 ** |

| Yes | 36.1 | 18.1 | 54.2 | ||

| T | 72.2 | 28.9 | 100 | ||

| Have you felt extremely irritable? | No | 65.1 | 3.6 | 68.7 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 26.5 | 4.8 | 31.3 | ||

| T | 91.6 | 8.4 | 100 | ||

| Have you had difficulties relaxing? | No | 57.8 | 6.0 | 63.8 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 31.3 | 4.8 | 36.1 | ||

| T | 89.2 | 10.8 | 100 | ||

| Have you felt you had little energy? | No | 39.8 | 10.8 | 50.6 | 0.003 ** |

| Yes | 33.7 | 15.7 | 49.4 | ||

| T | 73.5 | 26.5 | 100 | ||

| Have you lost interest in things? | No | 63.9 | 3.6 | 67.5 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 27.7 | 4.8 | 32.5 | ||

| T | 91.6 | 8.4 | 100 | ||

| Have you lost self-confidence? | No | 79.5 | 1.2 | 80.7 | 0.002 ** |

| Yes | 15.7 | 3.6 | 19.3 | ||

| T | 95.2 | 4.8 | 100 | ||

| Have you felt despair, hopelessness? | No | 71.1 | 1.2 | 72.3 | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 26.5 | 1.2 | 27.7 | ||

| T | 97.6 | 2.4 | 100 | ||

| % After | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % Before | No | Yes | T | p * |

| I receive visits from my friends and relatives. | NO | 22.9% | 41.0% | 63.9% | <0.001 ** |

| YES | 8.4% | 27.7% | 36.1% | ||

| T | 31.3% | 68.7% | 100.0% | ||

| I have help with issues related to my house. | No | 13.3% | 47.0% | 60.2% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 6.0% | 33.7% | 39.8% | ||

| T | 19.3% | 80.7% | 100.0% | ||

| I receive compliments and acknowledgments when I do my job well. | No | 6.0% | 47.0% | 53.0% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 3.6% | 43.4% | 47.0% | ||

| T | 9.6% | 90.4% | 100.0% | ||

| I receive love and affection. | No | 7.2% | 22.9% | 30.1% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 2.4% | 67.5% | 69.9% | ||

| T | 9.6% | 90.4% | 100.0% | ||

| I can talk to someone about my problems at work or at home. | No | 2.4% | 33.7% | 36.1% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 6.0% | 57.8% | 63.9% | ||

| T | 8.4% | 91.6% | 100.0% | ||

| I can talk to someone about my personal and family problems. | No | 3.6% | 37.3% | 41.0% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 9.6% | 49.4% | 59.0% | ||

| T | 13.3% | 86.7% | 100.0% | ||

| I can talk to someone about my personal and economic problems. | No | 4.8% | 39.8% | 44.6% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 7.2% | 48.2% | 55.4% | ||

| T | 12.0% | 88.0% | 100.0% | ||

| I receive invitations to entertain myself and go out with other people. | No | 8.4% | 39.8% | 48.2% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 8.4% | 43.4% | 51.8% | ||

| T | 16.9% | 83.1% | 100.0% | ||

| I receive useful advice when there is some important event in my life. | No | 1.2% | 45.8% | 47.0% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 2.4% | 50.6% | 53.0% | ||

| T | 3.6% | 96.4% | 100.0% | ||

| I have help when I’m ill in bed. | No | 4.8% | 30.1% | 34.9% | <0.001 ** |

| Yes | 2.4% | 62.7% | 65.1% | ||

| T | 7.2% | 92.8% | 100.0% | ||

| % After | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % Before | O/F | R/N | T | p * |

| How often do you feel unhappy doing so many things by yourself? | O/F | 9.6% | 27.7% | 37.3% | 0.002 ** |

| R/N | 7.2% | 55.4% | 62.7% | ||

| T | 16.9% | 83.1% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel that you have no one to talk to? | O/F | 6.0% | 30.1% | 36.1% | <0.001 ** |

| R/N | 2.4% | 61.4% | 63.9% | ||

| T | 8.4% | 91.6% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel that you can’t bear feeling alone? | O/F | 6.0% | 19.3% | 25.3% | <0.001 ** |

| R/N | 2.4% | 72.3% | 74.7% | ||

| T | 8.4% | 91.6% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel that nobody understands you? | O/F | 1.2% | 25.3% | 26.5% | <0.001 ** |

| R/N | 2.4% | 71.1% | 73.5% | ||

| T | 3.6% | 96.4% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you find yourself waiting for someone to call you or write to you? | O/F | 3.6% | 24.1% | 27.7% | <0.001 ** |

| R/N | 3.6% | 68.7% | 72.3% | ||

| T | 7.2% | 92.8% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel completely alone? | O/F | 7.2% | 22.9% | 30.1% | <0.001 ** |

| R/N | 3.6% | 66.3% | 69.9% | ||

| T | 10.8% | 89.2% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel incapable of reaching those around you and communicating with them? | O/F | 6.0% | 22.9% | 28.9% | <0.001 ** |

| R/N | 0% | 71.1% | 71.1% | ||

| T | 6.0% | 94.0% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel thirsty for company? | O/F | 8.4% | 21.7% | 30.1% | 0.023 ** |

| R/N | 7.2% | 62.7% | 69.9% | ||

| T | 15.7% | 84.3% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel that you find it difficult to make friends? | O/F | 8.4% | 28.9% | 37.3% | <0.001 ** |

| N | 3.6% | 59.0% | 62.7% | ||

| T | 12.0% | 88.0% | 100.0% | ||

| How often do you feel silenced and excluded by other people? | O/F | 1.2% | 19.3% | 20.5% | 0.093 |

| R/N | 8.4% | 71.1% | 79.5% | ||

| T | 9.6% | 90.4% | 100.0% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Francisco-Sánchez, A.; Martínez-León, S.; García-Pérez, A.; Báez-Hernández, J.A.; Rodríguez-Álvaro, M.; García-Hernández, A.M. Impact of a Multidimensional Community-Based Intervention on the Feeling of Unwanted Loneliness and Its Consequences: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121465

Francisco-Sánchez A, Martínez-León S, García-Pérez A, Báez-Hernández JA, Rodríguez-Álvaro M, García-Hernández AM. Impact of a Multidimensional Community-Based Intervention on the Feeling of Unwanted Loneliness and Its Consequences: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121465

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrancisco-Sánchez, Alba, Sofía Martínez-León, Alejandro García-Pérez, Juan Andrés Báez-Hernández, Martín Rodríguez-Álvaro, and Alfonso Miguel García-Hernández. 2025. "Impact of a Multidimensional Community-Based Intervention on the Feeling of Unwanted Loneliness and Its Consequences: A Quasi-Experimental Study" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121465

APA StyleFrancisco-Sánchez, A., Martínez-León, S., García-Pérez, A., Báez-Hernández, J. A., Rodríguez-Álvaro, M., & García-Hernández, A. M. (2025). Impact of a Multidimensional Community-Based Intervention on the Feeling of Unwanted Loneliness and Its Consequences: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare, 13(12), 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121465