It Takes a Village: Unpacking Contextual Factors Influencing Caregiving in Urban Poor Neighbourhoods of Bangalore, South India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting, Sampling, and Participants

- Participants agreed to participate and provided written informed consent.

- Participants could engage in discussions in the local languages (Kannada or Hindi).

2.2. Tool Development and Data Collection

An example question: “There are many things we do with our children that are influenced by the families we belong to, or the places we grow up in or even our religion—What influences the way you care for your child.”

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Reflexivity

3. Findings

3.1. Participants’ Profile (Table 1)

| Caregiver Type and ID | Age (Years) | Education | Occupation | Marital Status | HH Members | Monthly HH Income (INR) | Child Age (Years) | Child Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother_1 | 28 | High school | Semiskilled | Widow | 3 | 4500 | 6 | Male |

| Mother_2 | 34 | Primary school | Homemaker | Married | 7 | NA | 5 | Female |

| Mother_3 | 27 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 4 | 27,000 | 5 | Male |

| Mother_4 | 27 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 7 | 20,000 | 4 | Female |

| Mother_5 | 23 | High school | Unemployed | Separated | 6 | 10,000 | 5 | Male |

| Mother_6 | 34 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 5 | 15,000 | 5 | Male |

| Mother_7 | 27 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 5 | 20,000 | 5 | Female |

| Mother_8 | 32 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 5 | NA | 6 | Female |

| Mother_9 | 26 | High school | Semiskilled | Separated | 4 | 10,000 | 6 | Female |

| Mother_10 | 26 | Graduate | Professional | Married | 4 | 30,000 | 6 | Male |

| Mother_11 | 31 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 4 | 40,000 | 6 | Male |

| Mother_12 | 38 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 5 | 30,000 | 4 | Female |

| Mother_13 | 34 | High school | Semiskilled | Married | 9 | 20,000 | 4 | Female |

| Mother_14 | 30 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 5 | 15,000 | 4 | Female |

| Mother_15 | 29 | High school | Professional | Separated | 3 | NA | 4 | Male |

| Mother_16 | 32 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 6 | 7000 | 4 | Female |

| Grandmother_1 | 53 | Primary school | Unemployed | Married | 10 | NA | 5 | Female |

| Grandmother_2 | 61 | Illiterate | Unemployed | Widow | 9 | NA | 5 | Male |

| Grandmother_3 | 50 | High school | Unemployed | Widow | 5 | 25,000 | 4 | Female |

| Grandmother_4 | 55 | Illiterate | Unemployed | Widow | 4 | 25,000 | 4 | Female |

| Grandmother_5 | 50 | High school | Semiskilled | Married | 3 | NA | 5 | Male |

| Grandmother_6 | 50 | High school | Homemaker | Married | 6 | 50,000 | 5 | Female |

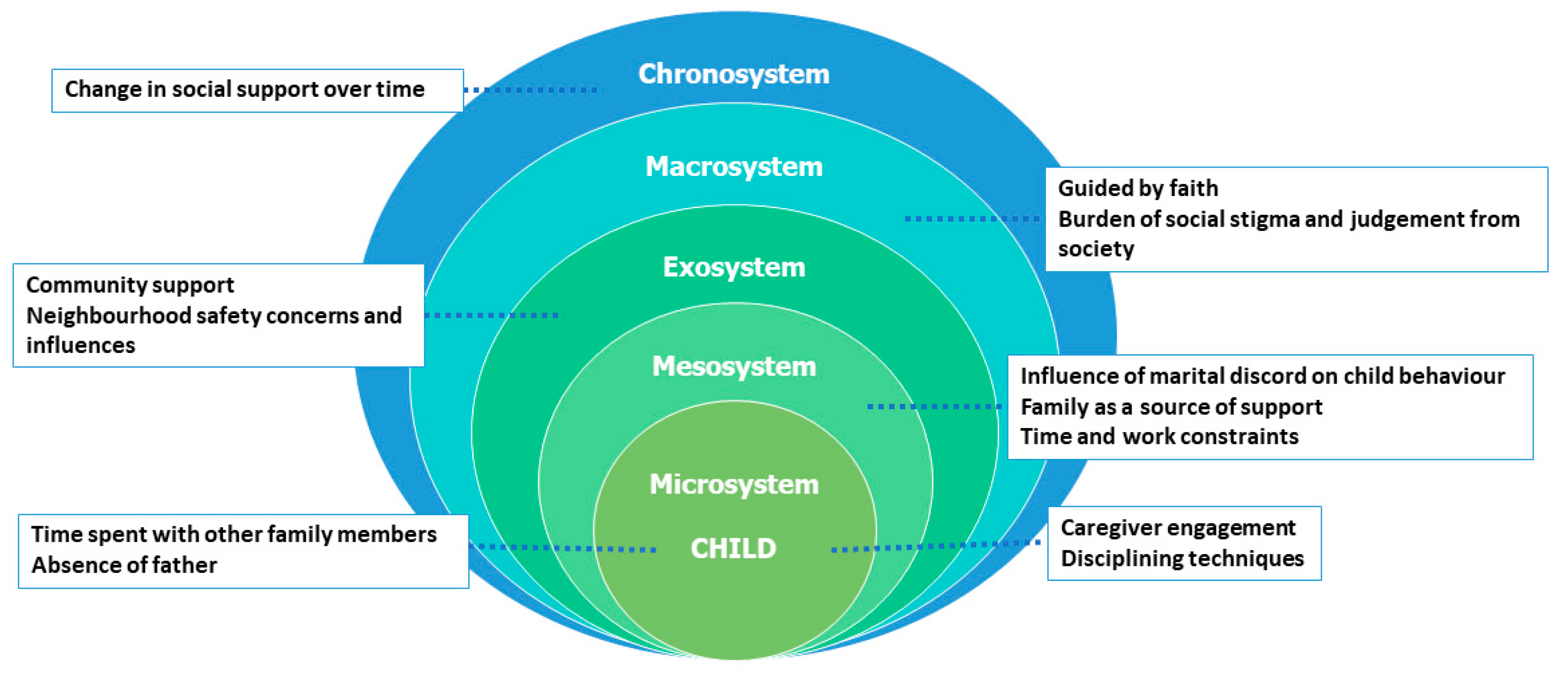

3.2. Themes Organized Using Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

3.2.1. Microsystem (Child’s Immediate Family and Home Environment)

Caregiver Engagement

“She likes talking, playing, and everything. Talking is her favourite; she loves to chat, and it’s really nice. I really enjoy it. The way she imitates her teacher and pretends to teach us.”(Mother_4, 4-year-old daughter)

“Whatever she learns in school, she tries to teach me. That makes me very happy. She holds the slate and teaches me letters.”(Mother_8, 6-year-old daughter)

“So, whenever I am washing utensils or doing chores, she comes and sits with me and sometimes even helps me with small tasks.”(Mother_2, 5-year-old daughter)

“He likes being with me, roaming around with me. He follows me everywhere and loves having snacks.”(Mother_3, 5-year-old son)

“If I am doing any work, he comes near me and asks if he can help. If I have time, I will allow him, but if not, I ask him to go.”(Mother_11, 6-year-old son)

Disciplining Techniques

“Both of them keep fighting. He says she hit him, and she says he hit her. It gets irritating for us. So we have to console both of them. He doesn’t understand because he’s the youngest, so I teach her to adjust and be patient with him.”(Mother_10 of 6-year-old son)

“She loves me a lot and always obeys my orders. If she doesn’t listen to us, I just show her the stick, and then she sits quietly.”(Mother_7, 5-year-old daughter)

One mother mentioned how she deals with her child not listening to her. She said, “I tell her she has to do it (homework), or I will have to tell her father. My husband doesn’t shout. I just tell her that she shouldn’t make her father angry and that she should do her homework.”(Mother_8, 6-year-old daughter)

“Sometimes he is afraid of me. I work in a boarding school, and I took him there to show him how other children behave. I explained how they follow the line, and I tell him that if he does not behave, I’ll put him in the hostel.”(Mother_10, 6-year-old son)

One mother shared, “Mostly he fights a lot with his brothers. So I beat him (laughing). That’s mostly the reason why I beat him.”(Mother_11, 6-year-old son)

“When I say no to certain things, she will not stay quiet. She starts crying, and that makes me angry. When I am stressed, I sometimes beat her to calm her down, and then I explain what she should not ask for.”(Mother_13, 4-year-old daughter)

“She does not have a father, and her mother is at work, so it’s not right to get angry with her. If we get angry, she becomes even angrier. She is very quick to anger—if we scold her, she runs to bed, lies down, and cries like an adult woman. That’s why we try to avoid scolding her.”(Grandmother_4, 4-year old granddaughter)

“We do not punish her physically. I only scold her sometimes, but no one else does. If she becomes very angry, she might shout at us. If her mother scolds her, she does not talk to her and complains to her grandfather.”(Grandmother_1, 5-year old granddaughter)

Time Spent with Other Family Members

For instance, one caregiver stated, “I am mostly busy with household chores, so she is usually engaged with my mother-in-law. She plays with her sister or with my mother-in-law. She loves her grandmother a lot, and her grandmother loves her a lot too. After waking up, she calls out, “Dadi, Dadi, Dadi.””(Mother_2, 5-year-old daughter)

Another mother described the close bond of her child and cousin, “She has an elder sister (cousin) named Madhu, whom she loves even more than me. As soon as she wakes up, she keeps chanting, “Madhu akka, Madhu akka.” If she can’t find her, she comes to me asking for Madhu akka. She makes sure she sees her, then goes to her asking for her toothbrush. She is the one who helps her bathe and brush her teeth.”(Mother_16, 5-year-old daughter)

“She plays more often with her grandfather. She fights very often with her grandmother. They do not get well along with each other since she disciplines her more. Her grandfather pampers her and she enjoys spending time with him. She also plays with her elder sister or aunt at home.”(Mother_4, 4-year-old daughter)

In one instance, another mother explained, “Sometimes if my children are not well, I take them to my parents’ house and go to work. My mother nurtures them back to health. They will also help in taking them to the doctor and look after them. My father also helps when my children at his house.”(Mother_3, 5-year-old son)

Absence of Father

“I want to send her to a dance class, but that is not possible, there is no one to pick and drop her and also to maintain the fees. I would like to put her in other classes but it is not possible in this situation. So being a single mother does affect things I want for her but am unable to do.”(Mother_9, 6-year-old daughter)

One grandmother expressed that “When she (child) sees other fathers, she feels sad; that is why we give her lots of love, we take her out often, give her all that we can afford, so she does not feel a void.”(Grandmother_4, 4-year old granddaughter)

Another mother added that, “I go to work, and my mother also works. We take advances and manage to buy books, uniforms, and everything else from our earnings.”(Mother_15, 4-year old son)

3.2.2. Mesosystem (Connections Between Microsystems)

Influence of Marital Discord on Child Behaviour

A mother explained, “First of all, parents should not fight in front of their children. If parents are like this, the children will go outside and learn these negative behaviours. To avoid this, there should be love and care in the family so the children can grow up in a better way.”(Mother_14, 4-year old daughter)

One mother said, that, “They (children) tend to imitate what they see. Even if we argue, we try to keep it out of their sight so they don’t realize we’re fighting.”(Mother_3, 5-year old son)

One mother with three children stressed that, “We do not even raise our voices in the house. We do not speak in a high pitch because children learn from what we do.”(Mother_12, 4-year old daughter)

“Most of the time, I am the one who gets angry, and my husband tries to control the situation. I am the one who speaks more, and he remains silent. We both have an understanding. He is a very mature person.”(Mother_6, 5-year old son)

Another mother said that, “Never fight or use abusive language in front of the kids; otherwise, it will stay in their minds. Even after they grow up, they will remember that their father did this or said that. That’s why I tell him not to say anything like that in front of the kids. Show only love in front of them, keep the tensions away from them, and let them focus on eating and studying. Don’t burden them with the problems we have. They should only know how to study and stand on their own feet, not about financial problems.”(Mother_8, 6-year old daughter)

A single mother separated from her abusive husband reiterated the negative influence of marital discord on child development. She said that, “I tried a lot to keep them from knowing too much. The elder one is aware of what happened, like how his father used to beat me, and he remembers everything. The younger one has not seen much of it, but the elder one does remember.”(Mother_5, 5-year old son)

Family as a Source of Support

“My mother-in-law, father-in-law, and my husband support me with taking care of my children. I think I am blessed to have this support, especially with three children.”(Mother_4, 4-year old daughter)

“I got married at a young age, which is why I could not complete my education. She (my sister) encouraged me to finish my studies. When I went outside to work, she looked after my children. At that time, I worked from morning to night, from 8 AM to 9 PM, so she took care of our children.”(Mother_10, 6-year old son)

One grandmother mentioned the support of her younger daughter as an alternate caregiver as well, “Her mother is not at home because she is working and cannot take leaves often. She works as a care sales executive, and her work demands here presence as it is primarily commission based. But since I do not keep well, especially after my recent heart issue, sometimes if I am not feeling well, my younger daughter steps up and takes care of her (grandchild). She is as loving to her as her own mother.”(Grandmother_4, 5-year old granddaughter)

Another participant described financial help from her sisters who lived close by, “My elder sister, all my sisters, are more like my mother. While I was in my tough times, while my husband and I had huge debts, they took such good care of my daughter, making her wear good clothes, taking her out. Though we were not able to go on any tours or picnic, they themselves took her sight-seeing, they got her back after enjoying it.”(Mother_16, 6-year old daughter)

A single mother explained how during her marriage her father supported her family and continues to do so after her separation from her husband. She said, “He (husband) did not earn money, so my father had to cover everything. Even when he did not pay the school fees, my father handled it. Now also, my family members help manage most of the responsibilities. I mainly look after my children.”(Mother_5, 5-year old son)

Another mother expressed lack of social support, “Everyone is there but not to help. Only me and my husband are involved in raising our children. We do not even rely on others’ advice. Our children belong to us. We gave birth to them, so we will raise them. We don’t get any help from anyone else, and we do not even want a single rupee from others.”(Mother_8, 6-year old daughter)

One mother shared her lack of support, including the financial woes she faces. She said, “Due to the low salary, my husband is facing many problems. He has several chit funds, loans, LIC payments, and fees to cover. He is managing all of this alone, and we do not have any support from our family. We help others, but we do not have anyone to help us.”(Mother_13, 4-year old daughter)

Time and Work Constraints

“Although most of my day is spent in household work or taking care of the baby, I always try to play with him for at least half an hour a day. I try my best since he likes it a lot. He and I play running races, hide and seek, clapping games, number learning, many more. Sometimes we will make up some games.”(Mother_6, 6-year old son)

“If she has a holiday, we go out sometimes. It’s not on a fixed schedule. Whenever we have time, we go out. Even if I have time on Sundays, her father might not. So, we go out whenever we can.”(Mother_2, 5-year old daughter)

“She makes up her own stories, or she will tell something from school. I like listening to her. I am busy in the day, so usually, we have our dinner while watching TV at night.”(Mother_9, 6-year old daughter)

“I can only spend time on weekends. I can’t during the week because of work pressure. By the time I come home, it’s already late, so I check to see if he has eaten or needs help with homework.”(Mother_15, 4-year old son)

“I would prefer financial help. It would be helpful if it came in the form of a job or some other means of earning. I need the money but cannot take on a job at the moment due to my child’s needs.”(Mother_5, 5-year old son)

“I would be interested in work that can be done from home, that would be really helpful. This way, I will not need to go outside and can spend more time with my children. If I have to go outside for work, I will not have enough time for them. So, having home-based work would be very beneficial. Currently I manage with the income from the auto rickshaw of my late husband, and some additional help by making plastic ornaments.”(Mother_1, 6-year old son)

3.2.3. Exosystem (Indirect Influences on Caregiving)

Community Support

“Sometimes, during holidays, I leave her with the neighbour’s children; they are older, so I leave her with them for half an hour or so, not more than that. I know them since many years so I can trust them with my children.”(Mother_12, 4-year old daughter)

“Despite being a slum area, neighbours do support each other and act like family. We have never faced discrimination from the Hindus; they stand by us, and we stand by them. They live happily, and its usually outsiders who cause trouble, not the neighbours.”(Mother_8, 6-year old daughter)

A single mother who is the primary breadwinner in her household mentioned that, “I don’t have any financial support as such; whatever I earn I use it, but I have support from my friends.”(Mother_15, 4-year old son)

Another widow mentioned that, “Although I have good relationships with people in our building, I rely on Allah and adjust according to what comes my way. If there is any shortage, my mother or brother help me out.”(Mother_1, 6-year old son)

Neighbourhood Safety Concerns and Influences

“No, we don’t allow her to play alone outside. She plays at home most of the times. Even though she has a cycle, she rides it only at home. Occasionally, in the evening, my mother takes her to the garden nearby.”(Mother_14, 4-year old daughter)

“I never leave my child anywhere. These days, things are getting worse for our daughters, so I have taught her about bad touch and how to avoid such situations. I tell her, “This is not school, so you should not go anywhere without telling us. If someone touches you inappropriately, inform me, your father, or my brother.””(Mother_13, 4-year old daughter)

“We do not let her go out much, because some people come here and engage in drug use and other addictions. Even after complaints, they continue to come, especially in this lane. The place we lived before, there was nothing like this. The situation worsened with the construction, which created more space for such activities. They even carry harmful objects, so we do not let our child go outside.”(Grandmother_6, 5-year-old granddaughter)

“Actually, I don’t trust the area much. Nowadays, we cannot even trust our extended family, so it is difficult to trust someone from the area. We usually manage ourselves or rely on my mother-in-law. It becomes difficult trying to manage all by myself, but thankfully sometimes I do have my mother-in-law who can look at the children. Although it is rare, it is valuable for me. Otherwise, it is not safe here, I feel.”(Mother_2, 5-year old daughter)

One caregiver stated that, “Children are affected by what happens at home and in their surroundings. For example, if there are bad influences or inappropriate behaviour in the area, it can impact them. If children hear bad language or see negative behaviour repeatedly, they might start mimicking it.”(Mother_6, 6-year old son)

One parent moved their child to another “safe” neighbourhood in order to protect them from negative environmental influences. She said, “There is indeed a drug issue in our area. My husband and I struggled to protect our children. We even had fights because of it, which affected our son. Because of this, I sent him (elder son) to my mother’s house.”(Mother_10, 6-year old son)

A grandmother reiterated her perceptions about the necessity to protect children from negative social environments with inappropriate behaviours; she said that, “If neighbouring children are using bad language or misbehaving, it can really affect children. That is why we do not let our children go out much.”(Grandmother_3, 4-year old daughter)

One grandmother considered children from government schools (usually from lower socio-economic backgrounds) a negative influence on other children. She said that, “We do not let them (children) go downstairs because even today, children from government schools often engage in mischief. If they use bad language or behave badly, our children might pick up those habits.”(Grandmother_2, 5-year old grandson)

3.2.4. Macrosystem (Cultural and Societal Influences)

Guided by Faith

A recently widowed mother explained, “One thing about our locality is that the Madrasa is nearby. I truly believe that it will help my children to become a good person in life. That is something that is very important to me. Not having a father but having this guidance is important. That is why I feel happy that we live close by to the mosque. We can tackle any problem if we live by understanding. We should not complain rather we should be grateful for the things—whether we are eating biryani one day and dal chawal (rice and lentil is considered frugal) the other day. Allah is there to give us. He will handle everything.”(Mother_1, 6-year old son)

Another mother explained about how rituals are important as a part of growing-up, she said, “Rituals are important for children to learn. Even during Pooja (prayers), we teach them, and they come close to watch and listen. If they learn at a young age, they will understand the importance of God. My husband and I feel this is very important for them.”(Mother_13, 4-year old daughter)

“We need to give them good values and morals, protect them from negativity, and all of this is taught very well in the Madrasa.”(Mother_3, 5-year old son)

“There are no friends here because we do not let him go downstairs. No child is allowed to go, not even the oldest. Otherwise, they might learn some bad things or pick up bad language. So, I make them read books, and then they spend time at the Madrasa.”(Mother_6, 5-year old son)

She proudly stated, “We (she and her husband) teach him how to pray Namaz, and he prays very beautifully, so well that the whole area can hear him.”(Grandmother_5, 5-year old grandson)

Burden of Social Stigma and Judgement from Society

“People say things like “she left her husband” or “her husband left her,” and it affects how they view me. They say many things, so I try not to go out much. Staying at home makes me feel peaceful and keeps me away from all that negativity.”(Mother_5, 5-year old son)

Another mother said, “I often feel that people might say hurtful things about me being a single mother or make false accusations if I talk to certain people. Some have also said unkind things, and it does hurt, but I can only turn to Allah for support.”(Mother_1, 6-year old son)

3.2.5. Chronosystem (Changes over Time)

Change in Social Support over Time

One emotional comment was, “I did not have any support here. I still do not have someone I can trust with my children. After my pregnancy, I came to Bangalore. I was in depression because of the lack of support. In my hometown, there were many people around me, but it is not the same here. I fell into depression because of that, but I learned everything by myself. Now I am managing with my children, but it gets challenging.”(Mother_11, 6-year old son)

Another mother expressed that her brother was a support to her earlier, but things changed now, “Earlier, when my child was born, I used to ask for help, as both my parents were alive. So I used to ask anything from my elder brother and he would help me, but now he is engaged in his own family, so I cannot ask him. Sometimes, I ask my mother, but it is not the same, she cannot help always.”(Mother_14, 4-year old daughter)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Policy Recommendations

- (a)

- Developing parenting programmes that promote effective practices and support maternal well-beingThere is an urgent need for parenting education programmes that are culturally sensitive and contextually relevant. Interventions that offer strategies for non-punitive discipline, effective communication, and stress management through peer support can empower caregivers to transition away from stigmatizing and authoritarian practices. Several participants noted that physical punishment left the mother feeling guilty afterwards, indicating a clear desire for gentler strategies. Our policy recommendation for non-punitive discipline thus arises directly from caregivers’ expressed need for alternatives and the emotional toll they reported. These programmes should also include dedicated components to challenge the stigma around single parenthood, such as peer support groups, community-based dialogues, and the positive role-modelling of diverse family structures. The importance of maternal well-being integrated in these programmes can provide a support system for mothers as a safe space to reflect, share, and connect, without stigma or judgement, especially for women with little to no social support and single mothers that face additional stressors.

- (b)

- Strengthening community and public support systems for caregiversThe mesosystem and chronosystem findings highlight the critical role of sustained social support. The presence of safe public services, such as crèches, or community-based interventions, such as local support groups, neighbourhood programmes, and community centres, can help build and maintain social networks. Such initiatives can help mitigate emotional isolation and perhaps provide avenues for improving parenting practices. Further, expanding and improving public crèche facilities, such as those under the National Crèche Scheme and Anganwadi centres, can provide safe and nurturing environments for children while supporting working parents in low-resource urban settings. These services not only benefit children by supporting early development and school readiness but also enable mothers and caregivers to engage in paid work, thereby contributing to households’ income, autonomy, and economic mobility. However, the current quality of these services remains inadequate, with many centres under-resourced, poorly staffed, and operating for limited hours that do not provide help to working mothers’ schedules. Hence, strengthening these services could be a powerful step towards supporting more women in the workforce, thus empowering them and also improving child outcomes.

- (c)

- Improving infrastructure and safety with special attention to poor neighbourhoodsGiven the constraints identified in the exosystem, urban planning must prioritize the creation of safe, accessible public spaces such as parks and well-lit streets, with special attention to poor neighbourhoods. Investments in improving neighbourhood safety can reduce environmental stressors that negatively impact caregiving practices.

- (d)

- Emphasizing longitudinal researchThe temporal dimension captured by the chronosystem underscores the necessity of longitudinal studies that can track changes in caregiving practices and support networks over time. Such research is critical for understanding the long-term effects of stressors and for designing interventions that adapt to the evolving needs of caregivers and their children in the urban poor neighbourhoods of Bangalore.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landry, S.H.; Smith, K.E.; Swank, P.R.; Zucker, T.; Crawford, A.D.; Solari, E.F. The effects of a responsive parenting intervention on parent-child interactions during shared book reading. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 48, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, M.A.; Yousafzai, A.K. The development and reliability of an observational tool for assessing mother–child interactions in field studies-experience from Pakistan. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development: A Framework for Helping Children Survive and Thrive to Transform Health and Human Potential; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Black, M.M.; Richter, L.M. Risk of poor development in young children in low-income and middle-income countries: An estimation and analysis at the global, regional, and country level. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e916–e922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, M.M.; Walker, S.P.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Andersen, C.T.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Lu, C.; McCoy, D.C.; Fink, G.; Shawar, Y.R.; Shiffman, J.; et al. Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course. Lancet 2017, 389, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trude, A.C.B.; Richter, L.M.; Behrman, J.R.; Stein, A.D.; Menezes, A.M.B.; Black, M.M. Effects of responsive caregiving and learning opportunities during pre-school ages on the association of early adversities and adolescent human capital: An analysis of birth cohorts in two middle-income countries. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neppl, T.K.; Jeon, S.; Diggs, O.; Donnellan, M.B. Positive parenting, effortful control, and developmental outcomes across early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahhalé, I.; Barry, K.R.; Hanson, J.L. Positive parenting moderates associations between childhood stress and corticolimbic structure. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgad145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoy, D.C.; Seiden, J.; Cuartas, J.; Pisani, L.; Waldman, M. Estimates of a multidimensional index of nurturing care in the next 1000 days of life for children in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Children’s and Adolescent’s Health. Country Profiles for Early Childhood Development; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Systems Theory; JAI: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1989; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, P.; An, I.S. Review of studies applying Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory in international and intercultural education research. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1233925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, P.L.; Black, M.M.; Behrman, J.R.; De Mello, M.C.; Gertler, P.J.; Kapiriri, L.; Martorell, R.; Young, M.E. Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet 2007, 369, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Review, W.P. Bangalore Population. 2025. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/india/bangalore (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Board KSD. Annual Report 2022–23. 2023. Available online: https://ksdb.karnataka.gov.in/storage/pdf-files/AnnualReport2022-23-Final.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Lobo, E.; Deepa, R.; Mandal, S.; Menon, J.; Roy, A.; Dixit, S.; Gupta, R.; Swaminathan, S.; Thankachan, P.; Bhavnani, S.; et al. Protocol of the Nutritional, Psychosocial, and Environmental Determinants of Neurodevelopment and Child Mental Health (COINCIDE) study. Welcome Open Res. 2024, 9, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, E.; Ana, Y.; Deepa, R.; Shriyan, P.; Sindhu, N.D.; Karthik, M.; Kinra, S.; Murthy, G.V.S.; Babu, G.R. Cohort profile: Maternal antecedents of adiposity and studying the transgenerational role of hyperglycaemia and insulin (MAASTHI). BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, G.R.; Murthy, G.V.S.; Deepa, R.; Yamuna; Prafulla; Kumar, H.K.; Karthik, M.; Deshpande, K.; Benjamin Neelon, S.E.; Prabhakaran, D.; et al. Maternal antecedents of adiposity and studying the transgenerational role of hyperglycemia and insulin (MAASTHI): A prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, Z.; Christopher, C.; Naidoo, D. Caregivers’ perception of their role in early childhood development and stimulation programmes in the early childhood development phase within a sub-Saharan African context: An integrative review. S. Afr. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 51, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Dodge, K.A.; Bates, J.E.; Pettit, G.S. Ethnic differences in the link between physical discipline and later adolescent externalizing behaviors. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Lansford, J.E.; Chang, L.; Zelli, A.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Dodge, K.A. Parent Discipline Practices in an International Sample: Associations with Child Behaviors and Moderation by Perceived Normativeness. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 487–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladstone, M.; Phuka, J.; Mirdamadi, S.; Chidzalo, K.; Chitimbe, F.; Koenraads, M.; Maleta, K. The care, stimulation and nutrition of children from 0–2 in Malawi—Perspectives from caregivers; “Who’s holding the baby?”. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahun, M.N.; Bliznashka, L.; Karuskina-Drivdale, S.; Regina, G.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Jeong, J. A qualitative study of maternal and paternal parenting knowledge and practices in rural Mozambique. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, S.a.M. Childcare practices in three Asian countries. Int. J. Early Child. 2005, 37, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harknett, K.S.; Hartnett, C.S. Who Lacks Support and Why? An Examination of Mothers’ Personal Safety Nets. J. Marriage Fam. 2011, 73, 861–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalomo, E.N.; Besthorn, F.H. Caregiving in Sub-Saharan Africa and older, female caregivers in the era of HIV/AIDS: A Namibian perspective. GrandFamilies Contemp. J. Res. Pract. Policy 2018, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick, E.M.; Doom, J.R. Associations between maternal perceptions of social support and adolescent weight status: A longitudinal analysis. SSM Popul. Health 2024, 25, 101647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanishi, Y.; Ikehara, S.; Aochi, Y.; Sobue, T.; Iso, H. The association between maternal social support levels during pregnancy and child development at three years of age: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2024, 29, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdepuro, A.; Räikkönen, K.; Pham, H.; Thompson-Felix, T.; Eid, R.S.; O’Connor, T.G.; Glover, V.; Lahti, J.; Heinonen, K.; Wolford, E. Maternal social support during and after pregnancy and child cognitive ability: Examining timing effects in two cohorts. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuijers, M.; Greenwood, C.J.; McIntosh, J.E.; Youssef, G.; Letcher, P.; Macdonald, J.A.; Spry, E.; Le Bas, G.; Teague, S.; Biden, E.; et al. Maternal perinatal social support and infant social-emotional problems and competencies: A longitudinal cross-cohort replication study. Arch Womens Ment. Health 2024, 27, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooklin, A.R.; Westrupp, E.; Strazdins, L.; Giallo, R.; Martin, A.; Nicholson, J.M. Mothers’ work-family conflict and enrichment: Associations with parenting quality and couple relationship. Child Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, B.E.; Gortmaker, S.L.; Bull, F.C.; Buka, S.L. Unsafe to play? Neighborhood disorder and lack of safety predict reduced physical activity among urban children and adolescents. Am. J. Health Promot. 2004, 18, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, R.J. Family, religious attendance, and trajectories of psychological well-being among youth. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, C.J.; Janicki, D.L. Parent-child communication about religion: Survey and diary data on unilateral transmission and bi-directional reciprocity styles. Rev. Relig. Res. 2003, 44, 252–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamis, D.A.; Wilson, C.K.; Tarantino, N.; Lansford, J.E.; Kaslow, N.J. Neighborhood disorder, spiritual well-being, and parenting stress in African American women. J. Fam. Psychol. 2014, 28, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, M.; Kelly, G. Constructing the “good” mother: Pride and shame in lone mothers’ narratives of motherhood. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 42, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstam, V.; Karwin, S.; Curran, T.; Lyons, M.; Celen-Demirtas, S. Stigma and divorce: A relevant lens for emerging and young adult women? J. Divorce Remarriage 2016, 57, 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkauskas, N.V. Three-generation family households: Differences by family structure at birth. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomaguchi, K.; Milkie, M.A. Parenthood and well-being: A decade in review. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Framework Level | Theme | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Microsystem | Caregiver engagement | “She likes talking, playing, and everything. Talking is her favourite; she loves to chat, and it’s really nice. I really enjoy it. The way she imitates her teacher and pretends to teach us.” (Mother_4, 4-year-old daughter) |

| Disciplining techniques | “She loves me a lot and always obeys my orders. If she doesn’t listen to us, I just show her the stick, and then she sits quietly.” (Mother_7, 5-year-old daughter) | |

| Time spent with other family members | “I am mostly busy with household chores, so she is usually engaged with my mother-in-law. She plays with her sister or with my mother-in-law. She loves her grandmother a lot, and her grandmother loves her a lot too. After waking up, she calls out, “Dadi, Dadi, Dadi.”” (Mother_2, 5-year-old daughter) | |

| Absence of father | “When she (child) sees others fathers she feels sad that is why we give her lots of love, we take her out often, give her all that we can afford, so she does not feel a void.” (Grandmother_4, 4-year old granddaughter) | |

| Mesosystem | Influence of marital discord on child behaviour | “They (children) tend to imitate what they see. Even if we argue, we try to keep it out of their sight so they don’t realize we’re fighting.” (Mother_3, 5-year old son) |

| Family as a source of support | “He (husband) did not earn money, so my father had to cover everything. Even when he did not pay the school fees, my father handled it. Now also, my family members help manage most of the responsibilities. I mainly look after my children.” (Mother_5, 5-year old son) | |

| Time and work constraints | “She makes up her own stories, or she will tell something from school. I like listening to her. I am busy in the day, so usually, we have our dinner while watching TV at night.” (Mother_9, 6-year old daughter) | |

| Exosystem | Community support | “Sometimes, during holidays, I leave her with the neighbour’s children; they are older, so I leave her with them for half an hour or so, not more than that. I know them since many years so I can trust them with my children.” (Mother_12, 4-year old daughter) |

| Neighbourhood safety concerns and influences | “Children are affected by what happens at home and in their surroundings. For example, if there are bad influences or inappropriate behaviour in the area, it can impact them. If children hear bad language or see negative behaviour repeatedly, they might start mimicking it.” (Mother_6, 6-year old son) | |

| Macrosystem | Guided by faith | “Rituals are important for children to learn. Even during Pooja (prayers), we teach them, and they come close to watch and listen. If they learn at a young age, they will understand the importance of God. My husband and I feel this is very important for them.” (Mother_13, 4-year old daughter) |

| Burden of social stigma and judgement from society | “I often feel that people might say hurtful things about me being a single mother or make false accusations if I talk to certain people. Some have also said unkind things, and it does hurt, but I can only turn to Allah for support.” (Mother_1, 6-year old son) | |

| Chronosystem | Change in social support over time | “I did not have any support here. I still do not have someone I can trust with my children. After my pregnancy, I came to Bangalore. I was in depression because of the lack of support. In my hometown, there were many people around me, but it is not the same here. I fell into depression because of that, but I learned everything by myself. Now I am managing with my children, but it gets challenging.” (Mother_11, 6-year old son) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lobo, E.; Babu, G.R.; Mukherjee, D.; van Schayck, O.C.P.; Srinivas, P.N. It Takes a Village: Unpacking Contextual Factors Influencing Caregiving in Urban Poor Neighbourhoods of Bangalore, South India. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121459

Lobo E, Babu GR, Mukherjee D, van Schayck OCP, Srinivas PN. It Takes a Village: Unpacking Contextual Factors Influencing Caregiving in Urban Poor Neighbourhoods of Bangalore, South India. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121459

Chicago/Turabian StyleLobo, Eunice, Giridhara Rathnaiah Babu, Debarati Mukherjee, Onno C. P. van Schayck, and Prashanth Nuggehalli Srinivas. 2025. "It Takes a Village: Unpacking Contextual Factors Influencing Caregiving in Urban Poor Neighbourhoods of Bangalore, South India" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121459

APA StyleLobo, E., Babu, G. R., Mukherjee, D., van Schayck, O. C. P., & Srinivas, P. N. (2025). It Takes a Village: Unpacking Contextual Factors Influencing Caregiving in Urban Poor Neighbourhoods of Bangalore, South India. Healthcare, 13(12), 1459. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121459

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)