Empowering Men to Take Control of Their Own Health: Development and Validation of the Men’s Response to Colorectal Cancer Screening Scale (MR–CCSS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Scale Development

Item Generation Based on Qualitative Data

2.2. Pilot Study

2.2.1. Content Validity of the Newly Developed Scale

2.2.2. Construct Validity and Reliability

2.3. Sample

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

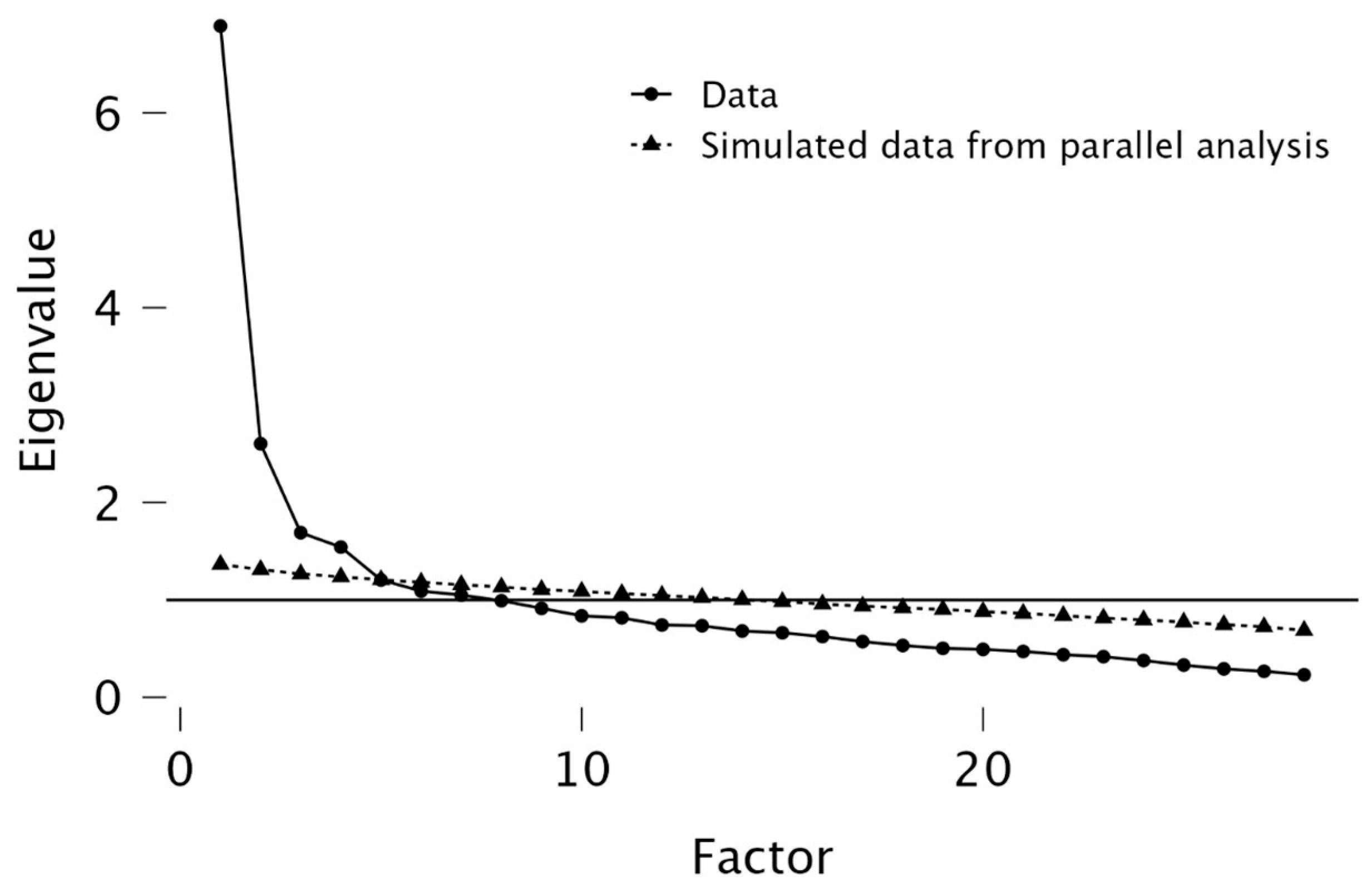

3.2. Construct Validity

3.3. Internal Consistency

3.4. Scoring of the Men’s Response to Colorectal Cancer Screening Scale (MR–CCSS)

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morgan, E.; Arnold, M.; Gini, A.; Lorenzoni, V.; Cabasag, C.J.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Murphy, N.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Colorectal Cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and Mortality Estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 2023, 72, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission European Commission Initiative on Colorectal Cancer, Cancer Screening, Diagnosis and Care. Available online: https://cancer-screening-and-care.jrc.ec.europa.eu/en/ecicc (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- SVIT It’s Time to Think About Yourself! Available online: https://www.program-svit.si/en/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Albers, B.; Auer, R.; Caci, L.; Nyantakyi, E.; Plys, E.; Podmore, C.; Riegel, F.; Selby, K.; Walder, J.; Clack, L. Implementing Organized Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs in Europe-Protocol for a Systematic Review of Determinants and Strategies. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Schrijvers, J.J.A.; Greuter, M.J.W.; Kats-Ugurlu, G.; Lu, W.; de Bock, G.H. Effectiveness of Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening on All-Cause and CRC-Specific Mortality Reduction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2023, 15, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, E.M.; Shim, H.; Zhang, Y.S.; Kim, J.K. Differences between Men and Women in Mortality and the Health Dimensions of the Morbidity Process. Clin. Chem. 2019, 65, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.R.; Peak, T.; Gast, J.; Arnell, M. Associations Between Masculine Norms and Health-Care Utilization in Highly Religious, Heterosexual Men. Am. J. Mens Health 2019, 13, 1557988319856739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.G. Changing Men’s Health: Leading the Future. World, J. Mens Health 2018, 36, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.; Ironmonger, L.; Steele, R.J.C.; Ormiston-Smith, N.; Crawford, C.; Seims, A. A Review of Sex-Related Differences in Colorectal Cancer Incidence, Screening Uptake, Routes to Diagnosis, Cancer Stage and Survival in the UK. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannenbaum, C. Gender-Based Analysis Using Existing Public Health Datasets. Can. J. Public Health Rev. Can. Sante Publique 2020, 111, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielke, J.; Batram-Zantvoort, S.; Razum, O.; Miani, C. Operationalising Masculinities in Theories and Practices of Gender-Transformative Health Interventions: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2023, 22, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, R.B.; Assefa, Y. Access to Health Services among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations in the Australian Universal Health Care System: Issues and Challenges. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, M.M.; Reidy, M.; Hegarty, J.; O’Mahony, M.; Murphy, M.; Von Wagner, C.; Drummond, F.J. Men’s Information-Seeking Behavior Regarding Cancer Risk and Screening: A Meta-Narrative Systematic Review. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, J.; Simoes, E.; Kranz, A.; Weinert, K.; Abele, H. The Importance of Gender-Sensitive Health Care in the Context of Pain, Emergency and Vaccination: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Flores, E.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Élez, E.; Redondo-Cerezo, E.; Safont, M.J.; Vera García, R. Gender and Sex Differences in Colorectal Cancer Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jašić, V.; Ličen, S.; Prosen, M. Factors determining men’s behavior regarding participation in screening programs for early detection of colorectal cancer: A qualitative analysis. Slov. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 57, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R.; Cairney, J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-176545-2. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The Content Validity Index: Are You Sure You Know What’s Being Reported? Critique and Recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2006, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M. ABC of Content Validation and Content Validity Index Calculation. Educ. Med. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum Sample Size Recommendations for Conducting Factor Analyses. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schisterman, E.F.; Faraggi, D.; Reiser, B.; Hu, J. Youden Index and the Optimal Threshold for Markers with Mass at Zero. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wools, A.; Dapper, E.A.; Leeuw, J.R.J. de Colorectal Cancer Screening Participation: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, G.; Aisenberg-Shafran, D.; Levi-Belz, Y. Adherence to Masculinity Norms and Depression Symptoms Among Israeli Men: The Moderating Role of Psychological Flexibility. Am. J. Mens Health 2024, 18, 15579883241253820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, A.; Eggenberger, L.; Grub, J.; Ogrodniczuk, J.S.; Seidler, Z.E.; Rice, S.M.; Kealy, D.; Oliffe, J.L.; Ehlert, U. Examining the Role of Traditional Masculinity and Depression in Men’s Risk for Contracting COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alodhialah, A.M.; Almutairi, A.A.; Almutairi, M. Assessing Barriers to Cancer Screening and Early Detection in Older Adults in Saudi Arabia: A Mixed-Methods Approach to Oncology Nursing Practice Implications. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 7872–7889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-Y.; Wei, C.-Y.; Wu, M.-H.; Hsieh, C.-M. Determinants of the Public Health Promotion Behavior: Evidence from Repurchasing Health Foods for Improving Gastrointestinal Tract Functions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 7604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.E.; Anisimowicz, Y.; Miedema, B.; Hogg, W.; Wodchis, W.P.; Aubrey-Bassler, K. The Influence of Gender and Other Patient Characteristics on Health Care-Seeking Behaviour: A QUALICOPC Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Mulenga, L. Health Consciousness: Theory, Measurement, and Evidence. In Handbook of Concepts in Health, Health Behavior and Environmental Health; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus, M.; Rodrigue, C.M.; Rahmani, S.; Balamou, C. Addressing Cancer Screening Inequities by Promoting Cancer Prevention Knowledge, Awareness, Self-Efficacy, and Screening Uptake Among Low-Income and Illiterate Immigrant Women in France. Int. J. Public Health 2021, 66, 1604055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borlu, A.; Şentürk, H.; Durmuş, H.; Öner, N.; Tan, E.; Köleniş, U.; Duman Erbakırcı, M.; Çetinkaya, F. Bridging Lifestyle and Screening for Cancer Prevention: A Comprehensive Analysis of Cancer-Related Lifestyle and Screening Attitudes in Adults. Medicina 2025, 61, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogonchi, M.; Mohammadzadeh, F.; Moshki, M. Investigating the Relationship between Health Locus of Control and Health Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Open Public Heal. Public Health 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, C.; McGuiness, C.; Duncan, A.; Turnbull, D. Masculinity and Men’s Participation in Colorectal Cancer Screening. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2015, 16, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg-Beckhoff, G.; Leppin, A.; Nielsen, J.B. Reasons for Participation and Non-Participation in Colorectal Cancer Screening. Public Health 2022, 205, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, C.; Adıgüzel, L.; Demirbağ, B.C. The Relationship between Men’s Health Literacy Levels and Their Health Beliefs and Attitudes towards Prostate Cancer Screening: A Case Study in a Rural Area. Support. Care Cancer Off. J. Multinatl. Assoc. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabel, P.; Larsen, M.B.; Edwards, A.; Kirkegaard, P.; Andersen, B. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Worries among Different Health Literacy Groups before Receiving First Invitation to Colorectal Cancer Screening: Cross-Sectional Study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 14, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavers, D.; Nelson, M.; Rostron, J.; Robb, K.A.; Brown, L.R.; Campbell, C.; Akram, A.R.; Dickie, G.; Mackean, M.; van Beek, E.J.R.; et al. Understanding Patient Barriers and Facilitators to Uptake of Lung Screening Using Low Dose Computed Tomography: A Mixed Methods Scoping Review of the Current Literature. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocco, K.; Masiero, M.; Carriero, M.C.; Pravettoni, G. The Role of Emotions in Cancer Patients’ Decision-Making. Ecancermedicalscience 2019, 13, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Employment status: | ||

| Employed | 183 | 63.3 |

| Self-employed | 34 | 11.8 |

| Retired | 70 | 24.2 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 0.7 |

| Level of education: | ||

| Primary education (ISCED 1/SOK II) | 20 | 6.9 |

| Lower vocational education (ISCED 2–3C/SOK III–IV) | 59 | 20.4 |

| Upper secondary education (ISCED 3A/SOK V) | 105 | 36.3 |

| Short-cycle higher education/professional diploma (SOK VI/1) | 42 | 14.5 |

| Bachelor’s degree (Bologna 1st cycle/SOK VI/2) | 32 | 11.1 |

| Master’s degree (Bologna 2nd cycle/SOK VII, VIII/1) | 36 | 12.5 |

| Doctoral degree (Bologna 3rd cycle/SOK VIII/2) | 7 | 2.4 |

| Participation in the Svit Programme (stool sample submitted) | ||

| Yes | 221 | 76.5 |

| No | 68 | 23.5 |

| Items | Factor Loadings | z-Value | p | I-CVI (R, C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | I hesitate to talk about digestive problems. | 0.820 | 23.47 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| I believe that it is inappropriate to talk about the bowel and the anus. | 0.783 | 14.74 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| I don’t talk to anyone about problems involving intimate parts of the body. | 0.688 | 20.46 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| I am afraid that people will think I am homosexual if I undergo a colonoscopy. | 0.682 | 14.04 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| I didn’t take part in the Svit programme because I didn’t understand the language. | 0.619 | 14.97 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| I think women have a higher risk of developing colorectal cancer. | 0.580 | 12.20 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| Colorectal cancer only affects people who sit too much. | 0.548 | 14.20 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| In our family, it is the woman who looks after the health of the family members. | 0.508 | 9.80 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| I think the Svit programme is unnecessary because I already know the signs of colorectal cancer. | 0.408 | 11.60 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| Factor 2 | I didn’t respond to the invitation to the Svit programme because I don’t think I have any health problems. | 0.892 | 24.24 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| I don’t have time to take part in screening programmes. | 0.878 | 24.00 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| It would be easier for me if my GP invited me to the Svit programme and the nurse explained everything to me. | 0.678 | 20.59 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| I didn’t fully understand the invitation to the Svit screening programme. | 0.528 | 15.80 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| I don’t take care of my own bowel movements; if necessary, the doctor sends me for a check-up. | 0.408 | 19.50 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| Factor 3 | I make sure I lead a healthy lifestyle. | 0.870 | 22.07 | <0.001 | 0.82 |

| I believe that my lifestyle is healthy. | 0.805 | 18.91 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| I make sure I am physically active for at least 30 min every day. | 0.649 | 15.80 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| Factor 4 | I know what screening programmes are. | 0.840 | 16.12 | <0.001 | 0.91 |

| I know what a colonoscopy is. | 0.647 | 10.80 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| I know the purpose of the Svit screening programme. | 0.527 | 18.72 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| I know the risk factors for developing colorectal cancer. | 0.513 | 11.45 | <0.001 | 0.91 | |

| Factor 5 | I am afraid that the test will reveal something that could lead to death. | 0.828 | 19.37 | <0.001 | 1.00 |

| I am afraid that cancer will be found if I take part in the Svit programme. | 0.787 | 16.38 | <0.001 | 1.00 | |

| Factors | Estimate | Std.Error | z-Value | p | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Stigma, embarrassment and shame ↔ Denial of the need for screening and excuses | 0.619 | 0.013 | 46.875 | <0.001 | 0.593 | 0.645 |

| Stigma, embarrassment and shame ↔ Healthy lifestyle and positive attitude towards health | 0.197 | 0.014 | 14.195 | <0.001 | 0.170 | 0.244 |

| Stigma, embarrassment and shame ↔ Understanding the screening programme | 0.380 | 0.013 | 30.252 | <0.001 | 0.356 | 0.405 |

| Stigma, embarrassment and shame ↔ Fear of diagnosis and disease | 0.440 | 0.014 | 30.577 | <0.001 | 0.412 | 0.468 |

| Denial of the need for screening and excuses ↔ Healthy lifestyle and positive attitude towards health | 0.172 | 0.015 | 11.498 | <0.001 | 0.143 | 0.201 |

| Denial of the need for screening and excuses ↔ Understanding of the screening programme | 0.455 | 0.013 | 34.931 | <0.001 | 0.420 | 0.480 |

| Denial of the need for screening and excuses ↔ Fear of diagnosis and disease | 0.454 | 0.014 | 31.337 | <0.001 | 0.425 | 0.482 |

| Healthy lifestyle and positive attitude towards health ↔ Understanding of the screening programme | 0.261 | 0.016 | 16.619 | <0.001 | 0.230 | 0.292 |

| Healthy lifestyle and positive attitude towards health ↔ Fear of diagnosis and disease | 0.215 | 0.019 | 11.385 | <0.001 | 0.178 | 0.251 |

| Understanding of the screening programme ↔ Fear of diagnosis and disease | 0.245 | 0.014 | 16.884 | <0.001 | 0.216 | 0.273 |

| Factors/Subscales | n | Mean | SD | Cronbach α | 95% Confidence Interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Stigma, embarrassment and shame | 9 | 1.51 | 0.485 | 0.782 | 1.47 | 1.54 | <0.001 |

| Denial of the need for screening and excuses | 5 | 1.57 | 0.710 | 0.828 | 1.52 | 1.62 | <0.001 |

| Healthy lifestyle and positive attitude towards health | 3 | 3.79 | 0.682 | 0.758 | 3.74 | 3.84 | <0.001 |

| Understanding the screening programme | 4 | 4.06 | 0.687 | 0.665 | 4.01 | 4.11 | <0.001 |

| Fear of diagnosis and disease | 2 | 1.88 | 1.042 | 0.833 | 1.80 | 1.95 | <0.001 |

| Men’s Response to Colorectal Cancer Screening Scale (MR–CCSS) | 23 | 2.29 | 0.348 | 0.863 | 2.27 | 2.32 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jašić, V.; Prosen, M.; Ličen, S. Empowering Men to Take Control of Their Own Health: Development and Validation of the Men’s Response to Colorectal Cancer Screening Scale (MR–CCSS). Healthcare 2025, 13, 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121433

Jašić V, Prosen M, Ličen S. Empowering Men to Take Control of Their Own Health: Development and Validation of the Men’s Response to Colorectal Cancer Screening Scale (MR–CCSS). Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121433

Chicago/Turabian StyleJašić, Vesna, Mirko Prosen, and Sabina Ličen. 2025. "Empowering Men to Take Control of Their Own Health: Development and Validation of the Men’s Response to Colorectal Cancer Screening Scale (MR–CCSS)" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121433

APA StyleJašić, V., Prosen, M., & Ličen, S. (2025). Empowering Men to Take Control of Their Own Health: Development and Validation of the Men’s Response to Colorectal Cancer Screening Scale (MR–CCSS). Healthcare, 13(12), 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121433