The Effectiveness of Group and Individual Training in Emotional Freedom Techniques for Patients in Remission from Melanoma: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To assess the effect of the instruction and practice of Clinical EFT on wellbeing, emotions, fear of cancer recurrence, and perceptions of recurrence in cutaneous melanoma survivors in remission, comparing changes over time between EFT and a control condition.

- To assess whether EFT instruction in a group setting, which has the potential to provide social support, makes this efficient mode of implementation non-inferior or even beneficial in comparison to personal instruction.

- To assess changes in SUD scores during EFT sessions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

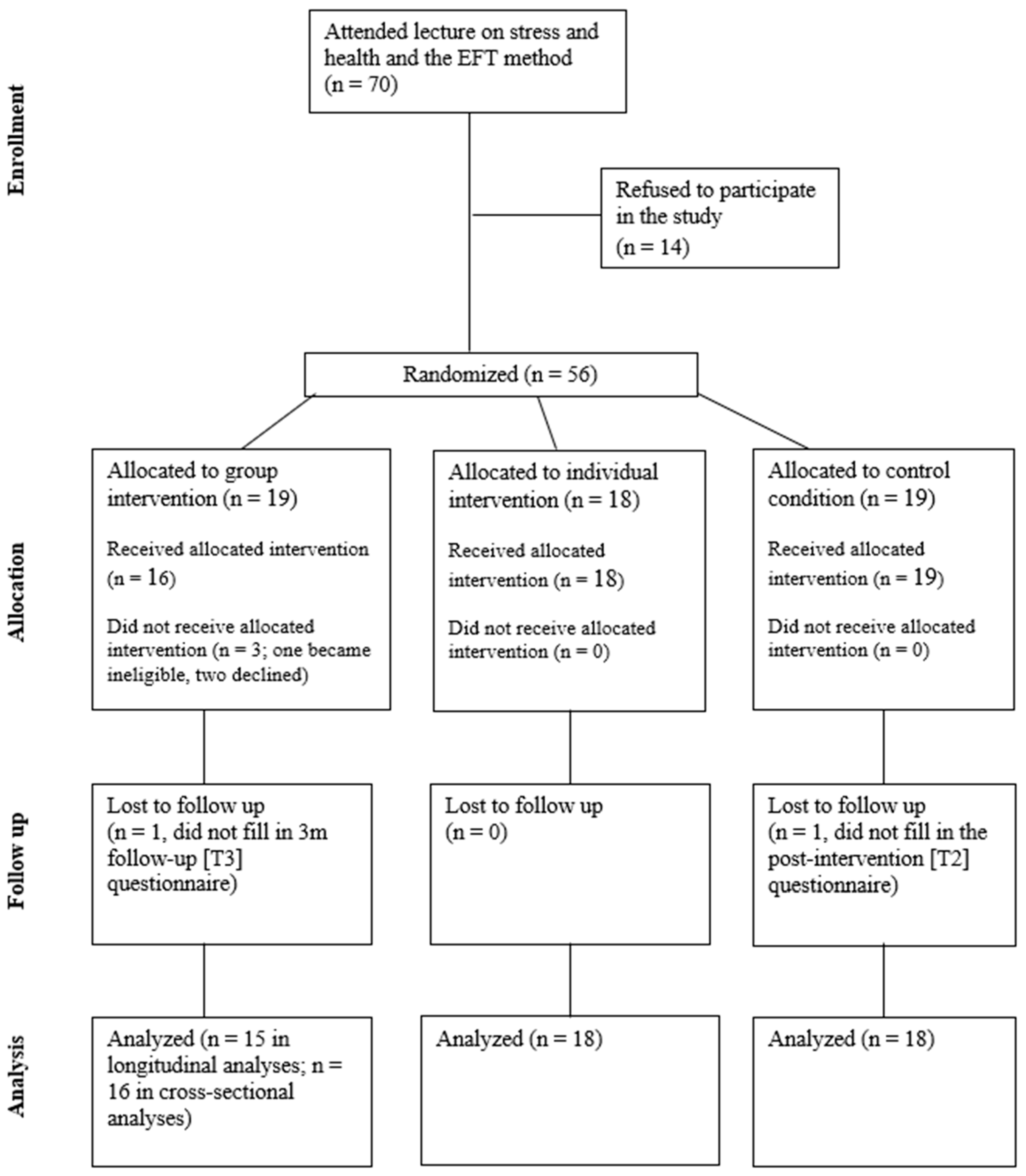

2.2. Sample

2.3. Recruitment and Procedure

2.4. EFT Instruction and Practice

2.5. EFT Protocol

2.6. Instruments

2.7. EFT Practice and Satisfaction

2.8. General Notes

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Health and Heath Behaviors at Baseline

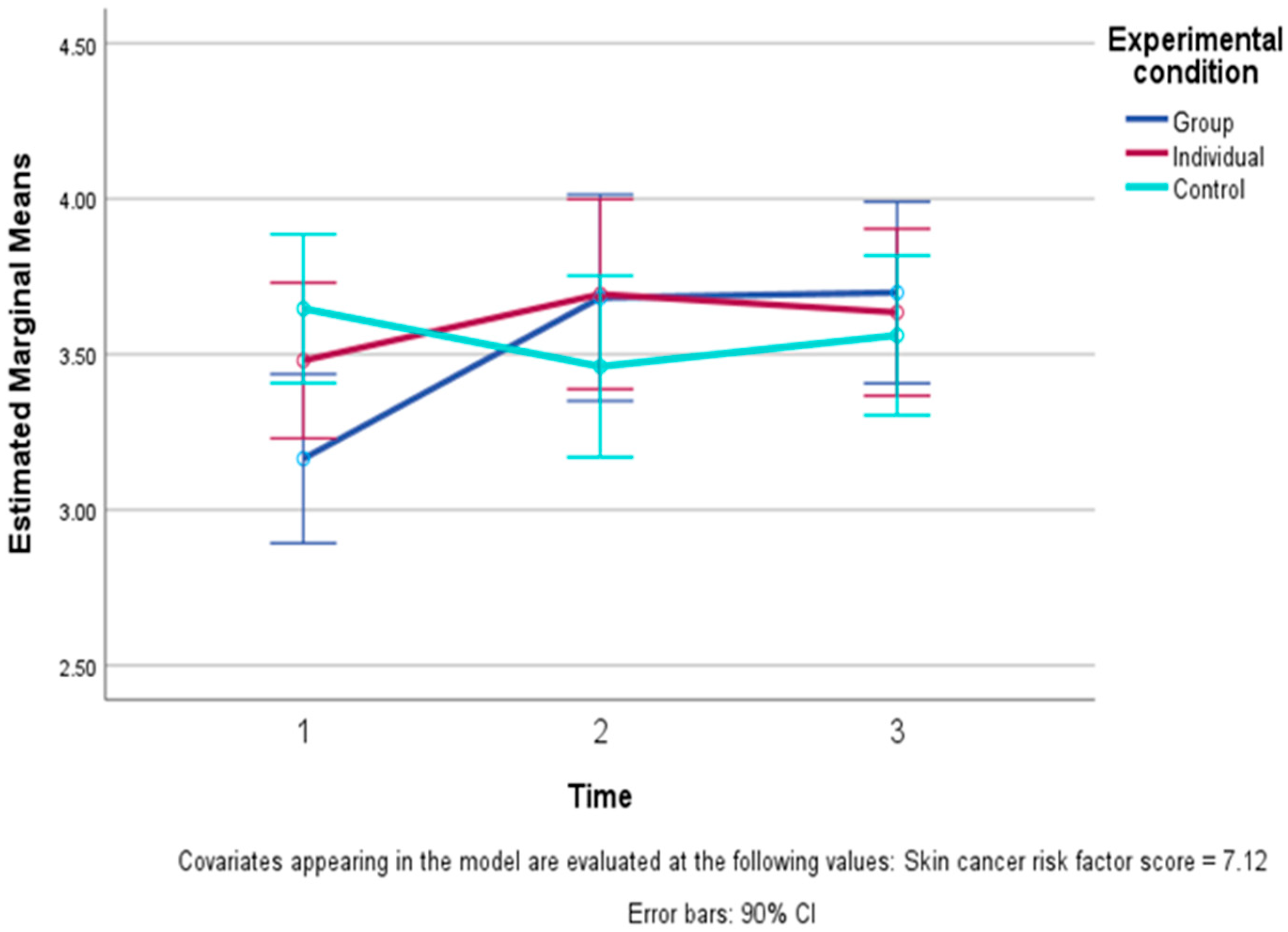

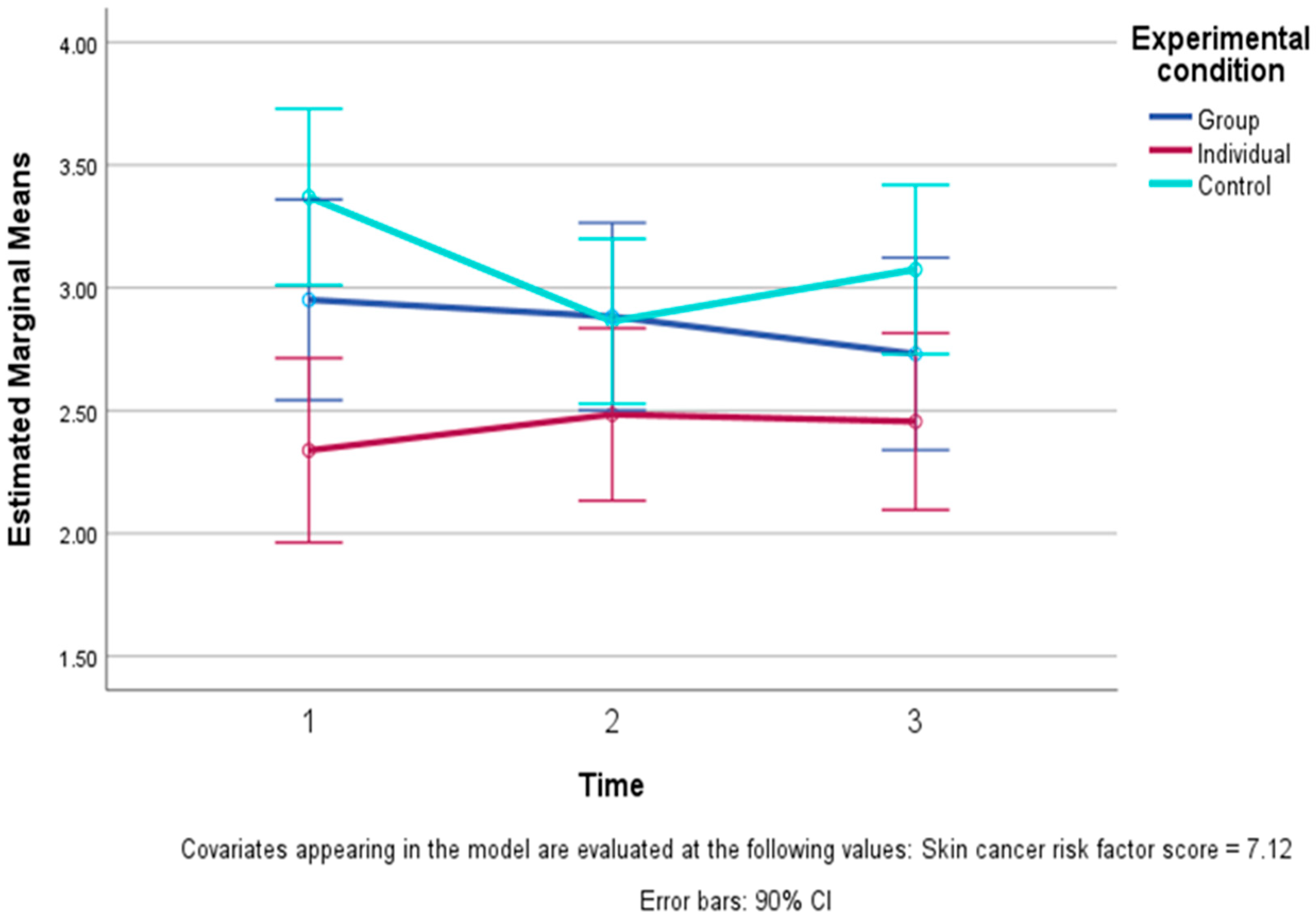

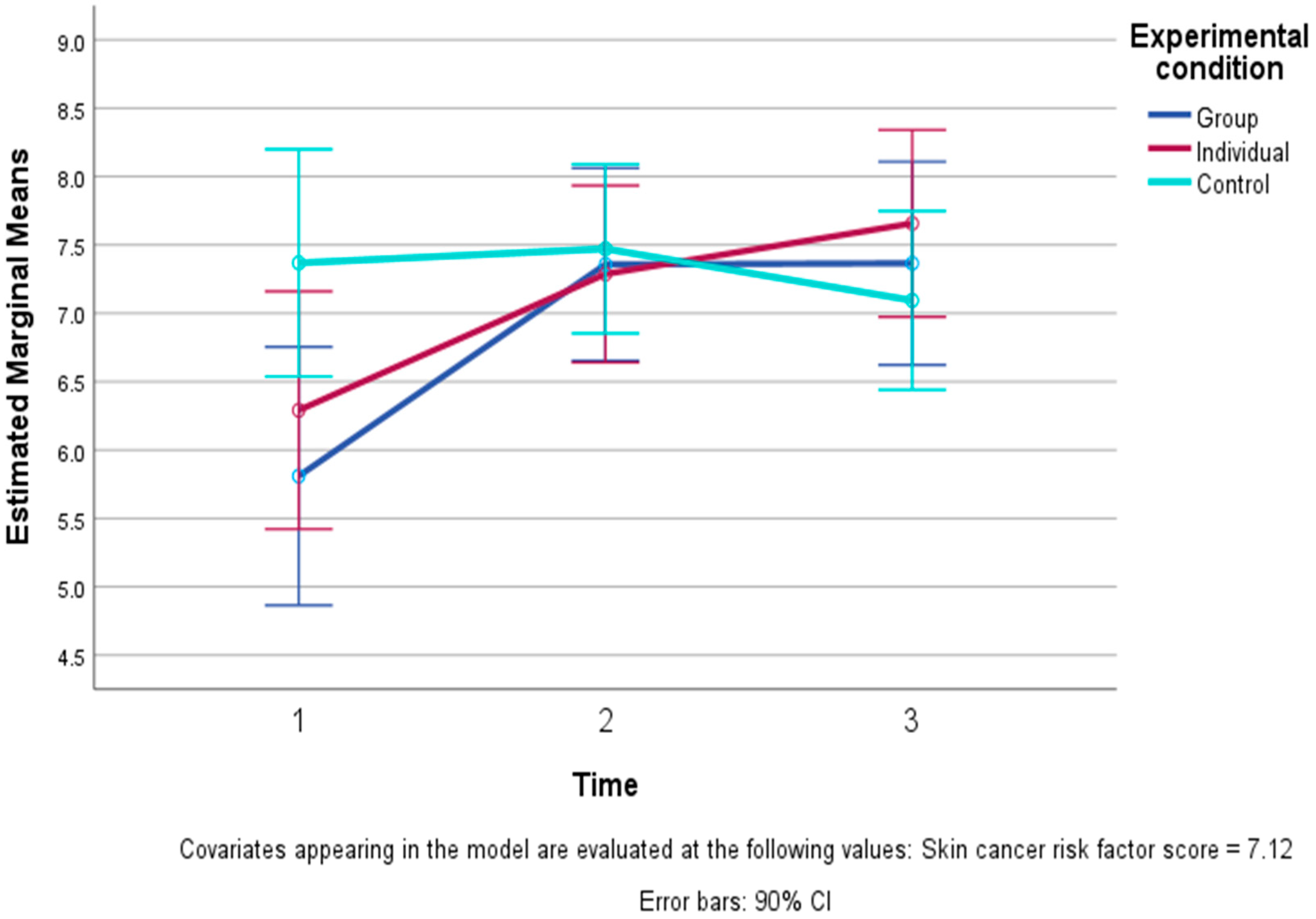

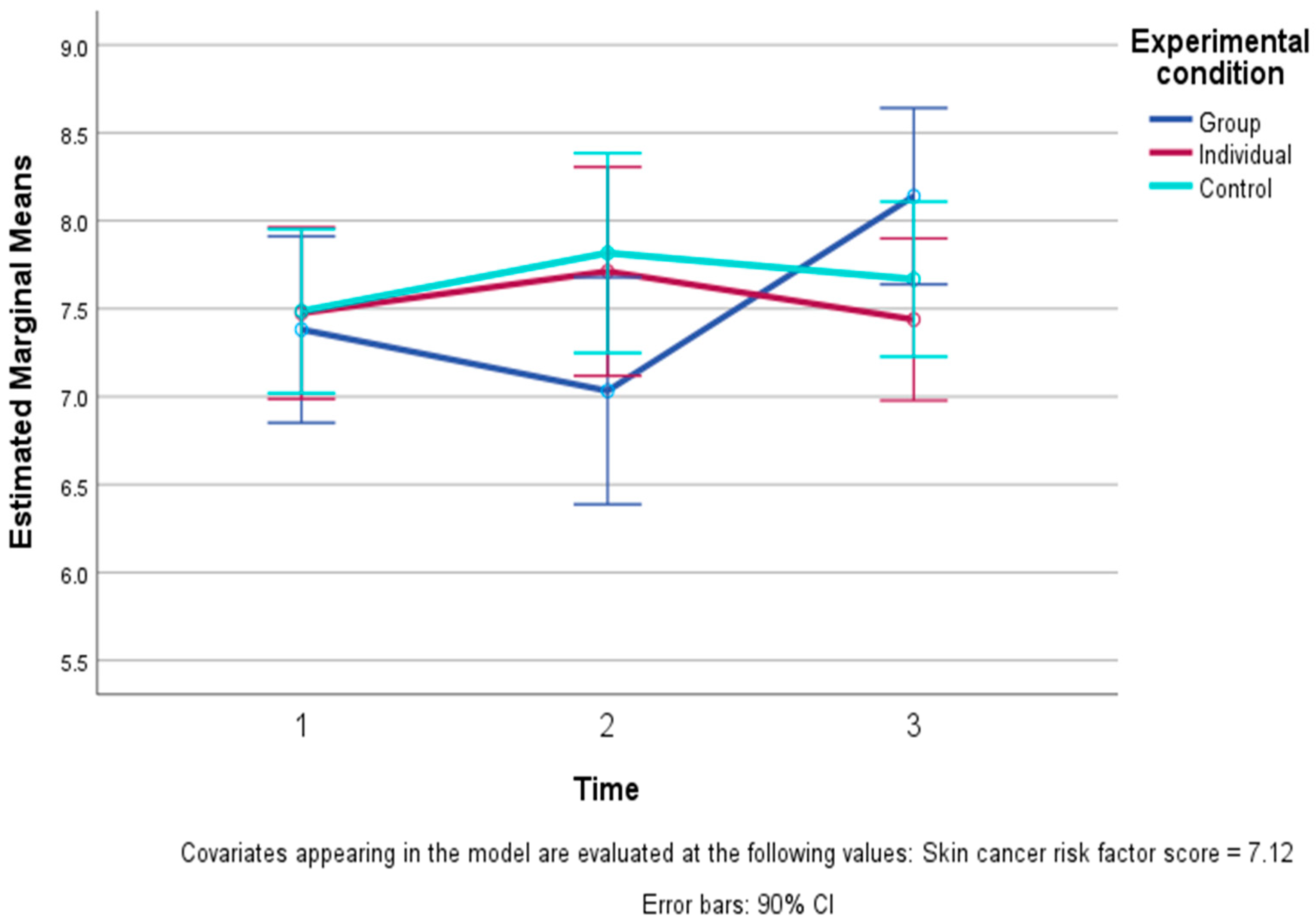

3.2. Differences Among the Study Conditions over Time

3.3. Changes in Subjective Unit of Distress (SUD) Scores

3.4. Participant Satisfaction with EFT Instruction and Practice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC | Control Condition |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| EFT | Emotion Freedom Technique |

| G-EFT | Group Instruction of EFT |

| I-EFT | Individual Instruction of EFT |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SUD | Standard Unit of Distress |

Appendix A

| Study Condition Variable | (a) Group and Individual EFT Conditions—Only Those Who Still Practiced EFT at T3 (b) Full Sample | Group EFT n = 10 n = 15 | Individual EFT n = 10 n = 18 | Control n = 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of cancer recurrence | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | −0.43 −0.23 | −0.36 −0.22 | −0.31 |

| Happiness | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.41 0.54 | 0.33 −0.14 | 0.23 |

| Wellbeing—mean of five items | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.57 0.64 | 0.46 0.48 | −0.10 |

| Physical wellbeing | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.31 0.17 | 0.09 0.15 | −0.10 |

| Mental wellbeing | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.54 0.44 | −0.00 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Relational wellbeing | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.32 0.35 | 0.26 0.23 | −0.24 |

| Spiritual wellbeing | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.53 0.65 | 0.70 0.57 | 0.03 |

| General wellbeing | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.60 0.58 | 0.78 0.35 | −0.14 |

| Consequences | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | −0.47 −0.34 | 0.22 0.28 | −0.07 |

| Controllability | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.15 −0.06 | 0.12 0.17 | −0.31 |

| Coherence | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | 0.85 0.75 | 0.23 0.37 | −0.22 |

| Emotional representations | (a) Practicing at T3 (b) Full sample | −0.39 −0.11 | −0.32 0.02 | −0.38 |

References

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; de Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global burden of cutaneous melanoma in 2020 and projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidler, M.M.; Gupta, S.; Soerjomataram, I.; Ferlay, J.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality among young adults aged 20–39 years worldwide in 2012: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, D.; Holterhues, C.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Coebergh, J.W.; Nijsten, T. A systematic review of health-related quality of life in cutaneous melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, vi51–vi58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist Bagge, A.S.; Wesslau, H.; Cizek, R.; Holmberg, C.J.; Moncrieff, M.; Katsarelias, D.; Carlander, A.; Olofsson Bagge, R. Health-related quality of life using the FACT-M questionnaire in patients with malignant melanoma: A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.E.; Butow, P.N.; Culjak, G.; Coates, A.S.; Dunn, S.M. Psychosocial predictors of outcome: Time to relapse and survival in patients with early stage melanoma. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 83, 1448–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butow, P.N.; Coates, A.S.; Dunn, S.M. Psychosocial predictors of survival in metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 2256–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerling, A.; Ricon-Becker, I.; Sorski, L.; Sandbank, E.; Ben-Eliyahu, S. Stress and cancer: Mechanisms, significance and future directions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, B.; Fang, F.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.; Udumyan, R.; Montgomery, S.; Fall, K. Stress resilience and cancer risk: A nationwide cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Kaminga, A.C.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Xu, H. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of cancer during adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child. Abuse Negl. 2021, 117, 105088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromanoli, A.; Sikorski, C.; Behzad, D.; Manji, K.; Kreatsoulas, C. Adverse childhood experiences and cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 10565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, B.K.; Zheng, A.; Erickson, K.L.; Bordeaux, J.S. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) association with Melanoma. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidlo, N.; Lazarov, A.; Benyamini, Y. Stressful life events and the occurrence of skin cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2024, 33, e6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeke, C.A.; Williams, J.P.; Tran, J.H.; Byrd, A.S. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and associated health outcomes among adults with skin cancer. J. Dermat. Cosmetol. 2023, 7, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Glaser, R.; Johnson, S.L.; Andridge, R.R.; Yang, E.V.; Di Gregorio, M.P.; Chen, M.; Lambert, D.R.; Jewell, S.D.; Bechtel, M.A.; et al. Basal Cell Carcinoma: Stressful life events and the tumor environment. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasparian, N.A.; McLoone, J.K.; Butow, P.N. Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: A systematic review of the literature. Arch. Dermatol. 2009, 145, 1415–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richtig, E.; Trapp, E.M.; Avian, A.; Brezinsek, H.P.; Trapp, M.; Egger, J.W.; Kapfhammer, H.; Rohrer, P.; Berghold, A.; Curiel-Lewandrowski, C.; et al. Psychological stress and immunological modulations in early-stage melanoma patients. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2015, 95, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesio, V.; Ribero, S.; Castelli, L.; Bassino, S.; Leombruni, P.; Caliendo, V.; Grassi, M.; Lauro, D.; Macripò, G.; Torta, R.G.V. Psychological characteristics of early-stage melanoma patients: A cross-sectional study on 204 patients. Melanoma Res. 2017, 27, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscano, A.; Blanchin, M.; Bourdon, M.; Bonnaud Antignac, A.; Sébille, V. Longitudinal associations between coping strategies, locus of control and health-related quality of life in patients with breast cancer or melanoma. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Vasudevan, A.; O’Keefe, T. Clinical EFT as an evidence-based practice for the treatment of psychological and physiological conditions: A systematic review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 951451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D. Clinical EFT as an evidence-based practice for the treatment of psychological and physiological conditions. Psychology 2013, 4, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittfoth, D.; Beise, J.; Manuel, J.; Bohne, M.; Wittfoth, M. Bifocal emotion regulation through acupoint tapping in fear of flying. NeuroImage Clin. 2022, 34, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittfoth, D.; Pfeiffer, A.; Bohne, M.; Lanfermann, H.; Wittfoth, M. Emotion regulation through bifocal processing of fear inducing and disgust inducing stimuli. BMC Neurosci. 2020, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, D. Integrating the manual stimulation of acupuncture points into psychotherapy: A systematic review with clinical recommendations. J. Psychother. Integr. 2023, 33, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedom, J.; Hux, M.; Warner, J. Research on acupoint tapping therapies proliferating around the world. Energy Psychol. 2022, 14, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, D. Six empirically-supported premises about Energy Psychology: Mounting evidence for a controversial therapy. Adv. Mind Body Med. 2021, 35, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Church, D. The EFT Manual, 4th ed.; Energy Psychology Press: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Church, D.; Feinstein, D. The manual stimulation of acupuncture points in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of clinical Emotional Freedom Techniques. Med. Acupunct. 2017, 29, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Stapleton, P.; Yang, A.; Gallo, F. Is tapping on acupuncture points an active ingredient in Emotional Freedom Techniques? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2018, 206, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Nelms, J. Pain, range of motion, and psychological symptoms in a population with frozen shoulder: A randomized controlled dismantling study of clinical EFT (emotional freedom techniques). Arch. Sci. Psychol. 2016, 4, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattberg, G. Self-administered EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) in individuals with fibromyalgia: A randomized trial. Integr. Med. 2008, 7, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Church, D. Reductions in pain, depression, and anxiety symptoms after PTSD remediation in veterans. EXPLORE 2014, 10, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Brooks, A.J. The effect of a brief emotional freedom techniques self-intervention on anxiety, depression, pain, and cravings in health care workers. Integr. Med. 2010, 9, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ortner, N.; Palmer-Hoffman, J.; Clond, M. Effects of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) on the reduction of chronic pain in adults: A pilot study. Energy Psychol. J. 2014, 6, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P. Emotional freedom techniques for chronic pain: An investigation of self-paced vs. live delivery (including fMRI). In Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Energy Psychology Research Symposium, Taos, NM, USA, 11 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, P.; Bannatyne, A.J.; Urzi, K.-C.; Porter, B.; Sheldon, T. Food for thought: A randomised controlled trial of Emotional Freedom Techniques and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in the treatment of food cravings. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2016, 8, 232–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, P.; Chatwin, H. Emotional Freedom Techniques for food cravings in overweight adults: A comparison of treatment length. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2018, 3, 014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Palmer-Hoffman, J. TBI symptoms improve after PTSD remediation with emotional freedom techniques. Traumatology 2014, 20, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, D.; Groesbeck, G.; Stapleton, P.; Sims, R.; Blickheuser, K.; Church, D. Clinical EFT (Emotional Freedom Techniques) improves multiple physiological markers of health. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2019, 24, 2515690X18823691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharaj, M. Differential Gene Expression after Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) Treatment: A Novel Pilot Protocol for Salivary mRNA Assessment. Energy Psychol. J. 2016, 8, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Yount, G.; Rachlin, K.; Fox, L.; Nelms, J. Epigenetic effects of PTSD remediation in veterans using clinical Emotional Freedom Techniques: A randomized controlled pilot study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, D.; Yount, G.; Brooks, A.J. The effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques on stress biochemistry: A randomized controlled trial. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2012, 200, 891–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P.; Crighton, G.; Sabot, D.; O’Neill, H.M. Reexamining the effect of Emotional Freedom Techniques on stress biochemistry: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol. Trauma. 2020, 12, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swingle, P. Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT) as an effective adjunctive treatment in the neurotherapeutic treatment of seizure disorders. Energy Psychol. J. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P.; Buchan, C.; Mitchell, I.; McGrath, Y.; Gorton, P.; Carter, B. An initial investigation of neural changes in overweight adults with food cravings after Emotional Freedom Techniques. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2019, 4, 010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yount, G.; Church, D.; Rachlin, K.; Blickheuser, K.; Cardonna, I. Do noncoding RNAs mediate the efficacy of Energy Psychology? Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2019, 8, 2164956119832500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.S.; Hoffman, C.J. Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) to reduce the side effects associated with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor use in women with breast cancer: A service evaluation. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2015, 7, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, J. Effect of emotional freedom technique on perceived stress, anxiety and depression in cancer patients: A preliminary experiment. Mod. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 16, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalroozi, F.; Moradi, M.; Ghaedi-Heidari, F.; Marzban, A.; Raeisi-Ardali, S.R. Comparing the effect of emotional freedom technique on sleep quality and happiness of women undergoing breast cancer surgery in military and nonmilitary families: A quasi-experimental multicenter study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 2986–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tack, L.; Lefebvre, T.; Lycke, M.; Langenaeken, C.; Fontaine, C.; Borms, M.; Hanssens, M.; Knops, C.; Meryck, K.; Boterberg, T.; et al. A randomised wait-list controlled trial to evaluate Emotional Freedom Techniques for self-reported cancer-related cognitive impairment in cancer survivors (EMOTICON). eClinicalMedicine 2021, 39, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakam, M.; Yetti, K.; Hariyati, R.T.S. Spiritual Emotional Freedom Technique Intervention to reduce pain in cancer patients. Makara J. Health Res. 2009, 13, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacchi, A.; Chiesi, F.; Lau, C.; Marunic, G.; Saklofske, D.H.; Marra, F.; Miccinesi, G.; Gremigni, P. Rapid and sound assessment of well-being within a multi-dimensional approach: The Well-being Numerical Rating Scales (WB-NRSs). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Basic Documents; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Balboni, T.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Doan-Soares, S.D.; Long, K.N.G.; Ferrell, B.R.; Fitchett, G.; Koenig, H.G.; Bain, P.A.; Puchalski, C.; Steinhauser, K.E.; et al. Spirituality in serious illness and health. JAMA 2022, 328, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Koch, S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Orbell, S. The common sense model of self-regulation: Meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1117–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyamini, Y.; Goner-Shilo, D.; Lazarov, A. Illness perception and quality of life in patients with contact dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 2012, 67, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leventhal, H.; Benyamini, Y.; Brownlee, S.; Diefenbach, M.; Leventhal, E.A.; Patrick-Miller, L.; Robitaille, C. Illness representations: Theoretical foundations. In Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications; Petrie, K.J., Weinman, J., Eds.; Harwood Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, H.; Meyer, D.; Nerenz, D.R. The common sense representation of illness danger. In Contributions to Medical Psychology; Rachman, S., Ed.; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, E.M.; Schüz, N.; Sanderson, K.; Scott, J.L.; Schüz, B. Illness representations, coping, and illness outcomes in people with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 724–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Rooij, B.H.; Thong, M.S.Y.; van Roij, J.; Bonhof, C.S.; Husson, O.; Ezendam, N.P.M. Optimistic, realistic, and pessimistic illness perceptions; quality of life; and survival among 2457 cancer survivors: The population-based PROFILES registry. Cancer 2018, 124, 3609–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozema, H.; Völlink, T.; Lechner, L. The role of illness representations in coping and health of patients treated for breast cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2009, 18, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, T.; Aktas, G.; Ekici, H.; Elboga, G.; Djamgoz, S. Illness perception is a strong parameter on anxiety and depression scores in early-stage breast cancer survivors: A single-center cross-sectional study of Turkish patients. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 3347–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Walker, A.; MacLeod, M.J. Patient compliance in hypertension: Role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2004, 18, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, L.; Marti, J.; Jones, H.; Velikova, G.; Wright, P. Illness perceptions within 6 months of cancer diagnosis are an independent prospective predictor of health-related quality of life 15 months post-diagnosis. Psycho-Oncol. 2015, 24, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, M.; McCorry, N.K.; Brennan, E.; Donnelly, M.; Murray, L.J.; Johnston, B.T. Do changes in illness perceptions predict changes in psychological distress among oiesophageal cancer survivors? J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, L.B.; Robbins, L.; Mancuso, C.A.; Charlson, M.E. How do cancer patients who try to take control of their disease differ from those who do not? Eur. J. Cancer Care 2004, 13, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henselmans, I.; Sanderman, R.; Helgeson, V.S.; de Vries, J.; Smink, A.; Ranchor, A.V. Personal control over the cure of breast cancer: Adaptiveness, underlying beliefs and correlates. Psycho-Oncol. 2010, 19, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corter, A.L.; Findlay, M.; Broom, R.; Porter, D.; Petrie, K.J. Beliefs about medicine and illness are associated with fear of cancer recurrence in women taking adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman-Gibb, L.A.; Janz, N.K.; Katapodi, M.C.; Zikmund-Fisher, B.J.; Northouse, L. The relationship between illness representations, risk perception and fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 1270–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llewellyn, C.D.; Weinman, J.; McGurk, M.; Humphris, G. Can we predict which head and neck cancer survivors develop fears of recurrence? J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 65, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durazo, A.; Cameron, L.D. Representations of cancer recurrence risk, recurrence worry, and health-protective behaviours: An elaborated, systematic review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2019, 13, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nausheen, B.; Gidron, Y.; Peveler, R.; Moss-Morris, R. Social support and cancer progression: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 67, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, B.N.; Bowen, K.; Carlisle, M.; Birmingham, W. Psychological pathways linking social support to health outcomes: A visit with the “ghosts” of research past, present, and future. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Park, C. The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Ponte, M.; Ferreira, G.; Machado, J.C. Quality of life in patients with skin tumors: The mediator role of body image and social support. Psycho-Oncol. 2017, 26, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Baek, J.-M.; Jeon, Y.-W.; Im, E.-O. Illness perception and sense of well-being in breast cancer patients. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2019, 13, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvogli, L.; Darviri, C. Stress Management Techniques: Evidence-based procedures that reduce stress and promote health. Health Sci. J. 2011, 5, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Køster, B.; Søndergaard, J.; Nielsen, J.B.; Allen, M.; Olsen, A.; Bentzen, J. The validated sun exposure questionnaire: Association of objective and subjective measures of sun exposure in a Danish population-based sample. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 176, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godin, G.; Shephard, R.J. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can. J. Appl. Sport. Sci. 1985, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2006, 34, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zur, H. Coping, affect and aging: The roles of mastery and self-esteem. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2002, 32, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, S.; Savard, J. Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: Development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 17, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, S.; Savard, J. Screening and comorbidity of clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, G.; Zamir, O.; Dahabre, R.; Perry, S.; Karademas, E.C.; Poikonen-Saksela, P.; Mazzocco, K.; Sousa, B.; Pat-Horenczyk, R. Protective factors against fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer patients: A latent growth model. Cancers 2023, 15, 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, G.; Zamir, O.; Roziner, I.; Dahabre, R.; Perry, S.; Karademas, E.C.; Poikonen-Saksela, P.; Mazzocco, K.; Oliveira-Maia, A.J.; Pat-Horenczyk, R. Fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer: A moderated serial mediation analysis of a prospective international study. Health Psychol. 2024, 43, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, L.; Smith, A.B.; Keding, A.; Jones, H.; Velikova, G.; Wright, P. Psychometric evaluation of the Revised Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ-R) in cancer patients: Confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2013, 75, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, Z.; Moss-Morris, R.; Hunter, M.S.; Hughes, L.D. Measuring illness representations in breast cancer survivors (BCS) prescribed tamoxifen: Modification and validation of the Revised Illness Perceptions Questionnaire (IPQ-BCS). Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a new General Self-Efficacy Scale. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpe, J. The Practice of Behavior Therapy, 4th ed.; Pergamon Press: Elmsford, NY, USA, 1990; pp. xvi, 421. [Google Scholar]

- Thyer, B.A.; Papsdorf, J.D.; Davis, R.; Vallecorsa, S. Autonomic correlates of the subjective anxiety scale. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1984, 15, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheeringa, M.S.; Zeanah, C.H.; Myers, L.; Putnam, F. Heart period and variability findings in preschool children with posttraumatic stress symptoms. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 55, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.L.; Silver, S.M.; Covi, W.G.; Foster, S. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Effectiveness and autonomic correlates. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1996, 27, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D.M.; Ports, K.A.; Buchanan, N.D.; Hawkins, N.A.; Merrick, M.T.; Metzler, M.; Trivers, K.F. The association between adverse childhood experiences and risk of cancer in adulthood: A systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics 2016, 138, S81–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnya, S.; De’Ambrosis, B. Stress and melanoma: Increasing the evidence towards a causal basis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 305, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanzo, M.; Colucci, R.; Arunachalam, M.; Berti, S.; Moretti, S. Stress as a possible mechanism in melanoma progression. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2010, 2010, 483493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, H.; Lin, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, F. Spiritual needs of older adults with cancer: A modified concept analysis. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, D.P. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stripp, T.A.; Wehberg, S.; Büssing, A.; Koenig, H.G.; Balboni, T.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Søndergaard, J.; Hvidt, N.C. Spiritual needs in Denmark: A population-based cross-sectional survey linked to Danish national registers. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 28, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, Y.; Hu, R. The effects of spiritual care on quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bożek, A.; Nowak, P.F.; Blukacz, M. The relationship between spirituality, health-related behavior, and psychological well-being. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kim, E.S.; VanderWeele, T.J. Religious-service attendance and subsequent health and well-being throughout adulthood: Evidence from three prospective cohorts. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 2030–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekierda, K.; Banik, A.; Park, C.L.; Luszczynska, A. Meaning in life and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2017, 11, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Thoresen, C.E. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Church, D.; Vasudevan, A.; DeFoe, A. The association of relational spirituality in an EcoMeditation course with flow, transcendent states, and professional productivity. Adv. Mind Body Med. 2024, 38, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koenig, H.G.; McCullough, M.E.; Larson, D.B. Handbook of Religion and Health; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeller, J.L.; Sheets, V.; Johnson, T.; Frank, B. Understanding religious and spiritual influences on adjustment to cancer: Individual patterns and differences. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 34, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.L.; Masters, K.S.; Salsman, J.M.; Wachholtz, A.; Clements, A.D.; Salmoirago-Blotcher, E.; Trevino, K.; Wischenka, D.M. Advancing our understanding of religion and spirituality in the context of behavioral medicine. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 40, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisesrith, W.; Sukcharoen, P.; Sripinkaew, K. Spiritual care needs of Terminal Ill cancer patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 3773–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, H.S.; Olver, I.N.; Peterson, M.J. Spirituality as a core domain in the assessment of quality of life in oncology. Psycho-Oncol. 2008, 17, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P.; Kip, K.; Church, D.; Toussaint, L.; Footman, J.; Ballantyne, P.; O’Keefe, T. Emotional Freedom Techniques for treating post traumatic stress disorder: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1195286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P. Preliminary Support for Emotional Freedom Techniques as a Support for Cancer Patients. Foundation for Alternative and Integrative Medicine. Available online: https://www.faim.org/preliminary-support-for-emotional-freedom-techniques-as-a-support-for-cancer-patients (accessed on 3 January 2024).

| Variable | Group EFT Instruction (n = 16) | Individual EFT Instruction (n = 18) | Waiting-List Control Condition (n = 19) | All (N = 53) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 81.3 (13) | 66.7 (12) | 68.4 (13) | 71.7 (38) |

| Male | 18.7 (3) | 33.3 (6) | 31.6 (6) | 28.3 (15) |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed | 62.5 (10) | 66.7 (12) | 68.4 (13) | 66.0 (35) |

| Unemployed or fully retired | 37.5 (6) | 33.3 (6) | 31.6 (6) | 34.0 (18) |

| Education level | ||||

| Partial high school | 0.0 (0) | 5.6 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1.9 (1) |

| High school graduate | 0.0 (0) | 11.1 (2) | 15.8 (3) | 9.4 (5) |

| Non-academic higher education | 18.7 (3) | 11.1 (2) | 15.8 (3) | 15.1 (8) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 31.3 (5) | 33.3 (6) | 31.6 (6) | 32.1 (17) |

| Master’s or doctoral degree | 50.0 (8) | 38.9 (7) | 36.8 (7) | 41.5 (22) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or cohabiting | 81.2 (13) | 100.0 (18) | 84.2 (16) | 88.7 (47) |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 12.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 10.5 (2) | 7.5 (4) |

| Single | 6.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 5.3 (1) | 3.8 (2) |

| Income level (n = 51) | ||||

| Below average | 6.7 (1) | 5.9 (1) | 5.2 (1) | 5.9 (3) |

| Average | 33.3 (5) | 17.6 (3) | 47.4 (9) | 33.3 (17) |

| Above average | 60.0 (9) | 76.5 (13) | 47.4 (9) | 60.8 (31) |

| Religion | ||||

| Secular | 93.8 (15) | 88.9 (16) | 84.2 (16) | 88.7 (47) |

| Traditional or religious | 6.2 (1) | 11.1 (3) | 15.8 (3) | 11.3 (6) |

| Measure (Scale) | Study Condition a | T1—Baseline | T2—End of Intervention b | T3—Three Months Later | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Happiness (0–10) | Group | 7.44 | 0.96 | 7.19 | 1.94 | 8.13 | 0.74 |

| Individual | 7.39 | 1.34 | 7.61 | 1.20 | 7.44 | 1.42 | |

| Control | 7.58 | 1.17 | 7.83 | 1.04 | 7.74 | 0.99 | |

| Total | 7.47 | 1.15 | 7.56 | 1.42 | 7.75 | 1.12 | |

| Negative affect (1–5) | Group | 2.18 | 0.67 | 2.04 | 0.90 | 2.24 | 0.46 |

| Individual | 2.22 | 1.02 | 2.02 | 0.74 | 2.18 | 0.76 | |

| Control | 2.07 | 0.75 | 1.99 | 0.52 | 1.97 | 0.54 | |

| Total | 2.15 | 0.82 | 2.02 | 0.71 | 2.12 | 0.61 | |

| Positive affect (1–5) | Group | 3.24 | 0.84 | 3.29 | 0.67 | 3.41 | 0.77 |

| Individual | 3.16 | 0.68 | 3.12 | 0.85 | 3.09 | 0.84 | |

| Control | 2.97 | 0.61 | 3.03 | 0.62 | 3.03 | 0.79 | |

| Total | 3.11 | 0.71 | 3.14 | 0.72 | 3.16 | 0.80 | |

| Self-efficacy (1–5) | Group | 3.87 | 0.51 | 3.97 | 0.39 | 4.03 | 0.44 |

| Individual | 3.89 | 0.65 | 3.98 | 0.48 | 3.86 | 0.58 | |

| Control | 3.77 | 0.56 | 3.84 | 0.41 | 3.88 | 0.50 | |

| Total | 3.84 | 0.57 | 3.92 | 0.43 | 3.92 | 0.51 | |

| Wellbeing—mean of five items (1–10) | Group | 7.15 | 1.07 | 7.49 | 0.99 | 7.88 | 0.75 |

| Individual | 7.46 | 1.14 | 7.86 | 1.02 | 7.92 | 1.21 | |

| Control | 7.75 | 1.04 | 7.71 | 1.04 | 7.66 | 0.82 | |

| Total | 7.47 | 1.09 | 7.69 | 1.01 | 7.82 | 0.95 | |

| Physical wellbeing (1–10) | Group | 7.50 | 1.32 | 7.50 | 1.15 | 7.73 | 1.22 |

| Individual | 7.78 | 1.31 | 7.89 | 1.18 | 7.94 | 1.39 | |

| Control | 7.63 | 1.46 | 7.72 | 1.18 | 7.47 | 1.12 | |

| Total | 7.64 | 1.35 | 7.71 | 1.16 | 7.71 | 1.24 | |

| Mental wellbeing (1–10) | Group | 7.25 | 1.24 | 7.19 | 1.83 | 7.93 | 0.88 |

| Individual | 7.39 | 1.91 | 7.78 | 1.31 | 7.61 | 1.54 | |

| Control | 7.84 | 1.39 | 7.44 | 1.25 | 7.89 | 0.88 | |

| Total | 7.51 | 1.54 | 7.48 | 1.46 | 7.81 | 1.14 | |

| Relational wellbeing (1–10) | Group | 7.75 | 1.43 | 7.94 | 1.18 | 8.27 | 1.16 |

| Individual | 8.28 | 1.02 | 8.33 | 0.77 | 8.50 | 0.79 | |

| Control | 8.26 | 1.28 | 8.17 | 1.25 | 8.00 | 1.45 | |

| Total | 8.11 | 1.25 | 8.15 | 1.07 | 8.25 | 1.17 | |

| Spiritual wellbeing (1–10) | Group | 5.81 | 2.37 | 7.13 | 1.20 | 7.47 | 1.46 |

| Individual | 6.17 | 2.15 | 7.44 | 1.62 | 7.56 | 1.79 | |

| Control | 7.11 | 2.08 | 7.44 | 1.79 | 7.16 | 1.61 | |

| Total | 6.40 | 2.22 | 7.35 | 1.55 | 7.38 | 1.61 | |

| General wellbeing (1–10) | Group | 7.44 | 1.03 | 7.69 | 0.79 | 8.00 | 0.65 |

| Individual | 7.67 | 1.09 | 7.83 | 0.99 | 8.00 | 1.41 | |

| Control | 7.89 | 1.05 | 7.78 | 1.06 | 7.79 | 0.79 | |

| Total | 7.68 | 1.05 | 7.77 | 0.94 | 7.92 | 1.01 | |

| Fear of cancer recurrence (0–4) | Group | 1.57 | 0.65 | 1.43 | 0.56 | 1.42 | 0.69 |

| Individual | 1.19 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 0.76 | 1.10 | 0.73 | |

| Control | 1.56 | 0.48 | 1.36 | 0.63 | 1.40 | 0.65 | |

| Total | 1.43 | 0.69 | 1.30 | 0.66 | 1.31 | 0.69 | |

| Consequences (1–5) | Group | 3.18 | 1.44 | 2.60 | 1.33 | 2.80 | 1.40 |

| Individual | 2.28 | 1.04 | 2.56 | 1.27 | 2.52 | 1.18 | |

| Control | 3.05 | 1.33 | 2.91 | 1.29 | 2.95 | 1.27 | |

| Total | 2.83 | 1.32 | 2.69 | 1.28 | 2.76 | 1.27 | |

| Controllability (1–5) | Group | 4.03 | 0.33 | 4.05 | 0.49 | 3.97 | 0.47 |

| Individual | 3.84 | 0.54 | 3.91 | 0.43 | 3.94 | 0.51 | |

| Control | 3.88 | 0.59 | 3.94 | 0.47 | 3.76 | 0.66 | |

| Total | 3.91 | 0.51 | 3.97 | 0.46 | 3.88 | 0.56 | |

| Coherence (1–5) | Group | 3.25 | 0.52 | 3.69 | 0.57 | 3.67 | 0.47 |

| Individual | 3.44 | 0.62 | 3.70 | 0.72 | 3.67 | 0.70 | |

| Control | 3.64 | 0.66 | 3.46 | 0.84 | 3.51 | 0.71 | |

| Total | 3.45 | 0.61 | 3.62 | 0.72 | 3.61 | 0.64 | |

| Emotional representations c (1–5) | Group | 3.02 | 0.86 | 3.08 | 0.82 | 2.87 | 0.80 |

| Individual | 2.31 | 1.14 | 2.33 | 1.03 | 2.32 | 1.18 | |

| Control | 3.37 | 0.57 | 2.89 | 0.79 | 3.11 | 0.59 | |

| Total | 2.90 | 0.98 | 2.75 | 0.93 | 2.76 | 0.94 | |

| How Satisfied Are You with the Instruction on EFT? | Group Instruction (n = 15) | Individual Instruction (n = 18) | Total (n = 33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| A little bit | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Moderately | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Quite a lot | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Very much | 9 | 11 | 20 |

| Total | 15 | 18 | 33 |

| End of Intervention | Three Months Later | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Times a Week | Group Instruction | Individual Instruction | Total | Group Instruction | Individual Instruction | Total |

| 0 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| 1–2 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 3–5 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| 6–7 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 16 | 18 | 34 | 15 | 18 | 33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazarov, A.; Church, D.; Shidlo, N.; Benyamini, Y. The Effectiveness of Group and Individual Training in Emotional Freedom Techniques for Patients in Remission from Melanoma: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121420

Lazarov A, Church D, Shidlo N, Benyamini Y. The Effectiveness of Group and Individual Training in Emotional Freedom Techniques for Patients in Remission from Melanoma: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare. 2025; 13(12):1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121420

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazarov, Aneta, Dawson Church, Noa Shidlo, and Yael Benyamini. 2025. "The Effectiveness of Group and Individual Training in Emotional Freedom Techniques for Patients in Remission from Melanoma: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Healthcare 13, no. 12: 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121420

APA StyleLazarov, A., Church, D., Shidlo, N., & Benyamini, Y. (2025). The Effectiveness of Group and Individual Training in Emotional Freedom Techniques for Patients in Remission from Melanoma: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare, 13(12), 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13121420