Unpacking Young Adults’ Fact-Checking Intent on Oral Health Misinformation: Parallel Mediating Roles of Need for Cognition and Perceived Seriousness—A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theory of Status Quo Bias

2.2. Oral Health Misinformation in Short Videos and Its Impact in China

2.3. Exploring the Relationships Among MR, NFC, and PS

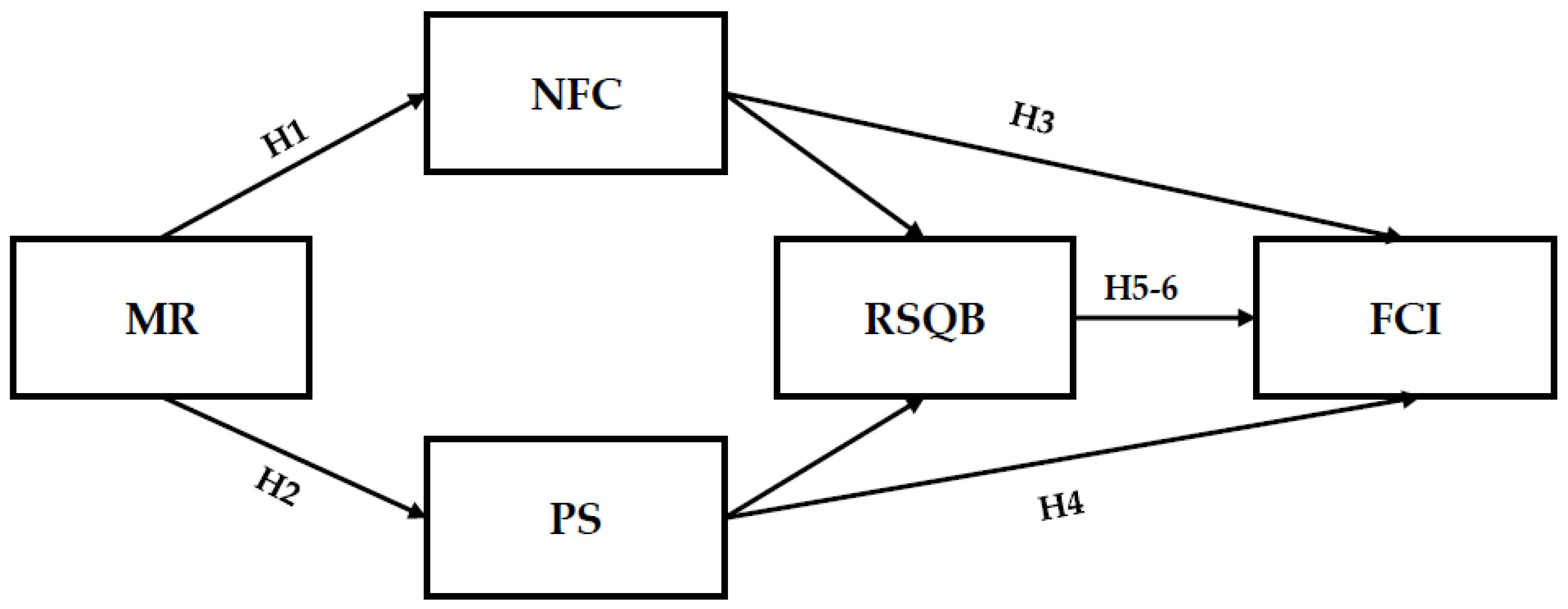

2.4. Parallel Mediation Model: The Roles of NFC and PS

2.5. The Serial Mediating Role of Psychological Factors and RSQB

3. Methods

3.1. Measurements

3.2. Data Collection Procedures

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Data

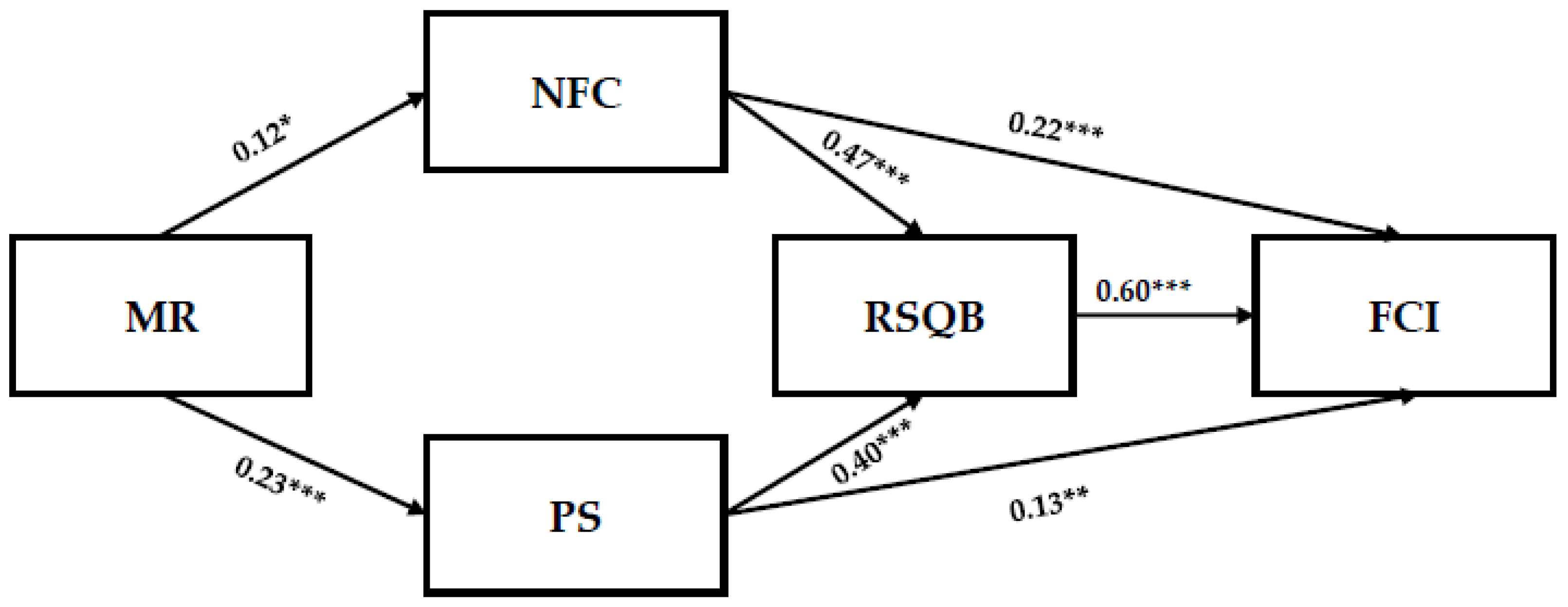

4.2. Path Analysis Tests

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Source | Items | Loading | α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | [59,60] | I think the contents are inaccurate. | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.98 | 0.81 |

| I think the sources of these contents are unreliable. | 0.91 | |||||

| I think the providers of these contents have low credibility. | 0.91 | |||||

| Regardless of accuracy, I find these videos suspicious. | 0.88 | |||||

| NFC | [43] | I am willing to give oral health information a lot of thought, even if it takes a long time. | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 0.76 |

| Compared to others, I spend more time thinking about oral health information. | 0.90 | |||||

| I try to make myself think more about issues related to oral health. | 0.91 | |||||

| PS | [61] | Believing in misinformation would be bad for my health. | 0.83 | 0.86 | 00.97 | 0.71 |

| Believing in misinformation would cause me financial loss. | 0.84 | |||||

| Believing in misinformation would reduce my work efficiency. | 0.81 | |||||

| Believing in misinformation would lower my quality of life. | 0.88 | |||||

| RSQB | [62,63] | I generally consider suspicious information carefully and actively fact-check it online. | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.73 |

| I am very willing to proactively fact-check suspicious information. | 0.88 | |||||

| I think it is important to fact-check suspicious information. | 0.86 | |||||

| When people encourage me to fact-check suspicious information, I willingly do so. | 0.83 | |||||

| FCI | [64] | I would fact-check information on short video platforms. | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.97 | 0.52 |

| I would fact-check information through major news organizations. | 0.80 | |||||

| I would fact-check information by consulting friends and family. | 0.70 | |||||

| I would fact-check information using search engines (e.g., Baidu, Google). | 0.70 | |||||

| I would fact-check information through social media (e.g., Weibo, WeChat). | 0.71 | |||||

| I would fact-check information by referring to other sources (e.g., expert opinions, government websites). | 0.70 |

References

- Jin, X.-L.; Yin, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, X. The differential effects of trusting beliefs on social media users’ willingness to adopt and share health knowledge. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, J.R. Health information sharing via social network sites (SNSs): Integrating social support and socioemotional selectivity theory. Health Commun. 2023, 38, 2430–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, C.A.; Olusanya, O.A.; Ammar, N.; Shaban-Nejad, A. Public sentiment analysis and topic modeling regarding COVID-19 vaccines on the Reddit social media platform: A call to action for strengthening vaccine confidence. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farsi, D. Social media and health care, part I: Literature review of social media use by health care providers. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, M.; Smith, B.; Hopwood, D.; Blaauw, R. The use of social media as a source of nutrition information. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 36, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitar-Taut, D.-A.; Mican, D. Social media exposure assessment: Influence on attitudes toward generic vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic. Online Inf. Rev. 2023, 47, 138–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhi, F.; Ghorbani, Z.; Farrokhi, F.; Namdari, M.; Salavatian, S. Social media as a tool for oral health promotion: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0296102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Y.M.; De Moura, G.A.; Desidério, G.A.; De Oliveira, C.H.; Lourenço, F.D.; de Figueiredo Nicolete, L.D. The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, I.; Johnson, S.; Elston Lafata, J. Health information and misinformation: A framework to guide research and practice. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e38687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Newell, R.; Babu, G.R.; Chatterjee, T.; Sandhu, N.K.; Gupta, L. The social media Infodemic of health-related misinformation and technical solutions. Health Policy Technol. 2024, 13, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, O.; Reynolds, T.L.; Ugwuabonyi, E.C.; Joshi, K.P. Exploring the Impact of Increased Health Information Accessibility in Cyberspace on Trust and Self-care Practices. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Workshop on Secure and Trustworthy Cyber-Physical Systems, Porto, Portugal, 21 June 2024; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fan, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, X. Recognizing fake information through a developed feature scheme: A user study of health misinformation on social media in China. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAS. Beijing Advertising Monitoring Report (November 2024). Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/ST0iqeJ_IEMStvXdgdwVQg (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- The Beijing News, in the First Half of the Year, There Were More than 200 Administrative Penalties Related to Oral Institutions, and Illegal Advertising and False Publicity Were Frequent. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1804370188102241660&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Fu, Y. The Teeth of This Generation. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/qGh-XuNKYXNm7NS7KoGLCQ (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Xiao, C. Don’t Fall for the Teenage Tooth Scam Again! Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/E1ctjFX6-HHkJrgT5AWSFA (accessed on 4 August 2022).

- Feng, M. How Much “IQ Tax” Have Young People Been Reaped for a Set of White Teeth? Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/dbe5IQoImhw5QDQA2vrKew (accessed on 5 July 2020).

- Yayibang. Don’t Buy It! All These Popular Dental Products on Tiktok Are Fake. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/zPohLq_nfmzYja_iCFzA5A (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Bautista, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Gwizdka, J. Healthcare professionals’ acts of correcting health misinformation on social media. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 148, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallayil, M.; Nand, P.; Yan, W.Q.; Allende-Cid, H. Explainability of automated fact verification systems: A comprehensive review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, D.; Desens, L.; Guadagno, M.; Tra, Y.; Acker, E.; Sheridan, K.; Rosner, M.; Mathieu, J.; Fulk, M. COVID-19 vaccine discourse on Twitter: A content analysis of persuasion techniques, sentiment and mis/disinformation. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Lledo, V.; Alvarez-Galvez, J. Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e17187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.L.; Ramazan, O. Fact-checking of health information: The effect of media literacy, metacognition and health information exposure. J. Health Commun. 2021, 26, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kožuh, I.; Čakš, P. Social media fact-checking: The effects of news literacy and news trust on the intent to verify health-related information. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, V.; Saxena, K.; Roberts, C.; Kothari, S.; Corman, S.; Yao, L.; Niccolai, L. Impact of reduced human papillomavirus vaccination coverage rates due to COVID-19 in the United States: A model based analysis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2731–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tentori, K.; Pighin, S.; Giovanazzi, G.; Grignolio, A.; Timberlake, B.; Ferro, A. Nudging COVID-19 vaccine uptake by changing the default: A randomized controlled trial. Med. Decis. Mak. 2022, 42, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, W.; Zeckhauser, R. Status quo bias in decision making. J. Risk Uncertain. 1988, 1, 7–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, X.; Wu, Y.; Lai, K.-H.; Vogel, D. Exploring the inhibitors of online health service use intention: A status quo bias perspective. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, A.R.; Sah, S. Amplification of the status quo bias among physicians making medical decisions. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2021, 35, 1374–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, F.; Cannito, L.; Gigliotti, G.; Rosa, A.; Pietroni, D.; Palumbo, R. The joint effect of framing and defaults on choice behavior. Psychol. Res. 2023, 87, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1980, 1, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, G.; Sheppes, G.; Schwartz, C.; Gross, J.J. Patient inertia and the status quo bias: When an inferior option is preferred. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1763–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, J.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Boy, F. Enablers and inhibitors of AI-powered voice assistants: A dual-factor approach by integrating the status quo bias and technology acceptance model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 921–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotis, C.; Allena, M.; Reyes, R.; Romano, A. COVID-19 vaccine passport and international traveling: The combined effect of two nudges on Americans’ support for the pass. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Neal, D.T. Healthy through habit: Interventions for initiating & maintaining health behavior change. Behav. Sci. Policy 2016, 2, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, J.J.; Yoeli, E.; Rand, D.G. Don’t get it or don’t spread it: Comparing self-interested versus prosocial motivations for COVID-19 prevention behaviors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyighan, D.; Okwu, E. Social media for information dissemination in the digital era. RAY Int. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2024, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- BMSY. The Three-Year Action Plan for Improving National Health Literacy (2024–2027) Was Released. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/YptyqXcLvceBWHQ04fHRkw (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Zeng, F.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Hu, H. Douyin and Bilibili as sources of information on lung cancer in China through assessment and analysis of the content and quality. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilongjiang Traffic Radio, A Toothpaste to Solve a Variety of “Dental Problems”? Cold Acid Ling Live, Video Is Accused of Super Efficacy Propaganda. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/zK2yBWoLDKYdKtuPXtnj5Q (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Al-Dmour, H.; Masa’deh, R.; Salman, A.; Al-Dmour, R.; Abuhashesh, M. The role of mass media interventions on promoting public health knowledge and behavioral social change against COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221082125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiu, R. Memory Recognition and Recall in User Interfaces. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/recognition-and-recall/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Borah, P. The moderating role of political ideology: Need for cognition, media locus of control, misinformation efficacy, and misperceptions about COVID-19. Int. J. Commun. 2022, 16, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, A. Perceived Severity. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/constructs/perceived-severity#:~:text=Perceived%20severity%20(also%20called%20perceived,a%20pre%2Dexisting%20health%20problem (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Han, L.; Zhan, Y.; Li, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J. Associations between the perceived severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, cyberchondria, depression, anxiety, stress, and lockdown experience: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e31052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyeoku, E.K.; Talabi, F.O.; Oloyede, D.; Boluwatife, A.A.; Gever, V.C.; Ebere, I. Predicting COVID-19 health behaviour initiation, consistency, interruptions and discontinuation among social media users in Nigeria. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daab059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttikun, C.; Mahasuweerachai, P.; Bicksler, W.H. Environmental messaging, corporate values, online engagement and purchase behavior: A study of green communications among eco-friendly coffee retailers. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2025, 8, 1073–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, L.; Andrews, J.L. Are mental health awareness efforts contributing to the rise in reported mental health problems? A call to test the prevalence inflation hypothesis. New Ideas Psychol. 2023, 69, 101010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mya, S.; Aye, S.; Hlaing, W.A.; Hlaing, S.S.; Aung, T.; Lwin, S.M.M.; Ei, S.U.; Tun, T.; Lwin, K.S.; Win, H.H. Awareness, perceived risk and protective behaviours of Myanmar adults on COVID-19. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2020, 7, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Gautam, R.K.; Pham, L. The health belief model applied to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A systematic review. Vaccines 2022, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Jiang, H.; Wu, X.; Kong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Hu, D. Exploring users’ health behavior changes in online health communities: Heuristic-systematic perspective study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Gong, L.; Liu, H.; Kong, Y.; Wu, X.; Guo, Y.; Hu, D. Research on the influencing factors of users’ information processing in online health communities based on heuristic-systematic model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 966033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-B.; Yang, A.; Dou, K.; Wang, L.-X.; Zhang, M.-C.; Lin, X.-Q. Chinese public’s knowledge, perceived severity, and perceived controllability of COVID-19 and their associations with emotional and behavioural reactions, social participation, and precautionary behaviour: A national survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazione, S.; Perrault, E.; Pace, K. Impact of information exposure on perceived risk, efficacy, and preventative behaviors at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, B.; Richards, R.; Lally, P.; Rebar, A.; Thwaite, T.; Beeken, R.J. Breaking habits or breaking habitual behaviours? Old habits as a neglected factor in weight loss maintenance. Appetite 2021, 162, 105183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, C.; Vermeulen, J.; Cowan, B.R.; Beale, R. Digital behaviour change interventions to break and form habits. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. (TOCHI) 2018, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaver, L.; McGough, A.M.; Du, M.; Chang, W.; Chomitz, V.; Allen, J.D.; Attai, D.J.; Gualtieri, L.; Zhang, F.F. Self-reported changes and perceived barriers to healthy eating and physical activity among global breast cancer survivors: Results from an exploratory online novel survey. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 233–241.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arin, K.P.; Mazrekaj, D.; Thum, M. Ability of detecting and willingness to share fake news. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Dong, X. Factors influencing correction upon exposure to health misinformation on social media: The moderating role of active social media use. Online Inf. Rev. 2024, 48, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, F.M.; Oppong Asante, K.; Kugbey, N. Perceived seriousness mediates the influence of cervical cancer knowledge on screening practices among female university students in Ghana. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leister, T.S. Stick to the Meat You Know-The Role of Status Quo Bias and Moral Disengagement in Sustaining Meat Consumption. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg, S.; Bayazit, M.; Vakola, M.; Arciniega, L.; Armenakis, A.; Barkauskiene, R.; Bozionelos, N.; Fujimoto, Y.; González, L.; Han, J. Dispositional resistance to change: Measurement equivalence and the link to personal values across 17 nations. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Shen, F. Does fact-checking habit promote COVID-19 knowledge during the pandemic? Evidence from China. Public Health 2021, 196, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bas-Sarmiento, P.; Poza-Méndez, M.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, M.; González-Caballero, J.L.; Falcón Romero, M. Psychometric assessment of the European health literacy survey questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q16) for Arabic/French-speaking migrants in southern Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddourah, B.; Abu-Shaheen, A.K.; Al-Tannir, M. Quality of nursing work life and turnover intention among nurses of tertiary care hospitals in Riyadh: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, M. How online social support enhances individual resilience in the public health crisis: Testing a dual-process serial mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 158, 108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.; Hill, L.G.; Orrell-Valente, J.K. Media exposure, internalization of the thin ideal, and body dissatisfaction: Comparing Asian American and European American college females. Body Image 2011, 8, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Yoon, H.-J. Quality controlled YouTube content intervention for enhancing health literacy and health behavioural intention: A randomized controlled study. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241263691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. An Experimental Study of the Reduplication of Gradable Adjectives in Mandarin Chinese. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 8, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, I.; Ohs, J.; Park, T.; Hinsley, A. Interpersonal communication influence on health-protective behaviors amid the COVID-19 crisis. Health Commun. 2023, 38, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ji, L.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Yang, G.; Cui, T.; Shi, N.; Zhu, L.; Xiu, S.; Jin, H. Vaccination intention and behavior of the general public in China: Cross-sectional survey and moderated mediation model analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e34666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, I.; Ștefan, S.C.; Olariu, A.A.; Popa, Ș.C.; Popa, C.F. Modelling the COVID-19 pandemic effects on employees’ health and performance: A PLS-SEM mediation approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waqar, A.; Othman, I.; Radu, D.; Ali, Z.; Almujibah, H.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Khan, M.B. Modeling the relation between building information modeling and the success of construction projects: A structural-equation-modeling approach. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, M.A.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, S.B. The influence of sleep on job satisfaction: Examining a serial mediation model of psychological capital and burnout. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1149367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bai, D.; Song, P.; Zhang, J. Effects of physical health beliefs on college students’ physical exercise behavior intention: Mediating effects of exercise imagery. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.; Kim, S.-Y.; Suh, Y. Sample size requirements for simple and complex mediation models. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2022, 82, 76–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Ma, X. Combating health misinformation on social media through fact-checking: The effect of threat appraisal, coping appraisal, and empathy. Telemat. Inform. 2023, 84, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S. The roles of worry, social media information overload, and social media fatigue in hindering health fact-checking. Soc. Media Soc. 2022, 8, 20563051221113070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Predicting fact-checking health information before sharing among people with different levels of altruism: Based on the influence of presumed media influence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 2023, 1495–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, K.; Jeong, Y. Exploring Older Adults’ Views on Health Information Seeking: A Cognitive Load Perspective and Qualitative Approach. J. Korean Soc. Inf. Manag. 2020, 37, 177–202. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, F.M.; Holle, R.; Schwettmann, L.; Peters, A.; Laxy, M. Status quo bias and health behavior: Findings from a cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, M.; Felder, S. Can decision biases improve insurance outcomes? An experiment on status quo bias in health insurance choice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 2560–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangtammaruk, P. The effect of nutrition information, status quo bias, and loss aversion on the health of Thais and their consumption behaviour: A behavioural economic approach. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2020, 24, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. A revisit of fake news dataset with augmented fact-checking by chatgpt. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11870. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Xiong, X.; Xu, B. Attitudes and perceptions of Chinese oncologists towards artificial intelligence in healthcare: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Digit. Health 2024, 6, 1371302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R.H.; Gottfredson, N.C. Sample size considerations in prevention research applications of multilevel modeling and structural equation modeling. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stimulus | Main Content | Misinformation Theme | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shares a method for making a homemade solution for cleaning teeth, allowing you to avoid the cost of professional cleaning. | DIY remedy | 20 s |

| 2 | Promotes an opportunity to get full dental implant service at a very low price. | Cost-related deception | 37 s |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | 0.89 | ||||

| NFC | 0.13 ** | 0.87 | |||

| PS | 0.24 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.84 | ||

| RSQB | 0.13 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.85 | |

| FCI | 0.02 | 0.53 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.72 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR | |||||

| NFC | 0.15 | ||||

| PS | 0.27 | 0.31 | |||

| RSQB | 0.16 | 0.67 | 0.48 | ||

| FCI | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 0.72 |

| Variable | Item | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 243 | 53.8% |

| Male | 209 | 46.2% | |

| Education level | High school | 23 | 5.1% |

| Undergraduate | 318 | 70.4% | |

| Postgraduates | 111 | 24.6% | |

| Age | 18–23 years old | 292 | 64.6% |

| 24–28 years old | 106 | 23.5% | |

| 29–36 years old | 54 | 11.9% | |

| Monthly household income (CNY) | 1000–3999 | 119 | 26.3% |

| 4000–8999 | 99 | 21.9% | |

| 9000–13,999 | 131 | 29.0% | |

| ≥14,000 | 103 | 22.8% | |

| Total | 452 | 100% |

| Mediated Effects | Effect | P | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR → NFC →FCI | 0.10 | *** | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| MR → PS →FCI | 0.10 | *** | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| MR → NFC → RSQB → FCI | 0.03 | *** | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| MR → PS → RSQB → FCI | 0.10 | *** | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | MR is positively associated with Chinese college young adults’ NFC. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 2 | MR is positively associated with Chinese college young adults’ PS. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3 | NFC mediates the relationship between MR and Chinese young adults’ FCI. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 4 | PS mediates the relationship between MR and Chinese young adults’ FCI. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 5 | NFC and RSQB play a serial mediating role in the relationship between MR and Chinese young adults’ FCI. | Supported |

| Hypothesis 6 | PS and RSQB play a serial mediating role in the relationship between MR and Chinese young adults’ FCI. | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y. Unpacking Young Adults’ Fact-Checking Intent on Oral Health Misinformation: Parallel Mediating Roles of Need for Cognition and Perceived Seriousness—A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111354

Chung D, Zhang Y, Wang J, Meng Y. Unpacking Young Adults’ Fact-Checking Intent on Oral Health Misinformation: Parallel Mediating Roles of Need for Cognition and Perceived Seriousness—A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111354

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Donghwa, Yongjun Zhang, Jiaqi Wang, and Yanfang Meng. 2025. "Unpacking Young Adults’ Fact-Checking Intent on Oral Health Misinformation: Parallel Mediating Roles of Need for Cognition and Perceived Seriousness—A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111354

APA StyleChung, D., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., & Meng, Y. (2025). Unpacking Young Adults’ Fact-Checking Intent on Oral Health Misinformation: Parallel Mediating Roles of Need for Cognition and Perceived Seriousness—A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(11), 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111354